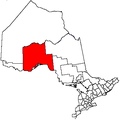

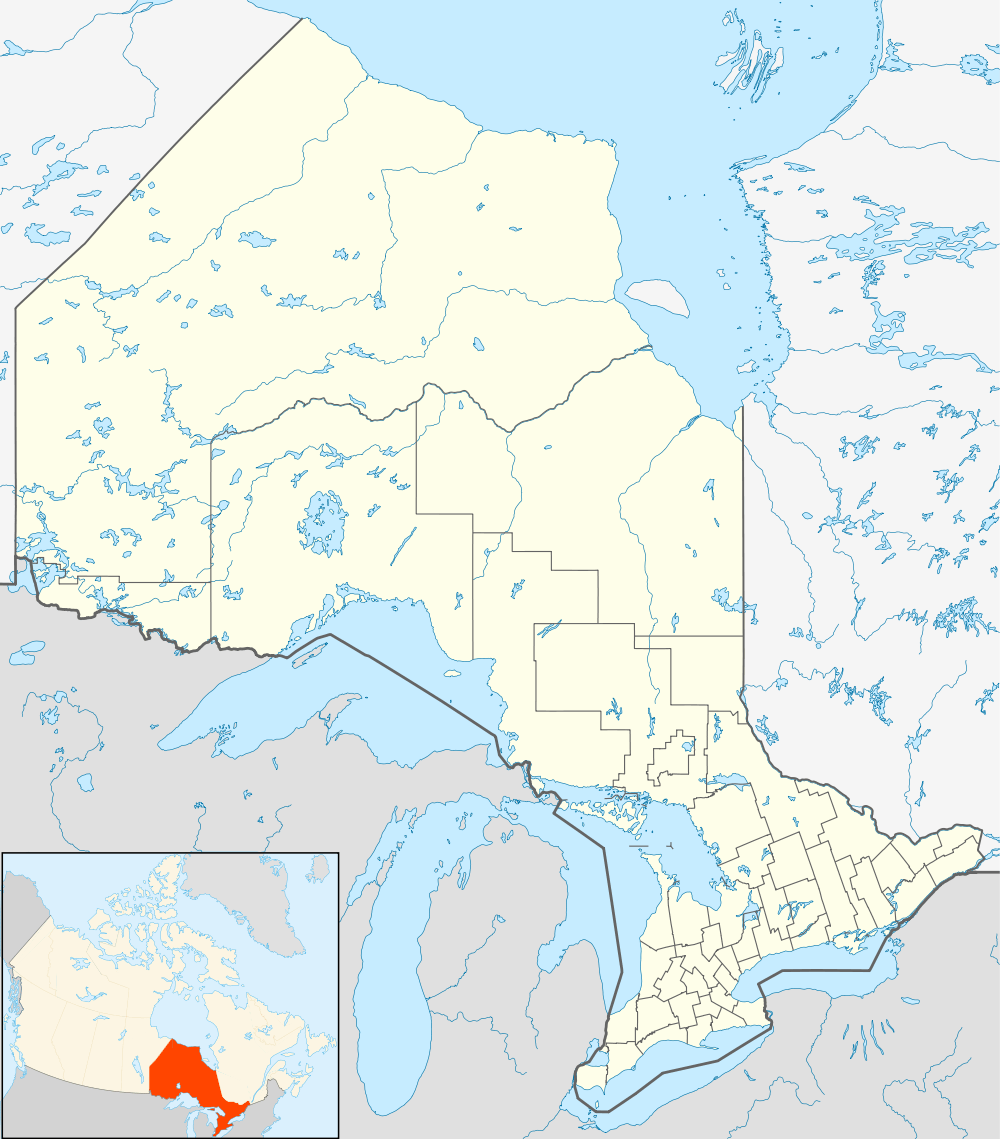

Greenstone, Ontario

| Greenstone | ||

|---|---|---|

| Municipality (single-tier) | ||

| Municipality of Greenstone Municipalité de Greenstone | ||

|

Municipal office of Greenstone in Geraldton | ||

| ||

| Motto: "Spirit of the North" | ||

|

| ||

Greenstone | ||

| Coordinates: 50°00′N 86°44′W / 50.000°N 86.733°WCoordinates: 50°00′N 86°44′W / 50.000°N 86.733°W | ||

| Country |

| |

| Province |

| |

| District | Thunder Bay | |

| Formed | 2001 | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Renald Beaulieu | |

| • Federal riding | Thunder Bay—Superior North | |

| • Prov. riding | Thunder Bay—Superior North | |

| Area[1] | ||

| • Land | 2,767.76 km2 (1,068.64 sq mi) | |

| Elevation[2] | 348.40 m (1,143.04 ft) | |

| Population (2011)[1] | ||

| • Total | 4,724 | |

| • Density | 1.7/km2 (4/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | EST (UTC-5) | |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) | |

| Postal code FSA | P0T | |

| Area code(s) | 807 | |

| Website | www.greenstone.ca | |

Greenstone is an amalgamated town in the Canadian province of Ontario with a population of 4724 according to the 2011 Canadian census. It stretches along Highway 11 from Lake Nipigon to Longlac and covers 2,767.76 square kilometres (1,068.64 sq mi).

