Citizens' Councils

Citizens' Councils logo | |

| Abbreviation | WCC |

|---|---|

| Successor | Council of Conservative Citizens |

| Formation | July 11, 1954 |

Membership | 60,000 (1955) |

Founder | Robert Patterson |

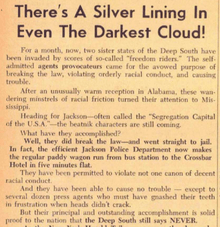

The Citizens' Councils (also referred to as White Citizens' Councils) were an associated network of white supremacist organizations in the United States, concentrated in the South. The first was formed on July 11, 1954.[1] After 1956, it was known as the Citizens' Councils of America. With about 60,000 members across the United States,[2] mostly in the South, the groups were founded primarily to oppose racial integration of schools, but they also opposed voter registration efforts and integration of public facilities during the 1950s and 1960s. Members used severe intimidation tactics including economic boycotts, firing people from jobs, propaganda, and violence against citizens and civil-rights activists.

By the 1970s, following passage of federal civil rights legislation in the mid-1960s and enforcement of constitutional rights by the federal government, the influence of the Councils had waned considerably yet remained an institutional basis for the majority of white residents in Mississippi. The successor organization to the White Citizens' Councils is the St. Louis based Council of Conservative Citizens, founded in 1985[2] to continue collaborations between Ku Klux Klan and white supremacist political agendas in the United States. Republican politician and past Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott of Mississippi was a member[3] while SC Senator Jesse Helms and GA Representative Bob Barr were both strong supporters of the Council of Conservative Citizens; David Duke also spoke at a fund raising event, while Patrick Buchanan's campaign manager was linked to both Duke and the Council.[4] In 1996, a Charleston, SC, drive-by shooting by Klan members of three African American males occurred after a Council rally; Dylann Roof, responsible for the 2015 murder of nine Emanuel AME church members in Charleston, espoused Council of Conservative Citizens rhetoric in a manifesto.[5]

History

In 1954 the US Supreme Court ruled in Brown vs. Board of Education that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. Some sources claim that the White Citizens' Council first started after this in Greenwood, Mississippi.[6] Others say that it originated in Indianola, Mississippi.[7] The recognized leader was Robert B. Patterson of Indianola,[1][8] a plantation manager and a former captain of the Mississippi State University football team. Additional chapters spread to other southern towns. At this time, most southern states enforced racial segregation of all public facilities; in places where local laws did not require segregation, Jim Crow harassment enforced it. After preliminary post-Civil War Reconstruction efforts led by blacks and poorer whites, the subsequent period from 1890 to 1908 led to disfranchisement of most blacks through the passing of new constitutions and other laws making voter registration and elections more difficult, and led to the founding of the Ku Klux Klan. Despite civil rights organizations winning some legal challenges, most blacks in the 1950s were still retaliated against for registering to vote, as well as for riding buses and sitting at lunch counters,[9] in the South and remained so even after passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Patterson and his followers formed the White Citizens Council in part to respond with economic retaliation and violence to increased civil rights activism. The Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL), a grassroots civil rights organization founded in 1951 by T. R. M. Howard of the all-black town Mound Bayou, Mississippi was also 40 miles from Indianola. Aaron Henry, a later official in the RCNL and the future head of the Mississippi NAACP[10] had met Patterson during their childhood.

Within a few months, the White Citizens Council had attracted similar racist members; new chapters developed beyond Mississippi in the rest of the Deep South. The Council often had the support of the leading white citizens of many communities, including business, law enforcement, civic and sometimes religious leaders, many of whom were members. Member businesses, such as newspaper publishing, legal representation, medical service, were known for collectively acting against registered voters whose names were first published in local papers before additional retaliatory actions were taken against them.

Economic retaliation and violence

Unlike the Ku Klux Klan but working in unison, the White Citizens Council met openly, and was seen superficially as "pursuing the agenda of the Klan with the demeanor of the Rotary Club."[11] Although the White Citizens Council publicly eschewed the use of violence,[1] the economic and political tactics used against registered voters and activists embraced institutional violence. The White Citizens Council members collaborated to threaten jobs, causing people to be fired or evicted from rental homes; they boycotted businesses, ensured that activists could not get loans, among other tactics.[6] As historian Charles Payne notes, "Despite the official disclaimers, violence often followed in the wake of Council intimidation campaigns."[11] Occasionally some Councils directly incited violence, such as lynchings, shootings, rapes, and arson.

