Charles W. Clark

| Charles W. Clark | |

|---|---|

Charles W. Clark in 1900 | |

| Born |

Charles William Clark 15 October 1865 Van Wert, Ohio |

| Died |

4 August 1925 (aged 59) Chicago |

| Citizenship | American |

| Occupation | Baritone singer |

| Years active | 1885–1925 |

Charles William Clark (15 October 1865 – 4 August 1925) was an American baritone singer and vocalist teacher. He is generally regarded as the first American baritone singer to be famous in Europe, and as one of the greatest baritone singers of all time. He sang to great acclaim at the major opera houses of Europe and America, appearing in a wide variety of roles from the Italian, French and German repertoires that ranged from the lyric to the dramatic.

Early life and music studies

Clark was born in Van Wert, Ohio on 15 October 1865. He was the fourth of eight children and the second of six to survive infancy. His father, William Asbury Clark, was a miller and a prominent citizen of Van Wert. Her mother was Virginia Adelia (Mahan) Clark.[1] Attended Van Wert High School and later the Methodist College in Fort Wayne, Indiana (today Taylor University).[2]

While studying at school, Clark worked in his father's mill in Van Wert as one of the boys who turned the grain into meal and into flour. He practiced singing as pleasure in his free time and during services at the First Methodist Church of Van Wert.

An 1884 accident led Clark to seriously consider a singing career. One day while working at the mill, a chip of stone flew off of one of the wheels and lodged in his eye. From the irritation that ensued, it was thought for a time that he would lose his sight. This made it impossible for Clark to continue working at the mill for a while.[3]

In 1885 began his vocalist studies at the age of 20 with Frederic W. Root in Chicago. This relationship lasted for ten years.[4] He gave his first public singing performances while studying with Root. He was immediately successful. Clark later described one of his early performances, saying:

I was to sing at a concert given in one of the suburbs of Chicago at a mission, of which a young minister was the head. He was trying to do something to advance things a bit, and we arranged on a sharing basis: he to pay the expenses of the concert. I loaned him my cut for the advertising matter, and after the concert I lost track of him, but I knew where the printing had been done, and when I went there to get the cut I found they were holding it to pay for the printing bill which the minister had failed to settle; so I told them that if the cut was of any use to then they might have It, and they saw that it had nothing whatever to do with me and turned the cut over to me. My share of the receipts of this concert was $1.50, 12 admissions at 25 cents having been said.[3]

In November 7, 1888 Clark married Jessie Amanda Baker. Together they had five children: Helen, Charles R., Ronald B., Virginia and Louise; only the last three survived infancy.[5]

In 1894, he was engaged to sing in a performance of Haydn's Creation, where he was acclaimed by the public. This convinced him to continue his studies in Europe. The following were among the reviews of the performance:

Mr. Clark, the young baritone, sang his way into the hearts of his hearers at the very first number of the oratorio, and increased the liking by each number sang by him. ... Mr. Clark, the baritone, has such a glorious voice and such a manly presence and his enunciation is so clear and distinct, that one always felt a sense of longing unsatisfied when he was not singing.[3]

In 1895, after having sung in various American cities, he moved to London to study in the Royal Academy of Music under the direction of Alberto Randegger and George Henschel. In the course of the following year the latter engaged him as soloist with the London Henschel Orchestra.[6]

In 1896 while a student in London, he was also busy singing at functions. At the beginning of 1897 he returned for the first time to America. After his arrival, he received a letter asking him to go back to England a month earlier to sing the final scene from Die Walküre at a Wagner concert given on Wagner's birthday. In concert the previous fall he had sung the last scene from the opera; this was the opportunity to win artistic England. Clark made the success of his life. He was acclaimed the greatest artist who had ever sung the "Passion" music in England, notwithstanding the fact that many of the world's famous artists had given it before.[3]

Later on, in 1899 Clark went to Munich to study German Lied with Eugen Gura.[7]

Singing career

He made his first public appearance in London with the London Philharmonic Society in 1897. He sang "Wotan's Farewell", which he later sang at his first public appearance in Chicago in the same year with the Theodore Thomas Orchestra.[4]

