Ceratopsidae

| Ceratopsids Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, 84–66 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Triceratops prorsus skeleton, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. | |

| | |

| Centrosaurus nasicornus skeleton, Palaeontological Museum Munich | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | †Ornithischia |

| Superfamily: | †Ceratopsoidea |

| Family: | †Ceratopsidae Marsh, 1890 |

| Subgroups | |

| Synonyms | |

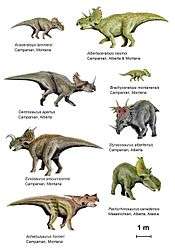

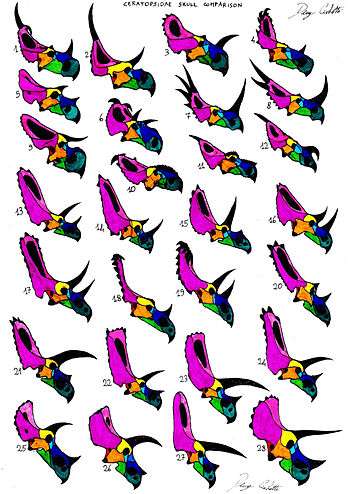

Ceratopsidae (sometimes spelled Ceratopidae) is a speciose group of marginocephalian dinosaurs including Triceratops and Styracosaurus. All known species were quadrupedal herbivores from the Upper Cretaceous, mainly of Western North America (though Sinoceratops is known from Asia)[1] and are characterized by beaks, rows of shearing teeth in the back of the jaw, and elaborate horns and frills. The group is divided into two subfamilies. The Ceratopsinae or Chasmosaurinae are generally characterized by long, triangular frills and well-developed brow horns. The Centrosaurinae had well-developed nasal horns or nasal bosses, shorter and more rectangular frills, and elaborate spines on the back of the frill.

These horns and frills show remarkable variation and are the principal means by which the various species have been recognized. Their purpose is not entirely clear. Defense against predators is one possible purpose – although the frills are comparatively fragile in many species – but it is more likely that, as in modern ungulates, they may have been secondary sexual characteristics used in displays or for intraspecific combat. The massive bosses on the skulls of Pachyrhinosaurus and Achelousaurus resemble those formed by the base of the horns in modern musk oxen, suggesting that they may have butted heads. Centrosaurines have frequently been found in massive bone beds with few other species present, suggesting that the animals might have lived in large herds.

Paleobiology

Behavior

Fossil deposits dominated large numbers of ceratopsids from individual species suggest that these animals were at least somewhat social.[2] However, the exact nature of ceratopsid social behavior has historically been controversial.[3] In 1997, Lehman argued that the aggregations of many individuals preserved in bonebeds originated as local "infestations" and compared them to similar modern occurrences in crocodiles and tortoises.[3] Other authors, such as Scott D. Sampson, interpret these deposits as the remains of large "socially complex" herds.[3]

Modern animals with mating signals as prominent as the horns and frills of ceratopsians tend to form these kinds of large, intricate associations.[4] Sampson found in previous work that the centrosaurine ceratopsids did not achieve fully developed mating signals until nearly fully grown.[5] He finds commonality between the slow growth of mating signals in centrosaurines and the extended adolescence of animals whose social structures are ranked hierarchies founded on age-related differences.[5] In these sorts of groups young males are typically sexually mature for several years before actually beginning to breed, when their mating signals are most fully developed.[6] Females, by contrast do not have such an extended adolescence.[6]

Other researchers who support the idea of ceratopsid herding have speculated that these associations were seasonal.[7] This hypothesis portrays ceratopsids as living in small groups near the coasts during the rainy season and inland with the onset of the dry season.[7] Support for the idea that ceratopsids formed herds inland comes from the greater abundance of bonebeds in inland deposits than coastal ones. The migration of ceratopsids away from the coasts may have represented a move to their nesting grounds.[7] Many African herding animals engage in this kind of seasonal herding today.[7] Herds would also have afforded some level of protection from the chief predators of ceratopsids, tyrannosaurids.[8]

