Seville Cathedral

| Cathedral of Saint Mary of the See Catedral de Santa María de la Sede | |

|---|---|

|

View of the southeastern side of the Cathedral | |

| Basic information | |

| Location | Seville, Andalusia, Spain |

| Geographic coordinates | 37°23′9″N 5°59′35″W / 37.38583°N 5.99306°WCoordinates: 37°23′9″N 5°59′35″W / 37.38583°N 5.99306°W |

| Affiliation | Catholic |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Year consecrated | 1507 |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Metropolitan cathedral |

| Heritage designation | 1928, 1987 |

| Leadership | Archbishop Juan Asenjo Pelegrina |

| Website |

www |

| Architectural description | |

| Architect(s) | Alonso Martínez, Pedro Dancart, Carles Galtés de Ruan, Alonso Rodríguez |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Architectural style | Gothic |

| Groundbreaking | 1401 |

| Completed | 1528 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 135 metres (443 ft) |

| Width | 100 metres (330 ft) |

| Width (nave) | 15 metres (49 ft) |

| Height (max) | 42 metres (138 ft) |

| Spire(s) | 1 |

| Spire height | 105 metres (344 ft) |

| Official name: Cathedral, Alcázar and Archivo de Indias in Seville | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, vi |

| Designated | 1987 (11th session) |

| Reference no. | 383 |

| State Party |

|

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Official name: Catedral de Santa María de la Sede de Sevilla | |

| Type | Real property |

| Criteria | Monument |

| Designated | 29 December 1928 |

| Reference no. | (R.I.) - 51 - 0000329 - 00000 |

The Cathedral of Saint Mary of the See (Spanish: Catedral de Santa María de la Sede), better known as Seville Cathedral, is a Roman Catholic cathedral in Seville (Andalusia, Spain).[1] It is the largest Gothic cathedral and the third-largest church in the world. It is also the largest cathedral in the world, as the two larger churches, the Basilica of the National Shrine of Our Lady of Aparecida and St. Peter's Basilica, are not the seats of bishops. It was registered in 1987 by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, along with the Alcázar palace complex and the General Archive of the Indies.[2] "See" refers to the episcopal see, i.e., the bishop's ecclesiastical jurisdiction.

After its completion in the early 16th century, the Seville Cathedral supplanted Hagia Sophia as the largest cathedral in the world, a title the Byzantine church had held for nearly a thousand years. The cathedral is also the burial site of Christopher Columbus.[3] The Archbishop's Palace is located on the northeastern side of the cathedral.

Description

Seville Cathedral was built to demonstrate the city's wealth, as it had become a major trading center in the years after the Reconquista in 1248. In July 1401 it was decided to build a new cathedral. According to local oral tradition, the members of the cathedral chapter said: "Hagamos una Iglesia tan hermosa y tan grandiosa que los que la vieren labrada nos tengan por locos" ("Let us build a church so beautiful and so grand that those who see it finished will think we are mad").[4] Construction began in 1402 and continued until 1506. The clergy of the parish gave half their stipends to pay for architects, artists, stained glass artisans, masons, carvers, craftsman and labourers and other expenses.[5]

Five years after construction ended, in 1511, the dome collapsed and work on the cathedral recommenced. The dome again collapsed in 1888, and work was still being performed on the dome until at least 1903.[6] The 1888 collapse occurred due to an earthquake and resulted in the destruction of "every precious object below" the dome at that time.[7]

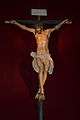

The interior has the longest nave of any cathedral in Spain. The central nave rises to a height of 42 meters and is lavishly decorated with a large quantity of gilding. In the main body of the cathedral, the most noticeable features are the great boxlike choir loft, which fills the central portion of the nave, and the vast Gothic retablo of carved scenes from the life of Christ. This altarpiece was the lifetime work of a single craftsman, Pierre Dancart.

The builders used some columns and other elements from the ancient mosque, including its minaret, which was converted into a bell tower known as La Giralda, now the city's most well-known symbol.

Giralda

The Giralda is the bell tower of the Cathedral of Seville. Its height is 343 feet (105 m), and its square base is 23 feet (7.0 m) above sea level and 44 feet (13 m) long per side. The Giralda is the former minaret of the mosque that stood on the site under Muslim rule, and was built to resemble the minaret of the Koutoubia Mosque in Marrakech, Morocco. It was converted into a bell tower for the cathedral after the Reconquista,[8] although the topmost section dates from the Renaissance. It was registered in 1987 as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. The tower is 104.5 m in height and was one of the most important symbols in the medieval city. Construction began in 1184 under the direction of architect Ben Ahmad Baso. According to the chronicler Ibn Sahib al-Salah, the works were completed on 10 March 1198, with the placement of four gilt bronze balls in the top section of the tower. After a strong earthquake in 1365, the spheres were missing. In the 16th century the belfry was added by the architect Hernán Ruiz the Younger; the statue on its top, called "El Giraldillo", was installed in 1568 to represent the triumph of the Christian faith.

