Charles-Henri Sanson

| Charles-Henri Sanson | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Charles-Henri Sanson | |

| Born |

15 February 1739 Paris, France |

| Died |

4 July 1806 (aged 67) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Royal Executioner of France, High Executioner of the First French Republic |

Charles-Henri Sanson, full title Chevalier Charles-Henri Sanson de Longval (15 February 1739 – 4 July 1806) was the Royal Executioner of France during the reign of King Louis XVI, and High Executioner of the First French Republic. He administered capital punishment in the city of Paris for over forty years, and by his own hand executed nearly 3,000 people, including the King himself.

Family history

Charles-Henri Sanson was the fourth in a six-generation family dynasty of executioners. His great-grandfather, a soldier in the French royal army named Charles Sanson (1658–1695) of Abbeville, was appointed as Executioner of Paris in 1684.[1] Upon his death in 1695, the Sanson patriarch passed the office to his son, also named Charles (1681- September 12, 1726). When this second Charles died, an official regency held the position until his young son, Charles John Baptiste Sanson (1719 - August 4, 1778), reached maturity. The third Sanson served all his life as High Executioner, and in his time fathered sixteen children, ten of whom survived to adulthood. The eldest of his sons, Charles-Henri - known as "The Great Sanson" - apprenticed with his father for twenty years, and was sworn into the office on December 26, 1778.[2]

Life

Charles-Henri Sanson was born in Paris to Charles-Jean-Baptiste Sanson and his first wife Madeleine Tronson. He was first raised in the convent school at Rouen until in 1753 a father of another student recognized Charles-Henri's father as the executioner and he had to leave the school, much to the regret of the principal, in order to not ruin the school's reputation. Charles-Henri was then privately educated. He had a strong aversion towards his family's business.

Executioner as a career

His father's paralysis and the assertiveness of his paternal grandmother, Anne-Marthe Sanson, led Charles-Henri to leave his study of medicine and to assume the job of executioner in order to guarantee the livelihood of his family. As executioner (bourreau) he came to be known as "Monsieur de Paris" - "Gentleman of Paris". On January 10, 1765, he married his second wife, Marie-Anne Jugier. They had two sons: Henri (1767–1830), who became his official successor, and Gabriel (1769–1792), who also worked in the family business.

In 1757 Sanson assisted his uncle Nicolas-Charles-Gabriel Sanson (1721–1795, executioner of Reims) with the extremely gruesome execution of the King's attempted assassin Robert-François Damiens. Through his well-executed intervention he shortened the quartering of the delinquent and thus the pain. His uncle quit his position as executioner after this event. In 1778 Charles-Henri officially received the blood-red coat, the sign of the master executioner, from his father Charles-Jean-Baptiste and held this position for 38 years, until his son Henri in 1795 succeeded him after he showed serious signs of illness. The majority of the executions were performed by Sanson and up to six assistants.

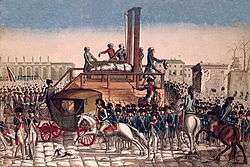

Charles-Henri Sanson performed 2,918 executions, including Louis XVI. Even though he was not a supporter of the monarchy, he was initially reluctant to execute the king but in the end performed the execution.“No Monsieur de Paris had ever had the honor of executing a king, and Sanson wanted precise instructions.”[3] There was a tremendous amount of pressure on Sanson. He had the power to execute Louis XVI. Regardless of how he personally felt it was his job to execute Louis XVI, and if he did not follow through with his orders it would bring shame to the family name, and he himself would more than likely have been executed. The stress and pressure of being the executioner and having to execute so many officials could have broken him. When studying the execution of Louis closely one can imagine that it would have been traumatic for anyone who had to lead it. “One of two accounts of Louis’ death suggest the blade did not sever his whole neck in one go, and had to be borne down on by the executioner to get a clean cut.”[4] If this is true the execution went from being quick and fast, to being more difficult and painful. “With his spine severed already, it is nevertheless unlikely that Louis could have uttered the ‘terrible cry’ that one account claims.”[5]

The Queen, Marie Antoinette, was executed by his son Henri, who succeeded his father in 1795 and Charles-Henri only attended. Later, using the guillotine, Sanson and his men executed successive waves of well-known revolutionaries, including Danton, Robespierre, Saint-Just, Hébert, and Desmoulins.

