Coligny calendar

.jpg)

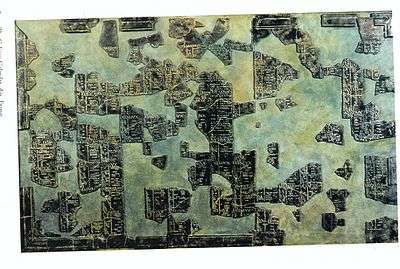

The Coligny calendar is a peg calendar (or parapegma[2]) made in Roman Gaul in ca. the 2nd century AD, giving a five-year cycle of a lunisolar calendar with intercalary months. It is the most important evidence for the reconstruction of an ancient Celtic calendar. It is written in Latin inscriptional capitals and is in the Gaulish language. The restored tablet contains sixteen vertical columns, with 62 months distributed over five years.

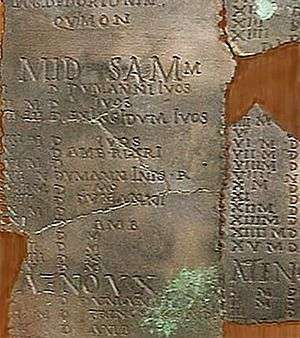

It was found in 1897 in France, in Coligny, Ain département (46°23′N 5°21′E / 46.383°N 5.350°E, near Lyon), along with the head of a bronze statue of a youthful male figure. It is now held at the Gallo-Roman Museum of Lyon. It was engraved on a bronze tablet, preserved in 73 fragments, that was originally 1.48 m wide by 0.9 m tall (5 ft wide by 3 1⁄2 ft tall).[3] Based on the style of lettering and the accompanying objects, it probably dates to the end of the 2nd century AD.[4][5]

A similar calendar found nearby at Villards d'Heria (46°25′N 5°44′E / 46.417°N 5.733°E) is preserved in only eight small fragments. It is now preserved in the Musée d'Archéologie du Jura at Lons-le-Saunier.

Reconstruction

The Continental Celtic calendar as reconstructed from the calendars of Coligny and Villards d'Heria was a lunisolar calendar, attempting to synchronize the solar year and the lunar month. The common lunar year contained 354 or 355 days.

The calendar year began with Samonios (samon is Gaulish for summer, Lambert p. 112). Le Contel and Verdier (1997) argue for a summer solstice start of the year. Monard (1999) argues for an autumn equinox start (by association with Irish Samhain).

The entry TRINOX[tion] SAMO[nii] SINDIV "three-nights of Samonios today") on the 17th of Samonios suggests that, like the Irish festival of Samhain, it lasted for three nights. The phrase *trinoxtion Samonii is comparable to a Gaulish festival mentioned in a 1st-century AD Latin inscription from Limoges, France, which mentions a "10 night festival (*decamnoctiacon) of (Apollo) Grannus" ( POSTVMVS DV[M]NORIGIS F(ILIVS) VERG(OBRETVS) AQVAM MARTIAM DECAMNOCTIACIS GRANNI D[E] S[VA] P[ECVNIA] D[EDIT])[6]

The solar year was approximated by the insertion of a 13th intercalary month every two and a half years. The additional months were intercalated before Samonios in the first year, and between Cutios and Giamonios in the third year. The name of the first intercalary month is not known with certainty, the text being fragmentary. In a suggestion first made by Schmidt (1979:198),the name of the first intercalary month is probably Quimonios, found in the final verse of the gnomic line at the end of the month, OX[.]ANTIA POC DEDOR TON IN QVIMON, emended to [TRICANTON] OX[OC]ANTIA PO(N)C(E) DEDOR TON IN(ON) QVIMON(IV) "Three hundred eighty and five are given this year through Quimonios" (Quimon- abbreviating the io-stem dative Quimoniu).[7] The name of the second intercalary month is reconstructed as Rantaranos or Bantaranos, based on the reading of the fifth line in the corresponding fragment. A gnomic verse pertaining to intercalation was taking up the first two lines, read as CIALLOS B(IS) SONNO CINGOS.[8] The term sonno cingos is interpreted as "sun's march" = "a year" by Delamarre (2003).

