Chrematistics

Chrematistics (from Greek: χρηματιστική) (or the art of getting rich, as coined by Thales of Miletus) has historically had varying levels of acceptability in Western culture. This article will summarize historical trends.

Ancient Greece

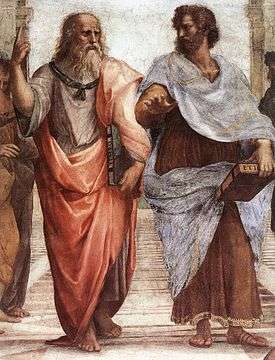

Aristotle established a difference between economics and chrematistics that would be foundational in medieval thought.[1] For Aristotle, the accumulation of money itself is an unnatural activity that dehumanizes those who practice it. Trade Exchanges, money for goods, and usury creates money from money, but do not produce useful goods. Hence, Aristotle, like Plato, condemns these actions from the standpoint of their philosophical ethics.[2]

According to Aristotle, the "necessary" chrematistic economy is licit if the sale of goods is made directly between the producer and buyer at the right price; it does not generate a value-added product. By contrast, it is illicit if the producer purchases for resale to consumers for a higher price, generating added value. The money must be only a medium of exchange and measure of value.[3]

Middle Ages

The Catholic Church maintained this economic doctrine throughout the Middle Ages.[4] Saint Thomas Aquinas accepted capital accumulation if it served for virtuous purposes as charity.

Modern

Although Martin Luther raged against usury and extortion, modern sociologists have argued that he inspired doctrines that assisted in the spread of capitalistic practices in early modern Europe. Max Weber argued that Protestant sects emphasized frugality, sobriety, deferred consumption, and saving.[5]

In Karl Marx's Das Kapital, Marx developed a labor theory of value inspired by Aristotle's notions of exchange.[6]

Further reading

- Aktouf, O. (1989): “Corporate Culture, the Catholic Ethic, and the Spirit of Capitalism: A Quebec Experience”, in Journal of Standing Conference on Organizational Symbolism. Istambul, pp. 43–80.

- Browdie, S.; Rowe, C. (2002): Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics: Translation, Introduction, and Commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Daly, H. and COBB, J. (1984): 'For the Common Good: Redirecting the Economy toward Community, the Environment, and a Sustainable Future'. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Kraut, R. (ed.) (2006): The Blackwell Guide to Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. Oxford: Blackwell.

- McLellan, D. (ed.) (2008): Capital (Karl Marx): An Abridged Edition. Oxford: Oxford Paperbacks; Abridged edition.

- Pakaluk, M. (2005): Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics: An Introduction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Schefold, B. (2002): “Reflections on the Past and Current State of the History of Economic Thought in Germany”, in History of Political Economy 34, Annual Supplement, pp. 125–136.

- Shipside, S. (2009): Karl Marx's Das Kapital: A Modern-day Interpretation of a True Classic. Oxford: Infinite Ideas.

- Tanner, S.J. (2001): The Councils of the Church. A Short History. New York: The Crossroad Publishing Company.

- Warne, C. (2007): Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics: Reader's Guide. London: Continuum.

References

- ↑ von Reden, Sitta. "Chrematistike". In Cancik, Hubert; Schneider, Helmuth; Landfester, Manfred; Salazar, Christine F.; Gentry, Francis G. Brill's New Pauly. J. B. Metzler Verlag. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ↑ Murray, Andrew (28 April 2010). Borkowski, Peter S.; Hurst, Dena; Jasso, Sean, eds. "Aristotle and Locke on the Moral Limits of Wealth" (E-journal). Philosophy for Business. University of Sheffield (59). Section 3. ISSN 2043-0736. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ↑ Aristotle, Politics, translated by Jowett, Benjamin, I.1257a-1258a

- ↑ "Second Lateran Council (1139 A.D.)". Papal Encyclicals Online. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ↑ Weber, Max (1992). The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Translated by Parsons, Talcott. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25559-7.

- ↑ Marx, Karl (1903). Engels, Frederick, ed. Das Kapital [Capital: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production]. Translated by Moore, Samuel; Aveling, Edward (3rd German ed.). S. Sonnenschein. pp. 28–29.