For instance, in Montgomery, Alabama, during the Montgomery Bus Boycott, at which Senator James Eastland "ranted against the NAACP"[12] at a large openly held Council meeting in the Garrett Coliseum, a mimeographed flyer publicly espousing extreme racial White Citizens Council and Ku Klux Klan rhetoric was distributed, saying:

When in the course of human events, it becomes necessary to abolish the Negro race, proper methods should be used. Among these are guns, bows and arrows, sling shots and knives. We hold these truths to be self-evident that all whites are created equal with certain rights; among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of dead niggers.[13]

The Citizens' Councils used economic tactics against African Americans whom they considered as supportive of desegregation and voting rights, or for belonging to the NAACP, or even suspected of being activists; the tactics included "calling in" the mortgages of black citizens, denying loans and business credit, pressing employers to fire certain people, and boycotting black-owned businesses.[14] In some cities, the Councils published lists of names of NAACP supporters and signers of anti-segregation petitions in local newspapers in order to encourage economic retaliation.[15] For instance, in Yazoo City, Mississippi in 1955, the Citizens' Council published in the local paper the names of 53 signers of a petition for school integration. Soon afterward, the petitioners lost their jobs and had their credit cut off.[16] As Charles Payne puts it, the Councils operated by "unleashing a wave of economic reprisals against anyone, Black or white, seen as a threat to the status quo."[11] Their targets included black professionals such as teachers, as well as farmers, high school and college students, shop owners, and housewives.

Medgar Evers' first work for the NAACP on a national level involved interviewing Mississippians who had been intimidated by the White Citizens' Councils and preparing affidavits for use as evidence against the Councils if necessary.[17] Evers was assassinated in 1963 by Byron De La Beckwith, a member of the White Citizens' Council as well as the Ku Klux Klan.[18] The Citizens' Council paid his legal expenses in his two trials in 1964, which both resulted in hung juries.[19] In 1994, Beckwith was tried by the state of Mississippi based on new evidence, in part revealed by a lengthy investigation by the Jackson Clarion Ledger; he was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison.[20]

Political influence

Many leading state and local politicians were members of the Councils; in some states, this gave the organization immense influence over state legislatures. In Mississippi, the State Sovereignty Commission funded the Citizens' Councils, in some years providing as much as $50,000. This state agency, funded by the taxes paid by all citizens, also shared information with the Councils that it had collected through investigation and surveillance of integration activists.[21] For example, Dr. M. Ney Williams was both a director of the Citizens' Council and an adviser to governor Ross Barnett of Mississippi.[22] Barnett was a member of the Council, as was Jackson mayor Allen C. Thompson.[23] In 1955, in the midst of the bus boycott, all three members of the Montgomery city commission in Alabama announced on television that they had joined the Citizens' Council.[24]

Numan Bartley wrote, "In Louisiana the Citizens' Council organization began as (and to a large extent remained) a projection of the Joint Legislative Committee to Maintain Segregation."[25] In Louisiana, leaders of the original Citizens' Council included State Senator and gubernatorial candidate William M. Rainach, U.S. Representative Joe D. Waggonner, Jr., the publisher Ned Touchstone, and Judge Leander Perez, considered the political boss of Plaquemines and St. Bernard parishes near New Orleans.[26] After he left the editorship of the Shreveport Journal in 1971, George W. Shannon relocated to Jackson, Mississippi, to work on The Citizen, a monthly magazine of the Citizens' Council. The Citizen halted publication in January 1979, by which time Shannon had returned to Shreveport.[27]

On July 16, 1956, "under pressure from the White Citizens Councils,"[28] the Louisiana State Legislature passed a law mandating racial segregation in nearly every aspect of public life; much of the segregation already existed under Jim Crow custom. The bill was signed into law by governor Earl Long on 16 July 1956 and went into effect on 15 October 1956. The act read, in part:

