Cherokee military history

The Cherokee people of the southeastern United States, and later Oklahoma and surrounding areas, have a long military history. Since European contact, Cherokee military activity has been documented in European records. Cherokee tribes and bands had a number of conflicts during the 18th century with European colonizing forces, primarily the English. The Eastern Band and Cherokees from the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) fought in the American Civil War, with bands allying with the Union or the Confederacy. Because many Cherokees allied with the Confederacy, the United States government required a new treaty with the nation after the war. Cherokees have also served in the United States military during the 20th and 21st centuries.

Traditional military leadership

Before the 18th century, Cherokee political leadership (much like that of the neighboring Muscogee and Natchez tribes) was dual or shared by two chiefs: "white" (peace) and "red" (war) leaders. During a conflict, the red chief would organize young men into war parties. He was assisted by a deputy chief, a speaker and messengers. Decisions were made by a war council composed of delegates from the seven Cherokee clans. War women, including the "beloved woman" (Ghigau), could participate in the council or accompany war parties. Scouts and medicine men would round out the war party.[1]

War of the Cherokee and Chickasaw with the Shawnee (1710)

Around 1710 the Cherokee and the Chickasaw forced their enemy, the Shawnee, north of the Ohio River.[2] During the 1660s, the Cherokee had allowed a refugee group of Shawnee to settle in the Cumberland Basin when they fled the Iroquois during the Beaver Wars. The Shawnee were also a buffer against the Cherokee, traditional Chickasaw enemies.

The Cherokee allowed another group of Shawnee to pass through their territory to settle on the Savannah River, where they would be a buffer against the Catawba. More Shawnee (allied with the French) entered the region, attracting the attention of the Iroquois, and the British-allied Cherokee and Chickasaw decided to act in concert to expel the Shawnee from their territory. The conflict lasted from 1710 to 1715, and sporadic warfare continued for more than 50 years. In 1768, the Shawnee and Cherokee forged a peace treaty.

Tuscarora War

Except for limited trading contact, the Cherokee were relatively unaffected by the presence of European colonists in North America until the Tuscarora War. In 1711, the Tuscarora began attacking colonists in North Carolina after diplomatic attempts to resolve grievances failed. The governor of North Carolina asked South Carolina for military aid. Before the war ended several years later, South Carolina sent two armies against the Tuscarora. Both were composed primarily of Indians, especially Yamasee troops.

The first army, commanded by John Barnwell, campaigned in North Carolina in 1712. By the end of the year a fragile peace existed, and the army dispersed; no Cherokee were involved in the first army. Hostilities between the Tuscarora and North Carolina broke out soon afterwards.

In late 1712 to early 1713, a second army from South Carolina fought the Tuscarora. This army consisted of about 100 British and over 700 native soldiers. Like the first army, the second depended heavily on the Yamasee and Catawba; this time, however, hundreds of Cherokee also joined the army. The campaign ended after a Tuscarora defeat at Hancock's Fort, and over 1,000 Tuscarora and allied Indians were killed or captured. The prisoners were primarily sold into the Indian slave trade. Although the second army from South Carolina disbanded soon after the battle, the Tuscarora War continued for several years. Some previously-neutral Tuscarora became hostile, and the Iroquois entered the dispute. Many Tuscarora ultimately moved north to live among the Iroquois.

The Tuscarora War altered the geopolitical context of colonial America in several ways, increasing Iroquois interest in the south. For the many southeastern natives involved, it was the first time so many had collaborated on a military campaign and their first glimpse of how the English colonies differed. As a result, the war helped bind the region's Indians and enhanced their communication and trade networks. The Cherokee became more closely integrated with the region's Indians and Europeans. The Tuscarora War began an English-Cherokee relationship which, despite occasional breakdowns, remained strong for much of the 18th century.

