Infection in childcare

Infection in childcare is the spread of infection during childcare, typically because of contact among children in daycare or school. This happens when groups of children meet in a childcare environment, and there any individual with an infectious disease may spread it to the entire group. Commonly spread diseases include influenza-like illness and enteric illnesses, such as diarrhea among babies using diapers. It is uncertain how these diseases spread, but hand washing reduces some risk of transmission and increasing hygiene in other ways also reduces risk of infection.

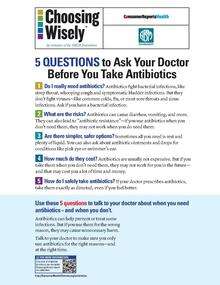

Due to social pressure, parents of sick children in childcare may be willing to give unnecessary medical care to their children when advised to do so by childcare workers and even if it is against the advice of health care providers. In particular, children in childcare are more likely to be given antibiotics than children outside of childcare.

Mechanism of transmission

The presumption behind the idea of a "childcare infection" is that a place in which many children come into contact with each other can be a focus of infection, which is a place where infections are able to spread from person to person.

Flu and respiratory tract infection are lessened in groups which use frequent hand washing, but the actual pathway through which the diseases spread is unclear except for the fact that hand washing disrupts disease transmission.[1]

Diseases related to the human gastrointestinal tract, like diarrhea or other enteric illness, often spread through the fecal-oral route and are especially common in places where children have not completed toilet training.[2] Diapers, confined spaces for changing diapers, and the unhygienic habits of children contribute to the spread of these infections.[2] Bacterial infections most often spread through person to person contact, while eating food, or through the presence of animals.[2] It is difficult to determine how viral agents causing enteric illness spread.[2] Reviews of Helicobacter pylori have been unable to determine how it spreads during childcare, but have confirmed that it does easily spread in childcare environments, and that it is difficult to make recommendations for preventing it.[3]

Epidemiology

Childcare infection is a public health concern because it harms the health of individual children and the infections which children get during childcare also may be spread within their homes and communities away from the childcare.[4] Generally, children who attend childcare are 2-3 times more likely to acquire an infection than children who do not use such services.[4]

Prevention

Infection happens because of individuals bringing infections into a childcare environment and spreading infectious agents within that environment, which children then contact and become at risk for infection. Increased risk of infection is related to practices of those in the childcare environment, and infection risk can be reduced by taking precautions.[4] Practices which reduce the likelihood of spreading infection include encouraging hand washing in all present, providing facial tissue to cover sneezes, doing food preparation in a place separate from other activity, cleaning and using a disinfectant on surfaces people touch, and among groups using diapers, having good practices to change and dispose of diapers while cleaning children and the changing area.[4]

Treatment

Childcare infections can be treated just as infections acquired outside of childcare, however, there are pressures on sick children to begin taking unnecessary health care even against the advice of health care providers. Antibiotics are commonly given to children for whom the drugs would serve no benefit, due to the child not having a medical condition which antibiotics can treat.[5] This is especially common in children with respiratory infections which antibiotics cannot treat, and in younger children, and in children who have privately purchased health insurance covering their medical expenses.[5]

Children who attend childcare are twice as likely to take an antibiotic when sick as children who do not attend childcare.[6] This is because child care providers wish to host children who are not sick, and consequently pressure parents to seek antibiotics or other treatment even when it is against the advice of health care providers.[6] In turn, parents feel compelled to seek this treatment for their children to please the care providers even if it is against the advice of their health care provider.[6] Overuse of antibiotics in child care has led to an increase of antibiotic resistance in bacteria in childcare settings.[7] While the increase of antibiotic resistance is worrisome, the current implications of this are uncertain, although it is expected that this will become more of a public health problem in the future.[7]

Society and culture

Families in which parents take time off work to care for their sick children instead of sending them to childcare services may be harmed by missing the loss of work hours and pay.[8] Some research has suggested that when parents have paid leave from work to tend to sick children then they are less likely to give their children antibiotics unless they are sure that it is recommended by a health care provider.[9]

Childcare providers often refuse to care for sick children, and ask that parents make alternate arrangements.[10] For various reasons including an inability of childcare providers to know which illnesses are infectious, childcare providers often refuse to care even for children who have acute illnesses which are unlikely spread to others.[10]

References

- ↑ Warren-Gash, C; Fragaszy, E; Hayward, AC (Sep 2013). "Hand hygiene to reduce community transmission of influenza and acute respiratory tract infection: a systematic review.". Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 7 (5): 738–49. doi:10.1111/irv.12015. PMID 23043518.

- 1 2 3 4 Lee, MB; Greig, JD (Oct 2008). "A review of enteric outbreaks in child care centers: effective infection control recommendations.". Journal of environmental health. 71 (3): 24–32, 46. PMID 18990930.

- ↑ Bastos, J; Carreira, H; La Vecchia, C; Lunet, N (Jul 2013). "Childcare attendance and Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis.". European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 22 (4): 311–9. doi:10.1097/cej.0b013e32835b69aa. PMID 23242007.

- 1 2 3 4 Nesti, MM; Goldbaum, M (Jul–Aug 2007). "Infectious diseases and daycare and preschool education.". Jornal de pediatria. 83 (4): 299–312. doi:10.2223/jped.1649. PMID 17632670.

- 1 2 Hersh, AL; Shapiro, DJ; Pavia, AT; Shah, SS (Dec 2011). "Antibiotic prescribing in ambulatory pediatrics in the United States.". Pediatrics. 128 (6): 1053–61. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-1337. PMID 22065263.

- 1 2 3 Rooshenas, L; Wood, F; Brookes-Howell, L; Evans, MR; Butler, CC (May 2014). "The influence of children's day care on antibiotic seeking: a mixed methods study.". The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 64 (622): e302–12. doi:10.3399/bjgp14x679741. PMID 24771845.

- 1 2 Holmes, SJ; Morrow, AL; Pickering, LK (1996). "Child-care practices: effects of social change on the epidemiology of infectious diseases and antibiotic resistance.". Epidemiologic reviews. 18 (1): 10–28. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017913. PMID 8877328.

- ↑ McCutcheon, H; Fitzgerald, M (May 2001). "The public health problem of acute respiratory illness in childcare.". Journal of clinical nursing. 10 (3): 305–10. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2702.2001.00486.x. PMID 11820539.

- ↑ Thrane, N; Olesen, C; Md, JT; Søndergaard, C; Schønheyder, HC; Sørensen, HT (May 2001). "Influence of day care attendance on the use of systemic antibiotics in 0- to 2-year-old children.". Pediatrics. 107 (5): E76. doi:10.1542/peds.107.5.e76. PMID 11331726.

- 1 2 Hashikawa, A. N.; Juhn, Y. J.; Nimmer, M.; Copeland, K.; Shun-Hwa, L.; Simpson, P.; Stevens, M. W.; Brousseau, D. C. (19 April 2010). "Unnecessary Child Care Exclusions in a State That Endorses National Exclusion Guidelines". Pediatrics. 125 (5): 1003–1009. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2283.

External links

- Day care health risks at MedLine Plus

- Respiratory Tract Infections in Children, a Merck Manual guide for patients and caregivers