On his return to America in 1897 he filled concert engagements in oratorio in most of the eastern cities, and under the direction of George Henschel, who was then touring the eastern states with his London Orchestra. Clark sang Henschel's Stabat Mater in Boston at the last concert at which Mrs. Henschel sang in America. At the same time he was also the bass soloist of the Handel and Haydn Society of that city.[6]

In 1898 he was first heard in New York in a performance of Messiah by the people's Choral Union at the Metropolitan Opera House.[8] Later that same year, Clark sang at the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition in Omaha, Nebraska, accompanying the Theodore Thomas Orchestra in several performances.[9] He also made his debut with the Thomas Orchestra that same year at the Auditorium in Chicago with immense success. At the close of his engagement in Chicago, Theodore Thomas advised Clark to return to Europe and locate for a time in Paris.[6]

In 1902 he took up his residence in Paris for the next twelve years [7] and was represented in Europe by concert agent L. G. Sharpe, who also represented Polish pianist Ignacy Paderewski.[10]

In 1903, Clark gave four concerts at the Paris National Conservatoire of Music, an honor that had not been given to an American in seventy years of those concerts. He sang at the Conservatory concerts each succeeding season in Paris appearing also with the Philharmonic Society and the Cologne Orchestra.[7]

Tours of Europe and America brought him great acclaim. He made six tours in America, toured Germany twice, and toured England, Ireland, Scotland, Italy and Portugal. He sang at Birmingham Festival, Liverpool Philharmonic concerts, with Halle Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra and at Broadwood concerts. He performed at Boosey´s London Ballad Concerts and the most important philharmonics and orchestras of his time. He gave more than 50 recitals only in London.[2]

In 1911 Clark interpreted for the first time the work Trois ballades de François Villon, composed by Claude Debussy in 1910, under the direction of the same composer at Concerts Séchiari. The same year, Clark presented this work for the first time in United States in New York, with the New York Symphony.[11]

Clark usually sang accompanied by the most famous and virtuous musicians of his time, like Claude Debussy, Pablo Casals, Ignacy Paderewski and Georg Schumann among others.[12]

Voice and temperament

Critics credited Clark with one of the finest baritone voices possessed by an American singer. He was praised for his fine, manly voice, his phrasing and his clear enunciation.

A note in the Spartanburg Herald appeared on April 5, 1914 which said:

Clark has been called "an embodied temperament". But the "storm and stress" period of youth is, in him, now refined and mellowed by study, constant singing in the world's great centres of art, and the experiences of life intensely and usefully lived. In his interpretations of the great masterpieces of music one finds, instead of a portrayal, a living picture. The composers' deeper meanings are penetrated and brought forth; every shade of every mood is intensified and presented vividly to the listener. The scholar and thinker are behind all that is sung; and a big voice, glorious in quality and of apparently limitless volume and beauty, is the vehicle of expression for all this fruit of genius and profound labor.[3]

A note in the Magazine The Musical Leader published on June 4, 1914 expressed the following:

Clark's position among the world's leading vocalist is due to a combination of the qualities that command success in special styles of singing, united to versatility. His recitals are framed with an eclectic taste and include examples from the Old Italian masters of the eighteenth century to modern French, German, Russian and English composers. He has been hailed in Paris as the great interpreter of Debussy, Faure and living French song writers, and in German as an artist of commanding power in the classical and modern German 'lieder.' He is also recognized as an oratorio singer of genius, and among his most striking and vivid impersonations may be mentioned Judas, in Elgar's Apostles, and the Prophet, in Elijah.[12]

Clark excelled as a Wagnerian singer. His temperament, his dramatic fervor, and his sincerity fitted him for it. His voice had the power and range for the typical Wagnerian singer, but it had none of the hardness which was too often associated with the performance of Wagner by singers of those years and nowadays.

