Choir

A choir (/ˈkwaɪ.ər/) (also known as a chorale or chorus) is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform. Choirs may perform music from the classical music repertoire, which spans from the Medieval era to the present, and/or popular music repertoire. Most choirs are led by a conductor, who leads the performances with arm and face gestures.

A body of singers who perform together as a group is called a choir or chorus. The former term is very often applied to groups affiliated with a church (whether or not they actually occupy the choir) and the second to groups that perform in theatres or concert halls, but this distinction is far from rigid. Choirs may sing without instrumental accompaniment, with the accompaniment of a piano or pipe organ, with a small ensemble (e.g., harpsichord, cello and double bass for a Baroque era piece), or with a full orchestra of 70 to 100 musicians.

The term "Choir" has the secondary definition of a subset of an ensemble; thus one speaks of the "woodwind choir" of an orchestra, or different "choirs" of voices and/or instruments in a polychoral composition. In typical 18th- to 21st-century oratorios and masses, chorus or choir is usually understood to imply more than one singer per part, in contrast to the quartet of soloists also featured in these works.

Structure

Choirs are often led by a conductor or choirmaster. Most often choirs consist of four sections intended to sing in four part harmony, but there is no limit to the number of possible parts as long as there is a singer available to sing the part: Thomas Tallis wrote a 40-part motet entitled Spem in alium, for eight choirs of five parts each; Krzysztof Penderecki's Stabat Mater is for three choirs of 16 voices each, a total of 48 parts. Other than four, the most common number of parts are three, five, six, and eight.

Choirs can sing with or without instrumental accompaniment. Singing without accompaniment is called a cappella singing (although the American Choral Directors Association[1] discourages this usage in favor of "unaccompanied," since a cappella denotes singing "as in the chapel" and much unaccompanied music today is secular). Accompanying instruments vary widely, from only one instrument (a piano or pipe organ) to a full orchestra of 70 to 100 musicians; for rehearsals a piano or organ accompaniment is often used, even if a different instrumentation is planned for performance, or if the choir is rehearsing unaccompanied music.

Many choirs perform in one or many locations such as a church, opera house, or school hall. In some cases choirs join up to become one "mass" choir that performs for a special concert. In this case they provide a series of songs or musical works to celebrate and provide entertainment to others.

Role of conductor

Conducting is the art of directing a musical performance, such as a choral concert, by way of visible gestures with the hands, arms, face and head. The primary duties of the conductor or choirmaster are to unify performers, set the tempo, execute clear preparations and beats (meter), and to listen critically and shape the sound of the ensemble.[2]

The conductor or choral director typically stands on a raised platform and he or she may or may not use a baton (using a baton creates more visible gestures. Many choral conductors use their hands to conduct. In the 2010s, most conductors do not play an instrument when conducting, although in earlier periods of classical music history, leading an ensemble while playing an instrument was common. In Baroque music from the 1600s to the 1750s, conductors performing in the 2010s may lead an ensemble while playing a harpsichord or the violin (see Concertmaster). Conducting while playing a piano may also be done with musical theatre pit orchestras. Communication is typically non-verbal during a performance (this is strictly the case in art music, but in jazz big bands or large pop ensembles, there may be occasional spoken instructions). However, in rehearsals, frequent interruptions allow the conductor to give verbal directions as to how the music should be sung.

Conductors act as guides to the choirs they conduct. They choose the works to be performed and study their scores, to which they may make certain adjustments (e.g., regarding tempo, repetitions of sections, assignment of vocal solos and so on), work out their interpretation, and relay their vision to the singers. Choral conductors may also have to conduct instrumental ensembles such as orchestras if the choir is singing a piece for choir and orchestra. They may also attend to organizational matters, such as scheduling rehearsals,[3] planning a concert season, hearing auditions, and promoting their ensemble in the media.

In worship services

Accompaniment

Eastern Orthodox churches, some American Protestant groups, and traditional synagogues do not use instruments. In churches of the Western Rite the accompanying instrument is usually the organ, although in colonial America, the Moravian Church used groups of strings and winds. Many churches which use a contemporary worship format use a small amplified band to accompany the singing, and Roman Catholic Churches may use, at their discretion, additional orchestral accompaniment.

