Costoboci

.svg.png)

The Costoboci (/ˌkɒstəˈboʊsaɪ/; Latin: Costoboci, Costobocae, Castabocae, Coisstoboci, Ancient Greek: Κοστωβῶκοι, Κοστουβῶκοι or Κοιστοβῶκοι[1]) were an ancient people located, during the Roman imperial era, between the Carpathian Mountains and the river Dniester. During the Marcomannic Wars the Costoboci invaded the Roman empire in AD 170 or 171, pillaging its Balkan provinces as far as central Greece, until they were driven out by the Romans. Shortly afterwards, the Costoboci's territory was invaded and occupied by Vandal Hasdingi and the Costoboci disappeared from surviving historical sources, except for a mention by the late Roman Ammianus Marcellinus, writing around AD 400.

Name etymology

The name of the tribe is attested in a variety of spellings in Latin: Costoboci, Costobocae, Castaboci, Castabocae, Coisstoboci and in Ancient Greek: Κοστωβῶκοι, Κοστουβῶκοι, Κοιστοβῶκοι.[2][3]

According to Ion I. Russu, this is a Thracian compound name meaning "the shining ones".[4] The first element is the perfect passive participle Cos-to-, derived from the Proto-Indo-European root kʷek̂-, kʷōk̂- "to seem, see, show", and the second element is derived from the Proto-Indo-European root bhā-, bhō- "to shine", extended by the suffix -k-.[3] Ivan Duridanov considered it a Dacian name with unclear etymology.[5]

Some scholars argue that "Costoboci" has a Celtic etymology.[6]

N.B. Georgiev considers all etymologies based on Indo-European root-words (so-called Wurzeletymologien) to be "devoid of scientific value":[7] the root-words themselves are reconstructions, are necessarily incomplete and can have multiple descendants in several IE languages. In this case, the name Costoboci could mean "the shining ones" in languages other than Thracian (e.g. in Iranic or Celtic languages) or it could have a different root(s) than the ones surmised by Russu.

Territory

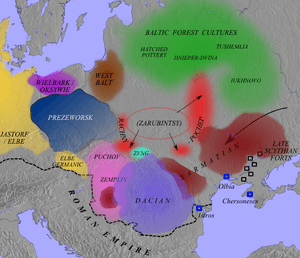

Mainstream modern scholarship locates this tribe to the north or north-east of Roman Dacia.[8][9][10] Some scholars considered that the earliest known mention of this tribe is in the Natural History of Pliny the Elder, published c. AD 77, as a Sarmatian tribe named the Cotobacchi living in the lower Don valley.[11][12][13][14] Other scholars have challenged this identification and have recognised the "Cotobacchi" as a distinct tribe.[8][15][16][17]

Ammianus Marcellinus, writing c. 400, locates the Costoboci between the Dniester and Danube rivers,[8][18] probably to the north-east of the former Roman province of Dacia.[19] In his Geographia (published between 135 and 143 AD),[20] the Greek geographer Ptolemy seems to indicate that the Costoboci inhabited north-western [21] or north-eastern Dacia.[8] In addition, some scholars identify the people called Transmontanoi (literally: "people beyond the mountains") by Ptolemy, located to the north of the Carpathians, as Dacian Costoboci.[22][23][12]

Material culture

Some scholars associate the Costoboci with the Lipiţa culture.[25][26] However Roger Batty, reluctant to correlate material culture with group identity, argues that Lipiţa culture belonged either to a subgroup of the Costoboci or to some population they ruled over.[27] This culture developed on the northern side of the Carpathians in the Upper Dniester and Prut basins in the Late La Tène period.[28][29]

The bearers of this culture had a sedentary lifestyle and practiced agriculture, cattle-breeding, iron-working and pottery.[28] The settlements were not fortified and contained sunken floored buildings, surface buildings, storage pits, hearths, ovens and kilns.[28] There are numerous pottery finds of various types, both wheel and hand-made, with similarities in shape and decoration to the pottery of the pre-Roman Dacia.[28] The pottery finds of the northern Lipiţa sites in the upper Zolota Lypa basin are similar to that of the Zarubintsy culture.[26]The cemeteries were found close to settlements. The predominant funeral rite was cremation, with urns containing ashes buried in plain graves, but several inhumation graves were also excavated.[28]

