Red Ruthenia

| Red Ruthenia Ruś Czerwona (Polish) Червона Русь (Ukrainian) | |

|---|---|

| Historic Region | |

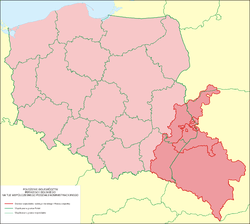

Red Ruthenia (without Podolia) on contemporary borders | |

| Region | Eastern Europe (Poland, Ukraine) |

Red Ruthenia, Red Rus or Red Russia (Latin: Ruthenia Rubra or Russia Rubra; Ukrainian: Червона Русь, Chervona Rus, Polish: Ruś Czerwona, Russian: Червоная Русь, Chervonaya Rus) is a historic term used since the Middle Ages for southeastern Poland and Western Ukraine.

First mentioned in a 1321 Polish chronicle, Red Ruthenia was the portion of Rus' incorporated into Poland by Casimir the Great during the 14th century.

From the 14th century, after the disintegration of Rus', Red Ruthenia was contested by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (the Gediminids), the Kingdom of Poland (the Piasts), the Kingdom of Hungary and the Kingdom of Ruthenia. After the Galicia–Volhynia Wars, for about 400 years most of Red Ruthenia became part of Poland as the Ruthenian Voivodeship. The historic Red Ruthenia, reaching Przemyśl and Sanok in the southwest, has been primarily inhabited for nearly a millennium by Ruthenians – a term which, in this context, refers to both ethnic Ukrainians and Rusyns.

Ethnicities

The first known inhabitants of Red Ruthenia were Lendians,[2] with Boykos and Lemkos on its perimeters. Later Walddeutsche, Jews, Armenians and Poles also made up part of the population.[3] According to Marcin Bielski, although Bolesław I Chrobry settled Germans in the region to defend the borders against Hungary and Kievan Rus' the settlers became farmers. Maciej Stryjkowski described German peasants near Rzeszów, Przemyśl, Sanok, and Jarosław as good farmers. Casimir the Great settled German citizens on the borders of Lesser Poland and Red Ruthenia to join the acquired territory with the rest of his kingdom. In determining the population of late medieval Poland, colonisation and Polish migration to Red Ruthenia, Spiš and Podlachia[4] (whom the Ukrainians called Mazury—poor peasant migrants, chiefly from Mazowsze[5]) should be considered.

During the second half of the 14th century, the Vlachs arrived from the southeastern Carpathians and quickly overspread southern Red Ruthenia. Although during the 15th century the Ruthenians gained a foothold, it was not until the 16th century that the Wallachian population in the Bieszczady Mountains and the Lower Beskids was Ruthenized.[6] From the 14th to the 16th centuries Red Ruthenia underwent rapid urbanization, resulting in over 200 new towns built on the German model (virtually unknown before 1340, when Red Ruthenia was the independent Duchy of Halych).[7]

Etymology

There are at least three theories concerning the origins of the name Red Ruthenia.

- A popular belief that it was derived from the traditional associations of particular colours with cardinal points of the compass. This originated with mythology of the pre-Christian god Svetovid, who had four faces: his northern face was white, the southern black, eastern green and the western red.

- However, critics of the above theory point out that Black Ruthenia is west of White Ruthenia, and in the case of Red Ruthenia, the name coincides with some Central Asian traditions regarding cardinal points, in which red represents "south" and black represents "north" (possibly reflecting the nomenclature of migrating Turkic or Mongol tribes).

- According to a third theory, many place names in Red Ruthenia start in cherv- (Черв-; czerw-), after Proto-Slavic *čьrvenъ "red". These include the so-called Cherven Cities.

History

During the Middle Ages, the region was part of the Ruthenian Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia. It came under Polish control in 1340, when Casimir the Great acquired it.[8][9] During his reign from 1333 to 1370, Casimir the Great founded several cities, urbanizing the rural province.[10]

The name Ruś Czerwona (translated as "Red Ruthenia") has been used for the territory extending to the Dniester, centring on Przemyśl (Peremyshl). Since the reign of Władysław Jagiełło the Przemyśl Voivodeship was called the Ruthenian Voivodeship (województwo ruskie), centring on Lwów. The voivodeship consisted of five regions: Lwów, Sanok, Halicz (Halych), Przemyśl (Peremyshl), and Chełm. The town of Halych gave its name to Galicia.