In 1903, after having heard Clark sing in German and French, the King of England Edward VII turned to Consuelo, Duchess of Manchester and demanded, "Is Mr. Clark a Frenchman or German?" The duchess replied, with much pride, "He is an American, the same as I am." "Well," exclaimed his majesty, "I never had such a lump in my throat as when he sang 'Ich grolle nicht'".[3]

Clark had an almost stubborn devotion toward his ideal as an "interpreter of song". He repeatedly refused all offers from the realm of grand opera in spite of the insistence of his friends and fans.[13]

Other facts

Clark was head of the vocal department of the Bush Conservatory in Chicago, where he influenced and guided a number of students.[2]

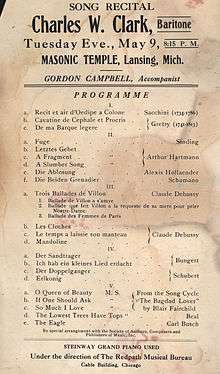

His performances and presentations were under the artistic direction of the Redpath Bureau, the oldest established concert bureau in USA. The bureau also directed the concerts in America of famous artists like Ignacy Paderewski, Madame Schumann-Heink and Pascuale Amato.

Clark's brother, physician and surgeon John Frederick Clark, was his personal representative in Chicago and was also a baritone and vocalist teacher. Together they formed the Clark Studios in Chicago, where they gave singing lessons and character recitals.[14]

His oldest sister Princess Clark was a soprano soloist. She was featured frequently at state conventions and served as a soloist at the Pittsburgh Centennial Convention of 1909.[15]

He was one of the first settlers at the artist colony in Grossmont on El Granito San Diego,[16] with other famous artists like poet John Vance Cheney, music critic Havrah Hubbard and opera singer Schumann-Heink. Madame Schumann-Heink had a picture of Clark hung in her home. She felt he had contributed an enormous amount to American music. His picture hung next to one of John D. Spreckels, the sugar magnate, one of her favorite people.[17]

During his life Clark was awarded with seven gold medals from the French government (Médaille de la Reconnaissance française) in recognition of his contribution to the French music and also to the French people during the First World War. It is said that war impressed him most through the destitute children of French musicians-soldiers, so he decided to "adopt" one hundred of them.[18]

Death

In August 4, 1925 while sitting in the Parkway Theatre in Chicago, Clark died of heart disease at the age of 59. His wife died later that day.[19] Both are buried at Woodland Union Cemetery in Van Wert, Ohio.

Recordings

There are five recordings by Clark that are registered in the Columbia A1400–A5999 (1913–1917) numerical listing.[20]

The first recording was produced in September 15, 1913 under the label A-5519. On one side of the recording is the tune "It is Enough" from Felix Mendelssohn's Elijah. On the other side is the tune "O Devine Redeemer" composed by Charles Gounod.

His second recording was produced under the label A-1470 on October 10, 1913. On one side is an "Irish Folk Song" composed by Arthur Foote. On the other side is the tune "Thy Beaming Eyes" of Edward MacDowell.

In his third recording produced under the label A-5610, the tune "O Star of Eve" from Richard Wagner's Tannhäuser (recorded on September 9, 1913) appears on one side. On the other side appears the tune "Fleeting Vision" composed by Jules Massenet and recorded on August 15, 1914.

The fourth recording was produced under the label A-1818 on March 15, 1915. On one side is the tune "I'm A Pilgrim (in A Strange Land)" composed by George Marston. On the other side is the tune "That Sweet Story of Old" composed by John A. West.

The last recording that appears on the Columbia Records Discography is unlabeled and was recorded on January 6, 1916. On one side appears the tune "Dream Faces" composed by William Marshall Hutchinson. On the other side appears the tune "Uncle Rome" composed by Sidney Homer and Howard Weedon.

Repertoire

|

"I'm A Pilgrim (in A Strange Land)"

A 1915 recording by Clark of "I'm A Pilgrim (in A Strange Land)" composed by George Marston "That Sweet Story of Old"

"That Sweet Story of Old" from John A. West sung in 1915 by Clark |

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

Clark's operatic repertoire consisted primarily of French, German and Italian works along with a few tunes in English. Below are the list of tunes that Clark usually sang in his programs, in alphabetical order by author.