Onomastics

A Latin-language funerary inscription found in Rome, believed to date from the 2nd century AD, was dedicated to Zia or Ziais the Dacian, the daughter of Tiatus and the wife of Pieporus, a king of the Costoboci. The monument was set up by Natoporus and Drigisa, Zia's grandsons.[30][31][32] The inscription was first published by the Italian scholar Mariangelus Accursius in the 16th century, but it is now lost.[31][15]

Inscription

D(is) M(anibus)

ZIAI

TIATI FIL(iae)

DACAE. UXORI

PIEPORI. REGIS

COISSTOBOCENSIS

NATOPORUS ET

DRIGISA AVIAE

CARISS(imae) B(ene) M(erenti) FECER(unt)

Translation

"To the Spirits of the Dead. (Dedicated) to ZIA(IS) the Dacian, Daughter of TIATUS, Wife of PIEPORUS, Costobocan king. NATOPORUS and DRIGISA made (this memorial) for their most dear, well-deserving grandmother."

Name analysis

- Drigisa: a Thracian[33][34] or Dacian[35][36][37][38] name. It is considered a variant with the infix -l- of the name Drigis(s)a,[33][36][38] the name of the Roman veteran Aurelius Drigisa from Moesia Inferior and of the legionary Titus Aurelius Drigissa from Moesia Superior. The final element -gis(s)a is frequent in Dacian onomastics.[37]

- Natoporus: a Thracian[39][40] or Dacian[41][36][42][43] name. A soldier Natopor is known from several ostraca found at Mons Claudianus in eastern Egypt.[42][43] A Roman military diploma was issued in 127 in Mauretania Caesariensis for a Dacian soldier and his two children, a son Nattoporis and a daughter Duccidava.[42][43] It is a name ending in -por, a frequent Thracian and Dacian onomastic element.[44][45][46][47] On a military diploma issued in 127 in Germania Inferior, a Dacian soldier's father is named Natusis, a name formed with the same first element nat- and a suffix -zi-/-si-.[42][43]

- Pieporus: a Thracian[48][49] or Dacian[44][36][47] name. It is a name ending in -por, a frequent Thracian and Dacian onomastic element.[44][45][46][47]

- Tiatus: a Thracian[50][51] or Dacian[52][53][54][47] name. Tiatus is maybe a name starting in thia-, typical for Dacians.[55][56] A name Tiato is attested on a fragmentary dipinto found at Maximianon, a Roman fort in eastern Egypt.[54]

- Zia or Ziais: a Thracian[57][58] or Dacian[59][53][47] name. Zia is a female name attested in Moesia Inferior.[58][59][47]

Ethnolinguistic affiliation

The ethnic and linguistic affiliation of the Costoboci is uncertain due to lack of evidence.[60] The mainstream view is that they were a Dacian tribe, among the so-called "Free Dacians" not subjected to Roman rule.[61][62][63] However some scholars suggested they were Thracian, Sarmatian,[64][13] Slavic,[65] Germanic,[66] Celtic, or Dacian with a Celtic superstratum.[67]

The evidence adduced in support of the main ethnic hypotheses may be summarised as follows:

Dacian

- Onomastics: The family of a Costobocan king called Pieporus (2nd century) had names considered by some scholars to be of Dacian origin .

- The rubric Dacpetoporiani on the Tabula Peutingeriana has been interpreted by some scholars as an elision of "Daci Petoporiani" meaning the "Dacians of King Petoporus".[48][68][69] Schütte argued Petoporus is one and the same as Pieporus, the king of the Costoboci.[70]

- Archaeology: The Costoboci have been linked, on the basis of their geographical location, with the Lipitsa culture.[71][72][73] This culture's features, especially its pottery styles and burial customs, have been identified as Dacian by some scholars,[74][75] leading to the conclusion that the Costoboci were an ethnic-Dacian tribe.[76]

- Name etymology: According to Schütte, the Dacian element -bokoi is also occurring in the name of another Dacian tribe, the Sabokoi.[77] However, Batty argues that the Lipitsa culture is a poor fit for the Costoboci, not least because it appears to have disappeared during the 1st century BC, long before the period AD 100-200 when they are attested in and around Dacia by surviving historical documents.[78]

Thracian

- Onomastics: Some scholars consider the names of Pieporus and of his grandsons to be Thracian (see Onomastics, above).