An Act to prohibit all interracial dancing, social functions, entertainments, athletic training, games, sports, or contests and other such activities; to provide for separate seating and other facilities for white and negroes [lower case in original] ... That all persons, firms, and corporations are prohibited from sponsoring, arranging, participating in or permitting on premises under their control ... such activities involving personal and social contact in which the participants are members of the white and negro races ... That white persons are prohibited from sitting in or using any part of seating arrangements and sanitary or other facilities set apart for members of the negro race. That negro persons are prohibited from sitting in or using any part of seating arrangements and sanitary or other facilities set apart for white persons.[28]

School desegregation and the demise of the councils

Throughout the last half of the 1950s, the White Citizens' Councils produced racist children's books that taught that heaven (in the Christian conception) is segregated.[29] The White Citizens' Council in Mississippi prevented school integration until 1964.[30] As school desegregation increased in some parts of the South, in some communities the White Citizens' Council sponsored "council schools," private institutions set up for white children, as these were beyond the reach of the ruling on public schools.[31] Many of these private "segregation academies" continue to operate today.

By the 1970s, as white Southerners' attitudes toward desegregation began to change following passage of federal civil rights legislation and enforcement of integration and voting rights in the 1960s, the activities of the White Citizens' Councils began to wane. The Council of Conservative Citizens, founded by former White Citizens' Council members,[2] continued the agendas of the earlier Councils.

See also

- African-American Civil Rights Movement (1896–1954)

- African-American Civil Rights Movement (1954–68)

- Timeline of African-American Civil Rights Movement

References

- 1 2 3 "July 11, 1954". University of Southern Mississippi. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Council of Conservative Citizens". Anti-Defamation League. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ↑ Washington Post http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/special/clinton/stories/barr121298.htm

- ↑ Anti Defamation League http://archive.adl.org/mwd/ccc.html

- ↑ Post and Courier http://www.postandcourier.com/article/20150622/PC16/150629806/presidential-candidates-give-away-cash-from-council-of-conservative-citizens

- 1 2 "White Citizens' Councils aimed to maintain 'Southern way of life'". The Jackson Sun. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ↑ Roberts, Gene and Hank Klibanoff (2006). The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 66. ISBN 0-679-40381-7.

- ↑ Cobb, James C. (23 December 2010). "The Real Story of the White Citizens' Council". History News Network. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- ↑ Charles E. Cobb Jr. "This Nonviolent Stuff'll Get You Killed."

- ↑ Beito, David T.; Beito, Linda Royster (8 April 2009). Black maverick: T.R.M. Howard's fight for civil rights and economic power. University of Illinois Press. pp. 95–97. ISBN 978-0-252-03420-6. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- 1 2 3 Payne, Charles M. (16 March 2007). I've Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. University of California Press. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-0-520-25176-2. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ↑ Stephen Oates, Let the Trumpet Sound, pages 91-92

- ↑ Stephen Oates Let the Trumpet Sound pages 91-92

- ↑ Dittmer, John (1 May 1995). Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi. University of Illinois Press. pp. 46–48. ISBN 978-0-252-06507-1. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ↑ McMillen, Neil R. (1971). The Citizen's Council: Organized Resistance to the Second Reconstruction, 1954–1964. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 211. ISBN 0-252-00177-X.

- ↑ Wakefield, Dan (22 October 1955). "Respectable Racism". The Nation. reprinted in Carson, Clayborne; Garrow, David J.; Kovach, Bill (2003). Reporting Civil Rights: American journalism, 1941–1963. Library of America. pp. 222–227. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ↑ Vollers, Maryanne (April 1995). Ghosts of Mississippi: The Murder of Medgar Evers, the Trials of Byron de la Beckwith, and the Haunting of the New South. Little, Brown. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-0-316-91485-7. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- ↑ Burford, Sarah (19 Nov 2011). "Newest Navy Vessel Named for Civil Rights Martyr Medgar Evers". Afro - American Red Star. Washington, D.C. p. A.1.

