Charles Ray Hatcher

| Charles Ray Hatcher | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

July 16, 1929 Mound City, Missouri, United States |

| Died |

December 7, 1984 (aged 55) Missouri State Penitentiary in Jefferson City, Missouri |

| Cause of death | Suicide |

| Other names |

|

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment |

| Killings | |

| Victims | 16 |

Span of killings | 1969–1982 |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | Missouri, California, Illinois |

Date apprehended | July 30, 1982 |

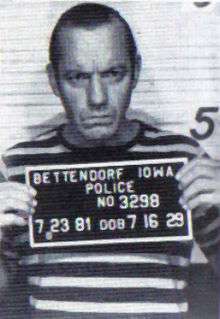

Charles Ray Hatcher (July 16, 1929 – December 7, 1984) was an American serial killer who confessed to having murdered 16 people between 1969 and 1982.

Childhood and youth

Charles Ray Hatcher was born in Mound City, Missouri, a small town 34 miles (55 km) north of St. Joseph. He was the youngest of Jesse and Lula Hatcher's four children. His father was an ex‑convict and an abusive alcoholic. Hatcher was bullied in school, and he would often inflict pain on his classmates.

In the spring of 1935, he and his older brothers were flying a kite with copper wire they had found in an old Model T Ford. His oldest brother, Arthur Allen, was about to hand the kite to him when it hit a high‑voltage power line and electrocuted him. Arthur was pronounced dead at the scene. Soon afterward, his father left home and divorced his mother. His mother remarried several times, and in 1945, Hatcher moved with his mother and her third husband to St. Joseph.[1]

Crimes

1947–1963

In 1947, Hatcher was convicted of auto theft in St. Joseph after stealing a logging truck from Iowa–Missouri Walnut Company, his employer of two weeks. He received a two‑year suspended sentence. In 1948, he was convicted of auto theft a second time for stealing a 1937 Buick in St. Joseph. Hatcher was sentenced to two years in the Missouri State Penitentiary. On June 8, 1949, Hatcher was released from prison after serving a little more than half of his time; however, he was back in prison in just a few months, after being convicted of forging a $10 check at a gas station in Maryville, Missouri. On March 18, 1951, Hatcher escaped from prison and attempted a burglary, but was caught and received an extra two years in prison.[1]

After serving his additional time, Hatcher was released from prison on July 14, 1954. He stole a 1951 Ford in Orrick and was subsequently sentenced to four years in prison. Before he was sentenced, Hatcher attempted to escape from the Ray County Jail in Richmond and received an additional two years. On March 18, 1959, Hatcher was released from prison after the sixth prison sentence of his life.[1]

On June 26, 1959, Hatcher attempted to abduct Steven Pellham, a 16‑year‑old in St. Joseph who delivered newspapers, threatening him with a butcher knife. Pellham reported the crime, and Hatcher was arrested when the police stopped him in a stolen vehicle.[1]

Hatcher was sentenced to five years in the Missouri State Penitentiary for the attempted abduction and auto theft under the Habitual Criminal Act. While Hatcher was waiting to be transported to prison, he unsuccessfully attempted to break out of the Buchanan County Jail. When Hatcher arrived at the Missouri State Penitentiary, he claimed to be the most notorious criminal in northwest Missouri since Jesse James.[1]

On July 2, 1961, inmate Jerry Tharrington was found raped and stabbed to death on the prison’s kitchen loading dock. Hatcher was the only one missing from the kitchen crew at the time of the murder. He was sent to solitary confinement for Tharrington’s murder, but there was not enough evidence to convict him in court. While in solitary confinement for the murder, Hatcher wrote a note claiming that he needed psychiatric treatment; however, the prison psychologist felt that it was simply a scheme to get out of solitary and possibly out of prison early. Treatment was refused, and Hatcher was returned to the general population. His sentence was reduced to three‑quarters the original time, and he was released on August 24, 1963.[1]

1969–1977

Hatcher confessed to abducting a 12‑year‑old named William Freeman in Antioch, California on August 27th, 1969. He claimed he had told the boy to come with him, took him to a creek, and strangled him.[1]

On August 29, 1969, six‑year‑old Gilbert Martinez was reported missing in San Francisco. According to the six‑year‑old girl with whom he was playing, Martinez walked away with a man who offered him ice cream. He was found by a man walking his dog as the boy was being beaten and sexually assaulted. Police arrived and arrested the assailant, who identified himself as Albert Ralph Price, although he carried identification with the name Hobert Prater. Martinez survived the assault, and Federal Bureau of Investigation records later identified the man as Charles R. Hatcher.[1]

Still going by the name Albert Price, Hatcher was charged with assault with attempt to commit sodomy and kidnapping. He was ordered to undergo competency evaluations to determine his competence to stand trial. A complete psychological evaluation was ordered when Hatcher was unresponsive during the preliminary evaluations. During this time, he claimed to hear voices, and faked delusions and suicide attempts to avoid prison.[1]:2–3

In December 1970, Hatcher was sent back and forth between the courts and hospital multiple times. One psychiatrist diagnosed him as having a passive–aggressive personality with paraphilia and pedophilia. It was reported that the hospital staff felt Hatcher was fabricating or exaggerating the symptoms of his mental disorders. He was examined by two psychiatrists in January 1971. He was declared insane by the first one, who recommended vigorous treatment in a secure hospital. The second psychiatrist declared him to be incompetent to stand trial and sent him back to the hospital.[1]

