Charter of Ban Kulin

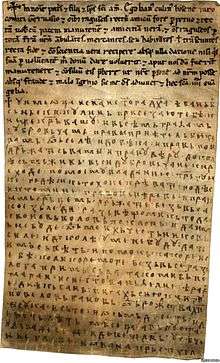

The Charter of Ban Kulin (Serbo-Croatian: Povelja Kulina bana/Повеља Кулина бана) was a trade agreement between the Banate of Bosnia and the Republic of Ragusa that effectively regulated Ragusan trade rights in Bosnia, written on 29 August 1189. It is one of the oldest written state documents in the Balkans.

According to the charter, Bosnian Ban Kulin promises to knez Krvaše and all the people of Dubrovnik full freedom of movement and trading across his country. The charter is written in two languages: Latin and an old form of Shtokavian dialect (Serbo-Croatian), with the Bosnian part being a loose translation of the Latin original.[2] The scribe was named as Radoje, and the script is Bosnian Cyrillic (Bosančica).[3]

The charter is of great significance in Bosnian national pride and historical heritage.[4]

Language

The Charter is the first diplomatic document written in the old Bosnian language and represents the oldest work written in the Bosnian Cyrillic script (Bosančica).[3] As such, it is of particular interest to both linguists and historians.

| Original Latin text | Original Slavic text |

|---|---|

| ☩ In noĩe pat̃s ⁊ filii ⁊ sp̃s sc̃i am̃. Ego banꝰ culinꝰ bosene juro comiti Geruasio ⁊ oĩbꝰ raguseis rectũ amicũ fore p̱petuo ⁊ rec |

☩ ꙋимеѡцаисн꙯аист꙯огадх꙯а·ѣбаньбⷪ сьньски:кꙋлиньприсеꙁаютебѣ:к |

| Latin transliteration | Bosnian translation | English translation |

|---|---|---|

| U ime oca i s(i)na i s(ve)toga d(u)xa.

Ě banь bosьnьski Kulinь prisezaju tebě kneže Krьvašu i vьsěmь građamь Dubrovьčamь pravy priětelь byti vamь odь selě i dověka i pravь goi drьžati sь vamy i pravu věru dokolě sьmь živь. Vьsi Dubrovьčane kire xode po moemu vladaniju trьgujuke gьdě si kьto xoke krěvati godě si kto mine pravovь věrovь i pravimь srь(dь)cemь drьžati e bezь vьsakoe zьledi razvě što mi kьto da svoiovь volovь poklonь; i da imь ne bude odь moixь čestьnikovь sile i dokolě u mene budu dati imь sьvětь i pomokь kakore i sebě kolikore moge bezь vьsega zьloga primysьla. Tako mi B(ože) pomagai i sie s(ve)to evanьđelie. Ě Radoe diěkь banь pisaxь siju knigu povelovь banovь odь rožestva X(risto)v(a) tisuka i sьto osьmьdesetь i devetь lětь měseca avьgusta u dьvadeseti i deveti d(ь)nь usěčenie glave Iovana Kr(ь)stit(e)la. |

U ime oca i sina i svetog duha.

Ja, ban bosanski Kulin, obećavam tebi kneže Krvašu i svim građanima Dubrovčanima pravim vam prijateljem biti od sada i dov(ij)eka i pravicu držati sa vama i pravo pov(j)erenje, dokle sam živ. Svi Dubrovčani koji hode kuda ja vladam, trgujući, gd(j)e god se žele kretati, gd(j)e god koji hoće, s pravim pov(j)erenjem i pravim srcem, bez ikakve zlobe, a što mi ko da svojom voljom kao poklon. Neće im biti od mojih časnika sile, i dokle u mene budu, davat ću im pomoć kao i sebi, koliko se može, bez ikakve zle primisli. Neka mi Bog pomogne i svo Sveto (J)Evanđelje. Ja Radoje banov pisar pisah ovu knjigu banove povelje od rođenja Hristova tisuću i sto i osamdeset i devet l(j)eta, m(j)eseca avgusta i dvadeset i deveti dan, (na dan) odrubljenja glave Jovana Krstitelja. |

In the name of the father and the son and the holy spirit.

I, the Bosnian ban Kulin, promise to thee comes Krvaš and all the citizens of Dubrovnik to be a true friend from now to forever. And I shall keep justice with you and true trust, as long as I live. All Dubrovnikans can walk where I rule, trade, move wherever they want to, with real confidence and real heart, without malice, and can give me gifts out of their own free will. They will not be forced by my officers, and as long as they stay in my lands, I will help them as I would myself, as I can, without any evil thoughts. God help me, and all of the Holy Gospel. I Radoje ban's scribe, wrote this book of ban's Charter, in the years since the birth of Christ a thousand and one hundred and eighty-nine, in the month of August in the twenty-ninth day (on the day of) decapitation of John the Baptist. |

Apart from the trinitarian invocation (U ime oca i sina i svetago duha), which characterizes all charters of the period, the language of the charter is completely free of Church Slavonic influence. The language of the charter reflects several important phonological changes that have occurred in Bosnian until the 12th century:[5]

- loss of Common Slavic nasal vowels /ę/ > /e/ and /ǫ/ > /u/

- loss of weak jers (occurred during the 10th century; ceased to be spoken in the 11th century). Scribal tradition preserved them word-finally but they were not actually uttered.