The months were divided into two halves, the beginning of the second half marked with the term atenoux or "renewal"[9] (cf. Old Irish athnugud "renewal"). The basic unit of the Celtic calendar was thus the fortnight or half-month, as is also suggested in traces in Celtic folklore. The first half was always 15 days, the second half either 14 or 15 days on alternate months (similar to Hindu calendars).

Months of 30 days were marked MAT, months of 29 days were marked ANM(AT). This has been read as "lucky" and "unlucky", respectively, based on comparison with Middle Welsh mad and anfad, but the meaning could here also be merely descriptive, "complete" and "incomplete".[10] There is no indication of any religious or ritual content.[11]

The Coligny calendar as reconstructed consisted of a of 16 columns and 4 rows, with two intercalary months given half a column (spanning two rows) each, resulting in a table of the 62 months of the five-year cycle, as follows (numbered 1–62, with the first three letters of their reconstructed names given for ease of reference; intercalary months are marked in yellow):

| Qui 1. | Riu 4. | Gia 8. | Aed 12. | Riu 16. | Gia 20. | Aed 24. | Riu 28. | Ran 32. | Equ 35. | Sam 39. | Ogr 43. | Equ 47. | Sam 51. | Ogr 55. | Equ 59. |

| Ana 5. | Sim 9. | Can 13. | Ana 17. | Sim 21. | Can 25. | Ana 29. | Ele 36. | Dum 40. | Qut 44. | Ele 48. | Dum 52. | Qut 56. | Ele 60. | ||

| Sam 2. | Ogr 6. | Equ 10. | Sam 14. | Ogr 18. | Equ 22. | Sam 26. | Ogr 30. | Gia 33. | Aed 37. | Riu 41. | Gia 45. | Aed 49. | Riu 53. | Gia 57. | Aed 61. |

| Dum 3. | Qut 7. | Ele 11. | Dum 15. | Out 19. | Ele 23. | Dum 27. | Out 31. | Sim 34. | Can 38. | Ana 42. | Sim 46. | Can 50. | Ana 54. | Sim 58. | Can 62. |

In spite of its fragmentary state, the calendar can be reconstructed with confidence due to its regular composition. An exception is the 9th month Equos, which in years 1 and 5 is a month of 30 days but in spite of this still marked ANM. MacNeill (1928) suggested that Equos in years 2 and 4 may have had only 28 days,[12] while Olmsted suggested 28 days in year 2 and 29 days in year 4.[13]

The following table gives the sequence of months in a five-year cycle, with the suggested length of each month according to Mac Neill and Olmsted:

| month name | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quimonios | 30 | - | - | - | - |

| 1. Samonios | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| 2. Dumannios | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 |

| 3. Riuros | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| 4. Anagantio | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 |

| 5. Ogronnios | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| 6. Qutios | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Rantaranos | - | - | 30 | - | - |

| 7. Giamonios | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 |

| 8. Semiuisonns | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| 9. Equos | 30 | 28 | 30 | 28/29 | 30 |

| 10. Elembiuios | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 |

| 11. Aedrinios | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| 12. Cantlos | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 |

| year length | 385 | 353 | 385 | 353 or 354 | 355 |

| total length | 1831 or 1832 days | ||||

The total of 1831 days is very close to the exact value of 62 × 29.530585 = 1830.90 days, keeping the calendar in relatively good agreement with the synodic month (with an error of one day in 50 years), but the aim of reconciling the lunar cycle with the tropical year is only met with poor accuracy, five tropical years corresponding to 5 × 365.24219052 = 1826.21 days (with an error of 4.79 days in five years, or close to one day per year).

As pointed out already by Ricci (1898), based on the mention of a 30-year cycle used by the Celts in Pliny's Naturalis historia (book 16), if one intercalary month is dropped every thirty years, the error is reduced to 30 – (6 × 4,79) = 1.27 days in a 30-year period (or a shift of the seasons by one day in about 20 to 21 years). This proposed omission of the intercalary month once in 30 years also improves the accuracy of the lunar calendar, assuming 371 lunations in 10,956 days, or an assumed synodic month of 371⁄10956 = 29.53010 days, resulting in an error of one day in 195 years.