Destruction of Chestowee

The Tuscarora War also marked the rise of Cherokee military power, demonstrated in the 1714 attack and destruction of the Yuchi town of Chestowee (in today's Bradley County, Tennessee). English traders Alexander Long and Eleazer Wiggan instigated the attack with deceptions and promises, although there was a preexisting conflict between the Cherokee and the Yuchi. The traders' plot was based in the Cherokee town of Euphase (Great Hiwassee), and primarily involved local Cherokees.

In May 1714, the Cherokee destroyed Chestowee. Surviving inhabitants who were not captured fled to the Creek or the Savannah River Yuchi. Long and Wiggan told the Cherokee, falsely, that the South Carolina government supported the attack. When he heard about the deception the South Carolina governor sent a messenger to tell the Cherokee not to continue the attack on the Yuchi, but the messenger arrived too late to save Chestowee. The Cherokee attack on the Yuchi ended with Chestowee, but it caught the attention of every tribe and European colony in the region. Around 1715, the Cherokee emerged as a major regional power.[3]

Yamasee War

In 1715, as the Tuscarora War was winding down, the Yamasee War broke out and a number of tribes launched attacks in South Carolina. The Cherokee participated in some attacks, but were divided over which course to take. After South Carolina's militia drove off the Yamasee and the Catawba, the Cherokee became pivotal; South Carolina and the Lower Creek tried to enlist Cherokee support. Some Cherokee favored an alliance with South Carolina and war on the Creek, and others favored the opposite.

The impasse was broken in January 1716, when a delegation of Creek leaders was murdered at the Cherokee town of Tugaloo, and the Cherokee launched attacks against the Creek. Peace treaties between South Carolina and the Creek were forged in 1717, undermining Cherokee commitment to war. Hostility and sporadic raids between the Cherokee and Creek continued for decades,[4] culminating with the Battle of Taliwa in 1755 at present-day Ball Ground, Georgia with the defeat of the Muscogee Creek. The Creek had already withdrawn most of their settlements from what is now North Georgia to create a buffer zone between themselves and the Cherokee.

In 1721 the Cherokee made their first cession of land to the British, selling the South Carolina colony a small strip of land between the Saluda, Santee and Edisto rivers. Moytoy of Tellico was chosen as "Emperor" by the elders of the principal Cherokee towns in 1730 at Nikwasi. Alexander Cumming had requested this to gain control of the Cherokee. Moytoy agreed to recognize King George II of Great Britain as protector of the Cherokee. Seven prominent Cherokee (including Attakullakulla) traveled with Cumming to England, and the Cherokee delegation spent four months in London. Their visit resulted in the 1730 Treaty of Whitehall, an alliance between the British and the Cherokee. The journey to London and the treaty were important to future British-Cherokee relations, but the title of Cherokee Emperor had little influence with the tribe. Although Moytoy's son Amouskosette tried to succeed him as "Emperor" in 1741, the power in the Overhill country had shifted to Tanasi and then to Chota.

The Cherokee "empire" was essentially ceremonial, with political authority remaining town-based for decades afterward, and Cumming's aspirations to play an important role in Cherokee affairs failed.[5] In 1735, the Cherokee were estimated to have 64 towns and villages and 6,000 fighting men. In 1738-39, smallpox was introduced to the country by sailors and slaves. An epidemic broke out among the Cherokee (who had no natural immunity), and nearly half their population died within a year; hundreds of others, disfigured by the disease, committed suicide.

War with the Muskogee-Creeks

According to Cherokee folklore, their conflict with the Muscogees was over disputed hunting grounds in North Georgia. The last phase of the war lasted from 1753 to 1755, and it began in 1715 after the Cherokee invited the Muskogean leaders (there was no Creek tribe then) to a diplomatic conference in the Cherokee town of Tugaloo at the headwaters of the Savannah River. At the behest of a Cherokee conjurer, the Cherokee hosts murdered the Creek leaders as they slept and precipitated a fifty-year war. English and French maps of the period show only a small area in northeastern Georgia occupied (or claimed) by the Cherokee, so the joint hunting grounds are a myth. However, after the Anglo-Cherokee War the British Crown created a 20-by-50-mile (32 by 80 km) joint hunting ground in the region.