In October 1372, Władysław Opolczyk was deposed as count palatine. Although he retained most of his castles and goods in Hungary, his political influence waned. As compensation, Opolczyk was made governor of Hungarian Galicia. In this new position, he contributed to the economic development of the territories entrusted to him. Although Opolczyk primarily resided in Lwów, at the end of his rule he spent more time in Halicz. The only serious conflict during his time as governor involved his approach to the Russian Orthodox Church, which angered the local Catholic boyars. Under Polish rule 325 towns were founded from the 14th century to the second half of the 17th century, most during the 15th and 16th centuries (96 and 153, respectively).[11]

Red Ruthenia (except for Podolia) was conquered by the Austrian Empire in 1772 during the First Partition of Poland, remaining part of the empire until 1918.[12] Between World Wars I and II, it belonged to the Second Polish Republic. The region is currently split, with its western portion in southeastern Poland (around Rzeaszów, Przemyśl, Zamość and Chełm) and its eastern portion (around Lviv) in western Ukraine.

Administrative division (14th century to 1772)

During the 1340s, the influence of the Rurik dynasty ended; most of the area passed to Casimir the Great, with Kiev and the state of Volhynia falling under Lithuanian control. The Polish region was divided into a number of voivodeships, and an era of German eastward migration and Polish settlement among the Ruthenians began. Armenians and Jews also migrated to the region. A number of castles were built at this time, and the cities of Stanisławów (Stanyslaviv in Ukrainian, now Ivano-Frankivsk) and Krystynopol (now Chervonohrad) were founded. Ruthenia was subject to repeated Tatar and Ottoman Empire incursions during the 16th and 17th centuries and was impacted by the Khmelnytsky Uprising (1648–1654), the 1654–1667 Russo-Polish War and Swedish invasions during the Deluge (1655–1660); the Swedes returned during the Great Northern War of the early 18th century. Red Ruthenia consisted of three voivodeships: Ruthenia, whose capital was Lviv and provinces were Lviv, Halych, Sanok, Przemyśl and Chełm; Bełz, separating the provinces of Lviv and Przemyśl from the rest of the Ruthenian voivodeship; and Podolia, with its capital at Kamieniec Podolski.

Ruthenian Voivodeship

- Chełm Land (Ziemia Chełmska), Chełm

- Chełm County, (Powiat Chełmski), Chełm

- Powiat of Ratno, (Powiat Ratneński), Ratno

- Halicz Land (Ziemia Halicka), Halicz

- Lwów Land (Ziemia Lwowska), Lwów

- Powiat of Lwów, (Powiat Lwowski), Lwów

- Powiat of Żydaczów, (Powiat Żydaczowski), Żydaczów

- Przemyśl Land (Ziemia Przemyska), Przemyśl; Its area was 12,000 km2. and in the 17th century it was divided five smaller regions (county, powiaty).

- Przemyśl County (Powiat Przemyski), Przemyśl

- Powiat of Sambor, (Powiat Samborski), Sambor

- Powiat of Drohobycz, (Powiat Drohobycki), Drohobycz

- Powiat of Stryj, (Powiat Stryjski), Stryj

- Sanok Land (Ziemia Sanocka), Sanok

- Sanok County (Powiat Sanocki), Sanok: Intensive settlement occurred from the 13th to 15th centuries in an area flanked by the Wisłok, San and Wisłoka Rivers. The Vlachs primarily engaged in agriculture; moving west, they established a number of villages during the 15th century. In Sanok Land were six Jewish communities, with synagogues and kahal organizations. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Jewish Communities were also autonomous in criminal law.