Steinrücken (2012) has proposed that Pliny's statement that the Celtic month begins on the sixth day of the month[14] may be taken as evidence for the age of this system: assuming that the month was originally aligned with lunations, a shift of five days corresponds to a period of 975 years, suggesting a starting date in the 10th century BC.[15] Omsted (1992) in a similar argument proposes an origin around "850 ± 300 BC".[16]

In the Coligny calendar, there is a hole in the metal sheet for each day, intended for a peg marking the current date. The middle of each month is marked atenoux, interpreted as the term for the night of the full moon.[17]

There is an additional marker prinni loudin in 30-day months (MAT), at the first day of the first month (Samonios), the second day of the second 30-day month, and so on. The same system is used for 29-day months (ANMAT), with a marker prinni laget. In Olmsted's interpretation, prinni is translated "path, course", loudin and laget as "increasing" and "decreasing", respectively, in reference to the yearly path of the Sun, prinni loudin in Samonios marking winter solstice and prinni laget in Giamonios marking summer solstice.[18]

Sample month

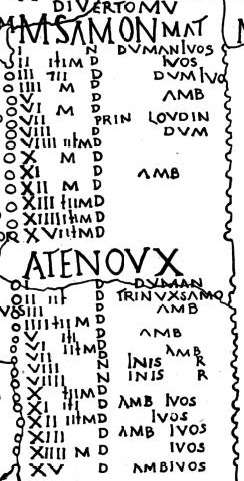

The following table shows the arrangement of a complete month (Samonios of year 2, with TRINVX(TION)SAMO(NII) marked on the 17th day). This is the only month out of 62 that has been preserved without any lacuna.[19]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Each month is divided into two half-months or "fortnights", divided by the word atenoux. Within each half-month, the arrangement is tabular, with the Roman numeral of the day of the half-month (with the hole for the peg marking the current day indicated as a circle). In the next column are occasional "trigrams" of the form +II, I+I or II+, and sometimes the letter M, of unknown significance. In a third column, each day is marked by the letter N or D (excepting days marked as prinni loudin or prinni laget). In the final column, days are marked with additional information, such as IVOS,[20] INIS R,[21] AMB (only found on odd days), among others. In the month Samonios depicted above, the 17th day is marked TRINVXSAMO, corresponding to TRINOSAM SINDIV in Samonios of year 1.

The name of the following month, DVM(AN), is mentioned several times (on days 1, 3, 8 and 16). Conversely, the following month marks days 1, 8, 16 and 17 with SAMON(I). This "exchanging of days" in odd months with the following, and in even months with the preceding month is also found in other parts of the calendar.

List of months

The names of the twelve months as recorded are 1. samon-, 2. dumann-, 3. riuros, 4. anagantio-, 5. ogronn-, 6. cutios, 7. giamoni-, 8. simiuisonna-, 9. equo, 10. elembiu-, 11. edrini-/aedrini-, 12. cantlos. Most of these names are without evident etymology, with the notable exceptions of samon- and giamoni-, being the stems of the words for "summer" and "winter", respectively, besides equos and cantlos, sometimes associated with Celtic words for "horse" and "song", respectively, and ogronn-, interpreted as a word for "cold" by Birkhan (1997).[22]

| month name | days | etymology | interpretation[23] | notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Samonios | 30 | "[month] belonging to summer".[24] | June–July | trinoxtion Samonii on 17th Samonios presumably marks the full moon closest to midsummer. |

| 2. Dumannios | 29 | tentatively compared with Latin fūmus "smoke" ("month of fumigation"?).[25] | July–August | |

| 3. Riuros | 30 | tentatively compared with Old Irish remor "stout, thick, fat", Welsh rhef "thick, stout, great, large"[26] | August–September | |

| 4. Anagantio | 29 | unknown (perhaps "non-travelling"[27]) | September–October | |

| 5. Ogronnios | 30 | "cold month"[28] | October–November | |

| 6. Cutios | 30 | unknown[29] | November–December | |

| 7. Giamonios | 29 | "[month] belonging to winter"[30] | December–January | 17th Giamonios, the day opposite trinoxtion Samonii (i.e. the full moon closest to midwinter) is marked NSDS |

| 8. Semiuisonns | 30 | unknown[31] | January–February | |

| 9. Equos | 30/28/29 | unknown[32] | February–March | |

| 10. Elembiuios | 29 | compared to the word for "deer" and the Attic Έλαφηβολιών "month of the deer-hunt".[33] | March–April | |

| 11. Aedrinios | 30 | compared with Old Irish aed "fire", "heat"[34] | April–May | |

| 12. Cantlos | 29 | compared with Welsh cathl, Old Irish cétal "song". | May–June | 15th Cantlos is marked TIOCOBREXT(IO)[35] |