Although the Cherokee remember the war as a victory as a result of the Battle of Taliwa on the Etowah River in northwestern Georgia, period archives belie their account. Northwestern Georgia was claimed by France and occupied by their Indian allies, the Apalachicola. The Muskogee-Creeks, allies of the Colony of Georgia and Great Britain, were never known to live (or claim) northwestern Georgia. The word "Taliwa" is Apalachicola (not Muskogee) for "town". It is unlikely that the Muskogee-Creeks, as allies of Great Britain, would have fought on behalf of Indians who were allied with France.

French military maps of the period show northwestern Georgia occupied by tribes allied with France until 1763; in 1757, a large contingent of Upper Creeks (also allied with France) relocated from what is now north-central Alabama to northwestern Georgia to reinforce the Apalachicola for six years. Although Taliwa may have been burned by an Overhills Cherokee army, it was not a Muskogee town and the battle was unrelated to the fifty-year war.

Evidence refuting the Cherokee version of the Cherokee-Muskogee War is in the Georgia Historical Society archives. Letters and reports from Georgia colonial officials and Indian traders describe attacks from 1750 to 1755 on Valley Cherokee towns in North Carolina and Lower Cherokee towns in northeastern Georgia, depopulating the Creek hunting grounds. A Georgia trader with the Creeks reported that the Coweta Creeks sent boys and women into battle to mock the Cherokee before defeating them. According to the trader, the Coweta Creeks maintained an area outside the town to burn Cherokee captives. The general reliability of these reports is confirmed by a 1755 map, prepared by John Mitchell, indicating that all the Valley and Georgia Cherokee towns were burned and abandoned that year.

Anglo-Cherokee War (1759–61)

After hearing reports of French fort-building plans in Cherokee territory (as they had Fort Charleville at the Great Salt Lick, now Nashville, Tennessee), the British built forts of their own: Fort Prince George near Keowee (in South Carolina), and Fort Loudoun, near Chota, in 1756. That year the Cherokee aided the British in the French and Indian War, but serious misunderstandings between the allies quickly arose. In 1760 the Cherokee besieged both British forts, forcing a relief army to retire at the Battle of Echoee and eventually capturing Fort Loudoun. The British retaliated by destroying 15 Cherokee communities in 1761, but a peace treaty was signed by the end of the year. King George III's Royal Proclamation of 1763 forbade British settlement west of the Appalachian crest, attempting to temporarily protect the Cherokee from encroachment, but enforcement was difficult.[6][7] The Cherokee and Chickasaw continued to war intermittently with the Shawnee along the Cumberland River for many years; the Shawnee allied with the Lenape, who remained at war with the Cherokee until 1768.

War with the Chickasaw and major land cessions in 1763

After their defeat by the Muskogee-Creek, the Valley Cherokee essentially ceased to exist. The Overhills Cherokee had lost several towns to the Upper Creeks during the first two years of the French and Indian War, but changed sides in 1757 (avoiding further losses). Still able to muster about 800 warriors, from 1758 to 1769 the Overhills Cherokee turned their attention west to the hunting grounds of the Chickasaw in what is now the portion of Alabama north of the Tennessee River. After eleven years of intermittent warfare, they were defeated at the Battle of Chickasaw Old Fields.

In 1763 the French and Indian War ended in victory for the British Empire, and the Cherokee were punished for switching sides in 1758 by the loss of their lands east of the 80-degree west-longitude line. The line, which crosses Murphy, North Carolina, is about 45 miles (72 km) west of the present Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians reservation. After losing all but the extreme western tip of North Carolina's current boundary, the surviving North Carolina Cherokee had nowhere to go. The British Crown allowed them to occupy the northwestern corner of what is now Georgia and the northeastern tip of present-day Alabama, areas formerly occupied by Indian allies of the French.

