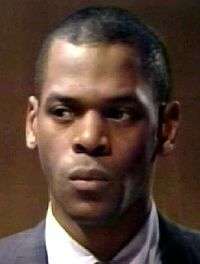

Clyde Tavernier

| Clyde Tavernier | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| EastEnders character | |||||||||||||||||

| Portrayed by | Steven Woodcock | ||||||||||||||||

| Duration | 1990–93 | ||||||||||||||||

| First appearance |

Episode 566 5 July 1990 | ||||||||||||||||

| Last appearance |

Episode 885 22 July 1993 | ||||||||||||||||

| Introduced by | Michael Ferguson | ||||||||||||||||

| Classification | Former; regular | ||||||||||||||||

| Profile | |||||||||||||||||

| Occupation |

Barman Boxer | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Clyde Tavernier is a fictional character from the BBC soap opera EastEnders, played by Steven Woodcock. Introduced on 5 July 1990, Clyde featured in prominent storylines including an inter-racial relationship with Michelle Fowler (Susan Tully) and being framed for the murder of publican Eddie Royle (Michael Melia).[1] The character was written out in 1993 and was given a happy ending, leaving on 22 July 1993.

Storylines

Backstory

Clyde was the first-born son to Etta and Celestine Tavernier (Jacqui Gordon-Lawrence and Leroy Golding). After his birth in Trinidad in 1968, his family moved to the UK. Growing up in London, Clyde was subject to racism and police harassment, which made him angry and somewhat bitter. In adulthood, Clyde struggled to find direction. He lazed around, did odd jobs, and took up boxing. Clyde met a woman named Abigail Chadwick and they had a child together, a son named Kofi. Clyde and Abigail split up and Kofi was taken to Bristol by his mother to live with his grandparents. When Abigail was killed in a car crash, it was agreed that Kofi would remain living with his maternal grandparents.

1990–93

Clyde moves to Albert Square in July 1990 with his family. Clyde gets a job working in The Queen Victoria public house. Clyde becomes prime suspect for a series of thefts that were occurring in the pub. Clyde's boss, Eddie Royle (Michael Melia), suspects Clyde is behind the incidents as he is the only black barman. However, Clyde is later cleared of any wrongdoing. Clyde desperately misses his son, Kofi Tavernier (Marcel Smith), and when he discovers that Kofi's grandparents are planning to take his child to live permanently in Jamaica, he tails them to the airport to stop them. Despite initial uncertainty Clyde is given custody of his son and Kofi moves in with Clyde. Clyde starts a relationship with Michelle Fowler (Susan Tully); their inter-racial relationship causes a stir in the community. Clyde resumes boxing, spurred on by Phil (Steve McFadden) and Grant Mitchell (Ross Kemp), who hope to exploit him in the ring by pitting him against a superior fighter and betting against him. However their plan backfires when an overfaced Clyde manages to win the fight, despite the odds being severely stacked against him. Clyde is later trained to box by Eddie, but animosity between him and Eddie resurfaces when Eddie attempts to get Clyde to throw a fight in a betting scam. Clyde refuses, but his altercations with Eddie come back to haunt him when he becomes the prime suspect in Eddie's murder soon after.

Clyde discovers Eddie's bloody body in the square and unwittingly picks up the knife that has been used to kill him. Panicking, Clyde leaves the scene and disposes of the murder weapon, but is seen by the real murderer, Nick Cotton (John Altman), who proceeds to frame Clyde for the deed. With a clear motive and a key witness, Clyde finds it difficult to convince anyone of his innocence. Clyde feels that he was the victim of a racist conspiracy and sensing his imminent arrest he decides to go 'on the run' with Kofi. Michelle sticks by him and she and her daughter Vicki Fowler (Samantha Leigh Martin) leave Walford with Clyde, with the hope of starting a new life together in France. Their bid for freedom is not to be as Clyde is apprehended in Portsmouth before he can leave the country; he is subsequently imprisoned. He only secures release three months later when a witness, Joe Wallace (Jason Rush) comes forward and identifies Nick as Eddie's real killer. Upon Clyde's release, his relationship with Michelle abruptly ends when he catches her in bed with another man, Jack Woodman (James Gilbey). The Taverniers are visited by Gidea Thompson (Sian Martin), who is Jules' granddaughter from an adulterous affair he had in his 20s. Clyde and Gidea grow close, and even though they are cousins they embark on a relationship together. Jules disapproves when he finds out but Clyde ignores his protests, and in July 1993 he decides to leave Walford to start a new life with Gidea in Trinidad.

Creation and development

In the latter part of 1989, EastEnders acquired a new executive producer named Michael Ferguson, who took over from Mike Gibbon. Ferguson had previously been a producer on ITV's The Bill – a hard-hitting, gritty and successful police drama, which seemed to be challenging EastEnders in providing a realistic vision of modern life in London. Due to his success on The Bill, Peter Cregeen, the Head of Series at the BBC, poached Ferguson to become executive producer of EastEnders.[2]

Following a relatively unsuccessful inclination towards comic storylines throughout 1989, Ferguson decided to take the soap in a new direction in 1990. Big changes were implemented both off-screen and on-screen.[2] Ferguson altered the way the episodes were produced, changed the way the storylines were conceptualised and introduced a far greater amount of location work than had previously been seen. EastEnders scriptwriter Colin Brake said that it was a challenging period, but "the results on-screen were a programme with a new sense of vitality, and a programme more in touch with the real world than it had been for a while".[2]

