Viking sword

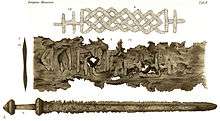

| Viking Age sword. | |

|---|---|

|

Two 10th-century sword hilts (Petersen type S) with Jelling style inlay decorations, with replicas, on display in Hedeby Viking Museum.[1] | |

| Type | Sword |

| Production history | |

| Produced | 8th to 11th centuries |

| Specifications | |

| Weight | ca. 1.0 to 1.5 kg[2] |

| Length | ca. 84 to 105 cm[2][3] |

| Blade length | ca. 70 to 90 cm[4] |

The Viking Age sword (also Viking sword) or Carolingian sword is the type of sword prevalent in Western and Northern Europe during the Early Middle Ages.

The Viking Age or Carolingian-era developed in the 8th century from the Merovingian sword (more specifically, the Frankish production of swords in the 6th to 7th century, itself derived from the Roman spatha) and during the 11th to 12th century in turn gave rise to the knightly sword of the Romanesque period.[5]

Terminology

Although popularly called "Viking sword", this type of sword was produced in the Frankish Empire during the Carolingian era. The association of the name "Viking" with these swords is due to the disappearance of grave goods in Christian Francia in the 8th century, due to which the bulk of sword blades of Frankish manufacture of this period were found in pagan burials of Viking Age Scandinavia, imported by trade, ransom payment or looting, while continental European finds are mostly limited to stray finds in riverbeds.[6]

Swords of the 8th to 10th centuries are also termed "Carolingian swords",[7] while swords of the late Viking Age and the beginning High Middle Ages (late 10th to early 12th centuries) blend into the category of Norman swords or the early development of the knightly sword.

History

During the reign of Charlemagne, the price of a sword (a spata, or longsword) with scabbard was set at seven solidi (Lex Ribuaria). Swords were still comparatively costly weapons, although not as exclusive as during the Merovingian period, and in Charlemagne's capitularies, only members of the cavalry, who could afford to own and maintain a warhorse, were required to be equipped with swords. Regino's Chronicle suggests that by the end of the 9th century, the sword was seen as the principal weapon of the cavalry.

The sword gradually replaced the sax during the late 8th to early 9th century. Because grave goods were no longer deposited in Francia in the 8th century, continental finds are mostly limited to stray finds in riverbeds (where anaerobic conditions favoured the preservation of the steel), and most extant examples of Carolingian swords are from graves from northern or eastern cultures where pagan burial customs were still in effect.

Pattern welding fell out of use in the 9th century, as higher quality steel became available. Better steel also allowed the production of narrower blades, and the swords of the 9th century have more pronounced tapering than their 8th-century predecessors, shifting the point of balance towards the hilt. Coupland (1990) proposes that this development may have accelerated the disappearance of the sax, as the sword was now available for swift striking, while the migration-period spatha was mostly used to deliver heavy blows aimed at damaging shields or armour. The improved morphology combined maneuverability and weight in a single weapon, rendering the sax redundant.[8]

The Frankish swords often had pommels shaped in a series of three or five rounded lobes. This was a native Frankish development which did not exist prior to the 8th century, and the design is frequently represented in the pictorial art of the period, e.g. in the Stuttgart Psalter, Utrecht Psalter, Lothar Gospels and Bern Psychomachia manuscripts, as well as in the wall frescoes in the church in Mals, South Tyrol. Likewise, the custom of inlaid inscriptions in the blades is Frankish innovation dating to the reign of Charlemagne, notably in the Ulfberht group of blades, but continued into the high medieval period and peaking in popularity in the 12th century. While blade inscriptions become more common over the Viking Age, the custom of hilt decorations in precious metals, inherited from the Merovingian sword and widespread during the 8th and 9th centuries, is in decline over the course of the 10th century. Most swords made in the later 10th century in what was now the Holy Roman Empire, while still conforming to the "Viking sword" type morphologically, have plain steel hilts.[9]

There are very few references to Carolingian-era sword production, apart from a reference to emundatores vel politores present in the workshops of the Abbey of Saint Gall.[10] Two men sharpening swords, one using a grindstone the other a file, are shown in the Utrecht Psalter (fol. 35v).