Diet

Ceratopsids were adapted to processing high-fiber plant material with their highly derived dental batteries.[9] They may have utilized fermentation to break down plant material with a gut microflora.[9] Mallon et al. (2013) examined herbivore coexistence on the island continent of Laramidia, during the Late Cretaceous. It was concluded that ceratopsids were generally restricted to feeding on vegetation at, or below, the height of 1 meter.[10]

Physiology

Ceratopsians probably had the "low mass-specific metabolic rat[e]" typical of large bodied animals.[9]

Sexual dimorphism

According to Scott D. Sampson, if ceratopsids were to have sexual dimorphism modern ecological analogues suggest it would be in their mating signals like horns and frills.[11] No convincing evidence for sexual dimorphism in body size or mating signals is known in ceratopsids, although was present in the more primitive ceratopsian Protoceratops andrewsi whose sexes were distinguishable based on frill and nasal prominence size.[11] This is consistent with other known tetrapod groups where midsized animals tended to exhibit markedly more sexual dimorphism than larger ones.[12] However, if there were sexually dimorphic traits they may have been soft tissue variations like colorations or dewlaps that would not have been preserved as fossils.[12]

Evolution

Scott D. Sampson has compared the evolution of ceratopsids to that of some mammal groups: both were rapid from a geological perspective and precipitatied the simultaneous evolution of large body size, derived feeding structures, and "varied hornlike organs."[3]

Paleoecology

The chief predators of ceratopsids were tyrannosaurids.[8]

There is evidence for an aggressive interaction between a Triceratops and a Tyrannosaurus in the form of partially healed tyrannosaur tooth marks on a Triceratops brow horn and squamosal (a bone of the neck frill); the bitten horn is also broken, with new bone growth after the break. It is not known what the exact nature of the interaction was, though: either animal could have been the aggressor.[13] Since the Triceratops wounds healed, it is most likely that the Triceratops survived the encounter and managed to overcome the Tyrannosaurus. Paleontologist Peter Dodson estimates that in a battle against a bull Triceratops, the Triceratops had the upper hand and would successfully defend itself by inflicting fatal wounds to the Tyrannosaurus using its sharp horns.[14]

Classification

The clade Ceratopsidae was in 1998 defined by Paul Sereno as the group including the last common ancestor of Pachyrhinosaurus and Triceratops; and all its descendants.[15] In 2004, it was by Peter Dodson defined to include Triceratops, Centrosaurus, and all descendants of their most recent common ancestor.[16]

- Family Ceratopsidae

- Subfamily Centrosaurinae

- Albertaceratops - (Alberta, Canada & ?Montana, USA)

- Avaceratops - (Montana, USA)

- Brachyceratops - (Montana, USA & Alberta, Canada)

- Centrosaurus - (Alberta, Canada)

- Coronosaurus - (Alberta, Canada)

- Diabloceratops - (Utah, USA)

- Machairoceratops[17] - (Utah, USA)

- Monoclonius - (Montana, USA & Alberta, Canada)

- Nasutoceratops - (Utah, USA)

- Rubeosaurus - (Montana, USA)

- Spinops - (Alberta, Canada)

- Styracosaurus - (Alberta, Canada & Montana, USA)

- Xenoceratops - (Alberta, Canada)

- Tribe Pachyrhinosaurini

- Achelousaurus - (Montana, USA)

- Einiosaurus - (Montana, USA)

- Pachyrhinosaurus- (Alberta, Canada & Alaska, USA)

- Sinoceratops - (Shandong, China)

- Subfamily Ceratopsinae

- Ceratops - (Montana, USA & Alberta, Canada)

- Subfamily Chasmosaurinae

- Agathaumas - (Wyoming, USA)

- Agujaceratops - (Texas, USA)

- Anchiceratops - (Alberta, Canada)

- Arrhinoceratops - (Alberta, Canada)

