Centum and satem languages

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe East-Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe South-Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians Europe East-Asia Europe Indo-Aryan Iranian |

|

Religion and mythology

Indian Iranian Other Europe |

Languages of the Indo-European family are classified as either centum languages or satem languages according to how the dorsal consonants (sounds of "K" and "G" type) of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) developed. An example of the different developments is provided by the words for "hundred" found in the early attested Indo-European languages. In centum languages, they typically began with a /k/ sound (Latin centum was pronounced with initial /k/), but in satem languages, they often began with /s/ (the example satem comes from the Avestan language of Zoroastrian scripture).

The table below shows the traditional reconstruction of the PIE dorsal consonants, with three series, but according to some more recent theories there may actually have been only two series or three series with different pronunciations from those traditionally ascribed. In centum languages, the palatovelars, which included the initial consonant of the "hundred" root, merged with the plain velars. In satem languages, they remained distinct, and the labiovelars merged with the plain velars.[1]

| *kʷ, | *gʷ, | *gʷʰ | (labiovelars) | merged in satem languages | |

| merged in centum languages | *k, | *g, | *gʰ | (plain velars) | |

| *ḱ, | *ǵ, | *ǵʰ | (palatovelars) | assibilated in satem languages |

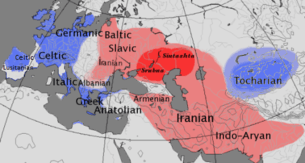

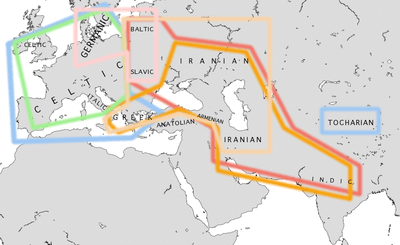

The centum–satem division forms an isogloss in synchronic descriptions of Indo-European languages. It is not thought that the Proto-Indo-European language split first into centum and satem branches from which all the centum and all the satem languages, respectively, would have derived. Such a division is made particularly unlikely by the discovery that while the satem group lies generally to the east and the centum group to the west, the most eastward of the known IE language branches, Tocharian, is centum.[2] Each of the ten branches of the Indo-European family independently developed its status as a centum or satem language.

Centum languages

The canonical centum languages of the Indo-European family are the "western" branches: Hellenic, Celtic, Italic and Germanic. They merged Proto-Indo-European palatovelars and plain velars, yielding plain velars only ("centumisation") but retained the labiovelars as a distinct set.[1]

The Anatolian branch likely falls outside the centum–satem dichotomy; for instance, Luwian indicates that all three dorsal consonant rows survived separately in Proto-Anatolian.[3] The centumisation observed in Hittite is therefore assumed to have occurred only after the breakup of Proto-Anatolian.[4]

While Tocharian is generally regarded as a centum language,[5] it is a special case, as it has merged all three of the PIE dorsal series (originally nine separate consonants) into a single phoneme, *k. According to some scholars, that complicates the classification of Tocharian within the centum–satem model.[6] However, as Tocharian has replaced some Proto-Indo-European labiovelars with the labiovelar-like, non-original sequence *ku; it has been proposed that labiovelars remained distinct in Proto-Tocharian, which places Tocharian in the centum group (assuming that Proto-Tocharian lost palatovelars while labiovelars were still phonemically distinct).[5]

In the centum languages, PIE roots reconstructed with palatovelars developed into forms with plain velars. For example, in the PIE root *ḱm̥tóm, "hundred", the initial palatovelar *ḱ became a plain velar /k/, as in Latin centum (which was originally pronounced with /k/ in spite of various modernised pronunciations with /s/, for example), Greek (he)katon, Welsh cant, Tocharian B kante. In the Germanic languages, the /k/ developed regularly by Grimm's law to become /h/, as in the English hund(red).

