Burzio's generalization

In generative linguistics, Burzio's generalization is the observation that a verb can assign a theta role to its subject position if and only if it can assign an accusative case to its object. Accordingly, if a verb does not assign a theta role to its subject, then it does not assign accusative case to its object. The generalization is named after Italian linguist Luigi Burzio, based on work published in the 1980s, but the seeds of the idea are found in earlier scholarship. The generalization can be logically written in the following equation:

Ѳ ↔ A

Where: Ѳ = Subject Theta Role

A = Accusative Case

Burzio’s generalization has two major consequences:

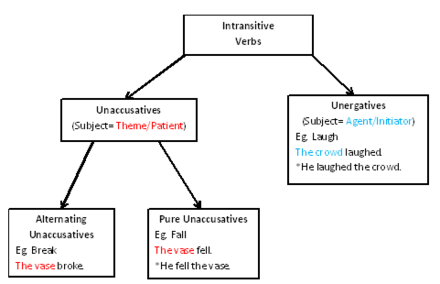

- Burzio's generalization recognizes two classes of intransitive verbs. With ergative intransitive verbs (e.g., fall), the single argument bears the theme theta role, and the subject is understood as the undergoer of the action. For example, in the sentence Emily fell, the subject Emily undergoes the action of falling. With unergative transitive verbs (e.g., laugh), the single argument bears the agent theta role and is understood as the doer of the action. For example, in the sentence Emily laughed, the subject Emily performs the action.

- Burzio's generalization establishes a parallel between unaccusative verbs (referred to as ergative verbs by Burzio[1]) and passives, neither of which assign a subject theta role or accusative case.

Burzio describes the intransitive occurrence of ergative verbs in the generalization that bears his name:[2]

“All and only the verbs that can assign a theta-role to the subject can assign Accusative Case to an object.” [3]

Two Classes of Intransitive Verbs

Intransitives

Burzio’s observations led to two separate classes of intransitive verbs.[4] Burzio claimed that intransitives are not homogenous and exemplified this observation with the following data from Italian:[5]

(1a) Giovanni arriv-a Giovanni arrive-3SG.PRS. 'Giovanni arrives' (Burizo 1986: 20 (1a))

(1b) Giovanni telefon-a Giovanni telephone-3SG.PRS. 'Giovanni telephones' (Burizo 1986: 20 (1b))

Both of the verbs in 1a and 1b are classified as intransitives, they take only one predicate. However, what led Burzio to claim that the class of intransitives should be further divided was the distribution of Ne (of-them).[6]

(2a) Ne arriv-ano molt-i of-them arrive-3PL.PRS. many-M.PL. 'Many of them arrive' (Burizo 1986: 20 (2a))

(2b) *Ne telefon-a molt-i of them telephone-3SG.PRS. many-M.PL. 'Many of them telephone' (Burizo 1986: 20 (2b))

The different behaviour of these two intransitive verbs led to the hypothesis that the class of verbs known as intransitives were divided. Burzio argued that due to the grammatical differences between 2a and 2b, the underlying structures of 1a and 1b must be different.

In Italian, it is assumed that there is free subject inversion, which means that if a subject appears pre-verb then it will have a post-verb counterpart. The data in (3) demonstrates this assumption:

(3a) Molt-i espert-i arriver-anno.

Many-M.PL. expert-M.pl. arrive-3PL.FUT.

'Many experts will arrive'.[7]

(3b) Arriver-anno molt-i espert-i.

Arrive-3PL.FUT. many-M.PL. expert-M.PL.

'Many experts will arrive.'[8]

Burzio classified the subjects such as in 3b as i-subjects (inverted subjects).[9] It turns out that Ne-Cliticization (Ne-Cl) is only possible with a direct object, but upon further observation Ne-Cl is also possible with i-subjects that are related to a direct object, such is the case with inherently passive verbs.

The distribution of Ne and auxiliary "essere" motivated the existence of a class of intransitive verbs named ergative verbs. This class of verbs subcategorizes for direct objects and does not assign agent theta roles. The deep structure (d-structure) objects are equal to the surface structure (s-structure) subjects. A distributional test for ergativity is whether or not it can take a Ne-Cl (see distributional tests below).