Supporter of the guillotine

After the Revolution, Sanson was instrumental in the adoption of the guillotine as the standard form of execution. After Joseph-Ignace Guillotin publicly proposed Antoine Louis' new execution machine, Sanson delivered a memorandum of unique weight and insight to the French Assembly.[6] Sanson, who owned and maintained all his own equipment, argued persuasively that multiple executions were too demanding for the old methods. The (relatively) lightweight tools of his trade were vulnerable under heavy usage, and the repair and replacement costs were prohibitive (an unfair burden on the executioner, he noted). Even worse, the physical exertion was too taxing and likely to result in accidents, and the victims themselves were likely to resort to acts of desperation during the lengthy, unpredictable procedures.[7]

When the guillotine's prototype was first tested on April 17, 1792, at Bicêtre Hospital in Paris, Sanson himself led the inspection. Swift and efficient decapitations of straw bales were followed by live sheep and finally human corpses: by the end, Sanson led the inspectors in pronouncing the new device a resounding success.[8] Within the week, the Assembly had approved its use and on April 25, 1792, Sanson inaugurated the era of the guillotine by executing the robber Nicolas Jacques Pelletier[9] at the Place de Grève.

Personal life

Sanson's hobbies included the dissection of those he executed and the production of medicines using herbs he grew in his garden. In his free time he liked to play the violin and cello, listened to Christoph Willibald Gluck, and often met with his longtime friend Tobias Schmidt, a well-regarded German maker of musical instruments who would later build Sanson's guillotine.

An anecdote reports that Charles-Henri Sanson after his retirement met Napoléon Bonaparte and was asked if he could still sleep well after having executed more than three thousand people. Sanson's laconic answer was, "If emperors, kings and dictators can sleep well, why shouldn't an executioner?"

Many would see Charles Henri Sanson as a sadistic man, but in reality he did not always enjoy his work. He would sometimes oppose what he did, and eventually the gore became too much for him. His position was seen as honorable, but internally he struggled. To further break the stereotype that all executioners were sadistic one can look at his diary and see that “he seems to have been a humane man, doing all that lay in his power to spare his victims unnecessary suffering.”[10] He felt as if the public did not fully understand executions. He felt that if people could really see and experience the fear from the victims, executions and the popularity for them would be less.[11]

Legacy

Sanson's eldest son Gabriel (1767–1792) had been his assistant and heir apparent from 1790, but the young man died after slipping off a scaffold as he displayed a severed head to the crowd.[12] With his death, the hereditary obligation fell to the youngest son, Henri (1769–1840), who was a soldier in the Revolution (sergeant, then captain of the national guard in Paris, later in the artillery and police of the Tribunals), and was married to Marie-Louise Damidot. Henri assumed the family office from Charles-Henri in August, 1795, and he remained the official Executioner of Paris for 47 years. Henri guillotined Marie Antoinette and the chief prosecutor Fouquier-Tinville (1795), among many others.

Charles Henri's grandson, Henry-Clément Sanson, was the sixth and last in the dynasty of executioners, serving until 1847.

In the late 1840s the Tussaud brothers Joseph and Francis, gathering relics for Madame Tussauds wax museum visited the aged Henry-Clément Sanson and secured parts of one of the original guillotines used during the Age of Terror. The executioner had "pawned his guillotine, and got into woeful trouble for alleged trafficking in municipal property".[13]

Charles-Henri Sanson died on July 4, 1806, and is buried in a family plot in Montmartre Cemetery in Paris.

Fictionalized accounts

- Charles-Henri Sanson is the protagonist in the historical novel "The Executioner's Heir" by Susanne Alleyn (2013).

- Charles-Henri Sanson appears as a secondary, but significant character, in the Aristide Ravel series by Susanne Alleyn

- Charles-Henri's life is heavily and rather inaccurately fictionalized in German author Hans Mahner-Mons's novel Der Kavalier von Paris (E. The Sword of Satan) (1954).

- Jim Shepard's story "Sans Farine," from his collection Like You'd Understand, Anyway (2007), presents a fictionalized autobiography of Charles-Henri Sanson.