- Archaeology: According to Jazdewski, in the early Roman period, on the Upper Dniestr, the features of the Lipitsa culture indicate ethnic Thracians under strong Celtic cultural influence, or who had simply absorbed Celtic ethnic components.[79]

- The fact that queen Zia is specifically characterised as "Dacian" may indicate that Pieporus and the Costoboci were not themselves Dacians.

Celtic

- The name Costoboci is considered by some scholars to be of Celtic etymology. In particular, they see the first element of their name as a corruption of coto-, a Celtic root meaning "old" or "crooked" (cf. Cotini, an eastern Celtic tribe in the same Carpathian region; Cottius, a king of the Celtic Taurini in the western Alps. One Pliny manuscript variant of the name Costoboci is Cotoboci). However, Faliyeyev argues that while possible, a Celtic derivation is less likely than an "autochthonous" one.[80]

- During the period 400-200 BC, Transylvania and Bessarabia saw intensive Celtic settlement, as evidenced by heavy concentrations of La Tène-type cemeteries.[81] Central Transylvania appears to have become a Celtic enclave or unitary kingdom, according to Batty.[82] Ptolemy lists 3 tribes as present in Transylvania: (west to east): the Taurisci, Anartes and Costoboci.[83] The first two are generally considered by scholars to be of Celtic origin.

- The Lipitsa culture displays numerous Celtic features.[84][79]

Scytho-Sarmatian

According to some scholars, the Costoboci were not a sedentary group at all, but a semi-nomadic steppe horse-based culture of Scytho-Sarmatian character. This hypothesis was originally proposed by the eminent 19th-century German classical scholar Theodor Mommsen.[85]

- The tribe called Cotobacchi (or Cotoboci or other manuscript variants) in a list of Sarmatian tribes in Pliny's Naturalis Historia[86] is considered by some scholars to refer to the Costoboci.[11][12][13][14] However, Russu and other scholars consider the Cotobacchi to be a distinct group, unconnected to the Costoboci.[15][87]

- The statement by Ammianus Marcellinus (ca, AD 400), that a region of the north Pontic steppes was inhabited by "the European Alans, the Costobocae and innumerable Scythian tribes".[88] According to some scholars, the region referred to is the entire steppe between the Danube and the river Don and the passage identifies the Costobocae as an Iranic steppe-nomadic people.[89][11][13][14] However, other scholars argue that the region referred to is much smaller, that between the Danube and Dniester.[8][18]

- The presence, throughout the region identified by ancient geographers as inhabited by the Costoboci (SW Ukraine, northern Moldavia and Bessarabia), interspersed among the sites of sedentary cremation cultures such as Lipitsa, of distinct Sarmatian-style inhumation cemeteries dating from the 1st and 2nd centuries AD.[90]

- An inscription found in the Sanctuary of the Mysteries at Eleusis in Greece, which is believed to have been carved by priests after this temple was sacked by the Costoboci during their invasion of 170/1. The inscription refers to the "crimes of the Sarmatians". Some scholars argue that this proves the Costoboci were Sarmatians.[91][92] However, other scholars suggest that the name of the Sarmatians was used as an umbrella term for raiders crossing the lower Danube,[61][93] or that it attests a joint invasion by Costoboci and Sarmatians.[94][95]

Conflict with Rome

During the rule of Marcus Aurelius, the Roman Empire fought the Marcomannic Wars, a vast and protracted struggle against Marcomanni, Quadi, and other tribes along the middle Danube. The Costoboci also joined the anti-Roman coalition at some stage.[97][95]