The names of the twelve regular months can be reconstructed with some certainty in spite of the fragmentary state of the calendar, as each of them was repeated five times. The two intercalary months occur only once each, and their names are consequently reconstructed with much less certainty. The name Quimonios is taken from the reading QVIMON at the very end of the first segment, and the reconstucton of either *Rantaranos or *Bantaranos is based on the reading [.]ANTARAN in the fifth line of the 32nd segment. Olmsted (1992) gives a tentative explanation of *Rantaranos as "the count in between".[36]

See also

References

- ↑ The arrangement by de Ricci misplaces four fragments according to Duval and Pinault (1986).

- ↑ Lehoux, D. R. Parapegmata: or Astrology, Weather, and Calendars in the Ancient World. PhD Dissertation, University of Toronto, 2000.

- ↑ Lambert p. 111. Coligny Calendar

- ↑ Duval, P.M. and Pinault, G., Recueil des inscriptions gauloises, Tome 3: Les Calendriers (Coligny, Villards d'Heria), CNRS, Paris, 1986, pp. 35-37.

- ↑ Lambert, Pierre-Yves, La langue gauloise, Editions Errance, 2nd edition, Paris, 2003, p.111

- ↑ Lejeune, Michel, "Notes d'etymologie gauloise" ("XI. Les 'Dix Nuits' de Grannos"), Études Celtiques, XXXI, 1995, 91-97.

- ↑ Olmsted, Garrett, "The Use of Ordinal Numerals on the Gaulish Coligny Calendar", The Journal of Indo-European Studies 16 (1988), p. 296.

- ↑ Dottin (1920:192); Lambert p. 116.

- ↑ The interpretation of atenoux as "returning night" is improbable (Delamarre p.58) and "renewing" would seem more probable; thus the month would start at new moon and atenoux would indicate the renewal, ie the full moon.

- ↑ Bernhard Maier: Lexikon der keltischen Religion und Kultur. S. 81 f.

- ↑ Bernhard Maier: Die Religion der Kelten. Götter, Mythen, Weltbild, Stuttgart, 1994, 60f.

- ↑ Eóin MacNeill: On the Notation and Chronology of the Calendar of Coligny, Eriu X, 1928, 1-67.

- ↑ Garrett Olmsted: The Gaulish calendar (1992), ISBN 3-7749-2530-5. Garrett Olmsted: A Definitive Reconstructed Text of the Coligny Calendar (2001), ISBN 9780941694780

- ↑ Pliny, NH 16.95: "The mistletoe, however, is but rarely found upon the oak; and when found, is gathered with rites replete with religious awe. This is done more particularly on the sixth day of the moon, the day which is the beginning of their months and years, as also of their ages, which, with them, are but thirty years. This day they select because the moon, though not yet in the middle of her course, has already considerable power and influence; and they call her by a name which signifies, in their language, the all-healing." Bostock, John, Henry Thomas Riley (eds) (1855). Pliny the Elder, The Natural History Book 16, "the natural history of the forest trees". English translation (available online). Original Latin (also available). The Latin text of the specific passage is est autem id rarum admodum inventu et repertum magna religione petitur et ante omnia sexta luna, quae principia mensum annorumque his facit et saeculi post tricesimum annum, quia iam virium abunde habeat nec sit sui dimidia.

- ↑ Burkard Steinrücken, Lunisolarkalender und Kalenderzahlen am Beispiel des Kalenders von Coligny (2012), pp. 7, 19.

- ↑ "Most probably the 30-year calendar developed in a purely preliterate tradition as the displacement of the Irish quarter festivals suggests in projecting an origin around 850 ± 300 BC [...] If so, the calendar must have been preserved from generation to generation by a body of supportive gnomic verse." Olmsted (1992:107).

- ↑ Garrett Olmsted: The Gaulish calendar, Bonn, 1992, p. 172.

