Catholic Church in Albania

- The information in this article is from the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica and it is largely outdated. For current information, see de:Katholische Kirche in Albanien.

| Part of a series on |

| Albanians |

|---|

|

| States |

| Communities |

| Subgroups |

| People |

The Catholic Church in Albania is part of the worldwide Catholic Church, under the spiritual leadership of the Pope in Rome.

According to some sources around 16%-17% of the population of Albania were Catholic,[1][2] but in the 2011 census the percentage of Catholics was 10.03%.[3] (Although this may be an undercount due to emigration; the Albanian Orthodox Church,[4] the Greek minority, and the Bektashi community have all complained of being severely undercounted in the census.)[5] Catholicism is strongest in the northwestern part of the country, which historically had the most readily available contact with, and support from, Rome and the Republic of Venice. Shkoder is the center of Roman Catholicism in Albania. More than 20,000 Albanian Catholics are located in Montenegro, mostly in Ulcinj, Bar, Podgorica, Tuzi, Gusinje and Plav. This region is considered part of the Malsia Highlander region of the seven Albanian Catholic tribes. The region was split from Ottoman Albania after the First Balkan War.

There are five dioceses in the country, including two archdioceses plus an Apostolic Administration covering southern Albania.

History

For four centuries, the Albanian Catholics have defended their faith with the aid of:

- The Franciscan missionaries, especially since the middle of the 17th century, when persecutions by the Muslim lords set in motion the apostasy of many Albanian villages.

- The College of Propaganda at Rome, especially prominent in religious and moral support of Albanian Catholics. During the 17th and 18th centuries, particularly, it educated young clerics for service on the Albanian missions, contributing then as now to their support and to that of the churches.

- The Austrian Government, which gave about five thousand dollars yearly to the Albanian missions, in its role of Protector of the Christian community under Turkish rule. Apropos of the Austrian interest in Albania, it may be stated that it is the Austrian ambassador who obtains from the Sultan the Berat, or civil document of institution, for the Catholic bishops of Albania.[6]

The Church legislation of the Albanians was reformed by Pope Clement XI, effecting a general ecclesiastical visitation (1763) by the Archbishop of Antivari, at the close of which a national synod was held. Its decrees were printed by Propaganda (1705), and renewed in 1803.[7] In 1872, Pius IX caused a second national synod to be held at Scutari, for the renovation of the popular and ecclesiastical life.

Organization

The country is currently split into two Ecclesiastical provinces each headed by Archbishops - Shkodër-Pult in the north and Tiranë-Durrës in the centre and south. Shkodrë-Pult has two suffragan Diocese for Lezhë and Sapë. Tiranë-Durrës has one suffragan Diocese for Rrëshen as well as metropolitan authority over the Byzantine Rite Apostolic Administration of Southern Albania, also known as the Albanian Greek-Catholic Church.[8]

| Name | Area | Catholic Population | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Archdiocese of Shkodrë-Pult | Shkodër | 166,700 | 70% |

| Diocese of Lezhë | Lezhë | 86,300 | 71% |

| Diocese of Sapë | Zadrima, Vau-Dejes | 70,701 | 35% |

| Archdiocese of Tiranë-Durrës | Tirana | 135,400 | 11% |

| Diocese of Rrëshen | Rrëshen | 55,300 | 23% |

| Apostolic Administration of Southern Albania | Southern Albania | 3,000 | 0.2% |

The first known Bishop of present-day Albania was Bassus, who was made Bishop of Scutari (Shkodër) in 387, suffragan to the Bishop of Thessaloniki, Primate of all Illyricum. In the 6th century, Shkodër became a suffrage of Ohrid, in the present-day Republic of Macedonia, which was made the Primate of all Illyricum, and by the early Middle Ages, Shkodër was suffrage of the Bishop of Duklja, in present-day Montenegro. In 1867 Shkodër was united with the Archdiocese of Antivari (Bar, Montenegro), but split in 1886, to become a separate Archdiocese once again with suffragan bishops in Lezhë, Sapë and Pult. The Diocese of Pult (Pulati) - a region north of Shkodër between the present day villages of Drisht and Prekal - dates back to 899, when a Bishop of Pult was appointed as a suffragan to the Bishop of Duklja. The Diocese was once divided into Greater Pult and Lesser Pult but eventually merged with Shkodër in 2005. Drisht, a village north of Shkodër, also used to be a separate Bishopric. The Diocese of Sapë (Sappa) - covering the region of Zadrima between Shkodër and Lezhë - dates back to 1062, and that of Lezhë (Alessio) to the 14th century.[8] The Archdiocese of Durrës was created in the 13th century, as the Bishopric of Albanopolis. It united with Tirana in 1992. The Diocese of Rrëshen was split off in 1996.

The Apostolic Administration of Southern Albania was created in 1939.

Other former ancient Diocese in Albania were Dinnastrum and Balazum.[9][10]

The Mirdite tribe

The Mirdite tribe, the only tribe where the Albanian language and religion is still the same as centuries before. The oldest families (which are brothers in the same time) are: Oroshi, Kushneni and Spaqi. Fandi and Dibri family were hosted by the Mirdite (they came from southern Kosovo) later when those two tribe didn't want to obey the rules of the Ottoman Empire, thus the perfect place for this was Mirdite.