Doors

Seville Cathedral has fifteen doors on its four facades. The major doors are:

West facade

The Door of Baptism, on the left side, was built in the 15th century and decorated with a scene depicting the baptism of Jesus, created by the workshop of Lorenzo Mercadante of Britain. It is of Gothic style with a pointed archivolt decorated with tracery. It contains sculptures of the brothers Saint Isidore and Saint Leander and the sisters Saints Justa and Rufina, by Lorenzo Mecadante, also a series of angels and prophets by the artisan Pedro Millán. The Main Door or Door of Assumption, in the center of the west facade, is well-preserved and elaborately decorated. Cardinal Cienfuegos y Jovellanos commissioned the artist Ricardo Bellver to carve the relief of the Assumption over the door; it was executed between 1877 and 1898.

The Door of Saint Michael or Door of the Nativity, has sculptures representing the birth of Jesus by Pedro Millan. It was built in the 15th century and is decorated with terracotta sculptures of Saint Laurean, Saint Hermengild and the Four Evangelists. Today, this door is used for the Holy Week processions.

South facade

The Door of Saint Cristopher or De la Lonja (1887–1895) of the south transept, was designed by Adolfo Fernandez Casanova and completed in 1917; it was originally designed by the architect Demetrio de los Rios in 1866. A replica of the "Giraldillo" stands in front of its gate.

North facade

The Door of the Conception (1895–1927), (Puerta de la Concepción) opens onto the Court of the Oranges (Patio de los Naranjos) and is kept closed except on festival days. It was designed by Demetrio de los Rios and finished by Adolfo Fernandez Casanova in 1895. It was built in the Gothic style to harmonize with the rest of the building.

The Door of the Lizard (Puerta del Lagarto) leads from the Court of the Oranges; it is named for the stuffed crocodile hanging from the ceiling.

The Door of the Sanctuary (Puerta del Sagrario) provides access to the sanctuary. Designed by Pedro Sanchez Falconete in the last third of the 17th century, it is framed by Corinthian columns with a sculpture on top representing King Ferdinand III of Castile next to the Saints Isidore, Leander, Justa and Rufina.

Door of Forgiveness. This door gives access to the Patio de los Naranjos from Calle Alemanes and therefore is not really a door of the cathedral. It belonged to the ancient mosque and retains its horseshoe arch shape from that time. In the early 16th century it was adorned with terracotta sculptures by the sculptor Miguel Perrin, highlighting the great relief of the Purification on the entrance arch. The plaster ornaments were made by Bartolomé López.

East facade

The Door of Sticks or the Adoration of the Magi, decorated with sculptures by Lope Marin in 1548, has a relief of the Adoration of the Magi at the top, executed by Miguel Perrin in 1520. The name "Palos" or "Sticks" is due to the wooden railing which separates that area from the rest of the building.

Door of the Bells, so named because at the time of its construction the bells to call the workers were rung there. The Renaissance sculptures and the relief on the tympanum representing Christ's Entry into Jerusalem were made by Lope Marin in 1548.

Door of the Baptism.

Door of the Baptism. Main Door or Door of Assumption.

Main Door or Door of Assumption. Door of Saint Miguel.

Door of Saint Miguel. Door of the Prince.

Door of the Prince. Door of Conception.

Door of Conception. Door of Palos.

Door of Palos. Detail of Door of Palos.

Detail of Door of Palos. Door of Forgiveness.

Door of Forgiveness.

Chapels

._Catedral_de_Sevilla.jpg)

The cathedral has 80 chapels, in which 500 masses were said daily as reported in 1896.[9] The baptistery Chapel of Saint Anthony contains the painting of The Vision of St. Anthony (1656) by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo. In November 1874, it was discovered that thieves had cut out the portion depicting Saint Anthony. Then in January 1875, a Spanish immigrant attempted to sell the same fragment to a New York City art gallery. The man stated it was a complete original by Murillo, Saint Anthony being one of the artist's favorite subjects. The owner of the gallery, Hermann Schaus, negotiated a price of $250 and contacted the Spanish consulate. Upon securing the sale, Schaus sent it to the Spanish Consulate, which shipped it to Seville via Havana and Cadiz.[10]

Timeline

- 1184 - Construction of the Almohad Mosque begun (Harvey 260)

- 1198 - Completion of the Mosque (Montiel 12) (Harvey 260)

- 1248 - Conquest of Seville by Ferdinand III, the mosque Christianized (Montiel 14)

- 1356 and 1362 - Two earthquakes destroy minaret, replaced by bell gable (Montiel 12)

- 1401 - (8 July- Harvey 230) Decision made to replace former mosque (Montiel 15)

- 1402 - Nave begun- SW corner (Harvey 260)

- 1432 - Nave completed, east end started (Harvey 260)

- 1466 - Demolition of Royal Chapel authorized by Juan II of Castile (Montiel 15)

- 1467 - East end completed, vaults begun. Anchors added. (Harvey 260)

- 1475 - Stalls begun (Harvey 260)

- 1478 - Stalls completed (Harvey 260)