- Chasmosaurus - (Alberta, Canada)

- Coahuilaceratops - (Coahuila, Mexico)

- ? Dysganus - (Montana, USA)

- Judiceratops - (Montana, USA)

- Kosmoceratops - (Utah, USA)

- Medusaceratops - (Montana, USA)

- Mojoceratops - (Alberta & Saskatchewan, Canada)

- Pentaceratops - (New Mexico, USA)

- ? Polyonax - (Colorado, USA)

- Spiclypeus[18] - (Montana, USA)

- Utahceratops - (Utah, USA)

- Vagaceratops - (Alberta, Canada)

- Tribe Triceratopsini

- Eotriceratops - (Alberta, Canada)

- Nedoceratops - (Wyoming, USA)

- Ojoceratops - (New Mexico, USA)

- Regaliceratops - (Alberta, Canada)

- Tatankaceratops - (South Dakota, USA)

- Titanoceratops - (New Mexico, USA)

- Torosaurus - (Wyoming, Montana, South Dakota, North Dakota, & Utah, USA & Saskatchewan, Canada)

- Triceratops - (Montana & Wyoming, USA & Saskatchewan & Alberta, Canada)

- Subfamily Centrosaurinae

See also

References

- Dodson, P. (1996). The Horned Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, pp. xiv-346

- Dodson, P., & Currie, P. J. (1990). "Neoceratopsia." 593-618 in Weishampel, D. B., Dodson, P., & Osmólska, H. (eds.), 1990: The Dinosauria. University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, Oxford, 1990 xvi-733.

- Sampson, S. D., 2001, Speculations on the socioecology of Ceratopsid dinosaurs (Orinthischia: Neoceratopsia): In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, pp. 263–276.

Footnotes

- ↑ Xu, X., Wang, K., Zhao, X. & Li, D. (2010). "First ceratopsid dinosaur from China and its biogeographical implications". Chinese Science Bulletin. 55: 1631–1635. doi:10.1007/s11434-009-3614-5.

- ↑ "Abstract," Sampson (2001); page 263.

- 1 2 3 4 "Introduction," Sampson (2001); page 264.

- ↑ "Ceratopsid Socioecology," Sampson (2001); pages 267-268.

- 1 2 "Retarded Growth of Mating Signals," Sampson (2001); page 270.

- 1 2 "Sociological Correlates in Extant Vertebrates," Sampson (2001); page 265.

- 1 2 3 4 "Resource Exploitation and Habitat," Sampson (2001); page 269.

- 1 2 "Predation Pressure," Sampson (2001); page 272.

- 1 2 3 "Resource Exploitation and Habitat," Sampson (2001); page 268.

- ↑ Mallon, Jordan C; David C Evans; Michael J Ryan; Jason S Anderson (2013). [tp://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1472-6785-13-14 "Feeding height stratification among the herbivorous dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation (upper Campanian) of Alberta, Canada"]. BMC Ecology. 13: 14. doi:10.1186/1472-6785-13-14. PMC 3637170

. PMID 23557203.

. PMID 23557203. - 1 2 "Sexual Dimorphism," Sampson (2001); page 269.

- 1 2 "Sexual Dimorphism," Sampson (2001); page 270.

- ↑ Happ, John; Carpenter, Kenneth (2008). "An analysis of predator–prey behavior in a head-to-head encounter between Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops". In Carpenter, Kenneth; and Larson, Peter E. (editors). Tyrannosaurus rex, the Tyrant King (Life of the Past). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 355–368. ISBN 0-253-35087-5.

- ↑ Dodson, Peter, The Horned Dinosaurs, Princeton Press. p.19

- ↑ Sereno, P.C. (1998). "A rationale for phylogenetic definitions, with application to the higher-level taxonomy of Dinosauria". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Abhandlungen. 210: 41–83.

- ↑ Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka, eds. (2004). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ↑ http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0154403

- ↑ http://www.livescience.com/54788-new-frilly-necked-dinosaur-identified.html