The invasion of 170/1

In AD 167 the Roman legion V Macedonica, returning from the Parthian War, moved its headquarters from Troesmis in Moesia Inferior to Potaissa in Dacia Porolissensis,[98][99] to defend the Dacian provinces against the Marcomannic attacks.[100] Other auxiliary units from Moesia Inferior participated in the middle Danube campaigns, leaving the lower Danube frontier defenses weakened.[100] Taking the opportunity,[100] in 170[101][94][102] or 171,[94][103] the Costoboci invaded Roman territory.[95] Meeting little opposition, they swept through and raided the provinces of Moesia Inferior, Moesia Superior, Thracia, Macedonia and Achaea.[60][95][104]

Northern Balkans

Crossing the Danube, the Costoboci burnt down a district of Histria which was thus abandoned.[105][106] Their attacks also affected Callatis and the walls of the city required reparations.[107][105] Two funerary inscriptions discovered at Tropaeum Traiani in Moesia Inferior commemorate Romans killed during the attacks: Lucius Fufidius Iulianus, a decurion and duumvir of the city and a man named Daizus, son of Comozous.[105] A vexillatio made of detachments of the legions I Italica and V Macedonica was deployed at Tropaeum in this period, perhaps to defend against these attacks.[108][100] The raiders then moved west reaching Dardania.[106] A tombstone found at Scupi in Moesia Superior was dedicated to Timonius Dassus, a decurion from the Roman auxiliary cohort II Aurelia Dardanorum, who fell in combat against the Costoboci.[109][106] Their offensive continued southwards, through Macedonia into Greece.[106]

Greece

In his description of the city of Elateia in central Greece, the contemporaneous travel-writer Pausanias mentioned an incident involving the local resistance against the Costoboci:[110]

An army of bandits, called the Costobocs, who overran Greece in my day, visited among other cities Elateia. Whereupon a certain Mnesibulus gathered round him a company of men and put to the sword many of the barbarians, but he himself fell in the fighting. This Mnesibulus won several prizes for running, among which were prizes for the foot-race, and for the double race with shield, at the two hundred and thirty-fifth Olympic festival. In Runner Street at Elateia there stands a bronze statue of Mnesibulus.

Pausanias, Description of Greece, X, 34, 5.[111]

Thereafter, the barbarians reached Athens where they sacked the famous shrine of the Mysteries at Eleusis.[112][94][104][113] In May[104] or June[110] 171, the orator Aelius Aristides delivered a public speech in Smyrna, lamenting the limited damage recently inflicted to the sacred site.[114][94][104][110] damage was limited.[115] Three local inscriptions praise an Eleusinian priest for saving the ritual's secrets.[116][117]

Even though much of the invasion force was spent, the local resistance was insufficient and the procurator Lucius Iulius Vehilius Gratus Iulianus was sent to Greece with a vexillatio to clear out the remnants of the invaders.[118][119][94][120] The Costoboci were thus defeated.[121][115]

Dacia

In the same period the Costoboci may have attacked Dacia. A bronze hand dedicated to Jupiter Dolichenus by a soldier from a cohort stationed in Dacia was found at Myszków in Western Ukraine. It has been suggested that this may have been loot from a Costobocan raid.[122][123][124] Some scholars suggest that it was during this turbulent period that members of King Pieporus' family were sent to Rome as hostages.[125][126][124][32]

The coming of the Vandals

Soon after AD 170,[127] the Vandal Astingi, under their kings, Raus and Raptus, reached the northern borders of Roman Dacia and offered the Romans their alliance in return for subsidies and land. Sextus Cornelius Clemens, the governor of the province, refused their demands, but he encouraged them to attack the troublesome Costoboci while offering protection for their women and children.[128][121][129][130] The Astingi occupied the territory of the Costoboci but they were soon attacked by another Vandal tribe, the Lacringi.[129][130][127] Both Astingi and Lacringi eventually became Roman allies, allowing the Romans to focus on the middle Danube in the Marcomannic wars.[129][130] Scholars variously suggest that the remnants of this tribe were subdued by the Vandals[73][127] or fled and sought refuge in the neighbouring territories of the Carpi[73][131] or in the Roman province of Dacia.[132]

See also

Citations

- ↑ Frazer 1898, p. 430

- ↑ Frazer 1898, p. 430.