- The vowel yeri /y/ never occurs word-initially, and turns to /u/ after /k, g, x/. In the 12th century it has a very limited usage, and starts being replaced with the vowel /i/, a change also attested in Humac tablet.

- change of word-initial cluster vь- to /u/

History

The first to bring the charter to the public eye was Serbian émigrée Jeremija Gagić (1783–1859), the former Russian consul in Dubrovnik, who claimed to have saved the document in 1817. It was later known that the document was held in the Dubrovnik Archive until at least 1832, when it was copied by Đorđe Nikolajević and published in Monumenta Serbica. Nikolajević was entrusted with copying Cyrillic manuscripts from the Dubrovnik Archive in 1832 for scholarly publication, at which time he stole the Charter of Ban Kulin, along with other manuscripts such as the 1249 Charter of Ban Matej Ninoslav, the 1254 Charter of King Uroš I and Župan Radoslav, the 1265 letters of King Uroš I and the 1385 letters of King Tvrtko I. Jeremija Gagić obtained the Charter that Nikolajević stole, and sold or donated it to the Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg, where it is held today.[6] Dubrovnik Archive preserves another two copies of the Charter.

Analysis

Saint Petersburg copy is in the literature usually called "original" (or copy A), and copies stored in the Dubrovnik Archive as "younger copy" (or copy B) and "older copy" (or copy C). At first it was thought that the Saint Petersburg copy, which was the first one to be published and studied, was the original and others were much younger copies,[7] but that was called into question by later analyses. According to a study by Josip Vrana, evidence that the copy A represents the original remains inconclusive at best, and according to a comparative analysis the copy A represents only a conceptual draft of the Charter according to which the real original was written. Copies B and C are independent copies of the real original, which was different from the copy A.[8]

Palaeographic analysis indicates that all three copies of the charter were written in approximately the same period at the turn of the 12th century, and that their scribes originate from the same milieu, representing the same scribal tradition. Their handwriting on one hand relates to the contemporary Cyrillic monuments, and on the other hand it reflects an influence of the Western, Latin culture. Such cultural and literary opportunities have existed in the Travunia–Zeta area which encompassed the Dubrovnik region at the period.[9] Copy A probably, and copies B and C with certainty, originate from the scribe who lived and was educated in Dubrovnik and its surroundings.[10]

Linguistic analysis however does not point to any specific characteristics of the Dubrovnikan speech, but it does show that the language of the charter has common traits with Ragusan documents from the first half of the 13th century, or those in which Ragusan scribal offices participated.[11] Given that Ragusan delegates participated in the drafting of their copy, everything points that a scribe from Dubrovnik area must have participated in the formulation of the text of the copy A.[11] However, that the final text was written at the court of Ban Kulin is proved by how the date was written: using odь rožьstva xristova, and not the typical first-half-of-the-13th-century Dubrovnikan lěto uplьšteniě.[9]

Notes

- ↑ Liotta, P.H. (2001). Dismembering the State: The Death of Yugoslavia and Why It Matters. Lexington Books. p. 27. ISBN 0-7391-0212-5.

- ↑ Amira Turbić-Hadžagić, Bosanski književni jezik (prvi razvojni period od 9. do 15. stoljeća), – u Bosanski jezik, časopis za kulturu bosankoga književnog jezika br. 4, Tuzla, 2005.

- 1 2 Suarez, S.J. & Woudhuysen 2013, pp. 506-07.

- ↑ Mahmutćehajić, Rusmir (2003). Sarajevo essays: politics, ideology, and tradition. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. p. 252. ISBN 9780791456378.

- ↑ Dženeta Jukan (2009), Jezik Povelje Kulina bana, Diplomski rad, p. 13

- ↑ Vrana (1966:5–6)

- ↑ For example, Milan Rešetar dated the copies B and C into the latter half of the 13th century.

- ↑ Vrana (1966:46, 56)

- 1 2 Vrana (1966:54)

- ↑ Vrana (1966:46)

- 1 2 Vrana (1966:53)

References

- Vrana, Josip (1966), "Da li je sačuvan original isprave Kulina bana, Paleografijsko-jezična studija o primjercima isprave iz g. 1189." [Has the original of the Charter of Ban Kulin been preserved? A Paleographic-linguistic study of the copies of the monument from the year 1189.], Radovi Staroslavenskog instituta (in Croatian), Old Church Slavonic Institute, 2: 5–57

- Suarez, S.J., Michael F.; Woudhuysen, H.R. (2013). "The History of the Book in the Balkans". The Book: A Global History. Oxford University Press. pp. 506–07. ISBN 978-0-19-967941-6.