The following flow chart depicts the difference between the two types of intransitive verbs; unaccusative and unergative. Unaccusative verbs are subdivided into ergative intransitive verbs (depicted as "pure unaccusatives") and alternating unaccusatives. For more information on alternating unaccusatives see causative alternation.

Motivation for Burzio's Generalization

Burzio’s generalization stems from two important observations:

- Why, if verbs should assign accusative Case to their objects, does the determiner phrase (DP) that is the complement to an unaccusative verb not receive accusative case.

- Unaccusative verbs lack an (agent) theta role [11]

Assignment of Theta Role and Case

Theta Role Assignment

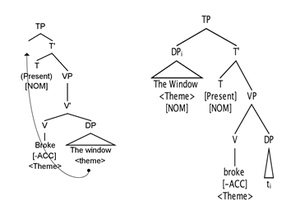

Theta roles (or thematic roles[12]) are bundles of Thematic relations that cluster on one argument.[13] Theta roles are assigned in the d-structure, which means that they take place before transformational rules (e.g., movement).[14] There are certain theta roles that are more commonly assigned to the subject such as agent and theta roles that are more common to the object such as patient or theme. Subjects of ergative verbs bear a theta role that is common to objects, which leads to the hypothesis that in the d-structure the Determiner Phrase subject occupies the object position in the syntactic tree. The following is a theta grid for the Ergative verb fall, which has the argument structure V[DP___]:

Fall

Agent

DP |

The Theta Criterion ensures that there is a one-to-one mapping of theta roles to arguments by stating the following:

- Each argument is assigned one and only one theta role, and

- Each theta role must be assigned to an argument.

This is important in the context of Burzio's generalization because it requires that all arguments must take a theta role and all theta roles must be assigned. This means that if a verb has a theta role to assign it must assign it.

Theta Role Assignment (1980's to 2000)

In the 1980s, when Burzio was formulating this generalization; it was understood that the verb assigned the theta role to the subject. Since then, in light of new data such as idiom formation, it is now hypothesized that Voice Phrase assigns the theta role to the subject, and not the verb. In this article we have adopted that the verb assigns the theta role as it was when Burzio was formulating his generalization.

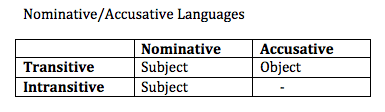

Assigning Case

Burzio's Generalization is observable in English, German, and many Romance languages due to a common Case system (Nominative/Accusative). In nominative/accusative languages the subject of both a transitive verb and an intransitive verb are assigned nominative Case, and only the object DP of a transitive verb will receive accusative Case. Case assignment is associated with local dependency and feature checking of a DP. All DP's must check for Case if and only if they are in the specifier or complement position of the Case assigner. The finite T assigns nominative Case to a subject DP in its specifier position. The verb (V) assigns accusative Case to a DP in the complement position. A preposition can also assign case (Prepositional Case) to a DP in the complement position.[16]

α assigns case to β if and only if:

α is a verb or preposition

β is a specifier/complement to α [17]

In the Italian language, identifying accusative Case has two requirements; the occurrence of third person accusatives like lo, la and accusative forms of me, te for the first and second person pronouns, differing from their nominative equivalents io and tu. He also states that ergative verbs do not have accusative Case and therefore do not assign accusative Case to the object. Below, the non-argument subject does not succeed at being correlated to a verbal argument.

a. * Gli cad-e me addosso.

to him fall-3SG.PRST me upon

It falls on him.

b.* Gliele scapp-ava

to-him-them escape-3SG.IMPF.