Centum languages also retained the distinction between the PIE labiovelar row (*kʷ, *gʷ, *gʷʰ) and the plain velars. Historically, it was unclear whether the labiovelar row represented an innovation by a process of labialisation, or whether it was inherited from the parent language (but lost in the satem branches); current mainstream opinion favours the latter possibility. Labiovelars as single phonemes (for example, /kʷ/) as opposed to biphonemes (for example, /kw/) are attested in Greek (the Linear B q- series), Italic (Latin qu), Germanic (Gothic hwair ƕ and qairþra q) and Celtic (Ogham ceirt Q) (in the P-Celtic languages /kʷ/ developed into /p/; a similar development sometimes took place in Greek). The boukólos rule, however, states that a labiovelar reduces to a plain velar when it occurs next to *u or *w.

The centum–satem division refers to the development of the dorsal series at the time of the earliest separation of Proto-Indo-European into the proto-languages of its individual daughter branches. It does not apply to any later analogous developments within any individual branch. For example, the conditional palatalization of Latin /k/ to /s/ in some Romance languages (which means that modern French cent is pronounced with initial /s/) is satem-like, as is the merger of *kʷ with *k in the Gaelic languages; such later changes do not affect the classification of the languages as centum.

Satem languages

The satem languages belong to the "eastern" sub-families, especially Indo-Iranian and Balto-Slavic (but not Tocharian). It lost the labial element of Proto-Indo-European labiovelars and merged them with plain velars, but the palatovelars remained distinct and typically came to be realised as sibilants.[7] That set of developments, particularly the assibilation of palatovelars, is referred to as satemisation.

The Albanian and Armenian branches are also classified as satem, but some linguists claim that they show evidence of separate treatment of all three dorsal consonant rows and so may not have merged the labiovelars with the plain velars, unlike the canonical satem branches.[8] In Armenian, some assert that /kʷ/ is distinguishable from /k/ before front vowels,[9] but in Albanian, it has been claimed that /kʷ/ and /gʷ/ are distinguishable from /k/ and /g/ before front vowels[10] Such "incomplete satemisation" may also be evidenced by remnants of labial elements from labiovelars in Balto-Slavic, including Lithuanian ungurys "eel" < *angʷi- and dygus "pointy" < *dʰeigʷ-. A few examples are also claimed in Indo-Iranian, such as Sanskrit guru "heavy" < *gʷer-, kulam "herd" < *kʷel-, but they may instead be secondary developments, as in the case of kuru "make" < *kʷer- in which it is clear that the ku- group arose in post-Rigvedic language. It is also asserted that in Sanskrit and Balto-Slavic, in some environments, resonant consonants (denoted by /R/) become /iR/ after plain velars but /uR/ after labiovelars.

In the satem languages, the reflexes of the presumed PIE palatovelars are typically fricative or affricate consonants, articulated further forward in the mouth. For example, the PIE root *ḱm̥tóm, "hundred", the initial palatovelar normally became a sibilant [s] or [ʃ], as in Avestan satem, Persian sad, Sanskrit śatam, Latvian simts, Lithuanian šimtas, Old Church Slavonic sъto. Another example is the Slavic prefix sъ(n)- ("with"), which appears in Latin, a centum language, as co(n)-; conjoin is cognate with Russian soyuz ("union"). An [s] is found for PIE *ḱ in such languages as Latvian, Avestan, Russian and Armenian, but Lithuanian and Sanskrit have [ʃ] (š in Lithuanian, ś in Sanskrit transcriptions). For more reflexes, see the phonetic correspondences section below; note also the effect of the ruki sound law.

