Chagres and Fort San Lorenzo

| Chagres | |

|---|---|

| Depopulated | |

|

The current ruins of Fort San Lorenzo date from the 1750s.[2] | |

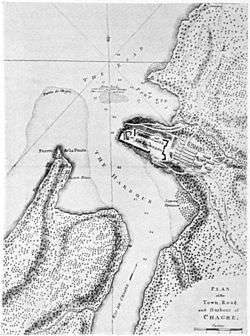

Map of Chagres and Fort San Lorenzo in about 1739 | |

Chagres Location in Panama | |

| Coordinates: 9°19′20″N 80°00′10″W / 9.32222°N 80.00278°WCoordinates: 9°19′20″N 80°00′10″W / 9.32222°N 80.00278°W | |

| Country | Panama |

| Province | Colón |

| District | Chagres |

| Established | 1680s |

| Depopulated | 1916 |

| Fort San Lorenzo | |

|---|---|

|

Fuerte de San Lorenzo, Castillo de San Lorenzo de Chagres | |

| Chagres, Panama | |

|

Fort San Lorenzo. 2009 | |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1587 - 1750 |

| Built by | Spain |

| Official name | Fortifications on the Caribbean Side of Panama: Portobelo-San Lorenzo |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iv |

| Designated | 1980 (4th session) |

| Reference no. | 135 |

| State Party | Panama |

| Region | Latin America and the Caribbean |

Chagres (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈtʃaɣɾes]), once the chief Atlantic port on the isthmus of Panama, is now an abandoned village at the historical site of Fort San Lorenzo. The fort's ruins and the village site are located about 8 miles (13 km) west of Colón, on a promontory overlooking the mouth of the Chagres River.

16th and 17th centuries: Discovery and fortification

In 1502, during his fourth and final voyage, Christopher Columbus discovered the Chagres River.

By 1534, the Monarchy of Spain had, following its conquest of Peru, established a rainy-season gold route over the isthmus of Panama—Las Cruces Trail—most of which consisted of the Chagres River. The trail connected the Pacific port of Panama City to the mouth of the Chagres, from whence Peru's plunder would sail to Spain's storehouses in the leading Atlantic ports of the isthmus: Nombre de Dios, at first; and, later, Portobelo. (The dry-season, overland route—the Camino Real—connected Panama City with those ports directly.)[3]

Attracted to the treasure, pirates began attacking Panama's coast around 1560. To protect the Atlantic terminus of Las Cruces Trail, Spain built Fort San Lorenzo at the Chagres River's mouth. From 1587 to 1599, the fortifications evolved into a sea-level battery.[4]

In 1670, buccaneer Henry Morgan ordered an attack that left Fort San Lorenzo in ruins. He invaded Panama City the following year, using San Lorenzo as his base of operations.

In the 1680s, the Spanish constructed a new fort 80 feet (24 m) above the water. Set on a cliff overlooking the entrance to the harbor, the fort was protected on the landward side by a dry moat with a drawbridge. During this time, the town of Chagres was established under the protection of the fort.[5]

18th and 19th centuries: Decline and rebirth

In 1739 and 1740, British Admiral Edward Vernon attacked the Spanish fortifications at Portobelo and Chagres. With the destruction of Portobelo's fort, Spain abandoned trade there, instead strengthening its fortifications at Chagres,[6] and, upstream, Gatun.[4] With the decline of Portobelo, Chagres surpassed it as the chief Atlantic port of the isthmus.[7]

By the middle of the 18th century, however, the Spanish had largely abandoned both of the old trails over the isthmus, preferring to sail around the tip of South America at Cape Horn. For over a century, Fort San Lorenzo was used as a prison.[4]

The 1848 finding of gold in California stimulated new vitality at the mouth of the Chagres River. Westbound prospectors who preferred to avoid crossing the "Great American Desert" or rounding Cape Horn would follow the old path of the Las Cruces Trail, beginning their transcontinental journey at "Yankee Town"[8] or "Yanqui Chagres"[9]—the wild-west boomtown that sprang up on the bank opposite the original village and fortress.

The rebirth of Chagres' importance was short-lived. Although the advent of steamboat service on the Chagres River had, by 1853, shortened the time required to cross the isthmus from several days to about twelve hours, the 1855 completion of the Panama Railway further reduced the transcontinental travel time to about three hours.[10] As a result, the railway’s Atlantic terminus, Colón, became Panama's Atlantic port, and Chagres receded from importance.[7]

20th century: Canal Zone to Protected Area

The construction of the Panama Canal, completed in 1914, required the construction of the massive Gatun Dam, about 7.2 miles (11.6 km) upriver from Chagres, permanently sealing off the river from inland trade.

Although Chagres fell outside the original boundary of the Panama Canal Zone, that zone expanded in 1916 to include the mouth of Chagres River. The town of Chagres—which, by then, had only 96 houses and 400 to 500 inhabitants—was then "depopulated," and its former residents were resettled to Nuevo Chagres, located about 8.2 miles (13.2 km) to the southwest, along the coast.[11]

Fort San Lorenzo has been designated as government-protected since 1908. Currently, the ruins of Fort San Lorenzo and the Chagres village site are contained within the 30,000 acres (12,000 ha) of the San Lorenzo Protected Area, all former Canal Zone territory.[12]

In 1980, UNESCO declared Fort San Lorenzo, together with the fortified town of Portobelo about 30 miles (48 km) to the northeast, to be a World Heritage Site under the name, "Fortifications on the Caribbean Side of Panama." The organization describes the fortifications as follows: "Magnificent examples of 17th- and 18th-century military architecture, these Panamanian forts on the Caribbean coast form part of the defence system built by the Spanish Crown to protect transatlantic trade."[13]

Images

In fiction

Chagres features prominently in The Adventures & Brave Deeds Of The Ship's Cat On The Spanish Maine: Together With The Most Lamentable Losse Of The Alcestis & Triumphant Firing Of The Port Of Chagres, a children's book by Richard Adams.

See also

- Chagres District—a district within the Colón Province

- Chagres National Park

- Chagres River

- Nuevo Chagres—the capital of Chagres District

- Portobelo—part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Castillo San Lorenzo. |

- ↑ Weaver and Bauer, p. 88

- ↑ Weaver and Bauer, p. 88

- ↑ Weaver and Bauer, pp. 14-16

- 1 2 3 Weaver and Bauer, p. 16

- ↑ Weaver and Bauer, pp. 16-17

- ↑ Minter, p. 189

- 1 2

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Chagres". Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 800–801.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Chagres". Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 800–801. - ↑ Weaver and Bauer, p. 17

- ↑ Minter, p. 238

- ↑ Minter, pp. 210-11, 219, 281

- ↑ Weaver and Bauer, p. 3

- ↑ Weaver and Bauer, pp. 2, 4

- ↑ "Fortifications on the Caribbean Side of Panama: Portobelo-San Lorenzo". UNESCO. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

References

- Minter, John Easter (1948), The Chagres: River of Westward Passage, Rivers of America, New York: Rinehart & Company

- Weaver, Peter L.; Bauer, Gerald P. (April 2004), The San Lorenzo Protected Area: A Summary of Cultural and Natural Resources (PDF), United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry, retrieved 12 December 2012