- 1 2 Russu 1969, p. 116.

- ↑ Russu 1969, p. 98.

- ↑ Duridanov 1995, p. 836.

- ↑ Faliyeyev (2007) Entry: "Costoboci"

- ↑ Georgiev 1977, p. 271.

- 1 2 3 4 5 von Premerstein 1912, p. 146.

- ↑ Birley 2000, pp. 165,167.

- ↑ Talbert 2000, map 22.

- 1 2 3 Frazer 1898, pp. 429-430.

- 1 2 3 von Premerstein 1912, p. 145.

- 1 2 3 4 Ormerod 1997, p. 259.

- 1 2 3 Batty 2008, p. 374.

- 1 2 3 Russu 1959, p. 346.

- ↑ Talbert 2000, pp. 336,1209.

- ↑ Talbert 2000, maps 22,84.

- 1 2 Den Boeft et al. 1995, p. 105.

- ↑ Den Boeft et al. 1995, p. 138.

- ↑ Maenchen-Helfen Otto J. (1973) 448

- ↑ Frazer 1898, p. 429.

- ↑ Opreanu 1994, p. 197.

- ↑ Schütte 1917, pp. 100-101.

- ↑ Shchukin 1989, p. 285.

- ↑ Bichir 1980, p. 445.

- 1 2 Shchukin 1989, p. 285,306.

- ↑ Batty 2008, p. 375.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bichir 1980, p. 446.

- ↑ Mikołajczyk 1984, p. 62.

- 1 2 Muratori 1740, p. 1039.

- 1 2 3 Dessau 1892, p. 191.

- 1 2 Petersen & Wachtel 1998, p. 161.

- 1 2 Tomaschek 1980b, p. 35.

- ↑ Detschew 1957, pp. 157-158.

- ↑ Alföldi 1944, pp. 35,47-48.

- 1 2 3 4 Georgiev 1983, p. 1212.

- 1 2 Dana 2003, p. 174.

- 1 2 Dana 2006, p. 119.

- ↑ Tomaschek 1980b, p. 27.

- ↑ Detschew 1957, p. 328.

- ↑ Alföldi 1944, pp. 36,48.

- 1 2 3 4 Dana 2003, p. 178.

- 1 2 3 4 Dana 2006, pp. 118-119.

- 1 2 3 Alföldi 1944, pp. 36,49.

- 1 2 Georgiev 1983, p. 1200.

- 1 2 Dana 2003, pp. 179-181.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dana 2006, p. 118.

- 1 2 Tomaschek 1980b, p. 20.

- ↑ Detschew 1957, p. 366.

- ↑ Tomaschek 1980b, p. 36.

- ↑ Detschew 1957, p. 503.

- ↑ Alföldi 1944, pp. 37,50.

- 1 2 Georgiev 1983, p. 1212.

- 1 2 Dana 2003, p. 180.

- ↑ Dana 2003, pp. 179-180.

- ↑ Dana 2006, pp. 109-110,118.

- ↑ Tomaschek 1980b, p. 40.

- 1 2 Detschew 1957, p. 186.

- 1 2 Alföldi 1944, pp. 37,51.

- 1 2 Birley 2000, p. 165.

- 1 2 von Premerstein 1912, p. 147.

- ↑ Batty 2008, p. 22.

- ↑ Heather 2010, p. 131.

- ↑ Frazer 1898, p. 535.

- ↑ Müllenhoff 1887, pp. 84–87.

- ↑ Musset 1994, pp. 52,59.

- ↑ Nandris 1976, p. 729.

- ↑ Detschew 1957, p. 365.

- ↑ Dana 2003, p. 179.

- ↑ Schütte 1917, p. 82.

- ↑ Shchukin 1989, p. 306.

- ↑ Macrea 1970, p. 1039.

- 1 2 3 Bichir 1976, p. 161.

- ↑ Kazanski, Sharov & Shchukin 2006, p. 20.