Assibilation of velars in certain phonetic environments is a common phenomenon in language development (compare, for example, the initial sounds in French cent and Spanish ciento, which are fricatives even though they derive from Latin /k/). Consequently, it is sometimes hard to establish firmly the languages that were part of the original satem diffusion and the ones affected by secondary assibilation later. While extensive documentation of Latin and Old Swedish, for example, shows that the assibilation found in French and Swedish were later developments, there are not enough records of Dacian and Thracian to settle conclusively when their satem-like features originated. Extensive lexical borrowing, such as Armenian from Iranian, may also add to the difficulty. The status of Armenian as a satem language as opposed to a centum language with secondary assibilation rests on the evidence of a very few words.

History of concept

Schleicher's single guttural row

August Schleicher, an early Indo-Europeanist, in Part I, "Phonology", of his major work, the 1871 Compendium of Comparative Grammar of the Indogermanic Language, published a table of original momentane Laute, or "stops", which has only a single velar row, *k, *g, *gʰ, under the name of Gutturalen.[11][12] He identifies four palatals (*ḱ, *ǵ, *ḱʰ, *ǵʰ) but hypothesises that they came from the gutturals along with the nasal *ń and the spirant *ç.[13]

Brugmann's labialized and unlabialized language groups

Karl Brugmann, in his 1886 work Outline of Comparative Grammar of the Indogermanic Language (Grundriss...), promotes the palatals to the original language, recognising two rows of Explosivae, or "stops", the palatal (*ḱ, *ǵ, *ḱʰ, *ǵʰ) and the velar (*k, *g, *kʰ, *gʰ),[14] each of which was simplified to three articulations even in the same work.[15] In the same work, Brugmann notices among die velaren Verschlusslaute, "the velar stops", a major contrast between reflexes of the same words in different daughter languages. In some l, the velar is marked with a u-Sprache, "u-articulation", which he terms a Labialisierung, "labialization", in accordance with the prevailing theory that the labiovelars were velars labialised by combination with a u at some later time and were not among the original consonants. He thus divides languages into die Sprachgruppe mit Labialisierung[16] and die Sprachgruppe ohne Labialisierung, "the language group with (or without) labialization", which basically correspond to what would later be termed the centum and satem groups:[17]

For words and groups of words, which do not appear in any language with labialized velar-sound [the "pure velars"], it must for the present be left undecided whether they ever had the u-afterclap.

The doubt introduced in that passage suggests he already suspected the "afterclap" u was not that but was part of an original sound.

Von Bradke's centum and satem groups

In 1890, Peter von Bradke published Concerning Method and Conclusions of Aryan (Indogermanic) Studies, in which he identified the same division (Trennung) as did Brugmann, but he defined it in a different way. He said that the original Indo-Europeans had two kinds of gutturaler Laute, "guttural sounds" the gutturale oder velare, und die palatale Reihe, "guttural or velar, and palatal rows", each of which were aspirated and unaspirated. The velars were to be viewed as gutturals in an engerer Sinn, "narrow sense". They were a reiner K-Laut, "pure K-sound". Palatals were häufig mit nachfolgender Labialisierung, "frequently with subsequent labialization". The latter distinction led him to divide the palatale Reihe into a Gruppe als Spirant and a reiner K-Laut, typified by the words satem and centum respectively.[18] Later in the book[19] he speaks of an original centum-Gruppe, from which on the north of the Black and Caspian Seas the satem-Stämmen, "satem tribes", dissimilated among the Nomadenvölker or Steppenvölker, distinguished by further palatalization of the palatal gutturals.

Brugmann's identification of labialized and centum

By the 1897 edition of Grundriss, Brugmann (and Delbrück) had adopted Von Bradke's view: "The Proto-Indo-European palatals... appear in Greek, Italic, Celtic and Germanic as a rule as K-sounds, as opposed to in Aryan, Armenian, Albanian, Balto-Slavic, Phrygian and Thracian... for the most part sibilants."[20]

There was no more mention of labialized and non-labialized language groups after Brugmann changed his mind regarding the labialized velars. The labio-velars now appeared under that name as one of the five rows of Verschlusslaute (Explosivae) (plosives/stops), comprising die labialen V., die dentalen V., die palatalen V., die reinvelaren V. and die labiovelaren V. It was Brugmann who pointed out that labiovelars had merged into the velars in the satem group,[21] accounting for the coincidence of the discarded non-labialized group with the satem group.