Liturgical function

In addition to leading of singing in which the congregation participates, such as hymns and service music, some church choirs still sing full liturgies, including propers (introit, gradual, communion antiphons appropriate for the different times of the liturgical year). Chief among these are the Anglican and Roman Catholic churches; far more common however is the performance of anthems or motets at designated times in the service.

Types

- Mixed choirs (with male and female voices). This is perhaps the most common type, usually consisting of soprano, alto, tenor, and bass voices, often abbreviated as SATB. Often one or more voices is divided into two, e.g., SSAATTBB, where each voice is divided into two parts, and SATBSATB, where the choir is divided into two semi-independent four-part choirs. Occasionally baritone voice is also used (e.g., SATBarB), often sung by the higher basses. In smaller choirs with fewer men, SAB, or Soprano, Alto, and Baritone arrangements allow the few men to share the role of both the tenor and bass in a single part.

- Male choirs, with the same SATB voicing as mixed choirs, but with boys singing the upper part (often called trebles or boy sopranos) and men singing alto (in falsetto), also known as countertenors. This format is typical of the British cathedral choir. (Peterborough, St Paul's, Westminster abbey)

- Female choirs, usually consisting of soprano and alto voices, two parts in each, often abbreviated as SSAA, or as soprano I, soprano II, and alto, abbreviated SSA.

- Men's choirs, or Male Chorale, usually consisting of two tenors, baritone, and bass, often abbreviated as TTBB (or ATBB if the upper part sings falsetto in alto range). ATBB may be seen in some barbershop quartet music.

- Children's choirs, often two-part SA or three-part SSA, sometimes more voices. This includes boy choirs.Boy choirs typically sing SSA or SSAA, sometimes including a tenor part for boys whose voices are changing.

- Indian music choral group, takes the elements of western music in Indian music. Madras Youth choir is a pioneer in this.

Choirs are also categorized by the institutions in which they operate:

- Church (including cathedral) choirs

- Collegiate and university choirs

- Community choirs (of children or adults)

- Professional choirs, either independent (e.g. Anúna) or state-supported (e.g., BBC Singers, National Chamber Choir of Ireland, Canadian Chamber Choir, Swedish Radio Choir, Nederlands Kamerkoor)

- School choirs

- Signing choirs using sign language rather than voices

- Integrated signing and singing choirs, using both sign language and voices and led by both a signductor and a musical director

- Cambiata choirs, often the same SATB, but with girls singing soprano and alto, along with trebles and cambiatas and boy altos

Some choirs are categorized by the type of music they perform, such as

- Bach choirs

- Barbershop music

- Gospel choirs

- Show choirs, in which the members sing and dance, often in performances somewhat like musicals

- Symphonic choirs

- Vocal jazz choirs

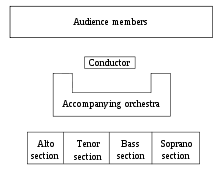

Arrangements on stage

There are various schools of thought regarding how the various sections should be arranged on stage. (It is the conductor's decision on where the different voice types are placed)

In symphonic choirs it is common (though by no means universal) to order the choir behind the orchestra from highest to lowest voices from left to right, corresponding to the typical string layout.

In a cappella or piano-accompanied situations it is not unusual for the men to be in the back and the women in front; some conductors prefer to place the basses behind the sopranos, arguing that the outer voices need to tune to each other.

More experienced choirs may sing with the voices all mixed. Sometimes singers of the same voice are grouped in pairs or threes. Proponents of this method argue that it makes it easier for each individual singer to hear and tune to the other parts, but it requires more independence from each singer. Opponents argue that this method loses the spatial separation of individual voice lines, an otherwise valuable feature for the audience, and that it eliminates sectional resonance, which lessens the effective volume of the chorus.

For music with double (or multiple) choirs, usually the members of each choir are together, sometimes significantly separated, especially in performances of 16th-century music. Some composers actually specify that choirs should be separated, such as in Benjamin Britten's War Requiem.