- ↑ Shchukin 1989, p. 280.

- ↑ Bichir 1976, p. 164.

- ↑ Schütte 1917, p. 99.

- ↑ Batty (2008) 375

- 1 2 Jazdewski 1948, p. 76.

- ↑ Faliyeyev (2007) Entry on Costoboci

- ↑ Philips Atlas of the Celts, p. 69.

- ↑ Batty 2009, p. 279.

- ↑ Ptolemy Geographia III.8.1

- ↑ Sulimirski & 1972 p.104.

- ↑ Mommsen (1996) 315

- ↑ Pliny NH VI.6

- ↑ Talbert 2000, pp. 336,1209, maps 22,84.

- ↑ Amm. XXII.8.42

- ↑ Mommsen (1996) 315

- ↑ Batty (2008) map

- ↑ Marquand 1895, p. 550.

- ↑ Frazer 1898, pp. 429, 535.

- ↑ Chirică 1993, p. 158.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kovács 2009, p. 198.

- 1 2 3 4 Croitoru 2009, p. 402.

- ↑ Colledge 2000, p. 981.

- ↑ Kovács 2009, pp. 201,216.

- ↑ Aricescu 1980, pp. 11,46.

- ↑ Kovács 2009, p. 207.

- 1 2 3 4 Aricescu 1980, p. 46.

- ↑ Cortés 1995, pp. 191-193.

- ↑ Birley 2000, p. 168.

- ↑ Schiedel 1990.

- 1 2 3 4 Johnson 2011, p. 206.

- 1 2 3 Matei-Popescu 2003-2005, p. 309.

- 1 2 3 4 Petolescu 2007, p. 377.

- ↑ Aricescu 1980, p. 86.

- ↑ Tocilescu 1903, p. 31.

- ↑ Basotova 2007, p. 409.

- 1 2 3 Robertson Brown 2011, p. 80.

- ↑ Jones 1935, p. 577.

- ↑ Birley 2000, pp. 164-165.

- ↑ Robertson Brown 2011, pp. 80,82.

- ↑ Cortés 1995, pp. 188-191.

- 1 2 Robertson Brown 2011, p. 82.

- ↑ Clinton 2005, pp. 414-416.

- ↑ Schuddeboom 2009, pp. 213-214,231.

- ↑ Kłodziński 2010, pp. 7,9.

- ↑ Birley 2000, pp. 165,168.

- ↑ Robertson Brown 2011, pp. 81-82.

- 1 2 Croitoru 2009, p. 403.

- ↑ AE 1998 1113

- ↑ Croitoru 2009, p. 404.

- 1 2 Opreanu 1997, p. 248.

- ↑ Mateescu 1923, p. 255.

- ↑ Bichir 1980, p. 449.

- 1 2 3 Opreanu 1997, p. 249.

- ↑ Kovács 2009, p. 228.

- 1 2 3 Merills & Miles 2010, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 Birley 2000, p. 170.

- ↑ Parker 1958, p. 24.

- ↑ Schütte 1917, p. 143.

Bibliography

- AE: L'Année épigraphique

- Alföldi, Andreas (1944). Zu den Schicksalen Siebenbürgens im Altertum. Budapest.

- Aricescu, Andrei (1980). The army in Roman Dobrudja.

- Basotova, Maja (2007). "A new veteran of the legion VII Claudia from the colonia Flavia Scupi". Arheološki Vestnik. 58: 405–409.

- Batty, Roger (2008). Rome and the Nomads: the Pontic-Danubian region in Antiquity.

- Bichir, Gheorghe (1976): History and Archaeology of the Carpi from the 2nd to the 4th centuries AD (English Trans. BAR Series 16 i)

- Bichir, Gheorghe (1980). "Dacii liberi în secolele II - IV e.n.". Revista de Istorie. 33 (3): 443–468.

- Birley, Anthony R. (2000) [1987]. Marcus Aurelius: A Biography (2 ed.). Routledge.

- Chirică, Eduard (1993). "Une invasion "barbare" dans la Grèce Centrale au temps de Marc-Aurèle". Thraco-Dacica. 14: 157–158.