Bełz Voivodeship

- Belz County, (Powiat Bełzski), Bełz

- Grabowiec County, (Powiat Grabowiecki), Grabowiec

- Horodło County, (Powiat Horodelski), Horodło

- Lubaczów County, (Powiat Lubaczowski), Lubaczów

- Busk Land, (Ziemia Buska), Busk

Bełz Voivodeship coat of arms |

Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia coat of arms[14] |

Sanok County coat of arms |

World War I and Polish-Ukrainian War

During World War I, Galicia (Red Ruthenia) saw heavy fighting between Russia and the Central Powers. Russian forces overran most of the region in 1914, after defeating the Austro-Hungarian army in a chaotic frontier battle during the war's opening months; this gave Russia the opportunity to invade Germany from the south. In 1918 western Ruthenia became part of the restored Republic of Poland, and the local Ukrainian population briefly declared independence fpr eastern Galicia as the West Ukrainian People's Republic. These competing claims lead to the Polish–Ukrainian War.

In western Red Ruthenia, Rusyn Lemkos formed the Lemko Republic in 1918 in an attempt to unite with Russian Soviet Republic instead of Ukraine. This proved impossible, and they later attempted to unite with Rusyns from south of the Carpathians to join Czechoslovakia as a third ethnic entity. This effort was suppressed by the Polish government in 1920; the area was incorporated into Poland, and the republican leaders were acquitted by the Polish government.

Unlike the contemporaneous Lemko Republic to its west, the Komancza Republic planned to unite with the West Ukrainian People's Republic in an independent Ukrainian state. Unification of the Komancza Republic and West Ukraine was suppressed by the Polish government as part of the Polish–Ukrainian War.

World War II

In 1939 the Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht approved Fall Weiss, detailing the invasion of Poland. According to the plan, Galician military brigades would act as a fifth column, attacking and demoralizing the Polish Army in the rear if Polish resistance was stronger than expected.[15] After September 17, 1939, all territory east of the San, Bug and Neman Rivers (approximating Red Ruthenia) was annexed by the USSR and divided into four oblasts (Lviv, Stanislav, Drohobych and Ternopil, the latter including portions of Volhynia) of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

In 1940–1941, Soviet authorities conducted four mass deportations from the eastern part of the Second Polish Republic inhabited by Ukrainians, Belarusians, Jews, Lithuanians, Russians, Germans, Czechs, Armenians and Poles. Approximately 335,000 Polish citizens were deported to Siberia, Kazakhstan and northeastern European Russia by the NKVD. According to General Vasily Khristoforov, director of the FSB archives in Moscow, 297,280 Polish citizens were deported in 1940.[16]

After June 22, 1941, although Sovietisation ended when Germany occupied eastern Ruthenia during Operation Barbarossa and formed the District of Galicia, the evacuating Soviets killed many prisoners awaiting deportation. Conflicts in Ruthenia and Volhynia between Poles and Ukrainians also intensified during this time, with skirmishes between the Polish Home Army (AK), the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), the Wehrmacht and Soviet partisans. These conflicts included massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia and revenge attacks on Ukrainians in Ruthenia. Many Ukrainian Galicians joined the UPA and supported its anti-Soviet and anti-Polish activities; others joined Germany in its fight against the USSR, forming the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Galician) commanded by German and Austrian officers Walter Schimana and Fritz Freitag.

After the war

The new Polish-Soviet border, with majority-Polish-speaking areas in the west and Ruthenian Ukrainians in the center and east, was recognized by the western Allies at the Yalta Conference. However, there were large minority populations on either side of the new frontier; in 1947's Operation Vistula, Polish Communist authorities moved about 200,000 ethnic Ukrainians to the former eastern territories of Germany.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Red Ruthenia. |

- Red Cities

- History of Ukraine

- History of Poland

- Ruthenia

- White Ruthenia

- Black Ruthenia

- Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast

- Slovak invasion of Poland (1939)

- Stanisławów Voivodeship

Sources

- "Monumenta Poloniae Historica"

- Akta grodzkie i ziemskie z archiwum ziemskiego. Lauda sejmikowe. Tom XXIII, XXIV, XXV.