The town was formed in 2001, as part of a wave of community amalgamations under the Progressive Conservative government of Ontario.[3] It combined the former Townships of Beardmore and Nakina, the Towns of Geraldton and Longlac with large unincorporated portions of Unorganized Thunder Bay District.

It is the administrative office of the Animbiigoo Zaagi'igan Anishinaabek First Nation band government.[4]

Communities

Greenstone includes the communities of Beardmore, Caramat, Geraldton, Jellicoe, Longlac, Macdiarmid, Nakina and Orient Bay. Nakina and Caramat are entirely exclaved from the rest of the municipality's territory.

-

Geraldton

-

Beardmore

-

Longlac

-

Nakina

History

T.L. Taunton, Geological Survey of Canada, noted gold in quartz fragments around Little Long Lac in 1917. Similarly, Tony Oklend found ore in a boulder during World War I. However, it wouldn't be until 1931 that Bill "Hard Rock" Smith and Stan Watson would stake 18 claims along 3 veins. Tom Johnson and Robert Wells filed claims based on gold appearing in Magnet Lake quartz outcrop and the presence of bismuthinite. The Bankfield Gold Mine developed from these claims. In 1932, Johnson and Oklend staked 12 claims at Little Long Lac. Fred MacLeod and Arthur Cockshutt filed 15 claims near Smith's.[5]

Nakina was first established in 1923 as a station and railway yard on the National Transcontinental Railway, between the divisional points of Grant and Armstrong. Nakina was at Mile 15.9 of the NTR's Grant Sub-Division. Following the completion in 1924 of Canadian National Railways's Longlac-Nakina Cut-Off, connecting the rails of the Canadian Northern at Longlac and the NTR, Nakina became the new divisional point, and the buildings from the town of Grant (25 kilometers to the east) were moved to the new Nakina town site.

By 1934, a gold rush absorbed the area from Long Lac to Nipigon, a belt 100 km long and 40 km wide. The village of Hard Rock was established in 1934, and Longlac, Bankfield, and Geraldton soon followed. Though a 1936 fire was threatened the mines, development was able to continue.[5]

As an important railway service stop from 1923 until 1986, the town had a railway round-house as well as a watering and fueling capability. During World War II, there was also a radar base[6] on the edge of the town, intended to watch for a potential attack on the strategically important Soo Locks at Sault Ste. Marie. Research into the radar site in the National Archives of Canada indicates that it was largely a United States Army Air Forces operation, pre-dating the Pinetree Line radar bases that were erected to focus on the Cold War threat. The Nakina base was totally removed shortly after the war.

The settlement of Geraldton is a compound of the surname of financiers of a nearby gold mine near Kenogamisis Lake in 1931 (Fitzgerald and Errington).[7]

The Geraldton-Beardmore Gold Camp, in the heart of the Canadian Shield, hosts numerous mineralized zones which continue to be explored for potential development. Eight gold mines operated here between 1936 and 1970.

Tom Powers and Phil Silams staked what became the Northern Empire Mine (1925-1988) near Beardmore, which produced a total of 149,493 ounces of gold. The Little Long Lac Mine (1934-1953) produced 605,449 ounces of gold, besides producing scheelite. J.M. Wood and W.T. Brown developed the Sturgeon River Gold Mine (1936-1942), which produced 73,438 ounces of gold. James and Russell Cryderman found and Karl Springer incorporated what became known as the Leitch Gold Mine (1936-1968), which produced 861,982 ounces of gold from 0.92 grade ore. The Bankfield Gold Mines produced 66,416 ounces by 1942. Tomball Mines (1938-1942), started by Tom and Bill Johnson, produced 69,416 ounces. The Magnet Mine (1938-1942) produced 152,089 ounces. The Hard Rock Mine (1938-1951) produced 269,081 ounces, while the MacLeod-Cockshutt (1938-1970) produced 1,516,980 ounces.[5]

In the 1970s pulp and paper operations near the town resulted in growth in the towns population to its peak of approximately 1200. However, at this point cost controls in the railway industry meant that service and maintenance could be consolidated at points much more distant from one another than had been common in the first half of the 20th century. As a result, the value of Nakina as a railway service community was greatly diminished, to the point where it was no longer a substantial employer in the town. Also in the 1970s, a radio station was launched in Longlac as CHAP on the AM dial, which left the air by the late 70s.[8]

As of 2004 the town remains focused on tourism, diminished pulp and paper operations and support of other more northern communities (food, fuel and transportation). Mining and minerals industries are often seen as a source of further growth, though the Canadian Shield geology of the area makes extraction of minerals like gold an expensive operation.