- Die Ablösung (Alexis Hollaender)

- Letztes Gebet (Arthur Hartmann)

- A Fragment (Arthur Hartmann)

- A Slumber Song (Arthur Hartmann)

- The Lowest Trees Have Tops (Beal)

- Der Sandträger (Bungert)

- Ich hab ein kleines Lied erdacht (Bungert)

- The Eagle (Busch)

- Trois Ballades de Villon (Claude Debussy)

- Les Cloches (Claude Debussy)

- Le Temps a laissé son manteau (Claude Debussy)

- Mandoline (Claude Debussy)

- Monotone (Cornelius)

- Judas (Elgar)

- O Queen of Beauty (Fairchild)

- If One Should Ask (Fairchild)

- So Much I Love (Fairchild)

- Love Dirge (Farrari)

- Joy (Farrari)

- Irish Folk Song (Foote)

- O Divine Redeemer (Gounod)

- Cavatine de Cephale et Procris (Gretry)

- De ma Barque legere (Gretry)

- Ballad of the Bonny Fiddler (Hammond)

- Recompense (Hammond)

- Where'er you Walk (Händel)

- Morning Hymn (Henschel)

- Uncle Rome (Hommer and Weedon)

- Stuttering Lovers (Hughes)

- Cato's Advice (Huhn)

- Thy Beaming Eyes (MacDowell)

- Dream Faces (Marshall)

- I'm a Pilgrim (Marston)

- Vision Fugitive (Massenet)

- Fleeting Vision (Massenet)

- Prophet (Mendelsohnn)

- It's Enough (Mendelsohnn)

- Sylvia, now your scorn give over (Purcell)

- I'll sail upon the dog star (Purcell)

- Ectasy (Rummel)

- Recit et air d'Odipe a Colone (Sacchini)

- Aufenthalt (Schubert)

- Das Fischermädchen (Schubert)

- Der Doppelgänger (Schubert)

- Erlkönig (Shubert)

- Die beiden Grenadiere (Schumann)

- Ich grolle nicht (Schumann)

- Fuge (Sinding)

- Wotan's Farewell (Wagner)

- O Star of Eve (Wagner)

- That Sweet Story of Old (West)

References

- ↑ Thaddeus Stephens Gilliland. History of Van Wert County, Ohio and Representative Citizens, Richmond & Arnold, 1906, p. 361.

- 1 2 3 John William Leonard, The book of Chicagoans: A biographical dictionary of leading living men and women of the city of Chicago, A.N. Marquis, 1917, p. 134.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Clark, The Miller, Great Baritone", The Spartanburg Herald, South Carolina, 5 April 1914, p. 2.

- 1 2 Song Recital, , The Daily Princetonian, New Jersey, 14 March 1906, p. 1.

- ↑ Elwood Thomas Baker, A genealogy of Eber and Lydia Smith Baker of Marion, Ohio, and their descendants, Lydia A. Copeland, 1909, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 American Students' Census, Paris, 1903, Achievements of prominent Americans abroad; biographies of the greatest professors of singing in Paris, McProud, Laura (pseud. of Louella B. Mendenhall); Souvenir of the Louisiana Purchase, 1903, p. 127.

- 1 2 3 Clark, Charles W. Biography. Musical Biographies, Grande Musica website.

- ↑ "Concert In Aid of Charity", The New York Times, New York, 16 January 1898.

- ↑ Grace Carey. Music at the Fair! The Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition. An Interactive Website, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2006, pp. 9, 10, 23 and 24.

- ↑ Christopher Fiefield. Ibbs and Tillett: The Rise and Fall of a Musical Empire, Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2005, ISBN 1-84014-290-1, p. 85.

- ↑ Trois ballades de François Villon. Voix, orchestre, sur le site de la Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- 1 2 "Great Britain to Hear American Baritone", The Musical Leader, Volume 27, No. 23, Chicago–New York, 4 June 1914, p. 859.

- ↑ The Musical Monitor and World. A Magazine, January 1914, p. 136.

- ↑ "C. W. Clark To Tour England This Fall", The Musical Leader, Volume 27, No. 23, Chicago–New York, 4 June 1914, p. 874.