To reward the Muskogee-Creeks for their loyalty, the British Crown gave the remainder of Alabama to the Creeks and opened Florida to Creek migration. The Creeks who migrated to Florida became known as the Seminoles.

Watauga Association

Following the 1771 Battle of Alamance which ended the Regulator movement, many North Carolinians refused to take the new oath of allegiance to the British Crown and left the colony. One, James Robertson, led a group of 12 or 13 Regulator families westward from the area of present-day Raleigh. Believing that they were in the colony of Virginia, they settled on the banks of the Watauga River in present-day northeastern Tennessee. After a survey indicated their error, they were ordered them to leave. Cherokee leaders in the region interceded on their behalf, and they were allowed to remain if there was no further encroachment. In 1772, Robertson and the pioneers (who had settled along the Watauga, Doe, Holston and Nolichucky Rivers) met at Sycamore Shoals to establish a regional government known as the Watauga Association.[8]

Transylvania Purchase

In response to the first attempt by Daniel Boone and his party to establish a settlement inside their Kentucky hunting grounds, the Shawnee, Lenape (Delaware), Mingo and some Cherokees attacked a scouting and forage party which included Boone’s son. This sparked Dunmore's War (1773–1774), named after the governor of Virginia.

In 1775 a group of North Carolina speculators led by Richard Henderson negotiated the Treaty of Watauga at Sycamore Shoals with Overhill Cherokee leaders (chief of whom were Oconostota and Attakullakulla), in which the Cherokee gave their Kain-tuck-ee (Ganda'gi) lands to the Transylvania Land Company. The treaty disregarded claims to the region by other tribes, such as the Shawnee and Chickasaw. Area residents formed the Washington District, allying with the North Carolina colony for protection.

Dragging Canoe, chief of Great Island Town (Amoyeli Egwa) and son of Attakullakulla, refused to accept the deal: "You have bought a fair land, but there is a cloud hanging over it; you will find its settlement dark and bloody".[9] The governors of Virginia and North Carolina repudiated the Watauga treaty, and Henderson fled to avoid arrest.

Second Cherokee War

In 1776 the Shawnee chief Cornstalk led a delegation from the northern tribes to the southern tribes and met with Cherokee leaders at Chota, calling for united action against those whom they called the Long Knives. At the end of his speech he offered his war belt, and Dragging Canoe (Tsiyugunisini) and Abraham of Chilhowee (Tsulawiyi) accepted it. Dragging Canoe also accepted belts from the Odawa and the Iroquois, and Raven of Chota Savanukah accepted the Lenape war belt.

The Middle Towns were to attack South Carolina, the Lower Towns Georgia, and the Overhill Towns Virginia and North Carolina. The Overhill Cherokee was disastrous, particularly for those under Dragging Canoe against the Holston settlements because the settlers had been warned by Beloved Woman Nancy Ward. Abraham of Chilhowee could not take Fort Watauga, and Savanukah did no real military damage. After the failed raids, Dragging Canoe led his warriors to South Carolina to join the Lower Towns attack.

North Carolina sent 2,400 troops, including Rutherford's Light Horse cavalry, to scour the Middle Towns; South Carolina and Georgia sent 2,000 men to attack the Lower Towns. More than fifty towns were destroyed; houses and food were burned, orchards destroyed and livestock slaughtered. Hundreds of Cherokees were killed, and survivors were sold as slaves. Virginia sent a large force and North Carolina sent volunteers to the Overhill Towns. Dragging Canoe, who had returned with his warriors, ordered the Cherokee towns burned, women, children and the elderly moved south of the Hiwassee River and the Virginians ambushed at the French Broad River. Oconostota advocated peace at any price, supported by the rest of the older chiefs.