Discovery of Anatolian and Tocharian

When von Bradke first published his definition of the centum and satem sound changes, he viewed his classification as "the oldest perceivable division" in Indo-European, which he elucidated as "a division between eastern and western cultural provinces (Kulturkreise)".[22] The proposed split was undermined by the decipherment of Hittite and Tocharian in the early 20th century. Both languages show no satem-like assibilation in spite of being located in the satem area.[23]

The proposed phylogenetic division of Indo-European into satem and centum "sub-families" was further weakened by the identification of other Indo-European isoglosses running across the centum–satem boundary, some of which seemed of equal or greater importance in the development of daughter languages.[24] Consequently, since the early 20th century at least, the centum–satem isogloss has been considered an early areal phenomenon rather than a true phylogenetic division of daughter languages.

Alternative interpretations

Different realisations

The actual pronunciation of the velar series in PIE is not certain. One current idea is that the "palatovelars" were in fact simple velars *[k], *[ɡ], *[ɡʰ], and the "plain velars" were pronounced farther back, perhaps as uvular consonants: *[q], *[ɢ], *[ɢʰ].[25] If labiovelars were just labialized forms of the "plain velars', they would have been pronounced *[qʷ], *[ɢʷ], *[ɢʷʰ]. The following are arguments in support of that view:

- The "palatovelar" series was the most common, and the "plain velar" was by far the least common and never occurred in any affixes. In known languages with multiple velar series, the normal velar series is usually the most common, which would imply that what have been interpreted as "palatovelars" were more probably simply velars.

- There is no evidence of any palatalisation in the early history of the velars in the centum branches, but see above for the case of Anatolian. If the "palatovelars" were in fact palatalised in PIE, there would have had to be a single, very early, uniform depalatalisation in all (and only) the centum branches. Depalatalisation is cross-linguistically far less common than is palatalisation and so is unlikely to have occurred separately in each centum branch. In any case it would almost certainly have left evidence of prior palatalization in some of the branches. (As noted above, it is not thought that the centum branches had a separate common ancestor in which the depalatalization could have occurred just once and then have been inherited.)

On the above interpretation, the split between the centum and satem groups would not have been a straightforward loss of an articulatory feature (palatalization or labialization). Instead, the uvulars *q, *ɢ, *ɢʰ (the "plain velars" of the traditional reconstruction) would have been fronted to velars across all branches. In the satem languages, it caused a chain shift, and the existing velars (traditionally "palatovelars") were shifted further forward to avoid a merger, becoming palatal: /k/ > /c/; /q/ > /k/. In the centum languages, no chain shift occurred, and the uvulars merged into the velars. The delabialisation in the satem languages would have occurred later, in a separate stage.

Only two velar series

The presence of three dorsal rows in the proto-language has been the mainstream hypothesis since at least the mid 20th century. There remain, however, several alternative proposals with just two rows in the parent language, which describe either "satemisation" or "centumisation", as the emergence of a new phonematic category rather than the disappearance of an inherited one.

Antoine Meillet (1937) proposed that the original rows were the labiovelars and palatovelars, with the plain velars being allophones of the palatovelars in some cases, such as depalatalisation before a resonant.[26] The etymologies establishing the presence of velars in the parent language are explained as artefacts of either borrowing between daughter languages or of false etymologies.