As of 2009, a proposed ore transport point around Nakina, as part of the Ring of Fire development, may shift the emphasis of local industry from logging back to mining. In 2010 the Ring of Fire development, proposed James Bay rail link and placement of processing plants remains of great economic interest for the region. Development is slated to move over the next three to five years in an over 1.5 billion dollar project.

On 19 February 2011, Beardmore was temporarily evacuated after a major explosion ruptured the Trans-Canada Pipeline in the community.[9]

Demographics

| Canada census – Greenstone, Ontario community profile | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2006 | 2001 | |

| Population: | 4724 (-3.3% from 2006) | 4906 (-16.9% from 2001) | 5907 (-13.3% from 1996) |

| Land area: | 2,767.76 km2 (1,068.64 sq mi) | 2,780.99 km2 (1,073.75 sq mi) | 2,780.56 km2 (1,073.58 sq mi) |

| Population density: | 1.7/km2 (4.4/sq mi) | 1.8/km2 (4.7/sq mi) | 2.0/km2 (5.2/sq mi) |

| Median age: | 39.8 (M: 40.2, F: 39.5) | 36.8 (M: 36.8, F: 36.8) | |

| Total private dwellings: | 2629 | 2596 | 2702 |

| Median household income: | $64,153 | $52,972 | |

| Notes: Includes population and dwelling count amendments.[10] – References: 2011[1] 2006[11] 2001[12] | |||

- Population in 2006: 4906 (or 4886 when adjusted to 2011 boundaries)

- Population in 2001: 5907

- Population total in 1996: 6530

- Beardmore (township): 418

- Geraldton (town): 2627

- Longlac (town): 2074

- Nakina (township): 566

- Population in 1991:

- Beardmore (township): 454

- Geraldton (town): 2633

- Longlac (town): 2073

- Nakina (township): 635

Government

Greenstone's mayor is Renald Beaulieu.

The Greenstone Public Library has branches in Beardmore, Geraldton (the Elsie Dugard Centennial Branch), Longlac and Nakina (the Helen Mackie Memorial Branch).

Climate

Greenstone experiences a humid continental climate (Dfb), with long, brutally cold winters and warm summers. The highest temperature ever recorded was 40.0 °C (104 °F) on July 11 & 12, 1936 (at Longlac).[14] The coldest temperature ever recorded was −50.2 °C (−58.4 °F) on 31 January 1996 (at Geraldton Airport).[2]

| Climate data for Greenstone (Geraldton Airport), 1981−2010 normals, extremes 1921−present[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 7.8 (46) |

11.1 (52) |

20.7 (69.3) |

28.9 (84) |

33.1 (91.6) |

37.0 (98.6) |

40.0 (104) |

36.7 (98.1) |

32.8 (91) |

28.9 (84) |

20.1 (68.2) |

10.8 (51.4) |

40.0 (104) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −12.1 (10.2) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

7.4 (45.3) |

15.4 (59.7) |

21.0 (69.8) |

23.5 (74.3) |

22.3 (72.1) |

16.0 (60.8) |

7.6 (45.7) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−8.9 (16) |

6.8 (44.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −18.6 (−1.5) |

−15.8 (3.6) |

−8.9 (16) |

0.6 (33.1) |

8.5 (47.3) |

14.3 (57.7) |

17.2 (63) |

16.0 (60.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−14.2 (6.4) |

0.6 (33.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −25.1 (−13.2) |

−23.1 (−9.6) |

−16.4 (2.5) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

1.5 (34.7) |

7.6 (45.7) |

10.7 (51.3) |

9.7 (49.5) |

4.9 (40.8) |

−1.1 (30) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

−19.5 (−3.1) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −50.2 (−58.4) |

−49.3 (−56.7) |

−45.0 (−49) |

−36.1 (−33) |

−15.0 (5) |

−6.1 (21) |

−3.9 (25) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−24.4 (−11.9) |

−37.8 (−36) |

−46.7 (−52.1) |

−50.2 (−58.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 33.5 (1.319) |

23.8 (0.937) |

31.9 (1.256) |

45.7 (1.799) |

71.7 (2.823) |

84.5 (3.327) |

108.6 (4.276) |

83.6 (3.291) |

101.6 (4) |

83.1 (3.272) |

58.7 (2.311) |

38.0 (1.496) |

764.6 (30.102) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.4 (0.016) |

0.6 (0.024) |

7.2 (0.283) |

22.1 (0.87) |

66.1 (2.602) |

84.5 (3.327) |

108.6 (4.276) |

83.6 (3.291) |

99.5 (3.917) |

62.3 (2.453) |

17.5 (0.689) |

3.7 (0.146) |

556.1 (21.894) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 42.8 (16.85) |