Dragging Canoe and his followers moved southwest as those from the Lower Towns poured into North Georgia. The Virginia force found Great Island, Citico (Sitiku), Toqua (Dakwa), Tuskeegee (Taskigi), and Great Tellico deserted, with only the older chiefs remaining. Christian, commander of the Virginia force, limited the reprisal in the Overhill Towns to the burning of deserted towns. In 1777 the Cherokee in the Hill, Valley, Lower, and Overhill Towns signed the Treaty of Dewitt’s Corner with Georgia and South Carolina and the Treaty of Fort Henry with Virginia and North Carolina, agreeing to stop warring and ceding the Lower Towns in return for protection from attack.

Cherokee–American wars

Dragging Canoe and his band migrated to the area near present-day Chattanooga, Tennessee, establishing eleven new towns (four of which were named for towns on the Little Tennessee River: Toqua, Citico, Tuskeegee and Chota). He made his headquarters in the town of Chickamauga, which lent its name to the surrounding area; frontiersmen and colonists called his band the Chickamauga or Chickamauga Cherokees, although they were never a separate tribe. Dragging Canoe began a guerrilla war which lasted nearly two decades and terrorized the western frontier, from the edge of the Muscogee nation north to the Ohio River and east into Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia.

Because of Chickamauga Cherokee activity, frontiersmen, colonies and states launched punitive raids against the Cherokee (usually the Overhill Towns). However, large forces invaded the Chickamauga area in 1777 and destroyed all eleven towns. After another invasion in 1782 Dragging Canoe and his people moved further west and southwest to what became known as the Five Lower Towns, west of the Cumberland Mountains and below the navigation hazards in the Tennessee River Gorge. Because of their new location and additional populations from the Lower Towns people, he and his people began to be known as the Lower Cherokee. Their headquarters was not invaded again until the final year of the wars.

Around this time that Dragging Canoe, now based in Running Water Town (Amogayunyi, present-day Whiteside, Tennessee), began to cooperate with the Upper Muscogee—usually as separate forces but sometimes combining for large operations. The Shawnee and other northern tribes were allies, and the Shawnee sent warriors to fight with his band. Chiksika and his younger brother, Tecumseh, were members of a Shawnee war party which remained for nearly two years. The Cherokee responded in kind, sending warriors north.

As Dragging Canoe and his fellows in the other southern tribes were forming a coalition to fight the Americans with the aid of the British, the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783. He went south to Pensacola, receiving support from the West Florida Spanish to continue his war and maintaining relations with the British governor at Detroit.

The 1788 murder of Old Tassel, headman of the Overhill Cherokee and chief of the Cherokee, and several other pacifist chiefs invited by the State of Franklin, outraged the Cherokee. More joined the Chickamauga Cherokee in their raids or carried out raids of their own. Franklin sent a large force to invade the Five Lower Towns, which was defeated at the foot of Lookout Mountain. Dragging Canoe raised an army of over 3,000 Cherokee and Muscogee which split into war bands, some of which were hundreds strong.

Four more years of frontier warfare ensued. Dragging Canoe returned to his hometown in 1792 after a long diplomatic trip in which the Lower Muscogee and Choctaw accepted his invitation to join the war; the Chickasaw declined. After a large dance at Lookout Mountain Town (Utsutigwayi or Stecoyee, present-day Trenton, Georgia) celebrating his diplomatic success and a recent raid by The Glass and his brother Turtle-at-Home on the Cumberland River into Kentucky, Dragging Canoe was found dead.

He was succeeded as leader of the Lower Cherokee by Old Tassel's nephew, John Watts, assisted by Bloody Fellow and Doublehead. Watts quickly renewed the alliance with Spain through West Florida and shifted his headquarters to Willstown (present-day Fort Payne, Alabama). The next year, he sent a delegation to Knoxville (capital of the Southwest Territory) to seek a peace. This delegation (which included his deputy, Doublehead) was attacked. Watts raised an army of over one thousand Cherokee, Muscogee and Shawnee. Although they were thwarted at Knoxville, they destroyed several smaller settlements along the way. Activities at one, Cavett's Station, set in motion rivalries which would dominate Cherokee affairs into the 19th century.