- ↑ Luders, Joseph (Jan 2006). "The Economics of Movement Success: Business Responses to Civil Rights Mobilization". The American Journal of Sociology. 111 (4): 963–0_10. doi:10.1086/498632.

- ↑ Stout, David (January 23, 2001). "Byron De La Beckwith Dies; Killer of Medgar Evers Was 80". The New York Times. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ Vollers, Maryanne (April 1995). Ghosts of Mississippi: The Murder of Medgar Evers, the Trials of Byron de la Beckwith, and the Haunting of the New South. Little, Brown. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-316-91485-7. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- ↑ Leonard, George B.; Harris, T. George; Wren, Christopher S. (31 December 1962). "How a Secret Deal Prevented a Massacre at Ole Miss". Look. Reprinted in Carson, Clayborne; Garrow, David J.; Kovach, Bill (2003). Reporting Civil Rights: American journalism, 1941–1963. Library of America. pp. 671–701. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ↑ Sitton, Claude (13 June 1963). "N.A.A.C.P. Leader Slain in Jackson; Protests Mount". New York Times. reprinted in Carson, Clayborne; Garrow, David J.; Kovach, Bill (2003). Reporting Civil Rights: American journalism, 1941–1963. Library of America. pp. 831–835. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ↑ Reddick, L.D. (Winter 1956). "The Bus Boycott in Montgomery". Dissent. reprinted in Carson, Clayborne; Garrow, David J.; Kovach, Bill (2003). Reporting Civil Rights: American journalism, 1941–1963. Library of America. pp. 252–265. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ↑ Bartley, Numan V. (1999). The Rise of Massive Resistance: Race and Politics in the South during the 1950s. LSU Press. p. 86ff. ISBN 978-0-8071-2419-2. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ↑ McMillen, Neil R. (1971). "Chapter IV Louisiana: And Catholics Too". The Citizen's Council: Organized Resistance to the Second Reconstruction, 1954–1964. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. pp. 59–72. ISBN 0-252-00177-X.

- ↑ "Periodicals: The Citizen". olemiss.edu. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- 1 2 Bagdikian, Ben (20 & 22 October 1957). "You Can't Legislate Human Relations". The Providence Journal and Evening Bulletin. Check date values in:

|date=(help) reprinted in Carson, Clayborne; Garrow, David J.; Kovach, Bill (2003). Reporting Civil Rights: American journalism, 1941–1963. Library of America. pp. 390–395. Retrieved 15 September 2011. - ↑ Tyson, Timothy B. (3 May 2005). Blood Done Sign My Name: A True Story. Random House. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-4000-8311-4.

- ↑ Dr. John Dittmer, "'Barbour is an Unreconstructed Southerner': Prof. John Dittmer on Mississippi Governor's Praise of White Citizens' Councils", 22 December 2010 video report by Democracy Now!, accessed 21 November 2011

- ↑ McMillen, Neil R. (1971). The Citizen's Council: Organized Resistance to the Second Reconstruction, 1954–1964. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 301. ISBN 0-252-00177-X.

Further reading

- Geary, Daniel and Sutton, Jennifer. "Resisting the Wind of Change: The Citizens' Councils and European Decolonization," in Cornelius A. van Minnen and Manfred Berg, eds., The U.S. South and Europe, University of Kentucky Press, 2013.

- McMillen, Neil R. (1 October 1994). The Citizens' Council: Organized Resistance to the Second Reconstruction, 1954–64. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06441-8. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

External links

- The Citizens' Council - Historical resource website by Edward Sebesta, with digitized copies of the full run of The Citizens Council newspaper, 1955–1961. Originally a publication of the Mississippi Citizens' Council, the monthly publication became the official paper of the Citizens' Councils of America in October 1956.

- Available in PDF from Internet Archive.

- "Civil Rights Documentation Project", University of Southern Mississippi

- Dr. John Dittmer, "'Barbour is an Unreconstructed Southerner': Prof. John Dittmer on Mississippi Governor's Praise of White Citizens' Councils", 22 December 2010 video report by Democracy Now!

- "Schwerner, Chaney, and Goodman: The Struggle for Justice", American Bar Association

- FBI files on the Citizens' Council Movement