- Słownik geograficzny Królestwa Polskiego (Digital edition)

- Lustracja województwa ruskiego, podolskiego i bełskiego, 1564-1565 Warszawa, (I) edition 2001, pages 289. ISBN 83-7181-193-4

- Lustracje dóbr królewskich XVI-XVIII wieku. Lustracja województwa ruskiego 1661—1665. Część III ziemie halicka i chełmska. Polska Akademia Nauk - Instytut Historii. 1976

- Lustracje województw ruskiego, podolskiego i bełskiego 1564 - 1565, wyd. K. Chłapowski, H. Żytkowicz, cz. 1, Warszawa - Łódź 1992

- Lustracja województwa ruskiego 1661-1665, cz. 1: Ziemia przemyska i sanocka, wyd. K. Arłamowski i W. Kaput, Wrocław-Warszawa-Kraków. 1970

- Aleksander Jabłonowski. Polska wieku XVI, t. VII, Ruś Czerwona, Warszawa 1901 i 1903.

References

- ↑ „Karte von Germania, Kleinpolen, Hungary, Walachai u. Siebenbuergen nebst Theilen der angraenzenden Laender“ von des „Claudii Ptolemaei geographicae enarrationis libri octo“, 1525, Strassburg

- ↑ Andrzej Rozwałka (2008). "Pobuże region as an object of research and protection of the archaeological heritage from the period of Early Middle Ages". In Maciej St. Zięba. Our Bug. Creating conditions for development of the border areas of Poland, Ukraine and Belarus through enhancement and preservation of natural and cultural heritage (PDF). John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin. p. 109.

The cultural unity of the area had been disturbed, if we look at it from the perspective of the whole Smaller Poland, after the basin of upper and middle Bug and of upper Wieprz rivers had been taken over in 981 (or 979) by Ruthenia, with its rich culture of urban character, the fact that can be seen in such places as Czermno, Chełm, or Gródek on Bug . This way a new boundary had divided the former community of Lendians living in the basins of rivers San, upper Bug, Styr and probably upper Dniester, who subsequently were absorbed in majority by the eastern Slavic element.

- ↑ "were mainly Germans, Poles, Armenians and Jews, but also Karaims, Tatars, Greeks or Wallachians [in:] "Kwartalnik historii kultury materialnej: t. 47, PAN. 1999. p. 146

- ↑ Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte, 1992

- ↑ M. H. Marunchak. The Ukrainian Canadians, 1982

- ↑ Czajkowski, 1992; Parczewski, 1992; Reinfuss, 1948, 1987, 1990

- ↑ Kwartalnik historii kultury materialnej: t. 47, PAN. 1999. p. 146

- ↑ H. H. Fisher, "America and the New Poland (1928)", Read Books, 2007, p. 15

- ↑ N. Davies, God's playground: a history of Poland in two volumes, Oxford University Press, 2005, pp. 71, 135

- ↑ Anna Beredecka, NOWE LOKACJE MIAST KRÓLEWSKICH W MAŁOPOLSCE W LATACH 1333–1370

- ↑ A. Janeczek, Town and country in the Polish Commonwealth, 1350-1650, in: S. R. Epstein, Town and Country in Europe, 1300-1800, Cambridge University Press, 2004, p. 164

- ↑ K. Kocsis, E. K. Hodosi, Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin, Simon Publications, 1988, p. 84

- ↑ Franciszek Kotula. Pochodzenie domów przysłupowych w Rzeszowskiem. "Kwartalnik Historii Kultury Materialnej" Jahr. V., Nr. 3/4, 1957, S. 557

- ↑ "Lew wspięty w koronie, herb najważniejszego nabytku terytorialnego Kazimierza Wielkiego — Rusi Czerwonej, wywodzi się od poświadczonego już w drugiej dekadzie XIV w. godła napieczętnego książąt halicko-włodzimierskich Andrzeja i Lwa." [in:] Polskie herby ziemskie: geneza, treści, funkcje. 1 93. p. 14

- ↑ Sergei Berets. Ukrainian Legion - allies of Nazis, rivals of Bendera.. BBC World Service - Russian Service, 02/09/2009.

- ↑ "Prezentacja książki "Deportacje obywateli polskich z Zachodniej Ukrainy i Zachodniej Białorusi w 1940 roku"" [Book launch "The deportation of Polish citizens from Western Ukraine and Western Belarus in 1940"]. ipn.gov.pl. 30 March 2004. Archived from the original on 2011-05-15.

_..jpg)