The following autumn (1794) General Robertson, military commander of the Mero District (as the Cumberland River settlements were called) in the Southwest Territory received word that the Lower Cherokee and Muscogee planned large-scale attacks on his region. He sent a large force of U.S. army regulars, Mero District militia and Kentucky volunteers south. The force destroyed Nickajack, one of the Five Lower Towns, and Running Water without warning. Most of the towns' population was at a stickball game several miles south, at Crow Town.

That incident and the defeat that summer of the army of their northern allies under the Shawnee Blue Jacket and the Miami Little Turtle convinced Watts and his fellow leaders that the end of the wars was inevitable. The Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse, ending the Cherokee–American wars, was signed on November 7, 1794.

After the wars

After the peace treaty, the Lower Cherokee leaders dominated national affairs. When the original Cherokee Nation was founded, the first three people to hold the office of Principal Chief—Little Turkey (1794–1801), Black Fox (1801–1811), and Pathkiller (1811–1827)—had served as warriors under Dragging Canoe (as had the first two speakers of the Cherokee National Council: Doublehead and Turtle-at-Home). Former Chickamauga warriors such as Bloody Fellow, the Glass and Dick Justice dominated the nation's political affairs for the next twenty years; although they were conservative, they embraced many aspects of acculturation.

The Lower Cherokee had their governmental seat at Willstown, in the Lower Towns (south of the Hiwassee River, along the Tennessee to the northern border of the Muscogee nation and west of the Conasauga and Ustanali in Georgia). The Upper Towns were north and east, between the Chattahoochee and Conasauga.

The seat of the Upper Towns was at Ustanali (near Calhoun, Georgia). It was also the titular seat of the nation, with former warriors James Vann and his protégés, The Ridge (formerly known as Pathkiller) and Charles R. Hicks—the Cherokee Triumvirate—their leaders (particularly of the younger, more-acculturated generation). The leaders of these towns were the most progressive, favoring acculturation, formal education and modern farming methods. Cherokee settlements in the highlands of western North Carolina, known as the Hill Towns with their seat at Quallatown, and the lowland Valley Towns (with their seat at Tuskquitee) were more traditional. So was the Upper Town of Etowah, inhabited mainly by full-bloods and the nation's largest town.

When the Cherokee Nation began to be pressured to migrate westward across the Mississippi, Lower Cherokee leaders were the first to leave; the remaining Lower Towns leaders, including Young Dragging Canoe and Sequoyah (George Guess), were the strongest advocates of migration. The domination of the nation's external affairs by former warriors lasted until an 1808 revolt by the young Upper Towns chiefs, which unseated Black Fox and the Glass until the reunification council at Willstown the following year abolished regional councils.[10][11]

American Civil War

Eastern band

Out of gratitude to William Holland Thomas, the western North Carolina Cherokee served in the American Civil War as part of what became known as the Thomas Legion of Cherokee Indians and Highlanders. Thomas' legion consisted of infantry, cavalry, and artillery. The legion mustered about 2,000 Cherokee and white men to fight for the Confederacy, primarily in Virginia; their battle record was outstanding.[12] Thomas' legion and the Western District of North Carolina, under Brigadier General John Echols (of which it was the only effective unit), surrendered after capturing Waynesville, North Carolina on May 9, 1865 when they learned about Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House. The decision to surrender was Echols', the senior commander; Thomas wanted to keep fighting. They agreed to cease hostilities if they could their arms for hunting. Brigadier General Stand Watie, commanding officer of the First Indian Brigade of the Army of the Trans-Mississippi and Principal Chief of the Confederate Cherokee, demobilized his forces under a cease-fire agreement with the Union commander at Fort Towson (in Choctaw Nation territory) on July 23, 1865.