Consideration is also given to the spacing of the singers. Studies have found that not only the actual formation, but the amount of space (both laterally and circumambiently) affects the perception of sound by choristers and auditors.[4]

Historical overview of choral music

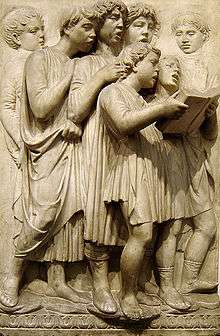

Antiquity

The origins of choral music are found in traditional music, as singing in big groups is extremely widely spread in traditional cultures (both singing in one part, or in unison, like in Ancient Greece, as well as singing in parts, or in harmony, like in contemporary European choral music).[5]

The oldest unambiguously choral repertory that survives is that of ancient Greece, of which the 2nd century BC Delphic hymns and the 2nd century AD. hymns of Mesomedes are the most complete. The original Greek chorus sang its part in Greek drama, and fragments of works by Euripides (Orestes) and Sophocles (Ajax) are known from papyri. The Seikilos epitaph (2c BC) is a complete song (although possibly for solo voice). One of the latest examples, Oxyrhynchus hymn (3c) is also of interest as the earliest Christian music.

Of the Roman drama's music a single line of Terence surfaced in the 18c. However, musicologist Thomas J. Mathiesen comments that it is no longer believed to be authentic.[6]

Medieval music

The earliest notated music of western Europe is Gregorian chant, along with a few other types of chant which were later subsumed (or sometimes suppressed) by the Catholic Church. This tradition of unison choir singing lasted from sometime between the times of St. Ambrose (4th century) and Gregory the Great (6th century) up to the present. During the later Middle Ages, a new type of singing involving multiple melodic parts, called organum, became predominant for certain functions, but initially this polyphony was only sung by soloists. Further developments of this technique included clausulae, conductus and the motet (most notably the isorhythmic motet), which, unlike the Renaissance motet, describes a composition with different texts sung simultaneously in different voices. The first evidence of polyphony with more than one singer per part comes in the Old Hall Manuscript (1420, though containing music from the late 14th century), in which there are apparent divisi, one part dividing into two simultaneously sounding notes.

Renaissance music

During the Renaissance, sacred choral music was the principal type of formally notated music in Western Europe. Throughout the era, hundreds of masses and motets (as well as various other forms) were composed for a cappella choir, though there is some dispute over the role of instruments during certain periods and in certain areas. Some of the better-known composers of this time include Guillaume Dufay, Josquin des Prez, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, John Dunstable, and William Byrd; the glories of Renaissance polyphony were choral, sung by choirs of great skill and distinction all over Europe. Choral music from this period continues to be popular with[7] many choirs throughout the world today.

The madrigal, a partsong conceived for amateurs to sing in a chamber setting, originated at this period. Although madrigals were initially dramatic settings of unrequited-love poetry or mythological stories in Italy, they were imported into England and merged with the more dancelike balletto, celebrating carefree songs of the seasons, or eating and drinking. To most English speakers, the word madrigal now refers to the latter, rather than to madrigals proper, which refers to a poetic form of lines consisting of seven and eleven syllables each.

The interaction of sung voices in Renaissance polyphony influenced Western music for centuries. Composers are routinely trained in the "Palestrina style" to this day, especially as codified by the 18c music theorist Johann Joseph Fux. Composers of the early 20th century also wrote in Renaissance-inspired styles. Herbert Howells wrote a Mass in the Dorian mode entirely in strict Renaissance style, and Ralph Vaughan Williams's Mass in G minor is an extension of this style. Anton von Webern wrote his dissertation on the Choralis Constantinus of Heinrich Isaac and the contrapuntal techniques of his serial music may be informed by this study.

Baroque music

The Baroque period in music is associated with the development around 1600 of the figured bass, with dramatic implications in the realm of solo vocal music such as the monodies of the Florentine Camerata and opera. This innovation was in fact an extension of established practice of accompanying choral music at the organ, either from a skeletal reduced score (from which otherwise lost pieces can sometimes be reconstructed) or from a basso seguente, a part on a single staff containing the lowest sounding part.

A new genre was the vocal concertato, combining voices and instruments; its origins may be sought in the polychoral music of the Venetian school. Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643) brought it to perfection with his Vespers and his Eighth Book of Madrigals,[8] which call for great virtuosity on the part of singers and instruments alike. His pupil Heinrich Schütz (1585–1672) (who had earlier studied with Giovanni Gabrieli) introduced the new style to Germany. Alongside the new music of the seconda pratica, contrapuntal motets in the stile antico or old style continued to be written well into the 19th century.