The Congress of Berlin and Albanian resistance

The revival of the national aspirations of Albania dates from the Congress of Berlin (1878), when Austria, in order to compensate Serbia and Montenegro for her retention of Bosnia and Herzegovina, thought to divide the land of Albania between them. The Turks secretly fostered the opposition of both Muslims and Catholics, and the Albanian League was formed "for the maintenance of the country's integrity and the reconstitution of its independence".

The territories allotted to Serbia were already occupied by her troops when resistance broke forth, and the idea of dislodging them had to be abandoned; but Montenegro was unable to obtain possession of her share, the rich districts of Gusinje and Plav. The Albanians, undaunted by the unexpected opposition of their former allies, the Turks, now forced by Russia to assist Montenegro, stood against all their enemies with a determination that baffled and dismayed Europe. Mehemet Ali was routed, his house at Đakovica burned down, and himself massacred.

The Albanians had much to avenge. They had not yet forgotten the war of a century before when their women flung themselves by hundreds over the roads near Yamina to escape Ali Pasha's soldiers. The Turks finally relinquished their efforts to quell the movement they had themselves helped to bring about, and Montenegro had to contend itself with the barren tracts of the Bojana and the port of Ulcinj. She could not have aspired even to these, had not Russia, favoring the cession of Albanian-inhabited lands to its client state Serbia, which shared with Russia common bonds of Orthodoxy and Slavic culture.

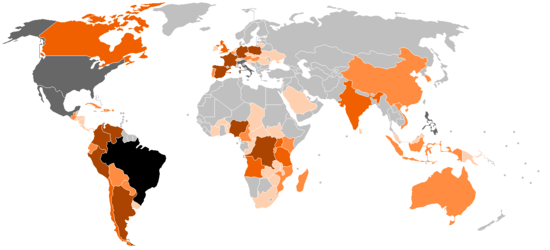

Demographics

According to the 2011 Albanian census, 10.03% of the population affiliated with Catholicism, while 56.7% were Muslims, 13.79% undeclared, 6.75% Orthodox believers, 5.49% other, 2.5% Atheists, 2.09% Bektashis and 0.14% other Christians.[3]

No clear statistics of any Turkish empire province has been assimilated. What is known though is that before the independence of Albania from Turkey, when the country had 1,500,000 inhabitants, the population's religious percentages were as these: 65% Muslim, 25% Albanian Orthodox Christian and 10% Roman Catholic. The CIA World Factbook uses the figures from the 1939 Census of 70% Muslim, 20% Eastern Orthodox Christian, and 10% Roman Catholic.[11]

Nonetheless, Catholic sources cite the statistics have changed significantly to this: 38.8% Muslim, 35.4% Christian (16.8% Roman Catholic, 16.1% Orthodox Christian, 0.6% Protestant, 0.6% Independent), 16.6% Non-religious (9.0% Atheist), 0.2% Baha'i.[1][2][12][13]

Gallery

See also

Sources

- William Martin Leake, Travels in Northern Greece (London, 1835)

- Élisée Reclus, The Earth and its Inhabitants (New York, 1895, Eng. tr.): Europe, I, 115-126

- Gustave Léon Niox, Péninsule des Balkans

- Edith Durham, Travels

- John Gardner Wilkinson, almatia and Montenegro (1848)

- Herder, Konvers. Lex., s. v.

- Ami Boué, la Turquie d'Europe (Paris, 1889)

- Alexandre Degrand, Souvenirs de la Haute-Albanie (Paris, 1901)

- Emanuele Portal, Note Albanesi (Palermo, 1903)

The documents of the medieval religious history of Albania are best found in the eight volumes of Daniele Farlati, Illyricum Sacrum (Venice, 1751–1819). See also Augustin Theiner, Vetera Monumenta Slavorum meridionalium historiam illustrantia (Rome, 1863 sqq.). Ecclesiastical statistics may be seen in O. Werner, Orbis Terrarum Catholicus (Freiburg, 1890), 122-124, and 120; also in the Missiones Catholicæ (Rome, Propaganda Press, triennially).

References

- 1 2 "Religious Freedom Page". Religiousfreedom.lib.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- 1 2 Archived 10 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Albanian census 2011

- ↑ "Official Declaration: The results of the 2011 Census regarding the Orthodox Christians in Albania are totally incorrect and unacceptable". orthodoxalbania.org. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ↑ "Final census findings lead to concerns over accuracy". Tirana Times. 19 December 2012. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Neber, in K. L., XI, 18, 19

- ↑ Coll. Lucensis Conc. Recent., I, 283 sq

- 1 2 Catholic Church in Albania, Catholic Hierarchy, accessed on 2008-06-14

- ↑ Archdiocese of Scutari, Catholic Encyclopedia via Shkoder.net, accessed on 2008-06-15

- ↑ Initiative for Making the Passage, Albanian History.net, accessed on 2008-06-15 Archived 1 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ 2009 CIA World Factbook

- ↑ Archived 7 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Atheist Statistics | Agnostic". Adherents.com. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "article name needed". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "article name needed". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.