Western bands

The Civil War was devastating for the Western Cherokee, who fought on both sides. After their forced removal from their southern homelands to the Indian Territory, the Cherokee were wary of the south; however, the Confederacy wooed them with promises of autonomy and land security. In 1861 the Confederacy had three regiments of Choctaw, Chickasaw, Cherokee, Creek and Seminole soldiers, who fought in the 1862 Battle of Pea Ridge in Arkansas.[13]

Because of Native alliances with the Confederacy, the 10th Regiment Kansas Volunteer Infantry (5,000 Union soldiers commanded by Colonel William Weer) swept through the Indian Territory in the summer of 1862. They fought the Confederacy at Locust Grove in the Cherokee Nation on July 2, 1862. On July 16 Captain Greeno's 6th Kansas Cavalry captured Tahlequah, the Cherokee Nation capital. On July 19 Colonel Jewell's 6th Kansas Cavalry captured Fort Gibson, a strategic port.[13]

Cherokees, Muscogee Creeks, and Seminoles joined Union regiments organized by William A. Phillips of Kansas. They fought in Missouri, Arkansas and at Honey Springs and Perryville in the Cherokee Nation.[13] Most Cherokee traditionalists supported the abolition of slavery, opposed the South and formed an association known as the Pin Indians, identifying themselves with a pair of crossed pins under their coat lapels.[14]

Principal Chief John Ross tried to keep the Cherokee Nation out of the war, issuing a proclamation of neutrality in 1861. Stand Watie, who supported the Confederacy, challenged Ross’ authority.[13] On May 21 of that year, the Cherokee held a council attended by over 4,000 men. Most who were present supported the South, and Ross conceded to maintain tribal unity.[14] The South seemed to be winning the war at the time, and Union politicians voiced anti-Indian sentiments. In October 1861, Ross signed a treaty with the Confederate States of America.[15] Union troops captured him during the summer of 1862; he was paroled, and spent the rest of the war in Washington and Philadelphia working to convince the Cherokee Nation government to remain loyal to the Union.[16]

In 1863 the Cherokee Nation abolished slavery, emancipating all Cherokee slaves.[17] Because the Nation allied with the Confederacy, the US government required a new treaty. The treaty stipulated that Cherokee freedmen must be accepted by the tribe as full members, as their counterparts became citizens of the United States throughout the South. On June 23, 1865, Brigadier General (and Cherokee leader) Stand Watie was the last Confederate general to surrender.[18]

20th century

Cherokees have served in both world wars. About 600 Cherokee and Choctaw served in the 142nd Infantry Regiment (United States) of the 36th Texas-Oklahoma National Guard Division during World War I.[19] Comanche and Navajo code talkers are well known, but as many as 40 Cherokee men also used their native language for sensitive communications during World War II.[20][21]

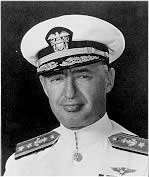

Admiral Joseph "Jocko" Clark, an Oklahoma Cherokee, was a highly-decorated admiral in the United States Navy for his command of aircraft carriers during World War II. Clark's rank was the highest achieved by a Native American in the US military.[22]

Second Lieutenant Billy Walkabout, an Oklahoma Cherokee from the Blue Clan, was the most-decorated Native American veteran of the Vietnam War. He served in the United States Army Company F, 58th Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division.[23]

21st century

The United Keetoowah Band Lighthorse Color Guard is composed of the band's military veterans. According to band chief George Wickliffe, "If you're Native American, you're going to fight harder. That's the kind of track record the Keetoowah Cherokee veterans have. You fought harder because this is your country".[24] Honorably-discharged Cherokee Nation veterans may join the Cherokee Nation Warriors Society, which provides color guards for civic events and powwows.[25] Veterans are honored at the Eastern Band's annual fall festival.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Sturtevant, 346

- ↑ Vicki Rozema, Footsteps of the Cherokees, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Gallay, Alan (2002). The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670–1717. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10193-7.

- ↑ Oatis, pp. 187–8

- ↑ Finger, John R. (2001). Tennessee Frontiers: Three Regions in Transition. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33985-5.

- ↑ Tortora, Daniel J. (2015). Carolina in Crisis: Cherokees, Colonists, and Slaves in the American Southeast, 1756–1763. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 1-469-62122-3.