Other scholars who assume two dorsal rows in Proto-Indo-European include Kuryłowicz (1935) and Lehmann (1952), as well as Frederik Kortlandt and others.[27] The argument is that PIE had only two series, a simple velar and a labiovelar. The satem languages palatalized the plain velar series in most positions, but the plain velars remained in some environments: typically reconstructed as before or after /u/, after /s/, and before /r/ or /a/ and also before /m/ and /n/ in some Baltic dialects. The original allophonic distinction was disturbed when the labiovelars were merged with the plain velars. That produced a new phonemic distinction between palatal and plain velars, with an unpredictable alternation between palatal and plain in related forms of some roots (those from original plain velars) but not others (those from original labiovelars). Subsequent analogical processes generalised either the plain or palatal consonant in all forms of a particular root. The roots in which the plain consonant was generalized are those traditionally reconstructed as having "plain velars" in the parent language in contrast to "palatovelars".

Oswald Szemerényi (1990) considers the palatovelars as an innovation, proposing that the "preconsonantal palatals probably owe their origin, at least in part, to a lost palatal vowel" and a velar was palatalised by a following vowel subsequently lost.[28] The palatal row would therefore postdate the original velar and labiovelar rows, but Szemerényi is not clear whether that would have happened before or after the breakup of the parent-language (in a table showing the system of stops "shortly before the break-up", he includes palatovelars with a question mark after them).

Woodhouse (1998; 2005) introduced a "bitectal" notation, labelling the two rows of dorsals as k1, g1, g1h and k2, g2, g2h. The first row represents "prevelars", which developed into either palatovelars or plain velars in the satem group but just into plain velars into the centum group; the second row represents "backvelars", which developed into either labiovelars or plain velars in the centum group but just plain velars in the satem group.[29]

The following are arguments that have been listed in support of a two-series hypothesis:[30]

- The plain velar series is statistically rarer than the other two, is almost entirely absent from affixes and appears most often in certain phonological environments (described in the next point).

- The reconstructed velars and palatovelars occur mostly in complementary distribution (velars before *a, *r and after *s, *u; palatovelars before *e, *i, *j, liquid/nasal/*w+*e/*i and before o in o-grade forms by generalization from e-grade).

- It is unusual in general for palatovelars to move backwards rather than the reverse (but that problem might simply be addressed by assuming three series with different realizations from the traditional ones, as described above).

- In most languages in which the "palatovelars" produced fricatives, other palatalisation also occurred, implying that it was part of a general trend;

- The centum languages are not contiguous, and there is no evidence of differences between dialects in the implementation of centumization (but there are differences in the process of satemisation: there can be pairs of satemized and non-satemized velars within the same language, there is evidence of a former labiovelar series in some satem languages and different branches have different numbers and timings of satemization stages). This makes a "centumisation" process less likely, implying that the position found in the centum languages was the original one.

- Alternations between plain velars and palatals are common in a number of roots across different satem languages, but the same root appears with a palatal in some languages but a plain velar in others (most commonly Baltic or Slavic, occasionally Armenian but rarely or never the Indo-Iranian languages). That is consistent with the analogical generalisation of one or another consonant in an originally-alternating paradigm but difficult to explain otherwise.

- The claim that in late PIE times, the satem languages (unlike the centum languages) were in close contact with each other is confirmed by independent evidence: the geographical closeness of current satem languages and certain other shared innovations (the ruki sound law and early palatalization of velars before front vowels).

Arguments in support of three series:

- Many instances of plain velars occur in roots that have no evidence of any of the putative environments that trigger plain velars and no obvious mechanism for the plain velar to have come in contact with any such environment; as a result, the comparative method requires three series to be reconstructed.