It should be remembered that choirs at this time were usually quite small and that singers could be classified as suited to church or to chamber singing. Monteverdi, himself a singer, is documented as taking part in performances of his Magnificat with one voice per part.[9]

Independent instrumental accompaniment opened up new possibilities for choral music. Verse anthems alternated accompanied solos with choral sections; the best-known composers of this genre were Orlando Gibbons and Henry Purcell. Grands motets (such as those of Lully and Delalande) separated these sections into separate movements. Oratorio, pioneered by Giacomo Carissimi, extended this concept into concert-length works, usually loosely based on Biblical stories.

The pinnacle of the oratorio is found in George Frideric Handel's works, notably Messiah and Israel in Egypt. While the modern chorus of hundreds had to await the growth of Choral Societies and his centennial commemoration concert, we find Handel already using a variety of performing forces, from the soloists of the Chandos Anthems to larger groups (whose proportions are still quite different from modern orchestra choruses):

Yesterday [Oct. 6] there was a Rehearsal of the Coronation Anthem in Wesminster-Abby, set to musick by the famous Mr Hendall: there being 40 voices, and about 160 violins, Trumpets, Hautboys, Kettle-Drums and Bass' proportionable..!— Norwich Gazette, October 14, 1727

Lutheran composers wrote instrumentally accompanied cantatas, often based on chorale tunes. While Dieterich Buxtehude was a significant composer of such works, it was largely up to the next generation to undertake cantata cycles on texts for the entire church year. Georg Philipp Telemann wrote choral cantatas for Frankfurt (later published in solo versions as the Harmonische Gottesdienst) and Graupner cycles for Darmstadt, but Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) made a truly monumental contribution: his obituary mentions five complete cycles of his cantatas, of which three, comprising some 200 works, are known today, in addition to motets. Bach himself rarely used the term cantata. Motet refers to his church music without orchestra accompaniment, but instruments playing colla parte with the voices. His works with accompaniment consists of his Passions, Masses, the Magnificat and the cantatas.

A point of hot controversy today is the so-called "Rifkin hypothesis," which re-examines the famous "Entwurff" Bach's 1730 memo to the Leipzig City Council (A Short but Most Necessary Draft for a Well Appointed Church Music) calling for at least 12 singers. In light of Bach's responsibility to provide music to four churches and be able to perform double choir compositions with a substitute for each voice, Joshua Rifkin concludes that Bach's music was normally written with one voice per part in mind. A few sets of original performing parts include ripieni who reinforce rather than slavishly double the vocal quartet.

|

Hallelujah Chorus

The Hallelujah Chorus, from George Frideric Handel's Messiah, is one of the most famous choruses of all time |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Classical and Romantic music

Composers of the late 18th century became fascinated with the new possibilities of the symphony and other instrumental music, and generally neglected choral music. Mozart's choral works, though not as numerous as his works for other media, stand out as some of his greatest (such as the "Great" Mass in C minor and Requiem in D minor, the latter of which is often considered the greatest Requiem Mass of all time). Haydn became more interested in choral music near the end of his life following his visits to England in the 1790s, when he heard various Handel oratorios performed by large forces; he wrote a series of masses beginning in 1797 and his two great oratorios The Creation and The Seasons. Beethoven wrote only two masses, both intended for liturgical use, although his Missa solemnis is suitable only for the grandest ceremonies. He also pioneered the use of chorus as part of symphonic texture with his Ninth Symphony and Choral Fantasia.

In the 19th century, sacred music escaped from the church and leaped onto the concert stage, with large sacred works unsuitable for church use, such as Berlioz's Te Deum and Requiem, and Brahms's Ein deutsches Requiem. Rossini's Stabat mater, Schubert's masses, and Verdi's Requiem also exploited the grandeur offered by instrumental accompaniment.

Oratorios also continued to be written, clearly influenced by Handel's models. Berlioz's L'enfance du Christ and Mendelssohn's Elijah and St Paul are in the category. Schubert, Mendelssohn, and Brahms also wrote secular cantatas, the best known of which are Brahms's Schicksalslied and Nänie.

A few composers developed a cappella music, especially Bruckner, whose masses and motets startlingly juxtapose Renaissance counterpoint with chromatic harmony. Mendelssohn and Brahms also wrote significant a cappella motets.