- ↑ Debra B. Hull. "Christian Church Women, Shapers of a Movement", Chalice Press, 1 January 1994, ISBN 978-0827204638, p. 25.

- ↑ Richard Crawford. "Entertainer Founded Grossmont", San Diego Union Tribune, 3 April 2010. p. EZ1.

- ↑ Kathleen Crawford. "Great God's Garden: The Grossmont Art Colony", The Journal of San Diego History, Volume 31, Number 4, San Diego, Fall 1985.

- ↑ Four Concerts for Philharmonic Society To Be Given This Week; Three Soloists New York Herald Sunday, February 3, 1918, Third Section, page 4.

- ↑ "Baritone Clark Dies; Wife's Death Follows", The New York Times, New York, 4 August 1925.

- ↑ Tim Brooks, Brian Rust. The Columbia Master Book Discography, Volume II: Principal U.S. Matrix Series, 1910–1924, Greenwood, 1999, ISBN 0-3133-0822-5, p. 87, p. 122, p. 158.

Primary sources

- Brooks, Tim; Rust, Brian. The Columbia Master Book Discography, Volume II: Principal U.S. Matrix Series, 1910–1924, Greenwood, 1999, ISBN 0-3133-0822-5.

- Crawford, Kathleen. "Great God's Garden: The Grossmont Art Colony", The Journal of San Diego History, Volume 31, Number 4, San Diego, Fall 1985.

- Crawford, Richard. "Entertainer Founded Grossmont", San Diego Union Tribune, 3 April 2010. pEZ1.

- Baker, Elwood Thomas. A genealogy of Eber and Lydia Smith Baker of Marion, Ohio, and their descendants, Lydia A. Copeland, 1909.

- Fiefield, Christopher. Ibbs and Tillett: The Rise and Fall of a Musical Empire, Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2005, ISBN 1-84014-290-1.

- Gilliland, Thaddeus Stephens. History of Van Wert County, Ohio and Representative Citizens, Richmond & Arnold, 1906.

- Ingram, William H. Who's who in Paris Anglo-American Colony; a biographical dictionary of the leading members of the Anglo-American colony of Paris, 1905, Nabu Press 2012, ISBN 978-1286269954.

- Leonard, John William. The Book of Chicagoans: A Biographical Dictionary of Leading Living Men and Women of the City of Chicago, A.N. Marquis, 1917.

- "Song Recital", The Daily Princetonian, New Jersey, March 14, 1906.

- Saerchinger, César. International Who's Who in Music and Musical Gazetteer, Nabu Press 2012, ISBN 978-1293359693.

- The Musical Leader. Volume 27, No. 23, Chicago – New York, June 4, 1914.

- The Musical Monitor and World. Chicago, September 1913, January 1914 and April, 1914.

- Thompson, Oscar. The International Cyclopedia of Music and Musicians, Dodd, Mead; 10th ed edition (1975), ISBN 978-0396070054.

- "Concert In Aid of Charity", The New York Times, New York, January 16, 1898.

- "Mr. Clark's Recital", The New York Times, New York, November 23, 1900.

- "Baritone Clark Dies; Wife's Death Follows", The New York Times, New York, August 4, 1925.

- "Extraordinary Musical Attraction", The Pullman Herald, Washington, January 23, 1914.

- "Clark, The Miller, Great Baritone", The Spartanburg Herald, South Carolina, April 5, 1914.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles W. Clark. |

- Charles W. Clark Biography. Grande Musica

- Aid French War Charity.; Arthur Shattuck, Pianist, and Chas. W. Clark, Baritone, in Recital – The New York Times article, February 9, 1918

- Mr. Clark Recital at Mendelssohn Hall – The New York Times article, November 23, 1900

- Concert in Aid of Charity.; Seidl and His Orchestra to Play in a Benefit for the Workingmen's School Next Month – The New York Times article, January 16, 1898

- Charles W. Clark's Recital.; The Chicago Baritone Sings in Mendelssohn Hall – The New York Times article, March 14, 1906

- Symphony Society's Varied Programme; Bach, Mendelssohn, and Tschaikowsky Represented in Selections at Yesterday's Concert, The New York Times article, March 18, 1911