Eski Imaret Mosque

| Eski Imaret Mosque Eski Imaret Câmîi | |

|---|---|

|

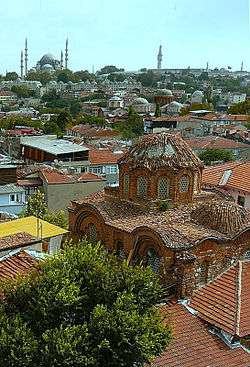

An Aerial view showing the location of the building. In the background Suleymaniye Mosque and the Beyazıt Tower | |

| Basic information | |

| Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°1′18″N 28°57′18″E / 41.02167°N 28.95500°E |

| Affiliation | Sunni Islam |

| Year consecrated | Short after 1453 |

| Architectural description | |

| Architectural type | church with cross-in-square plan |

| Architectural style | Middle Byzantine - Comnenian |

| Completed | Short before 1087 |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | brick, stone |

Eski Imaret Mosque (Turkish: Eski Imaret Camii) is a former Eastern Orthodox church converted into a mosque by the Ottomans. The church has traditionally been identified with that belonging to the Monastery of Christ Pantepoptes (Greek: Μονή του Χριστού Παντεπόπτη), meaning "Christ the all-seeing". It is the only documented 11th-century church in Istanbul which survives intact, and represents a key monument of middle Byzantine architecture. Despite that, the building remains one among the least studied of the city.

Location

The building lies in Istanbul, in the district of Fatih, in the neighbourhood of Zeyrek, one of the poorest areas of the walled city. It is located less than one kilometer to the northwest of the complex of Zeyrek.

History

Some time before 1087, Anna Dalassena, mother of Byzantine Emperor Alexius I Comnenus, built on the top of the fourth hill of Constantinople a nunnery, dedicated to Christos Pantepoptes, where she retired at the end of her life, following Imperial custom.[1] The convent comprised a main church, also dedicated to the Pantepoptes.

On April 12, 1204, during the siege of Constantinople, Emperor Alexios V Doukas Mourtzouphlos set his headquarters near the Monastery. From this vantage point he could see the Venetian fleet under command of Doge Enrico Dandolo deploying between the monastery of the Euergetes and the church of St. Mary of the Blachernae before attacking the city.[2] After the successful attack he took flight abandoning his purple tent on the spot, and so allowing Baldwin of Flanders to spend his victory night inside it.[2] The complex was sacked by the crusaders, and afterward it was assigned to Benedictine monks of San Giorgio Maggiore.[3] During the Latin occupation of Constantinople (1204–1261) the building became a Roman Catholic church.

Based on this information, the Patriarch Constantius I (1830–1834) identified the Eski Imaret with the Pantepoptes church.[4] This identification has been largely accepted since, with the exception of Cyril Mango, who argued[5] that the building's location did not actually allow for complete overview of the Golden Horn, and proposed the area currently occupied by the Yavuz Sultan Selim Mosque as an alternative site for the Pantepoptes Monastery.[6] Austay-Effenberger and Effenberger agreed with Mango, and proposed an identification with the Church of St. Constantine, founded by the Empress Theophano in the early 10th century, highlighting its similarities to the contemporaneous Lips Monastery.[7]

Immediately after the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the church became a mosque, while the buildings of the monastery were used as zaviye,[8] medrese and imaret for the nearby Mosque of Fatih, which was then under construction.[9] The Turkish name of the mosque ("the mosque of the old soup kitchen") refers to this.

The complex was ravaged several times by fire, and the last remains of the monastery disappeared about one century ago.[1] Until 1970 the building was used as a koran school, and that use rendered it almost inaccessible for architectural study. In 1970, the mosque was partially closed off and restored by the Turkish architect Fikret Çuhadaroglu. Despite that, the building appears to be in rather poor condition.

Architecture

The building lies on a slope which overlooks the Golden Horn, and rests on a platform which is the ceiling of a cistern. It is closely hemmed in all sides, making an adequate view of the exterior difficult. Its masonry consists of brick and stone, and uses the technique of recessed brick; it is the oldest extant building of Constantinople where this technique can be observed, which is typical of the Byzantine architecture of the middle empire.[10] In this technique, alternate coarses of bricks are mounted behind the line of the wall, and are plunged in a mortar bed. Due to that, the thickness of the mortar layers is about three times greater than that of the brick layers. The brick tiles on its roof are unique among the churches and mosques of Istanbul, which are otherwise covered with lead.