- Albanian and Armenian are said to retain three series (that is disputed, and it is pointed out that this does not falsify an original two-series hypothesis, as they may have been satem languages in which the labiovelars failed to merge);

- Evidence from the Anatolian language Luwian attests a three-way velar distinction *ḱ > z (probably [ts]); *k > k; *kʷ > ku (probably [kʷ]).[31] There is no evidence of any connection between Luwian and any satem language (labiovelars are still preserved, the ruki sound law is absent) and the Anatolian branch split off very early from PIE. The three-way distinction must be reconstructed for the parent language. (That is a strong argument in favor of the traditional three-way system; in response, proponents of the two-way system have attacked the underlying evidence by claiming that it "hinges upon especially difficult or vague or otherwise dubious etymologies" (such as Sihler 1995).) Melchert originally claimed that the change *ḱ > z was unconditional and subsequently revised the assertion to a conditional change occurring only before front vowels, /y/, or /w/; however, that does not fundamentally alter the situation, as plain-velar *k apparently remains as such in the same context. Melchert also asserts, contrary to Sihler, the etymological distinction between *ḱ and *k in the relevant positions is well-established.[32]

- According to Ringe (2006), there are root constraints that prevent the occurrence of a "palatovelar" and labiovelar or two "plain velars", in the same root, but they do not apply to roots containing, for example, a palatovelar and a plain velar.

- The centum change could have occurred independently in multiple centum subgroups (at the very least, Tocharian, Anatolian and Western IE), as it was a phonologically natural change, given the possible interpretation of the "palatovelar" series as plain-velar and the "plain velar" series as back-velar or uvular (see above). Given the minimal functional load of the plain-velar/palatovelar distinction, if there was never any palatalisation in the IE dialects leading to the centum languages, there is no reason to expect any palatal residues. Furthermore, it is phonologically entirely natural for a former plain-velar vs. back-velar/uvular distinction to have left no distinctive residues on adjacent segments.

Phonetic correspondences in daughter languages

The following table summarizes the outcomes of the reconstructed PIE palatals and labiovelars in the various daughter branches, both centum and satem. (The outcomes of the "plain velars" can be assumed to be the same as those of the palatals in the centum branches and those of the labiovelars in the satem branches.)

| PIE | *ḱ | *ǵ | *ǵʰ | *kʷ | *gʷ | *gʷʰ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Celtic | k | g | g | kw, p[* 1] | b | gw |

| Italic | k | g | g, h[* 2] | kw, p[* 3] | gw, v, b[* 3] | f, v |

| Venetic | k | g | h | kw | ? | ? |

| Hellenic | k | g | kh | p, t, k[* 4] | b, d, g[* 4] | ph, kh, th[* 4] |

| Albanian | s,[* 5] (k) | z,[* 5] (g) | z,[* 5] (d) | k, s | g, z | g, z |

| Illyrian | s[* 5] | z[* 5] | z[* 5] | ? | ? | ? |

| Thracian | s[* 5] | z[* 5] | z[* 5] | k, kh | g, k | g |

| Armenian | s | c | dz | kh | k | g |

| Phrygian | k[* 6] | g[* 6] | g, k | k | b | g |

| Germanic | h | k | g ~ ɣ[* 7] | hw | kw | gw[* 8] ~ w[* 7] |

| Slavic | s | z | z | k | g | g |

| Baltic | š | ž | ž | k | g | g |

| Indic | ç[* 9] | dž | h[* 10] | k, č | g | gh |

| Iranian | s | z | z[* 10] | k, č | g | g |

| Anatolian | k[* 11] | g[* 12] | g[* 12] | kw | gw[* 13] | gw[* 13] |

| Tocharian | k | k | k | k, kw | k, kw | k, kw |

- ↑ Within Celtic, the "p-Celtic" and "q-Celtic" branches have different reflexes of PIE *kʷ: *ekwos → ekwos, epos. The Brythonic and Lepontic languages are P-Celtic, Goidelic and Celtiberian are Q-Celtic and different dialects of Gaulish had different realisations.

- ↑ PIE *ǵʰ → Latin /h/ or /ɡ/, depending on its position in the word, and → Osco-Umbrian *kh → /h/.

- 1 2 PIE *kʷ and *gʷ developed differently in the two Italic subgroups: /kw/, /w/ in Latin (*kwis → quis), and /p/, /b/ in Osco-Umbrian (*kwis → pis).