It escaped them from him.

c.* Arriv-a te

arrive-3SG.PRS. you

'It arrives you'

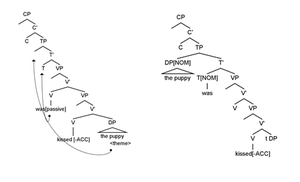

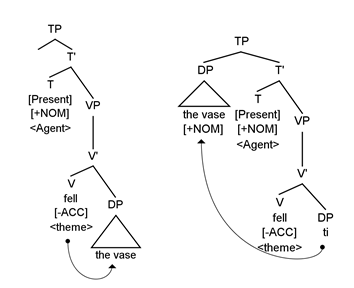

Parallel Between Passives and Unaccusative Verbs

Burzio's Generalization builds off of the cross linguistic similarities observed in passives and unaccusatives, where a verb fails to assign a theta role to the subject and cannot assign accusative Case to the object. These structures all undergo similar DP movement as a way to satisfy Extended Projection Principle and Case Theory. Extended Projection Principle states that all clauses must contain a DP subject and Case Theory states that all DP's must check for Case in the complement or specifier position. A theta role is not assigned to the subject position because the subject is underlyingly in the object position during theta role assignment (which happens in the d-structure). Therefore, it has a theta role that is typically given to objects, such as ‘’theme.’’ Verbs in these structures cannot assign accusative Case, therefore the DP must move to the empty specifier position of finite Tense (T) in order to fulfill the subject position and check for Case. Once the DP has moved to the specifier position of Tense Phrase (TP), nominative case is assigned to the DP by the T position. This occurs in the s-structure after the DP has moved from the object position.[20]

It should not be assumed that ergative verbs inherently do not have either accusative case or a subject theta role to assign. This is exemplified in the transitive counterparts of alternating unaccusatives. The ergative verb can act as a transitive and assigns both an agent theta role to the subject and accusative case to the object (see causative alternation) in an example such as, "John broke the vase." Burzio's Generalization refers only to intransitive ergative verbs such as "fall" that can not take a direct object like unergatives and alternating unaccusatives. For example, "The vase fell" cannot take a direct object ("*The vase fell the table.")

The generalization now becomes quite clear. In ergative verbs, if the verb does not assign a theta role to its subject (because in the d-structure this position is empty) then it also does not assign accusative case to its object (because this position is empty in the s-structure, due to DP movement). This is observable only in ergative intransitive verbs.[21]

Distributional Tests

There are two distributional tests that are used to determine if a verb is ergative; there-inversion and Ne-Cliticizaion. In each corresponding test, "there" or "ne" is inserted before the verb and the sentence is tested for grammaticality. Based on the grammaticality of the sentence the class of verb can be determined.

There-inversion

There-inversion is a distributional test introducing a different word order by inserting "there" before the verb. This insertion forces the object to remain underlyingly in the object position. Unaccusative verbs such as "arrive" will allow this alternative word order whereas unergative verbs such as "dance" will not. An unergative verb will appear to be ungrammatical because the subject is not generated in the object position. The example below is adapted from Andrew Carnie (2013).[22]

1a) *There danced three men at the palace. 1b) ?There arrived three men at the palace.

Ne-Cliticization

In Italian, Ne-Cliticization is a test to check if a verb is ergative. The example below is adapted from Liliane Haegeman.[23]

1a) Giovanni ne ha insultat-i due.

Giovanni of-them have-3G.PST. insult-M.PL.PST.PTCP. two.

'Giovanni has insulted two of them.'

1b)*Giovanni ne ha parl-ato a due.

Giovaani of them have-3G.PST. speak-M.SG.PST.PTCP. to two.

'Giovanni has spoken to two of them.'

In (1a)‘’due’’ is in the object position and therefore it is possible to have the partitive ‘’ne’’. In (1b) ‘’due’’is the complement to the preposition which results in the partitive ‘’ne’’ making the sentence ungrammatical.

(2) Ne furono arrest-ati molt-i.

of them be-3PL.REMPST. arrest-M.PL.PST.PTCP. many-M.PL.

'Many of them were arrested.'

In (2) there is a passive sentences with inverted post-verbal subjects. Ne-cliticization is possible if we assume that post-verbal subjects are in the object position.

(3) Ne arriv-ano molt-i.

of them arrive-3PL.PRS. many-M.PL.

'Many of them arrive.'

Ergatives are structurally the same as passives which leads us to expect that ne-cliticization is possible.

Contrasts to Burzio's Generalization

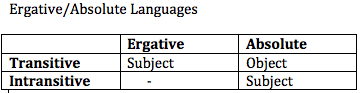

Contrasts to Burzio's generalization include ergative–absolutive languages, dative case marking, and English existential, raising, and weather verbs. These construction types are similar in that they all violate the bidirectional relationship in Burzio's generalization that exists between the subject theta role and assigning accusative Case to the object.