As a consequence of these changes, a large number of characters were axed in early 1990 as the new production machine cleared way for a new direction and new characters.[2] Among the new characters were the Jamaican Tavernier family, who collectively arrived on-screen in July 1990, composed of grandfather Jules (Tommy Eytle), his son and daughter-in-law Celestine (Leroy Golding) and Etta (Jacqui Gordon-Lawrence), their eldest son Clyde (Steven Woodcock), and their twins Lloyd (Garey Bridges) and Hattie (Michelle Gayle). Later Clyde's son Kofi Tavernier was introduced. Colin Brake described the Taverniers as the major new additions that year, and it heralded the first time that an entire family had joined the serial all at once. Their introduction was also described as a well-intentioned attempt to portray a wider range of black characters than had previously been achieved on the soap.[2]

It took a long time to cast the complete Tavernier family. Once EastEnders became a success, the producers had no difficulties in finding "good actors" who wanted to join the cast; however, what became hard was finding families—combinations of performers who "look and sound as though they could be related."[3] According to producers Corinne Hollingworth and Pat Sandys, the Taveriner family were especially difficult as four generations of the family were being featured. Hollingworth has commented "The most difficult job we've had was finding six black actors who fitted the bill for the Tavernier family. Here we needed two teenagers who looked around fifteen but were actually older, had left school and had mature attitudes to work. They had to love music, hanging around in tracksuits and most important, they had to look as if they could be twins. And for Clyde, we needed someone who looked as though he'd been a boxer but also seemed thoughtful."[3]

Author Hilary Kingsley described Clyde as someone who "has never accepted that black people have to tolerate prejudice without protest." She added that "Clyde has good reason to feel bitter, thanks to years of being harassed by the police. Yet he had never broken the law".[3] She suggested that he was a character who sometimes lacked sense.".[3] Rupert Smith has classified Clyde as a "poster boy" the type of character whose principal purpose "seems to be to please the show's sizeable straight female and gay audience".[4] Woodcock was a keen boxer, and this was utilised on-screen in 1991, when Clyde took up the sport.[3] Smith has claimed that this gave the programme-makers the opportunity to allow Clyde to take his shirt off on-screen, which according to Smith, "he did at the drop of a hat".[4]

Clyde's most prominent storyline surrounded his seeming involvement in the murder of publican Eddie Royle (Michael Melia). Colin Brake has stated that it was the biggest storyline of the year.[2] In the storyline, Clyde was framed for the murder by the real killer, Nick Cotton (John Altman). As prime suspect, Clyde decided to flee the country with his son and his girlfriend Michelle. They went to Portsmouth with the hope of catching a private ferry to France so they could start a new life together, but they were arrested whilst trying to board the boat.[5] Brake has nominated one of the episodes focusing on Clyde's attempted police escape as 1991's "pick of the year".[2] The episode was written by Tony Jordan and was played as if it was the actual last appearance of Michelle, who had been pivotal in the series up until that point. Brake suggested there "was a strong sense of tension as the episode built to the inevitable ending, with Michelle and Clyde arrested by the police on the verge of boarding a private boat that would have taken them to France."[2] The episode was directed by Mike Dormer and aired on 14 November 1991. Brake described it as "the most exciting thriller episodes of EastEnders" and suggested that it "allowed a new side of both Clyde and Michelle to be seen, and put real pressure on their already fragile relationship".[2]

Clyde's time in the soap came to an end in July 1993. The Independent reported that the character was being written out of EastEnders. Clyde was one of several characters to be written out that year in what the press dubbed the "Albert Square Massacre".[6] Clyde was given a happy ending on-screen; he departed after falling in love with a second cousin, and moved to live in Trinidad.

Reception

Writer Rupert Smith has suggested that Clyde's purpose was "almost entirely decorative" and that Clyde had little else to do in EastEnders except take his clothes off, other than to "dally improbably with Michelle and to do the odd bit of kidnapping."[4] In the 1992 book Come on down?: popular media culture in post-war Britain, the authors have referenced Clyde and the rest of the Tavernier family as non-white characters who appeared to have been integrated into part of the predominantly white communal setting of the soap. However, they suggested that this attempt at inclusion "is the single clue to an understanding of why EastEnders is a development of an old form of representation of working-class life. The ethnic minority households are accepted in the working-class community, but the black, white and Asian families remain culturally distinct." They suggested that there was no attempt to portray hybridity between black-white cultures.[7]

Robert Clyde Allen has discussed the Tavernier family in his 1995 book To be continued--: soap operas around the world. He suggested that black characters in EastEnders were incorporated into the working-class culture of the soap as opposed to offering something different from it. He noted that the Taverniers, the focus of black characters in the early 1990s, for a while had the same mixture of generations and attitudes that characterized the Fowlers, one of the soap's core white families who had a dominant position in the series. However he stated that "somewhat typically [...] the family broke up".[8]

References

- ↑ "EastEnders at 15: tragic moments; 1991-1993.". Sunday Mail. 16 April 2000. Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Brake, Colin (1995). EastEnders: The First 10 Years: A Celebration. BBC Books. ISBN 0-563-37057-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kingsley, Hilary (1990). The EastEnders Handbook. BBC books. ISBN 978-0-563-36292-0.

- 1 2 3 Smith, Rupert (2005). EastEnders: 20 years in Albert Square. BBC books. ISBN 0-563-52165-1.

- ↑ "EastEnders". EastEnders. 1991-11-14. BBC. BBC1.

- ↑ "Tabloid TV". London: The Independent. 30 March 1993. Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- ↑ Dominic Strinati and Stephen Wagg (1992). Come on Down?: Popular Media Culture in Post-War Britain. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-06327-2.

- ↑ Robert Clyde Allen (1995). To be Continued--: Soap Operas Around the World. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-11007-5.