- Charles-Henri Sanson appears as a minor but significant character in Hilary Mantel's novel A Place of Greater Safety (1992).

- Charles-Henri Sanson appears as a main character in Paola Barbato's comic book "Il boia di Parigi" (The Executioner of Paris), the first volume in "Le Storie" edition.

- Charles-Henri Sanson appears as a main character in Sakamoto Shinichi's 2013 manga titled Innocent.

- Charles-Henri Sanson appears as a summonable Servant for the main character in Fate/Grand Order under the Assassin class.

- Charles-Henri Sanson appears as a minor character played by Christopher Lee in two-part film La Révolution française (1989).[14]

Further reading

- Robert Christophe: Les Sanson, bourreaux de père en fils, pendant deux siècles. Arthème Fayard, Paris 1960.

- Guy Lenôtre: Die Guillotine und die Scharfrichter zur Zeit der französischen Revolution. Kadmos, Berlin 1996. ISBN 3-931659-03-8

- Hans-Eberhard Lex: Der Henker von Paris. Charles-Henri Sanson, die Guillotine, die Opfer. Rasch u. Röhring, Hamburg 1989. ISBN 3-89136-242-0

- Chris E. Paschold, Albert Gier (Hrsg.): Der Scharfrichter - Das Tagebuch des Charles-Henri Sanson (Aus der Zeit des Schreckens 1793-1794). Insel-Verlag, Frankfurt/M. 1989; ISBN 3-458-16048-5

- Henri Sanson: Tagebücher der Henker von Paris. 1685-1847. Erster und zweiter Band in einer Ausgabe, hrsg. v. Eberhard Wesemann u. Knut-Hannes Wettig. Nikol, Hamburg 2004. ISBN 3-933203-93-7

- Honoré de Balzac: Un épisode sous la Terreur (fiction)

References

- ↑ Sargent, Lucius Manlius (1855); Dealings with the Dead, Vol. II, Dutton & Wentworth, MA, USA; p.635.

- ↑ Croker, John Wilson (1857); Essays on the early period of the French Revolution, John Murray, London; p.570 ff. with enumerated list of all six generations of Sansons.

- ↑ Jordan, David P. (2004). "The King's Trial: The French Revolution vs. Louis XVI". Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 215.

- ↑ Andress, David (2005). "The Terror: The Merciless War for Freedom in Revolutionary France". New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 147.

- ↑ Andress, David (2005). "The Terror: The Merciless War for Freedom in Revolutionary France". New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 147.

- ↑ Croker (1857); p.534 ff. Croker includes the full text of Sanson's "Memorandum of Observations on the Execution of Criminals by Beheading.".

- ↑ Gerould, Daniel (1992); Guillotine: Its Legend and Lore; Blast, NY; ISBN 0-922233-02-0. See p.14. |"[I]n March, 1792... he [Sanson] explained the need for a new instrument. His sword grew blunt after each decapitation, (etc.)". See also Croker (1857), p.534: "It is to be considered [wrote Sanson] that when there shall be several criminals to execute at the same time, the terror that such an execution presents... [would be] an invincible obstacle...."

- ↑ Gerould (1992). See pp.23-24: "The guillotine was first tested on April 17, 1792, at the famous Bicêtre Hospital... Accompanied by his two brothers and son, Sanson supervised the proceedings."

- ↑ National Museum of Crime and Punishment, Washington, DC. Retrieved August 2010: "...[I]n 1792, Nicholas-Jacques Pelletier became the first person to be put to death with a guillotine."

- ↑ Roche, Katherine (1881). ""Hereditary Hangmen"". The Irish Monthly. 9: 28 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Roche, Katherine (1881). ""Hereditary Hangmen"". The Irish Monthly. 9: 29 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Croker (1857). See p.556: "It was in exhibiting one of these heads to the people that the younger Sanson [Gabriel] fell off the scaffold and was killed." See also p.570: "He [Charles-Henri] had two sons, but one of these was killed on August 27, 1792, by falling from the scaffold...."

- ↑ Leonard Cottrell, Madame Tussaud, Evans Brothers Limited, 1952, p. 142-43.

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0098238/

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Memoirs of Henry Sansons (English)

- Sanson Family article on FR.Wikipedia (French)