- ↑ Rozema, pp. 17–23.

- ↑ Watauga Petition; Ensor Family Pages.

- ↑ Evans 1997, p. 179.

- ↑ McLoughlin, pp. 33–167.

- ↑ Wilkins, pp. 28–51.

- ↑ Will Thomas. "History and culture of the Cherokee (North Carolina Indians)" 2007-03-10

- 1 2 3 4 Britton, Wiley. "Battles and Leaders of the Civil War”, Civil War Home, retrieved 21 Sept 2009

- 1 2 Conley, p.174

- ↑ Conley, 175

- ↑ "We are all Americans", Native Americans in the Civil War. ‘’Fort Ward Museum and Historical Site.’’ (retrieved 21 Sept 2009)

- ↑ Gesick, John. Nineteenth-Century Practices, Twenty-First Century Decisions. Humanities and Social Sciences Online. March 2009 (retrieved 21 Sept 2009)

- ↑ Conley, 177

- ↑ Native Americans in the U.S. Military. Naval Historical Center.(retrieved 16 Sept 2009)

- ↑ Meadows, 71

- ↑ Ambrose, p. 144

- ↑ "Admiral Joseph Clark" Archived October 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine., Cherokee Heritage Center Education, (retrieved 16 Sept 2009)

- ↑ Billy Bob Walkabout, Second Lieutenant, United States Army. Arlington National Cemetery. (retrieved 16 Sept 2009)

- ↑ "United Keetoowah Band Honors Tribal Veterans" Archived April 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine., United Keetoowah Band of Cherokees, retrieved 18 September 2009

- ↑ Head Staff Profiles. Austin Powwow. (retrieved 18 September 2009)

References

- Ambrose, Stephen E. D-Day, June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II, Simon and Schuster, 1994. ISBN 978-0-671-67334-5.

- Conley, Robert J. The Cherokee Nation: A History, Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8263-3234-9

- Evans, E. Raymond. "Notable Persons in Cherokee History: Ostenaco", Journal of Cherokee Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 41–54. (Cherokee: Museum of the Cherokee Indian, 1976).

- Evans, E. Raymond. "Notable Persons in Cherokee History: Bob Benge". Journal of Cherokee Studies, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 98–106. (Cherokee: Museum of the Cherokee Indian, 1976).

- Evans, E. Raymond. "Notable Persons in Cherokee History: Dragging Canoe". Journal of Cherokee Studies, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 176–189. (Cherokee: Museum of the Cherokee Indian, 1977).

- Finger, John R. Cherokee Americans: The Eastern Band of Cherokees in the 20th Century. (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1991).

- McLoughlin, William G. Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0-691-00627-7.

- Meadows, William C. The Comanche code talkers of World War II, Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-292-75274-0.

- Rozema, Vicki. Footsteps of the Cherokees: A Guide to the Eastern Homelands of the Cherokee Nation, John F. Blair Publishing, 2007. ISBN 978-0-89587-346-0.

- Oatis, Steven H. A Colonial Complex: South Carolina's Frontiers in the Era of the Yamasee War, 1680–1730, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-8032-3575-5.

- Sturtevant, William C., general editor and Raymond D. Fogelson, volume editor. Handbook of North American Indians: Southeast. Volume 14. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2004. ISBN 0-16-072300-0.

- Tortora, Daniel J. Carolina in Crisis: Cherokees, Colonists, and Slaves in the American Southeast, 1756–1763. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015. ISBN 1-469-62122-3.

- Wilkins, Thurman. Cherokee Tragedy: The Ridge Family and the Decimation of a People, New York: Macmillan Company, 1970. ISBN 978-0-8061-2188-8.

- United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918," index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/KZ6N-98B : accessed 06 Jan 2014), Lige Meadows, 1917-1918; citing Memphis City no 4, Tennessee, United States, NARA microfilm publication M1509, (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d); FHL microfilm 1877500.