Callitrichidae

| Callitrichidae[1][2] | |

|---|---|

| |

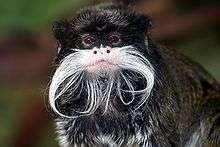

| Major extant callitrichid genera: Callithrix, Leontopithecus, Saguinus, Cebuella, Mico, Callimico. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorrhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Parvorder: | Platyrrhini |

| Family: | Callitrichidae Gray, 1821 |

| Type genus | |

| Callithrix | |

| Genera | |

|

Cebuella | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Callitrichidae (also called Arctopitheci or Hapalidae) are a family of New World monkeys, including marmosets and tamarins. At times, this group of animals has been regarded as a subfamily, called Callitrichinae, of the family Cebidae.

This taxon was traditionally thought to be a primitive lineage, from which all the larger-bodied platyrrhines evolved.[3] However, some works argue that callitrichids are actually a dwarfed lineage.[4][5]

Ancestral stem-callitrichids likely were "normal-sized" ceboids that were dwarfed through evolutionary time. This may exemplify a rare example of insular dwarfing in a mainland context, with the "islands" being formed by biogeographic barriers during arid climatic periods when forest distribution became patchy, and/or by the extensive river networks in the Amazon Basin.[4]

All callitrichids are arboreal. They are the smallest of the simian primates. They eat insects, fruit, and the sap or gum from trees; occasionally they take small vertebrates. The marmosets rely quite heavily on tree exudates, with some species (e.g. Callithrix jacchus and Cebuella pygmaea) considered obligate exudativores.[6]

Callitrichids typically live in small, territorial groups of about five or six animals. Their social organization is unique among primates and is called a "cooperative polyandrous group". This communal breeding system involves groups of multiple males and females, but only one female is reproductively active. Females mate with more than one male and each shares the responsibility of carrying the offspring.[7]

They are the only primate group that regularly produces twins, which constitute over 80% of births in species that have been studied. Unlike other male primates, male callitrichids generally provide as much parental care as females. Parental duties may include carrying, protecting, feeding, comforting, and even engaging in play behavior with offspring. In some cases, such as in the cotton-top tamarin (Saguinus oedipus), males, particularly those that are paternal, will even show a greater involvement in caregiving than females.[8] The typical social structure seems to constitute a breeding group, with several of their previous offspring living in the group and providing significant help in rearing the young.

Species list

- Family Callitrichidae

- Genus Cebuella

- Pygmy marmoset, Cebuella pygmaea

- Genus Callibella

- Roosmalens' dwarf marmoset, Callibella humilis

- Genus Mico

- Silvery marmoset, Mico argentatus

- White marmoset, Mico leucippe

- Black-tailed marmoset, Mico melanurus

- Hershkovitz's marmoset, Mico intermedius

- Emilia's marmoset, Mico emiliae

- Black-headed marmoset, Mico nigriceps

- Marca's marmoset, Mico marcai

- Santarem marmoset, Mico humeralifer

- Gold-and-white marmoset, Mico chrysoleucus

- Maués marmoset, Mico mauesi

- Satéré marmoset, Mico saterei

- Manicoré marmoset, Mico manicorensis

- Rio Acarí marmoset, Mico acariensis

- Rondon's marmoset, Mico rondoni

- Genus Callithrix

- Common marmoset, Callithrix jacchus

- Black-tufted marmoset, Callithrix penicillata

- Wied's marmoset, Callithrix kuhlii

- White-headed marmoset, Callithrix geoffroyi

- Buffy-tufted marmoset, Callithrix aurita

- Buffy-headed marmoset, Callithrix flaviceps

- Genus Callimico

- Goeldi's marmoset, Callimico goeldii

- Genus Saguinus

- Black-mantled tamarin, Saguinus nigricollis

- Brown-mantled tamarin, Saguinus fuscicollis

- White-mantled tamarin, Saguinus melanoleucus

- Golden-mantled tamarin, Saguinus tripartitus

- Moustached tamarin, Saguinus mystax

- White-lipped tamarin, Saguinus labiatus

- Emperor tamarin, Saguinus imperator

- Red-handed tamarin, Saguinus midas

- Black tamarin, Saguinus niger

- Mottle-faced tamarin, Saguinus inustus

- Pied tamarin, Saguinus bicolor

- Martins's tamarin, Saguinus martinsi

- White-footed tamarin, Saguinus leucopus

- Cottontop tamarin, Saguinus oedipus

- Geoffroy's tamarin, Saguinus geoffroyi

- Genus Leontopithecus

- Golden lion tamarin, Leontopithecus rosalia

- Golden-headed lion tamarin, Leontopithecus chrysomelas

- Black lion tamarin, Leontopithecus chrysopygus

- Superagui lion tamarin, Leontopithecus caissara

- Genus Cebuella

References

| Wikispecies has information related to: Callitrichinae |

- ↑ Groves, C.P. (2005). Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 129–136. OCLC 62265494. ISBN 0-801-88221-4.

- ↑ Rylands AB & Mittermeier RA (2009). "The Diversity of the New World Primates (Platyrrhini)". In Garber PA, Estrada A, Bicca-Marques JC, Heymann EW & Strier KB. South American Primates: Comparative Perspectives in the Study of Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. Springer. pp. 23–54. ISBN 978-0-387-78704-6.

- ↑ Hershkovitz, P. Living New World Monkeys (Platyrrhini) with an Introduction to the Primates. University of Chicago 1977.

- 1 2 Ford, S. M. (1980-01-01). "Callitrichids as phyletic dwarfs, and the place of the Callitrichidae in Platyrrhini". Primates. 21 (1): 31–43. doi:10.1007/BF02383822. ISSN 0032-8332.

- ↑ Naish, Darren. Marmosets and tamarins: dwarfed monkeys of the South American tropics. Scientific American November 27, 2012

- ↑ Harrison, M. L.; Tardif, S. D. (1994). "Social implications of gummivory in marmosets". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 95 (4): 399–408. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330950404. PMID 7864061.

- ↑ Sussman, R.W. (2003). "Chapter 1: Ecology: General Principles". Primate Ecology and Social Structure. Pearson Custom Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-536-74363-3.

- ↑ Cleveland and Snowdon. Social development during the first twenty weeks in the cotton-top tamarin ( Saguinus o. oedipus). Animal Behaviour (1984) vol. 32 (2) pp. 432-444