The distribution of Frankish blades throughout Scandinavia and as far east as Volga Bulgaria attest to the considerable importance of Frankish arms exports, even though Carolingian kings attempted to prevent the export of weapons to potential enemies; in 864, Charles the Bald set the death penalty on selling weapons to the Vikings.[11] Ibn Fadlan in the 10th century notes explicitly that the Volga Vikings carried Frankish swords.[12] The Saracens raiding Camargue in 869 demanded 150 swords as ransom for archbishop Rotland of Arles.

Carolingian scabbards were made of wood and leather. Scabbard decorations are depicted in several manuscripts (Stuttgart Psalter, Utrecht Psalter, Vivian Bible). A number of miniatures also show the system of suspension of the sword by means of the sword-belt. While the scabbards and belts themselves are almost never preserved, their metal mounts have been found in Scandinavian silver hoards and in Croatian graves.[13] A complete set seems to have included two to three oval or half-oval mounts, one large strap-end, a belt buckle and a trefoil mount. Their arrangement on the sword-belt has been reconstructed by Menghin (1973).[14]

Morphology

The seminal study of the topic is due to Jan Petersen (De Norske Vikingsverd, 1919).

Petersen introduced a morphological typology, mostly based on hilt shape. Petersen's types are identified by capital letters A–Z. Petersen listed a total of 110 specimens found in Norway. Of these, 40 were double-edged, 67 were single-edged and 3 indeterminate.

R. E. M. Wheeler in 1927 introduced a typology combining Petersen's hilt typology with a blade typology, in nine types labelled I to IX.

Geibig (1991) introduced an additional typology based on blade morphology (types 1–14) and a typology of pommel shapes (types 1–17, with subtypes), focussing on swords of the 8th to 12th centuries found within the boundaries of East Francia (as such including the transitional types between the "Viking" and the "knightly" sword).

Wheeler typology

- type I: hilt types F, G, M, P, Q, Æ; mid 9th to early 11th centuries; light pommels without lobes

- type II: hilt types A, B, C, H, I. Norwegian, mid 9th to mid 10th centuries (Norwegian?); heavy, triangular pommels of the type inherited from the Merovingian sword.

- type III: hilt types D, E, R, S, T, U, V, early 9th to mid 10th centuries (Danish?); various forms of three-lobed pommels.

- type IV: hilt types K, O, late 8th to mid 10th centuries (Frankish?); pommels with five or seven lobes.

- type V, hilt type L, mid 9th to late 10th centuries (English); rare "Wallingford Type" pommel, likely a native Anglo-Saxon development.

- type VI, hilt type L, early 10th to mid 11th centuries (Danish); a derived design with three lobes, likely of Danish origin.

- type VII: hilt types N, W, X; mid 9th to late 11th centuries; the semi-circular pommel shape typical of the Ottonian period and continued as the "mushroom" pommel in high medieval swords.

- types VIII and IX, 10th to 13th centuries, development of the high medieval "brazil-nut" or "tea-cosy" pommel types.

The Oakeshott typology is a continuation of Wheeler's typology to include high medieval swords.

Artilength, fuller length, blade width and degree of taper.[16]

- Type 1 of the late migration period and early Viking Age (8th century) has blade lengths of 70 to 80 cm, with a taper to about 80% of maximum width over 60 cm. The fuller is shallow or absent entirely; these blades are mostly pattern welded, with four or five bands visible on each blade face.

- Type 2 spans the mid 8th to mid 10th centuries. Slightly longer than type 1, at 74 to 83 cm, the defining characteristic is the more pronounced taper.

- Type 3 is contemporary with type 2, and of similar length (74 to 85 cm) but has wider blades (52 to 57 mm at the hilt).

- Type 4 dates to the later Viking Age (mid 10th to mid 11th centuries). They represent a trend towards shorter blades at

the time, at 63 to 76 cm.

- Type 5 originates in the mid 10th century, and is transitional to the knightly sword of the 11th to 12th centuries. The longest blades of the Viking Age fall into this type, at lengths of 84 to 91 cm. These blades also introduce the 12th-century fashion of sword blade inscriptions of the ME FECIT and IN NOMINE DOMINI type.