29.4 (11.57) |

28.4 (11.18) |

24.0 (9.45) |

4.6 (1.81) |

Trace | 0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

2.0 (0.79) |

19.6 (7.72) |

46.8 (18.43) |

45.0 (17.72) |

242.6 (95.51) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 14.0 | 11.3 | 11.7 | 9.8 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 14.7 | 14.0 | 15.8 | 16.4 | 15.9 | 16.5 | 167.0 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.48 | 0.59 | 2.1 | 5.0 | 12.2 | 14.0 | 14.7 | 14.0 | 15.5 | 11.8 | 4.3 | 1.2 | 95.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 14.9 | 11.6 | 10.2 | 6.3 | 2.1 | 0.07 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.80 | 6.8 | 13.9 | 17.1 | 83.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 68.1 | 61.1 | 53.7 | 48.0 | 49.2 | 52.7 | 55.5 | 56.6 | 63.3 | 68.7 | 75.0 | 74.5 | 60.5 |

| Source: Environment Canada[2][15][16][17][18][19] | |||||||||||||

In film

The CBC first nations television series Spirit Bay was shot here in the mid-1980s at the Biinjitiwabik Zaaging Anishnabek First Nations Reserve.

Notable people

- Curtis Bois (born 1974), professional ice hockey player

See also

- Beardmore Relics, Viking Age artifacts 'found' near Beardmore, Ontario; originally proposed to be evidence of Vikings in Ontario. Later, the relics were proven to have been a hoax. Through a series of witnesses as well as the son of the person who had originally found them, the relics were found to have been 'planted' in Beardmore and not, as was suggested, 'found' there.

- List of townships in Ontario

- List of francophone communities in Ontario

- Matachewan, Ontario

- Cobalt silver rush

- Porcupine Gold Rush

- Red Lake, Ontario

- Hemlo, Ontario

References

- 1 2 3 "Greenstone census profile". 2011 Census of Population. Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2012-03-29.

- 1 2 3 "Geraldton A, Ontario". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved February 17, 2015.

- ↑ Municipal Act RSO 1990 c.M.45

- ↑ http://www.aza.ca

- 1 2 3 Barnes, Michael (1995). Gold in Ontario. Erin: The Boston Mills Press. pp. 78–83. ISBN 155046146X.

- ↑ Dziuban, Stanley W. (1970). Military Relations Between the United States and Canada 1939 - 1945. United States Army Center of Military History. p. 196. CMH Pub 11-5. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ↑ http://www.ruralroutes.com/5939.html

- ↑ CHAP AM (1970-1977) - Canadian Communications Foundation.

- ↑ "Pipeline blast forces evacuation of northern Ontario town". Toronto Star, 20 February 2011.

- 1 2 "Population and dwelling count amendments". 2001 Census data. Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- ↑ "2006 Community Profiles". Canada 2006 Census. Statistics Canada. March 30, 2011. Retrieved 2012-03-29.

- ↑ "2001 Community Profiles". Canada 2001 Census. Statistics Canada. February 17, 2012. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- ↑ Statistics Canada: 1996, 2001, 2006 census

- ↑ "Daily Data Report for July 1936". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ↑ "Geraldton A, Ontario". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved February 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Longlac". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ↑ "Geraldton Forestry". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ↑ "Geraldton". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ↑ "Geraldton A". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ↑ Extreme high and low temperatures in the table below were recorded at Longlac from March 1921 to July 1948, at Geraldton from August 1948 to July 1981 and at Geraldton Airport from August 1981 to present.

External links

|

Unorganized Thunder Bay |  | ||

| Lake Nipigon / Rocky Bay 1 | |

Unorganized Thunder Bay | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Unorganized Thunder Bay, Ginoogaming First Nation |

|

Unorganized Thunder Bay |  | ||

| Unorganized Thunder Bay | |

Unorganized North Cochrane | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Unorganized Thunder Bay |

|

Unorganized Thunder Bay |  | ||

| Unorganized Thunder Bay | |

Unorganized Thunder Bay | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Unorganized Thunder Bay |