- 1 2 3 PIE *kʷ, *gʷ, *gʷʰ have three reflexes in Greek dialects such as Attic and Doric:

- /t, d, th/ before /e, é, i/ (IE *kʷis → Greek tis)

- /k, ɡ, kh/ before /u/ (IE *wl̥kʷos → Greek lukos)

- /p, b, ph/ before /a, o/ (IE *sekʷ- → Greek hep-)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 PIE *ḱ, *ǵ, *ǵʰ were originally reflected in Balkan languages as spirants /θ/ and /ð/, later in Albanian turning into /s/, /z/.

- 1 2 The Phrygian evidence is limited and often ambiguous so the issue of centum vs. satem reflexes is not completely settled, but the prevailing opinion is that Phrygian shows centum reflexes along with secondary palatalisation of /k/ to /ts/ and /ɡ/ to /dz/ before front vowels, as in most Romance languages, see Phrygian language#Phonology.

- 1 2 Proto-Germanic reflexes of Indo-European voiced stops had spirant allophones, retained in intervocalic position in Gothic.

- ↑ This is the reflex after nasals. The outcome in other positions is disputed and may vary according to phonetic environment. See the note in Grimm's law#In detail.

- ↑ Indic languages, ç represents a palatalized š sound

- 1 2 pIE *ǵʰ → proto-Indo-Iranian *džjh → Indic /h/, Iranian /z/.

- ↑ In Luvic languages, yielding ts, at least under most circumstances.

- 1 2 In Luvic languages, usually becoming *y initially, lost intervocalically.

- 1 2 In Luvic languages, yielding simple w.

In P-Celtic, Osco-Umbrian, and Aeolian Greek, *kw > /p/. That may be due to contact, perhaps in the Balkan region in the second millennium BC. The same /p/ also occurs in Hittite in a few pronominal forms (pippid 'something, someone', compare Latin quisquid).

See also

References

- 1 2 J.P. Mallory and D.Q. Adams (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture (1997), p. 461.

- ↑ Fortson 2010, chpt. 3.2–3.25

- ↑ Fortson 2010, p. 59, originally proposed in Melchert 1987

- ↑ Fortson 2010, p. 178

- 1 2 Fortson 2010, p. 59

- ↑ Lyovin 1997, p. 53

- ↑ Mallory 1997, p. 461.

- ↑ Quiles, C., López-Menchero, F., A Grammar of Modern Indo-European, Indo-European Association, 2012, p. 24.

- ↑ Holger Pedersen, KZ 36 (1900) 277–340; Norbert Jokl, in: Mélanges linguistiques offerts à M. Holger Pedersen (1937) 127–161.

- ↑ Vittore Pisani, Ricerche Linguistiche 1 (1950) 165ff.

- ↑ Schleicher 1871, p. 10

- ↑ Bynon, Theodora, "The Synthesis of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Studies: August Schleicher", in Auroux, Sylvain, History of the language sciences: an international handbook on, Volume 2, pp. 1223–1239

- ↑ Schleicher 1871, p. 163

- ↑ Brugmann 1886, p. 20

- ↑ Brugmann 1886, pp. 308–309

- ↑ Brugmann 1886, p. 312

- ↑ Brugmann 1886, p. 313. The quote given here is a translation by Joseph Wright, 1888.

- ↑ von Bradke 1890, p. 63

- ↑ von Bradke 1890, p. 107

- ↑ "Die Palatallaute der idg. Urzeit... erscheinen in Griech, Ital., Kelt., Germ. in der Regel als K-Laute, dagegen im Ar., Arm., Alb., Balt-Slav., denen sich Phrygisch und Thrakisch... meistens als Zischlaute." Brugmann & Delbrück 1897 p. 542.

- ↑ Brugmann & Delbrück 1897 p. 616. "...die Vertretung der qʷ-Laute... ist wie die der q-Laute,..."