On May 24, 1971, Hatcher was sent to trial and pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity. He was sent to a different hospital for more evaluations, where it was determined that he was unfit to stand trial. On June 2, Hatcher escaped from the hospital. He was caught a week later in Colusa, California and arrested for suspected auto theft under the name Richard Lee Grady. Hatcher was returned to the California State Hospital for a mental evaluation. In April 1972, hospital staff determined that his treatment was unsuccessful and that he was a danger to other patients, after which he was sent to the prison state hospital in Vacaville.[1]

In August 1972, Hatcher was transferred to San Quentin State Prison to stand trial, three years after the crime. He was ordered to undergo two final examinations: one declared him competent to stand trial and the other determined him to be sane at the time of the crime.[1]

In December 1972, Hatcher was tried for, and convicted of the abduction and molestation of Martinez. In January 1972, he was committed to the California State Hospital as a "mentally disordered sexual offender".[1]

On March 28, 1973, security guards found Hatcher hiding in a cooler near the hospital's main courtyard with two sheets stuffed into his pants, after which he admitted to an escape attempt. He was sent back to court for sentencing after doctors determined he was still a threat to society. In April, Hatcher was sentenced to one year to life and sent to a medium‑security prison in Vacaville.[1]

In May 1973, a psychologist found Hatcher to be a "manipulative institutionalized sociopath".[1] In June 1973, he attempted suicide by slashing his wrists after it was recommended that he be transferred to a maximum security prison. A psychiatrist diagnosed him with paranoid schizophrenia, and he remained at Vacaville.[1]

In August 1975, guards reported good behavior at Hatcher's parole review. In June 1976, the California Parole Board found that Hatcher had improved dramatically through his time in prison and set a parole date of December 25, 1978. As a result of the passage of a bill giving inmates credit for time spent in jails and mental hospitals, Hatcher received a modified parole date in January 1977. He was released to a halfway house in San Francisco on May 20, 1977.[1]

1978–1982

On September 4, 1978, Hatcher was arrested under the name Richard Clark in Omaha, Nebraska for sexually assaulting a 16‑year‑old boy. He was sent to the Douglas County Mental Hospital and released in January 1979.[1]

On May 3, 1979, Hatcher was arrested for assault and attempted murder after he tried to stab seven‑year‑old Thomas Morton. He was sent to Norfolk Regional Center, a mental health facility, after the charges were dropped.[1]

In May 1980, Hatcher was released from the facility but was sent back two months later for another assault. He escaped in September.[1]

On October 9, 1980, Hatcher was arrested as Richard Clark in Lincoln, Nebraska for the attempted assault and sodomy of a 17‑year‑old boy. He was sent to another mental health facility and released after 21 days.[1]

On January 13, 1981, Hatcher was arrested as Richard Clark in Des Moines, Iowa after a knife fight. He spent time in several mental health facilities and was released to a Davenport Salvation Army shelter in April.[1]

Melvin Reynolds

On May 26, 1978, four‑year‑old Eric Christgen disappeared from downtown St. Joseph, Missouri. His body was later found along the Missouri River; he had been sexually abused and died of suffocation. The police questioned more than 100 possible suspects, including "every known pervert in town", to no avail.[2]:141 One of them was Melvin Reynolds, a 25‑year‑old man of limited intelligence who had been sexually abused himself as a child and who had homosexual experiences as an adolescent. Reynolds, although agitated by the investigation, cooperated through several interrogations over a period of months, including two polygraph examinations and one interrogation under hypnosis. In December 1978, he was questioned under amobarbital – believed at the time to be a truth serum – and made an ambiguous remark that intensified police suspicion. Two months later, in February 1979, the police brought the still cooperative Reynolds in for another round of interrogation: fourteen hours of questions, promises, and threats. Finally, Reynolds gave in and said, "I'll say so if you want me to".[2]:141 In the weeks that followed, Reynolds embellished this confession with details that were fed to him, deliberately or otherwise. That was enough to convince the prosecutor to charge Reynolds, and to convince a jury to convict him of second‑degree murder. He was sentenced to life imprisonment. Four years later, Reynolds was released when Charles Hatcher confessed to three murders to an FBI agent, including that of Eric Christgen.[2]

Death

On July 29, 1982, 11‑year‑old Michelle Steele was reported missing from St. Joseph. The day after, her uncle found her nude, ravaged body on a bank of the Missouri River; she had been beaten and strangled to death.[1] Hatcher was arrested the following day, as he tried to check in at the St. Joseph State Hospital. While awaiting trial, he confessed to fifteen other child‑murders dating from 1969. The first victim, 12‑year‑old William Freeman, had disappeared from Antioch, California, in August of that year, one day before Hatcher was charged with child molestation in nearby San Francisco. In another case, Hatcher penned a crude map that led searchers to the remains of James Churchill, buried on the grounds of the Rock Island Army Arsenal, near Davenport, Iowa. It was then that he also confessed to the murder of Eric Christgen. He was convicted of the Christgen homicide in October 1983, and drew a term of life imprisonment with no parole for at least 50 years. Facing his second Missouri conviction a year later for the murder of Michelle Steele, Hatcher requested a death sentence but the jury refused, recommending life on December 3, 1984. Four days later, Hatcher hanged himself in his cell, at the Missouri State Penitentiary in Jefferson City.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Keen, Amber; Lewis, George; Stone, Kara; Lucas, Andrew (2005). "Charles Ray Hatcher" (PDF). Radford University Department of Psychology. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Gross, Samuel R. (1998). "Lost Lives: Miscarriages of Justice in Capital Cases". Law and Contemporary Problems. Duke University School of Law. 61 (4): 125–152. doi:10.2307/1192432. ISSN 0023-9186. JSTOR 1192432. Archived from the original on March 12, 2002.