- 1481 - Doorways in high altar completed (Montiel 16)

- 1482 - Retablo begun (ALTARPIECE) (Harvey 260)

- 1498 - Vaults completed, lantern begun (Harvey 260)*

- 1506 - Main dome (lantern) completed (Montiel 16) (Harvey 260)

- 1511 - Lantern collapses, rebuilding begins (Montiel 16) (Harvey 260)

- 1515 - New choir vaults completed (Montiel 16)*

- 1517 - New transept vaults completed (Montiel 16)*

- 1519 - Lantern rebuilding completed (Harvey 260)

- 1526 - Retablo Mayor completed (Harvey 260)

- 1551 - Capilla Real begun (Harvey 260)

- 1558 - Belfry replaces bell gable (Montiel 12)

- 1568 - Giralda, top stages (Harvey 260)

- 1575 - Capilla Real completed (Harvey 260)

- 1888 - Main dome and vaults collapse (Montiel 16)

- 1934 - Eduard Torres, priest and long-time choirmaster, dies

- 1995 - Infanta Elena of Spain, the elder daughter of King Juan Carlos and Queen Sofía, married Jaime de Maricharlar in the Cathedral.

Burials

- Christopher Columbus

- Ferdinand Columbus

- Fernando III of Castile

- Elisabeth of Hohenstaufen

- Alfonso X of Castile

- Pedro I of Castile

See also

- Giralda, the bell tower and former minaret

- 12 Treasures of Spain

Gallery

Seville Cathedral.

Seville Cathedral. Seville Cathedral.

Seville Cathedral. Exterior of the Cathedral (South view).

Exterior of the Cathedral (South view). View from inside of La Giralda.

View from inside of La Giralda. Façade of the Cathedral.

Façade of the Cathedral. Giralda as seen from the outside wall of the Patio de los Naranjos.

Giralda as seen from the outside wall of the Patio de los Naranjos. Giralda from Plaza Virgen de Los Reyes .

Giralda from Plaza Virgen de Los Reyes . Cathedral roofs as seen from the Giralda.

Cathedral roofs as seen from the Giralda. Interior of the Cathedral.

Interior of the Cathedral. Inside the Cathedral.

Inside the Cathedral. Inside the Cathedral.

Inside the Cathedral..jpg) Relics at the Cathedral.

Relics at the Cathedral.

Pierre Dancart's masterpiece, considered one of the finest altarpieces in the world.

Pierre Dancart's masterpiece, considered one of the finest altarpieces in the world.

Seville Cathedral Roof Collapse 1 August 1888 after earthquake

Seville Cathedral Roof Collapse 1 August 1888 after earthquake Panoramic view

Panoramic view Inside the cathedral

Inside the cathedral Details of vaults in front of main chapel

Details of vaults in front of main chapel

References

- ↑ "Seville Cathedral". spain.info. Spanish Tourism Board. Retrieved February 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "The other Europe: Cinque Terre, Bruges, Rothenburg, Edinburgh, Seville". Dallas Morning News. 31 May 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- ↑ "Cathedral, Alcázar and Archivo de Indias in Seville". UNESCO. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- ↑ Juan José Asenjo Pelegrina Archbishop of Seville (11 December 2012). "Una catedral para el siglo XXI". Archdiocese of Seville. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014.

Address by the Archbishop of Seville in the ceremony commemorating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the declaration of the monumental complex of the Cathedral, Alcázar and Archivo de Indias World Heritage Site by UNESCO

- ↑ Walter Matthew Gallichan; Catherine Gasquoine Hartley (1903). The Story of Seville. J.M. Dent & Company. p. 88.

- ↑ GallichanHartley 1903, p. 86

- ↑ Havelock Ellis (1915). The Soul of Spain. Houghton. p. 355.

- ↑ David Thomas; Alexander Mallett (3 August 2012). Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History. Volume 4 (1200-1350). BRILL. p. 9. ISBN 90-04-22854-3.

- ↑ Larkin Dunton (1896). The World and Its People. 5. Silver, Burdett. p. 289.

- ↑ "Art Theft History: 1874, Murillo's "Vision of St. Anthony"". Association for Research Into Crimes Against Art (ARCA). Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

Sources

- John Harvey, The Cathedrals of Spain

- Luis Martinez Montiel, The Cathedral of Seville

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Catedral de Sevilla. |

- Interactive 360° panorama from Plaza del Triunfo with Cathedral, Alcázar and Archivo General de Indias (Java, highres, 0,9 MB)

- Website with detailed information about Seville Cathedral

- Website showcasing sacred destinations including Seville Cathedral

- UNESCO list of World Heritage Monuments

- City Guide Website of Andalucia with information about Seville Cathedral

- Information on Seville_Cathedral

- Detials of Seville Cathedral as a national monument of Spain

- Travel Guide information regarding Seville Cathedral

- Great Building Website with details about Seville Cathedral

- Images pertaining to Seville Cathedral

- Bluffton University images and details pertaining to Catedral de Sevilla