The plan belongs to the cross-in-square (or quincunx) type with a central dome and four vaulted crossarms, a sanctuary to the east and an esonarthex and an exonarthex to the west. This appears to be an addition of the Palaiologan period, substituting an older portico, and is divided into three bays. The lateral ones are surmounted by cross vaults, the central one by a dome.

A unique feature of this building is the U-shaped gallery which runs over the narthex and the two western bays of the quincunx. The gallery has windows opening towards both the naos and the crossarm. It is possible that the gallery was built for the private use of the Empress-Mother.[1]

As in many of the surviving Byzantine churches of Istanbul, the four columns which supported the crossing were replaced by piers, and the colonnades at either ends of the crossarms were filled in.[1] The piers divide the nave into three aisles. The side aisles lead into small clover-leaf shaped chapels to the east, connected to the sanctuary and ended to the east, like the sanctuary, with an apse. These chapels are the prothesis and diaconicon. The Ottomans resurfaced the apses and built a minaret, which does not exist any more.

The dome, which during the Ottoman period was given a helmet-like shape, recovered its original scalloped roofline in the restoration of 1970. This is typical of the churches of the Macedonian period.[11] The tent-like roofing of the gallery has been also replaced with tiles that follow the curves of the vaulting.[1]

The exterior has occasional decorative motifs, like sunbursts, meanders, basket-wave patterns and cloisonnés: the latter motif is typical of the Greek architecture of this period but unknown elsewhere in Constantinople. Of the original interior, nothing remains but some marble moldings, cornices, and doorframes.

Despite its architectural significance, the building is still one among the least studied monuments of Istanbul.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mathews (1976), p. 59

- 1 2 Van Millingen (1912), p. 214

- ↑ Jacobi (2001), p. 287

- ↑ Asutay-Effenberger & Effenberger (2008), p. 13

- ↑ Mango, Cyril (1998). "Where at Constantinople was the Monastery of Christos Pantepoptes?". Δελτίον τῆς. Xριστιανικῆς Ἀρχαιολογικῆς Ἑταιρείας. 20: 87–88.

- ↑ Asutay-Effenberger & Effenberger (2008), pp. 13–14

- ↑ Asutay-Effenberger & Effenberger (2008), pp. 13–40

- ↑ A Zaviye was a building designed specifically for gatherings of a Sufi or dervish brotherhood.

- ↑ Müller-Wiener (1977), Sub Voce.

- ↑ Krautheimer (1986), p. 400

- ↑ Krautheimer (1986), p. 407

Sources

- Van Millingen, Alexander (1912). Byzantine Churches of Constantinople. London: MacMillan & Co.

- Mathews, Thomas F. (1976). The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul: A Photographic Survey. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01210-2.

- Gülersoy, Çelik (1976). A guide to Istanbul. Istanbul: Istanbul Kitaplığı. OCLC 3849706.

- Müller-Wiener, Wolfgang (1977). Bildlexikon Zur Topographie Istanbuls: Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, Istanbul Bis Zum Beginn D. 17 Jh (in German). Tübingen: Wasmuth. ISBN 978-3-8030-1022-3.

- Krautheimer, Richard (1986). Architettura paleocristiana e bizantina (in Italian). Turin: Einaudi. ISBN 88-06-59261-0.

- Jacobi, David (2001). "The urban evolution of Latin Constantinople". In Necipoğlu, Nevra. Byzantine Constantinople: Monuments, Topography and everyday Life. Leiden, Boston, Köln: Brill. ISBN 90-04-11625-7.

- Asutay-Effenberger, Neslihan; Effenberger, Arne (2008). "Eski İmaret Camii, Bonoszisterne und Konstantinsmauer". Jahrbuch der österreichischen Byzantinistik (in German). 58: 13–44. ISBN 978-3-7001-6132-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eski Imaret Mosque. |