- ↑ Garrett Olmsted: The Gaulish calendar, Bonn, 1992, pp. 76, 176-177

- ↑ Dottin (1920:182)

- ↑ Series of days labelled IVOS occur in sequence, marking a period of eight or nine days running from the end of one month to the beginning of the next (mostly 26th to 4th), often interpreted as "festival days", apparently of the nature of a "movable feast" as the IVOS days do not occur in the same months of different years in the five-year cycle. "At the beginning of Elembiv in year 2 there are five IVOS days, whereas other months begin with only three or four. The unusually long run at the beignning of Elembiv year 2 appears to be making up for a lost IVOS day at the end of Equos." Sacha Stern, Calendars in Antiquity, Oxford University Press, 2012, p. 305. The word ivos has long been associated with the Celtic word for "yew" (Rhys (1910:52), c.f. Ivo, īwaz) but according to a suggestion by Zavaroni (2007:97) means "(con)junction".

- ↑ INIS R always follows N in the preceding column. Annuaire 1966-1967 , École Pratique des Hautes Études, Librairie Droz, p. 220.

- ↑ Helmut Birkhan: Kelten. Versuch einer Gesamtdarstellung ihrer Kultur. (1997), 786ff.

- ↑ Following the interpretation of MacNeill (1926), who places summer solstice in Samonios. This is also endorsed by Le Contel and Verdier (1997). A minority view is expressed by Monard (1999), who prefers to place the beginning of the year at autumnal equinox, resulting in a shift of a quarter of a year in the interpretation of the seasonal placements of the months. The mainstream view has the additional virtue of agreeing with several etymologizations, placing Riuros the "fat month" near harvest, Ogronnios the "cold month" in October/November, and agreement of both Elembiuios with Attic Έλαφηβολιών and Cutios with Locrian Κοούτιος.

- ↑ Likely an n-stem derivative (with a suffix of appurtenance, -io-) of the Common Celtic root *samo- "summer", found in Old Irish sam, Welsh haf. Cf. Old Irish Samain "(festival of the) First of November", "All-Hallows/All-Saints day" and Mithem, Mithemain "Mid-summer, month of June", Middle Welsh Meheuin "June" (both from Common Celtic *Medi[o]-samVn [V="vowel", likely -o- or -u-], as well as Old Irish Cétamuin "Month of May", "First of May", "May Day" (alternate name for Beltain), Welsh Cyntefin "month of May" (both from Common Celtic *kintu-samonis "beginning of Summer" Schrijver, Peter, Studies in British Celtic Historical Phonology, Rodopi, 1995, p. 265-266)

- ↑ Sanskrit dhūmah "smoke", Greek θύμος (thūmos) "soul, life, passion; anger, wrath" (also θύμιάω [thūmiaoo] "to burn, as incense", θύμα [thūma] "sacrificial offering"). Delamarre (2003)

- ↑ in which case, the original form may have been *Remros, with later shift of -e- to -i- [compare the alternation between Semi- and Simi- in Semuisonna] and lenition of internal -m-. Some scholars alternately suggest a connection with Old Irish réud, Welsh rhew "cold".

- ↑ interpreted as containing the negative prefix *an- and an agentive noun *agant- based on the root *ag- "to go, to conduct, to lead". Cf. Old Irish ag "to go, do, conduct", Welsh agit "goes", perhaps yielding a sense of ""month in which one does not travel".

- ↑ Birkhan (1997). An n-stem derivative of the Common Celtic root *ougros "cold". Cf. Old Irish úar, Welsh oer. The root *oug- is further compared to Armenian oyc "cold", Lithanian auksts "cold", and Latin a(u)ctumnus "autumn" by Delamarre (2003).

- ↑ Delamarre (2003) compares guti "to invoke" (in gutuater, a class of priests of the Carnutes). Sometimes also compared with Κοούτιος (Kooutios) in the Locrian calendar from Chaleion. Locrian Kooutios is equated to the third month of the Federal calendar, which is in turn equated with Delphian Apellaios, corresponding to November. Alan Edouard Samuel, Greek and Roman Chronology: Calendars and Years in Classical Antiquity, Volume 1, Part 7, C.H.Beck, 1972, p. 77.

- ↑ an n-stem derivative (suffix of appurtenance -io-) derived from the Common Celtic root *giįamo- "winter". Cf. Welsh gaeaf, Breton goañv, Old Irish gaim "winter", Gamain "month of November" (Delamarre 2003).