The amateur chorus (beginning chiefly as a social outlet) began to receive serious consideration as a compositional venue for the part-songs of Schubert, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Brahms, and others. These 'singing clubs' were often for women or men separately, and the music was typically in four-part (hence the name "part-song") and either a cappella or with simple instrumentation. At the same time, the Cecilian movement attempted a restoration of the pure Renaissance style in Catholic churches.

|

"Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen"

(How lovely is thy dwelling place) from Ein deutsches Requiem by Johannes Brahms |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

20th and 21st centuries

As in other genres of music, choral music underwent a period of experimentation and development during the 20th century. While few well-known composers focused primarily on choral music, most significant composers of the early century produced some fine examples that have entered the repertoire.

The early modernist composers, such as Richard Strauss, Sergei Rachmaninoff and Max Reger contributed to the genre. Ralph Vaughan Williams's Mass in G minor harks back to the Renaissance style while exhibiting the vibrancy of new harmonic languages. Vaughan Williams also arranged English and Scottish folk songs. Arnold Schoenberg's Friede auf Erden is a tonal kaleidoscope, whose tonal centers are constantly shifting (his harmonically innovative Verklärte Nacht for strings dates from the same period). Ukrainian composer Mykola Leontovych also explored new ways of harmonizing and arranging Ukrainian folk songs, producing masterpieces such as Dudaryk and Shchedryk, the latter of which featured a four-note ostinato theme and became a popular Christmas carol known as Carol of the Bells after it was translated by Peter J. Wilhousky.

The advent of atonality and other non-traditional harmonic systems and techniques in the 20th century also affected choral music. Serial music is represented by choral works by Arnold Schoenberg, including the anthem "Dreimal Tausend Jahre," while the composer's signature use of sprechstimme is evident in his psalm "De Profundis." Paul Hindemith's distinctive modal language is represented by both his a cappella Mass and his Six Chansons on texts by Rilke, while a more contrapuntally dissonant style comes through in his secular requiem, When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd. Olivier Messiaen also demonstrates dissonant counterpoint in his Cinq Rechants, which tell the Tristan and Isolde story. Charles Ives' psalm settings exemplify the composer's incomparably radical harmonic language. Tone clusters and aleatory elements play a prominent role in the choral music of Krzysztof Penderecki, who wrote the St. Luke Passio, and György Ligeti, who wrote both a Requiem and a separate Lux Aeterna. Milton Babbitt incorporated integral serialism into works for children's chorus, while Daniel Pinkham wrote for choir and electronic tape. Meredith Monk's Panda Chant and Astronaut Anthem explore overtones in an unconventional text setting. Though difficult and rarely performed by amateurs, pieces that demonstrate such unfamiliar idioms have found their way into the repertories of the finest semi-professional and professional choirs around the world.

More accessible styles of choral music include that by Benjamin Britten, including his War Requiem, Five Flower Songs, and Rejoice in the Lamb. Francis Poulenc's Motets pour le temps de noël, Gloria, and Mass in G are often performed. A primitivist approach is exemplified by Carl Orff's widely performed Carmina Burana. In the United States, Aaron Copland, Samuel Barber, and Randall Thompson wrote signature American pieces. In Eastern Europe, Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály wrote a small amount of music for choirs. Frank Martin's Mass for double choir combines modality and allusion to Medieval and Renaissance forms with a distinctly modern harmonic language and has become the composer's most performed work.

The so-called holy minimalists are represented by Arvo Pärt, whose Johannespassion and Magnificat have received regular performances; John Tavener (Song for Athene) and Henryk Górecki (Totus Tuus) share this label. American minimalism and post minimalism are represented by Steve Reich's The Desert Music, choral excerpts from Philip Glass's Einstein on the Beach and John Adams' The Death of Klinghoffer, and David Lang's Pulitzer Prize-winning Little Match Girl Passion.

.jpg)

At the turn of the 21st century, choral music has received a resurgence of interest partly due to a renewed interest in accessible choral idioms. Multi-cultural influences are found in Osvaldo Golijov's St. Mark Passion, which melds the Bach-style passion form with Latin American street music, and Chen Yi's Chinese Myths Cantata melds atonal idioms with traditional Chinese melodies played on traditional Chinese instruments. Some composers began to earn their reputation based foremost on their choral output, including the highly popular John Rutter and Eric Whitacre. The large scale dramatic works of Karl Jenkins seem to hearken back to the theatricality of Orff, and the music of James MacMillan continues the tradition of boundary-pushing choral works from the United Kingdom begun by Britten, Walton, and Leighton. Meanwhile, composers such as John Williams, known primarily for film scores, and prominent concert orchestral composers such as Augusta Read Thomas, Sofia Gubaidulina, Aaron Jay Kernis, and Thomas Adès also contribute vital additions to the choral repertoire.