- ↑ von Bradke 1890, p. 108

- ↑ K Shields, A New Look at the Centum/Satem Isogloss, Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung (1981).

- ↑ "...an early dialect split of the type indicated by the centum–satem contrast should be expected to be reflected in other high-order dialect distinctions as well, a pattern which is not evident from an analysis of shared features among eastern and western languages."Baldi, Philip (1999). The Foundations of Latin. Trends in Linguistics: Studies and Monographs 117. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co. p. 39. ISBN 978-3-11-016294-3.

- ↑ Kümmel, M.J. (2007), Konsonantenwandel. Bausteine zu einer Typologie des Lautwandels und ihre Konsequenzen für die vergleichende Rekonstruktion. Wiesbaden: Reichert. Cited in Prescott, C., Pharyngealization and the three dorsal stop series of Proto-Indo-European.

- ↑ Lehmann 1993, p. 100

- ↑ Such as Szemerényi (1995), Sihler (1995)

- ↑ Szemerényi 1990, p. 148

- ↑ R. Woodhouse, Indogermanische Forschungen (2010), 127–134.

- ↑ Some of these appear in: Quiles, C., López-Menchero, F., A Grammar of Modern Indo-European, Indo-European Association, 2012, p. 20ff.

- ↑ Craig Melchert (1987). "PIE velars in Luvian" (PDF). Studies in Memory of Warren Cowgill. pp. 182–204. Retrieved 2008-10-27.

- ↑ Craig Melchert (2013). "The Position of Anatolian" (PDF). Handbook of Indo-European Studies. pp. 18–22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-09. Retrieved 2010-06-29.

Sources

- Brugmann, Karl (1886). Grundriss der Vergleichenden Grammatik der indogermanischen Sprachen (in German). Erster Band. Strassburg: Karl J. Trübner.

- Brugmann, Karl; Delbrück, Berthold (1897–1916). Grundriss der vergleichenden grammatik der indogermanischen sprachen. Volume I Part 1 (2nd ed.). Strassburg: K.J. Trübner.

- Fortson, Benjamin W. (2010). Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. Blackwell Textbooks in Linguistics (2nd ed.). Chichester, U.K.; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Kortlandt, Frederik (1993). "General Linguistics & Indo-European Reconstruction" (PDF). Frederik Kortlandt. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- Lehmann, Winfred Philipp (1993). Theoretical Bases of Indo-European Linguistics. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Lyovin, Anatole (1997). An introduction to the languages of the world. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mallory, J.P.; Adams, D.Q., eds. (1997). "Proto-Indo-European". Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. London, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. ISBN 1-884964-98-2.

- Melchert, Craig (1987), "PIE velars in Luvian" (PDF), Studies in Memory of Warren Cowgill, pp. 182–204, retrieved 28 November 2009.

- Remys, Edmund (2007). "General distinguishing features of various Indo-European languages and their relationship to Lithuanian". Indogermanische Forschungen (IF). 112: 244–276.

- Schleicher, August (1871). Compendium der vergleichenden grammatik der indogermanischen sprachen (in German). Weimar: Hermann Böhlau.

- Solta, G.R. (1965). "Palatalisierung und Labialisierung". Indogermanische Forschungen (IF) (in German). 70: 276–315.

- Szemerényi, Oswald J. L. (1990). Introduction to Indo-European Linguistics. Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford University Press.

- von Bradke, Peter (1890). Über Methode und Ergebnisse der arischen (indogermanischen) Alterthumswissenshaft (in German). Giessen: J. Ricker'che Buchhandlung.

External links

- Anderson, Deborah. "Centum and satem Languages". EurAsia '98. Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- Baldia, Maximilian O. (2006). "Tombs and the Indo-European Homeland". The Comparative Archaeology Web. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- Wheeler, L. Kip. "The Indo-European Family of Languages". L. Kip Wheeler. Retrieved 5 December 2009.