- ↑ Perhaps Common Celtic *sēmi- "half" plus *ues- "Spring(time)" or a compound containing a feminine form of the word for "sun", *sonna

- ↑ The often-cited comparison to the word for "horse" has limited acceptance because the Gaulish word for "horse" is epos, not equos (c.f. Epona). Those scholars who still retain the comparison are reduced to assuming "Q-Celtic dialectal features".

- ↑ cognate with Welsh elain and Old Irish elit, "doe, hind; young deer". The Attic calendar has a "Month of the Deer-hunt", Έλαφηβολιών (Elaphebolion), equivalent to March–April. Proto-Indo-European root *elen-bho- "deer", which gave us English lamb and the Greek έλαφος (elaphos).

- ↑ Greek αἰθήρ (aithēr) "bright sky, upper air, ether", ultimately from the Proto-Indo-European root *aidh- which also gave us Latin aestas "summer" (Delamarre 2003).

- ↑ Delamarre (2003) proposes derivation from *tio-com-rextu- "day of justice", i.e. "doomsday, court day". Recorded three times for 15th Cantlos, besides for 7th Semiuisonns (year 4), 8th Elembiuios (year 3) and 7th Giamonios (year 3).

- ↑ Olmsted (1992:200). Only part of the first letter of [.]ANTARAN remains visible, it may be either R, B or S.

Bibliography

- Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental. 2nd edition, Paris, Editions Errance. ISBN 2-87772-237-6.

- Dottin, Georges, La langue gauloise : grammaire, textes et glossaire (1920) no. 53, pp. 172–207.

- Duval, Paul-Marie and Pinault, Georges (eds) (1986). Recueil des inscriptions gauloises (R.I.G.), Vol. 3: Les calendriers de Coligny (73 fragments) et Villards d'Heria (8 fragments). Paris, Editions du CNRS.

- Hitz, Hans-Rudolf (1991). Der gallo-lateinische Mond- und Sonnen-Kalender von Coligny.

- Joyce, P.W. (2000). "Old Celtic Romances". The pursuit of the Giolla Dacker and his horse. Wordsworth Editions Limited, London.

- Laine-Kerjean, C. (1943). "Le calendrier celtique". Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie, 23, pp. 249–84.

- Lambert, Pierre-Yves (2003). La langue gauloise. Paris, Editions Errance. 2nd edition. ISBN 2-87772-224-4. Chapter 9 is titled "Un calandrier gaulois".

- Le Contel, Jean-Michel and Verdier, Paul (1997). Un calendrier celtique: le calendrier gaulois de Coligny. Paris, Editions Errance. ISBN 2-87772-136-1

- McCluskey, Stephen C. (1990). "The Solar Year in the Calendar of Coligny". Études Celtiques, 27, pp. 163–74.

- Mac Neill, Eóin (1928). "On the notation and chronology of the Calendar of Coligny". Ériu, X, pp. 1–67.

- Monard, Joseph (1996). About the Coligny Calendar. privately published monograph.

- Monard, Joseph (1996). Découpage saisonnier de l'année celtique. privately published monograph.

- Monard, Joseph (1999). Histoire du calendrier gaulois : le calendrier de Coligny. Paris, Burillier. ISBN 2-912616-01-8

- Olmsted, Garrett (1992). The Gaulish calendar: a reconstruction from the bronze fragments from Coligny, with an analysis of its function as a highly accurate lunar-solar predictor, as well as an explanation of its terminology and development. Bonn: R. Habelt. ISBN 3-7749-2530-5

- Parisot, Jean-Paul (1985). "Les phases de la Lune et les saisons dans le calendrier de Coligny". Études indo-européennes, 13, pp. 1–18.

- Pinault, J. (1951). "Notes sur le vocabulaire gaulois, I. Les noms des mois du calendrier de Coligny". Ogam, XIII, pp. 143–154

- Rhys, John (1909). "The Coligny Calendar". Proceedings of the British Academy, 4, pp. 207–318.

- Thurneysen, Rudolf (1899). "Der Kalender von Coligny". Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie, 2, pp. 523–544

- Zavaroni, Adolfo (2007). On the structure and terminology of the Gaulish calendar, British Archaeological Reports British Series.

External links

- The Coligny Tablet (roman-britain.org)

- Bonsing, John (2007, 2011). The Celtic Calendar (caeraustralis.com.au).