- Clinton, Kevin (2005). Eleusis, The Inscriptions on Stone: Documents of the Sanctuary of the Two Goddesses and Public Documents of the Deme. 1.

- Colledge, Malcolm A. R. (2000). "Art and architecture". Cambridge Ancient History. XI (2 ed.). pp. 966–983.

- Cortés, Juan Manuel (1995). "La datación de la expedición de los Costobocos: la subscripción de XXII K de Elio Arístides". Habis. 25: 187–193.

- Croitoru, Costin (2009). "Despre organizarea limes-ului la Dunărea de Jos. Note de lectură (V)". Istros. XV: 385–430.

- Dana, Dan (2003). "Les daces dans les ostraca du désert oriental de l'Égypte. Morphologie des noms daces". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 143: 166–186.

- Dana, Dan (2006). "The Historical Names of the Dacians and Their Memory: New Documents and a Preliminary Outlook". Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyai - Historia (1): 99–127.

- Duridanov, Ivan (1995). "Thrakische und dakische Namen". Namenforschung. Ein Internationales Handbuch zur Onomastik. 1. Berlin-New York: De Gruyter. pp. 820–840.

- Den Boeft, Jan; Drijvers, Jan Willem; Den Hengst, Daniel; Teitler, Hans C. (1995). Philological and Historical Commentaries on Ammianus Marcellinus. XXII. Groningen.

- Dessau, Hermann (1892). Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae. 1. Berlin.

- Detschew, Dimiter (1957). Die thrakischen Sprachreste. Vienna.

- Faliyeyev, Alexander (2007): Celtic Dacia

- Frazer, James George (1898). Pausanias's Description of Greece. 5.

- Georgiev, Vladimir (1983). "Thrakische und Dakische Namenkunde". Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt. II.29.2. Berlin - New York. pp. 1195–1213.

- Heather, Peter (2010). Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe. Oxford University Press.

- Jazdzewski, Konrad (1948). Atlas to the prehistory of the Slavs: Issue 2, Part 1. Lodz Towarzystwo Naukowe.

- Johnson, Diane (2011). "Libanius' Monody for Daphne (Oration 60) and the Eleusinios Logos of Aelius Aristides". In Schmidt, Thomas; Fleury, Pascale. Perceptions of the Second Sophistic and its times. pp. 199–214.

- Jones, William Henry Samuel (1935). Pausanias Description of Greece, Books VIII.22-X. Harvard University Press.

- Kazanski, Michel; Sharov, Oleg; Shchukin, Mark B. (2006) [2006]. Des Goths Aux Huns: Archaeological Studies on Late Antiquity and Early Medieval Europe (400-1000 A.D.): Le Nord De La Mer Noire Au Bas-Empire Et a L'epoque Des Grandes Migrations. : British Archaeological Reports. ISBN 978-1-84171-756-2.

- Kłodziński, Karol (2010). "Equestrian cursus honorum basing on the careers of two prominent officers of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius". In Tempore. 4: 1–15.

- Kolendo, Jerzy (1978). "Un Romain d'Afrique élevé dans le pays de Costoboces: à propos de CIL VIII 14667". Acta Musei Napocensis. 15: 125–130.

- Kovács, Péter (2009). Marcus Aurelius' rain miracle and the Marcomannic wars. Brill.

- Kropotkin, Vladislav V. (1977). "Denkmäler der Przeworsk-Kultur in der Westukraine und ihre Beziehungen zur Lipica- und Cernjachov-Kultur". In Chropovský, Bohuslav. Symposium. Ausklang der Latène-Zivilisation und Anfänge der germanischen Besiedlung im mittleren Donaugebiet. Bratislava. pp. 173–200.

- Macrea, Mihail (1970). "Les Daces libres à l'époque romaine". In Filip, Jan. Actes du VIIe Congrés International des Sciences Prehistoriques et Protohistoriques, Prague 21-27 août 1966. 2. pp. 1038–1041.

- Mateescu, George G. (1923). "I Traci nelle epigrafi di Roma". Ephemeris Dacoromana. Rome. I: 57–290.