Metallurgy

An important aspect in the development of the European sword between the early and high medieval periods is the availability of high-quality steel. Migration period as well as early medieval sword blades were primarily produced by the technique of pattern welding, also known as "false Damascus" steel. Blooms of high-quality steel large enough to produce an entire sword blade were only rarely available in Europe at the time, mostly via import from Central Asia, where a crucible steel industry began to establish itself from c. the 8th century. Higher quality swords made after AD 1000 are increasingly likely to have crucible steel blades. The group of Ulfberht swords includes a wide spectrum of steel and production method. One example from a 10th-century grave in Nemilany, Moravia, has a pattern-welded core with welded-on hardened cutting edges. Another example appears to have been made from high-quality hypoeutectoid steel possibly imported from Central Asia.[17]

Notable examples

- The Sæbø sword, a 9th-century type C sword found in 1825 in a barrow at Sæbø, Vikøyri, in Norway's Sogn region. The sword is notable for its blade inscription, which has been interpreted as runic by George Stephens (1867), which would be very exceptional; while Viking Age sword hilts were sometimes incised with runes, inlaid blade inscriptions are, with this possible exception, invariably in the Latin alphabet.

- One of the heaviest and longest extant swords of the Viking Age is dated to the 9th century and was found in Flå, now kept at Museum of Cultural History, Oslo, at a total length of 102.4 cm and a mass of 1.9 kg.[2]

- Sword of Saint Stephen: A 10th-century sword of Petersen type T with a walrus-tooth hilt with carved Mammen style ornaments. On display as the coronation sword of Hungarian king Saint Stephen in the Treasury of St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague.[18]

- Lincoln sword (River Witham sword): A sword dated to the 10th century, with a blade of German/Ottonian manufacture classified as a Petersen type L variant (Evison's "Wallingford Bridge" type) and hilt fittings added by an Anglo-Saxon craftsman, was recovered from the River Witham opposite Monks Abbey, Lincoln in 1848.[19] Peirce (1990) makes special mention of this sword as "breath-taking", "one of the most splendid Viking swords extant".[20] The Lincoln sword is also remarkable for being one of only two known bearing the blade inscription Leutfrit (+ LEUTFRIT), the other being a find from Tatarstan (at the time Volga Bulgaria, now kept in the Historical Museum of Kazan). On the reverse side, the blade is inlaid with a double scroll pattern.[21]

- The Sword of Essen is a 10th-century sword preserved at Essen Abbey, decorated with gold plating at the close of the 10th century.

- The Cawood sword, and the closely related Korsoygaden sword, are notable in the context of delineating "Viking Age swords" from derived high medieval types; these swords fit neatly into the "Viking sword" typology, but Oakeshott (1991) considers them derived types dating to the 12th century.[22]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Viking swords. |

References

- ↑ M. Müller-Wille, "Zwei wikingerzeitliche Prachtschwerter aus der Umgebung von Haithabu", Offa 29 (1972) 50-112 (cited after Schulze-Dörrlamm (2012:625).

- 1 2 3 Universitetets Oldsaksamling, Oslo C777 length: 102.4cm, blade length: 86 cm, weight 1.9 kg. Peirce (2002:36): "it is extremely rare to find a Viking Age sword with an overall length of more than 1 metre. Even considering the huge pommel, this weapon has a very poor balance and consequently does not handle easily. [...] Petersen determined the weight of C777 as a massive 1.896 kg (4.17 lb)."

- ↑ Ingelrii sword found in the Thames: length 84.2 cm (blade 69.7 cm): Peirce (2002:80). There are shorter swords found in boys' graves, presumably shortened from full sized sword (Peirce 2002:86) and in some cases diminutive swords made for boys (Peirce 2002:95).

- ↑ L. A. Jones in Peirce (2002:23), citing Geibig (1991): "Dimensions of Viking Age Sword Blades in Geibig's Classification" type 1: 70–80 cm, type 2: 74–83 cm, type 3: 74–85 cm, type 4: 63–76 cm, type 5: 84–91 cm.

- ↑ Oakeshott, R.E. (1996). The Archaeology of Weapons, Arms and Armour from Prehistory to the Age of Chivalry. New York: Dover Publications Inc. ISBN 978-0-486-29288-5.

- ↑ V. D. Hampton,"Viking Age Arms and Armor Originating in the Frankish Kingdom", The Hilltop Review 4.2 (2011), 36–44.

- ↑ Goran Bilogrivić, Carolingian Swords from Croatia – New Thoughts on an Old Topic, Studia Universitatis Cibiniensis X (2013). Madeleine Durand-Charre, "Merovingian and Carolingian swords", Microstructure of Steels and Cast Irons, Engineering Materials and Processes, Springer Science & Business Media (2013), 16ff.

- ↑ Simon Coupland, "Carolingian Arms and Armor in the Ninth Century", Viator: Medieval and Renaissance Studies 21 (1990).