A number of traditions originating outside of classical concert music have enriched the choral repertoire as well as provided new outlets to composers:

- At the end of the 19th century, male voice choirs became popular with the coal miners of South Wales, and numerous choirs were established including the Treorchy Male Choir, Morriston Orpheus Choir and Cor Meibion Pontypridd male voice choirs. Although the mining communities which gave rise to these choirs largely died out in the 1970s and 1980s with the decline of the Welsh coal industry, many of these choirs continue, and are seen as a traditional part of Welsh culture and perform worldwide. Not all of the choirs were based on coal – some started in the rugby clubs, such as Cardiff Arms Park Male Choir and Morriston Rugby Choir, while others such as Pontarddulais Male Choir were formed out of a youth choir.

- Black Spirituals entered the concert repertoire with the tours of the Fisk College Jubilee Singers, and arrangements of such spirituals are now part of the standard choral repertoire. Notable composers and arrangers of choral music in this tradition include William Dawson, Jester Hairston and Moses Hogan.

- During the mid 20th century, barbershop quartets began experimenting with combining larger ensembles together into choruses which sing barbershop music in 4 parts, often with staging, choreography and costumes. The first international barbershop chorus contest was held in 1953 and continues to this day.

- Contemporary choirs, such as Rock Choir and London Contemporary Voices in the United Kingdom, have become popular since the beginning of the 21st century. They usually perform rock, pop, soul and Motown songs in close-part vocal harmony, often incorporating dance moves.

See also

- Carol (music), a festive song or hymn often sung by a choir or a few singers with or without instrumental accompaniment

- Come and sing

References

- ↑ See "Choral Reviews Format" on ACDA.org

- ↑ Michael Kennedy; Joyce Bourne Kennedy (2007). Oxford Concise Dictionary of Music (Fifth ed.). Oxford University Press, Oxford. ISBN 9780199203833.

Conducting

- ↑ About.com: The Conductor at the Wayback Machine (archived April 15, 2013)

- ↑ Daugherty, J. "Spacing, Formation, and Choral Sound: Preferences and Perceptions of Auditors and Choristers." Journal of Research in Music Education. Vol. 47, Num. 3. 1999.

- ↑ Joseph Jordania. 2011. Why do People Sing? Music in Human Evolution. Logos

- ↑ Warren Anderson and Thomas J. Mathiesen. "Terence", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. S. Sadie and J. Tyrrell (London: Macmillan, 2001), xxv, 296.

- ↑ Bent, Margaret. ""Dunstaple, John"". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ His Fifth Book includes a basso continuo "for harpsichord or lute".

- ↑ Richard Wistreich: "'La voce e grata assai, ma..' Monteverdi on Singing" in Early Music, February 1994–

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Choirs. |

| Look up chorus, chorale, or choir in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Databases

- Choral Public Domain Library

- Musica International – choral repertoire database

- Global Chant Database – Gregorian and plainchant

Professional organizations

- International Federation for Choral Music

- European Choral Association/Europa Cantat (Europe)

- The Association of Gaelic Choirs (Scotland)

- Association of British Choral Directors(UK)

- National Association of Choirs (UK)

- Chorus America (North America)

- Association of Canadian Choral Communities (Canada)

- American Choral Directors Association (US)

- Brazilian Choral Organization (Brazil)

Resources

- ChoralNet

- Gerontius (UK)

- The Boy Choir & Soloist Directory

- Singers.com

- Vocal Area Network

- GALA Choruses (GLBT chorus association)

- ChoirPlace (international choir network)

- Singing Europe (Pilot research on Collective singing in Europe)

Media

- Choral Music from Classical MPR, online choral music radio stream

- Sacred Classics, weekly choral music radio program

Reading

- Page, Anne, B mus. "Of Choristers – ancient and modern, A history of cathedral choir schools". ofchoristers.net.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Choir". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 260–261.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Choir". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 260–261. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Chorus". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Chorus". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.