Codex Cumanicus

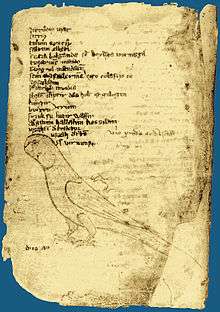

The Codex Cumanicus was a linguistic manual of the Middle Ages, designed to help Catholic missionaries communicate with the Cumans, a nomadic Turkic people. It is currently housed in the Library of St. Mark, in Venice (Cod. Mar. Lat. DXLIX).

Origin and content

The Codex likely developed over time. Mercantile, political and religious leaders, particularly in Hungary, sought effective communication with the Cumans from the time of their ascendency in the mid-11th century. As Italian city-states such as Genoa began to establish trade posts and colonies along the Black Sea coastline, the need for tools to learn the Kipchak language sharply increased.

The earliest parts of the Codex are believed to have originated in the 12th century or 13th century. It was likely added to substantially over time. The copy preserved in Venice dates from 1330 (July 11, 1330 on fol. 1r; see Drimba, p. 35 and Schmieder in Schmieder/Schreiner, p. XIII). The Codex consists of a number of independent works which were ultimately combined under one cover.

Historians generally divide it into two distinct and independent parts:

The first (fol. 1r-55v) is a practical handbook of the Kipchak tongue, containing glossaries of words in vulgar Italo-Latin and translations into Persian and Kipchak. This section has been styled the "Italian Part" or the "Interpreter's Book" of the Codex. Whether the Persian parts came through Kipchak intermediaries or whether Persian was a lingua franca for Mediterranean trade well known in Western Europe is a matter hotly debated by scholars.

The second part (fol. 56r-82v) is a collection of various religious texts (including a translation of the Lord's Prayer) and riddles in Kipchak, translated into Latin and Eastern Middle High German. This part of the Codex is referred to as the "German" or "Missionary's Book" and is believed to have been compiled by German Franciscans.

The Codex is generally regarded as accurate, but it differs slightly from other sources on Kipchak language.

Riddles

The "Cuman Riddles" (CC, 119-120; 143-148) are a crucial source for the study of early Turkic folklore. Andreas Tietze referred to them as "the earliest variants of riddle types that constitute a common heritage of the Turkic-speaking nations." Some of these riddles reached our days practically unchanged in Kazakh language. See examples below.

Among the riddles in the Codex are the following excerpts:

- Aq küymengin avuzı yoq. Ol yumurtqa.

- In Kazakh: Aq küymeniñ auzı joq. Ol jumırtqa

- "The white kibitka has no mouth (opening). That is the egg."

- Kökçä ulahım kögende semirir. Ol huvun.

- In Kazakh: Kökşe lağım kögende semirer. Ol qauın

- "my bluish kid at the tethering rope grows fat, The melon."

- Oturğanım oba yer basqanım baqır canaq. Ol zengi.

- In Kazakh: Otırğanım oba jer basqanım baqır şanaq. Ol uzengi

- "Where I sit is a hilly place. Where I tread is a copper bowl. The stirrup."

Example

The Codex's Pater Noster reads:

Atamız kim köktesiñ. Alğışlı bolsun seniñ atıñ, kelsin seniñ xanlığıñ, bolsun seniñ tilemekiñ – neçik kim kökte, alay [da] yerde. Kündeki ötmegimizni bizge bugün bergil. Dağı yazuqlarımıznı bizge boşatqıl – neçik biz boşatırbız bizge yaman etkenlerge. Dağı yekniñ sınamaqına bizni quurmağıl. Basa barça yamandan bizni qutxarğıl. Amen!

In English, the text is:

Our Father which art in heaven. Hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done in earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread. And forgive us our sins as we forgive those who have done us evil. And lead us not into temptation, But deliver us from evil. Amen.

In Kazakh, the text is:

Atamiz kim koktesin. Alğıstı bolsin seniñ atiñ, kelsin seniñ xanliğıñ, bolsin seniñ tilegeniñ - kalai kim kokte, solai da jerde. Kundelikti nanimizdi bizge bugin ber. Tağı jazıqtarimizdi bizge bosat - kalai biz bosatarmiz bizge jaman etkenderge. Tağı jınnıñ (şaitannıñ) sınağına bizdi qaldırma. Barşa jamannan bizdi qutqar. Aumin!

In Turkish, the text is:

Atamız ki göktesin. Alkışlı olsun senin adın, gelsin senin hanlığın, olsun senin dilemeğin – nice ki gökte, öyle (de) yerde. Gündelik ekmeğimizi bize bugün ver. Dahi yazıklarımızı (suçlarımızı) bize boşat – nice biz boşatırız (bağışlarız) bize yaman (kötülük) edenleri. Dahi şeytanın (yekin) sınamağına bizi koyurma. Tüm yamandan (kötülükten) bizi kurtar. Amin!

- Dr. Peter B. Golden on the Codex

- Italian Part of “Codex Cumanicus”, pp. 1 - 55. (38,119 Mb)

- German Part of “Codex Cumanicus”, pp. 56 - 83. (5,294 Mb)

- Schmieder, Felicitas et Schreiner, Peter (eds.), Il Codice Cumanico e il suo mondo. Atti del Colloquio Internazionale, Venezia, 6-7 dicembre 2002. Roma, Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 2005, XXXI-350 p., ill. (Centro Tedesco di Studi Veneziani, Ricerche, 2).

- Drimba, Vladimir, Codex Comanicus. Édition diplomatique avec fac-similés, Bucarest 2000.

- Davud Monshizadeh, Das Persische im Codex Cumanicus, Uppsala: Studia Indoeuropaea Upsaliensia, 1969.

- Argunşah, Mustafa; Güner, Galip, Codex Cumanicus, Kesit Yayınları, İstanbul, 2015, 1080 pp. (https://www.academia.edu/16819097/Codex_Cumanicus)

External links

- Full text of the Codex Cumanicus

- List of titles and examples from Codex Cumanicus

- http://www.kesityayinlari.com/vitrin/prddet.php?pid=189

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Codex Cumanicus. |