Bezant

Bezant is a medieval term for a gold coin. Medievally originally it meant the gold coins produced by the government of the Byzantine Empire. The word was derived from the Greek Byzantium. Later in the medieval era among the Latins the scope of the word was expanded to gold coins produced by Arabic governments.

Medieval history

Gold coins were rarely minted in early medieval Western Europe, up until the later 13th century; silver and bronze were the metals of choice for money. Gold coins were almost continually produced by the Byzantines and medieval Arabs. These circulated in Western European trade in smallish numbers, originating from the coinage mints of the Eastern Mediterranean. In Western Europe, the gold coins of Byzantine currency were highly prized. These gold coins were commonly called bezants. The first "bezants" were the Byzantine solidi coins; later the name was applied to the hyperpyra, which replaced the solidi in Constantinople in the late 11th century. The name hyperpyron was used by the late medieval Greeks, while the name bezant was used by the late medieval Latin merchants for the same coin. The Italians also used the name perpero or pipero for the same coin (an abridgement of the name hyperpyron).

Medievally from the 12th century onward (if not earlier), the Western European term bezant also meant the gold dinar coins minted by Islamic governments. The Islamic coins were originally modelled on the Byzantine solidus during the early years after the onset of Islam. The term bezant was used in the late medieval Republic of Venice to refer to the Egyptian gold dinar. Marco Polo used the term bezant in the account of his travels to East Asia when describing the currencies of the Yuan Empire around the year 1300.[1] His descriptions were based on the conversion of 1 bezant = 20 groats = 133⅓ tornesel.[1] An Italian merchant's handbook dated about 1340, Pratica della mercatura by Pegolotti, used the term bisant for coins of North Africa (including Tunis and Tripoli), Cyprus, Armenia and Tabriz (in today's northwestern Iran), whereas it used the term perpero | pipero for the Byzantine bizant.[2]

Although usually the medieval "bezant" was a gold coin, medieval Latin texts have also silver coin bezants. The silver bezants were often called "white bezants".[3] Occasionally in Latin they were called "miliaresion bezants" | "miliarense bezants". Like the gold bezants, the silver bezants by definition were issuances by the Byzantine government or by an Arabic government, and not by a Latin government, and the usage of the term was confined to the Latin West.

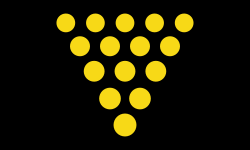

Bezants in heraldry

In heraldry, a roundel of a gold colour is referred to as a bezant, in reference to the coin. Like many heraldic charges, the bezant originated during the crusading era, when Western European knights first came into contact with Byzantine gold coins, and were perhaps struck with their fine quality and purity. During the Fourth Crusade the city of Constantinople, was sacked by Western forces. During this sacking of the richest city of Europe, the gold bezant would have been very much in evidence, many of the knights no doubt having helped themselves very liberally to the booty. This event took place at the very dawn of the widespread adoption of arms by the knightly class, and thus it may have been an obvious symbol for many returned crusaders to use in their new arms. When arms are strewn with bezants, the term bezantée or bezanty is used.

References

- 1 2 Yule, Henry; Cordier, Henri. The Travels of Marco Polo: The Complete Yule-Cordier Edition. Third edition (1903), revised and updated by Henri Cordier. Plain Label Books. p. 1226-27. (ISBN 1-60303-615-6)

- ↑ La Pratica della Mercatura, by Francesco Balducci Pegolotti, dated 1343, full text online in Italian at MedievalAcademy.org.

- ↑ Bezant @ The Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Difussion of Useful Knowledge, Volume 4, year 1835.

- ↑ Arms of Russell of Kingston Russell & Dyrham. Sir John Russell was a favoured courtier of King Henry III, granted by the King the barony of Newmarch c. 1216.