- Matei-Popescu, Florian (2003–2005). "Note epigrafice I". SCIVA. 54-56: 303–312.

- Merrills, Andrew H.; Miles, Richard (2010), The Vandals, Wiley-Blackwell

- Maenchen-Helfen Otto J. (1973) The world of the Huns : studies in their history and culture edited by Max Knight, published by Berkeley, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-01596-7

- Mikołajczyk, Andrzej (1984). "The Transcarpathian finds of Geto-Dacian coins". Archaeologia Polona. 23: 49–66.

- Marquand, Allan in American Journal of Archaeology" (1895) Vol. 10, no.4

- Müllenhoff, Karl (1887). Deutsche altertumskunde. 2. Berlin.

- Mommsen, Theodor (1885/6, 1996 Eng. translation): A History of Rome under the Emperors

- Muratori, Lodovico Antonio (1740). Novus Thesaurus Veterum Inscriptionum. 2. Milan.

- Musset, Lucien (1994) [1965]. Les invasions: les vagues germaniques (3 ed.). Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

- Nandris, John (1976). "The Dacian Iron Age: A comment in a European Context". Festschrift für Richard Pittioni zum siebzigsten Geburtstag. I. Wien. pp. 723–736. ISBN 978-3-7005-4420-3.

- Opreanu, C. (1997). "Roman Dacia and its barbarian neighbours. Economic and diplomatic relations". Roman frontier studies 1995: proceedings of the XVIth International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies. pp. 247–252.

- Opreanu, C. (1994). "Neamurile barbare de la frontierele Daciei Romane si relatiile lor politico-diplomatice cu Imperiul". Ephemeris Napocensis, EPH IV – 14. Institutul de Arheologie şi Istoria Artei Cluj. ISSN 1220-5249.

- Ormerod, Henry Arderne (1997) [1924]. Piracy in the ancient world: an essay in Mediterranean history.

- Parker, Henry Michael Deane (1958) [1935]. A history of the Roman world from AD 138 to 337. London: Methuen.

- Petersen, Leiva; Wachtel, Klaus (1998). Prosopographia Imperii Romani. Saec. I, II, III. VI. Berlin-New York: De Gruyter.

- Petolescu, Constantin C. (2007). "Cronica epigrafică a României (XXVI, 2006)". SCIVA. 58 (3-4): 365–388.

- von Premerstein, Anton (1912). "Untersuchungen zur Geschichte des Kaisers Marcus". Klio. 12: 139–178.

- Robertson Brown, Amelia (2011). "Banditry or Catastrophe? History, Archaeology, and Barbarian Raids on Roman Greece". In Mathisen, Ralph W.; Shanzer, Danuta. Romans, barbarians, and the transformation of the Roman world. pp. 79–95.

- Russu, Ion Iosif (1959). "Les Costoboces". Dacia. NS 3: 341–352.

- Russu, Ion Iosif (1969). "Die Sprache der Thrako-Daker" ('Thraco-Dacian language'). Editura Stiintifica.

- Scheidel, Walter (1990). "Probleme der Datierung des Costoboceneinfalls im Balkanraum unter Marcus Aurelius". Historia. 39: 493–498.

- Schuddeboom, Feyo L. (2009). Greek Religious Terminology - Telete & Orgia. Brill.

- Schütte, Gudmund (1917). Ptolemy's maps of northern Europe: a reconstruction of the prototypes. Copenhagen.

- Shchukin, Mark B. (1989). Rome and the Barbarians in Central and Eastern Europe: 1st century B.C.-1st century A.D.

- Talbert, Richard J. A. (2000). Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World.

- Tocilescu, Grigore G. (1903). "Câteva monumente epigrafice descoperite în România". Revista pentru istorie, archeologie şi filologie. 9 (1): 3–83.

- Tomaschek, Wilhelm (1980a) [1893]. Die alten Thraker. I (2 ed.). Vienna.

- Tomaschek, Wilhelm (1980b) [1894]. Die alten Thraker. II.2 (2 ed.). Vienna.