- ↑ Schulze-Dörrlamm (2012:623): "In den Waffenschmieden des Reiches sind während des 10. Jahrhunderts offenbar nur sehr schlichte, unverzierte Eisenschwerter (Typ X) 84 mit einteiligem, halbkreisförmigem Knauf und gerader Parierstange, wenngleich mit gut geschmiedeter, damaszierter Klinge hergestellt worden, wie z. B. das Schwert aus dem Lek bei Dorestad (prov. Utrecht / NL). Deshalb mögen den Kaisern der damaligen Zeit typische »Wikingerschwerter« mit ihren prächtig ausgestalteten, wuchtigen Griffen für Repräsentationszwecke besser geeignet erschienen sein."

- ↑ W. Horn and E. Born, The Plan of St. Gall, 3 vols. (Berkeley 1979) 2.190.

- ↑ Capitulare missorum in Theodonis villa datum secundum, generale c. 7; Capitulare Bononiense 10, 167; both decrees were included by Ansegisus in his collection of laws, as articles 3.6 and 3.75 respectively; Edictum Pistense c. 25.

- ↑ cited after J. Brondsted, The Vikings, ed. 2 (Harmondsworth 1965) 265.

- ↑ E. Wamers, "Ein karolingischer Prunkbeschlag aus dem Römisch‑Germanischen Museum, Kö1n," Zeitschrift fur Archäologie des Mittelalters 9 (1981) 91-128.

- ↑ W. Menghin, "Aufhängevorrichtung and Trageweise zweischneidiger Langschwerter aus germanischen Gräbern des 5. bis 7. Jahrhunderts," Anzeiger des Germanischen Nationalmuseums (1973).

- ↑ Notes sur la collection d'armes anciennes du Major Henry Galopin, Geneva (1913), plate 8, no. 1: Epée carolingienne du Xe siècle, pommeau à 3 lobes avec inscription en caractères runiques, fusée manque, provenance: Trèves.

- ↑ Geibig (1991); Peirce (2002), 21–24.

- ↑ David Edge, Alan Williams: Some early medieval swords in the Wallace Collection and elsewhere, Gladius XXIII, 2003, 191-210 (p. 203).

- ↑ Schulze-Dörrlamm (2012:630)

- ↑ British Museum 1848,10-21,1 Antiquities from the River Witham, Archaeology Series No. 13, Lincolnshire Museums Information Sheet (1979)

- ↑ Peirce, Ian (1990), "The Development of the Medieval Sword c.850–1300", in Christopher Harper-Bill, Ruth Harvey (eds.), The Ideals and Practice of Medieval Knighthood III: Papers from the Fourth Strawberry Hill Conference, 1988, Boydell & Brewer Ltd, pp. 139–158 (p. 144).

- ↑ British Museum 1848,1021.1. Kendrick, T. D. (1934): 'Some types of ornamentation on Late Saxon and Viking Period Weapons in England', Eurasia Septentrionalis Antiqua, ix, 396 and fig. 2; Maryon, Herbert. (1950): 'A Sword of the Viking Period from the River Witham', The Antiquaries Journal, xxx, 175-79; '

- ↑ "the runes inscribed upon the bronze collars which once held the grip at top and bottom [...] rather roughly incised in a rather 'home-made' style, have been positively dated as being no later than 1150 and unlikely to be much earlier than 1100. These datings have been made by two extremely eminent Runologists, Eric Moltke and O. Rygh, each independently corrobating the other's finding. On stylistic grounds and on the circumstances of its burial, Jan Petersen dated the sword to c. 1050" Oakeshott (1991:76)

- Alfred Geibig, Beiträge zur morphologischen Entwicklung des Schwertes im Mittelalter (1991).

- P. Paulsen, Schwertortbänder der Wikingerzeit (1953).

- Ian G. Peirce, Swords of the Viking Age, 2002.

- Jan Petersen, De Norske Vikingsverd, 1919 (archive.org).

- Mechthild Schulze-Dörrlamm, "Schwerter des 10. Jahrhunderts als Herrschaftszeichen der Ottonen", Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums 59 (2012) 609–651

External links

- Swords (vikingage.org)

- Wiglaf's Weapon Widget Database of Viking swords.

- The Norwegian Viking Swords by Jan Petersen, translated by Kristin Noer An online English translation of Jan Petersen's typology of Viking swords.

- Christopher L. Miller, The Sword Typology of Alfred Geibig (myarmoury.com)