Ergative Absolute Languages

The Case system in ergative/absolute languages differs from the Romance languages that Burzio's Generalization is based on. In ergative/absolute system, the same case (absolutive) is assigned to the object of transitive verbs and subject of intransitive verbs. Ergative case is assigned to the subjects of transitive verbs. It should be noted that most languages do not strictly follow either Nom/Acc or Erg/Abs case systems but often use a combination of both systems in different circumstances. Subject constructions types (including passive and ergative construction), in languages such as Hindi, have verbs that do not assign accusative case to the object yet still acquire theta roles in the subject position. The inability of the verb to assign Case is evident by the object that undergoes movement to a higher clause to check for Case which is reflected in the agreement with auxiliaries. The following example is an ergative subject construction that assigns a theta role to the subject position and yet fails to assign Case to the object.[25]

Siitaa ne vah ghar khariidaa (thaa)

Sita-F-ERG that house-M buy-PERF-M be-PRS-M

"Sita had bought that house."[26]

Dative Case Marking

Icelandic is an example of a language that uses lexical categories to determine nominal morphology. Particular verbs known as quirky case require a certain case only on the nominals that have been assigned theta role and will obscure the underlying morphology. These verbs create unpredictable patterns of dative morphology assignment.[27]

Below are two examples from Esther Torrego [28] that show data case is assigned by a quirky case verb, finish. In example 1, the assignment of dative case is unpredictable by the verb as we would expect to see the object taking accusative case. As in example 2, the subject is taking the dative case where normally we would expect to see nominative case.

(1)Þeir luku kirkjunni.

they finished the-church.DAT

(2)Kirkjunni var lokið (af Jóni).

the-church.DAT was finished

These examples show that the assignment of accusative and nominative are undetectable morphologically speaking.

Verbs that fail to assign an external theta role

Verbs with dethematized subject positions, subjects without theta-roles, cannot be embedded by a control predicate in languages such as English, where pronouns cannot be dropped. Prominent examples are existential, raising, and weather verbs, which cannot assign theta-roles to their subject positions but still assign Case to their objects, conflicting with Burzio’s generalization. This is due to the fact that for example, weather verbs can take the cognate objects. Unergative verbs can assign case to its following position, whereas unaccusative ones cannot. The sentences below exemplify how weather verbs, intransitive unaccusative verbs, with cognate objects can assign Case to their object positions.[29]

1)It snowed an artificial kind of snow. 2)It rained acid rain.

Alternative Analyses

Ergative generalization

Construction types that violate the bidirectional relationship in Burzio’s generalization (see Hindi example above) provide evidence that a similar generalization can be made for such languages: the absence of a subject theta role implies that ergative case is unassigned. This is sometimes referred to as the ergative generalization or as Marantz's generalization after linguist Alec Marantz, who first proposed it. His generalization states that even when ergative case may go on the subject of an intransitive clause, ergative case will not appear on a derived subject.[30] Marantz suggests this inconsistency in Burzio’s generalization is accounted for by independent factors such as Universal Grammar and language specific construction types. Several attempts have been made to unify this generalization with Burzio's in a larger framework.

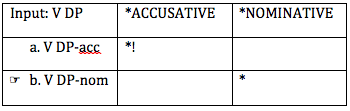

Optimality Theory

Burzio's Generalization can be proven with ranked and inviolable interacting constraints based on Optimality Theory. Markedness and Faithfulness constraints are ranked to select an optimal candidate. In an optimality-theory (OT) style of analysis, the argument of an ergative intransitive verb can potentially be assigned either nominative (NOM) or accusative case (ACC). A markedness constraint, which ranks ACC above NOM, prevents ACC from surfacing on the subject. A faithfulness constraint, which prohibits an argument from bearing multiple cases, prevents NOM and ACC from being assigned to the same argument. Case on the argument is ranked highly on the tableau. In addition, a faithfulness constraint (FAITHLEX, which requires the inherent Case-licensing must be checked) must be ranked highly in the tableau. Constraint definitions: *ACCUSATIVE: assign a violation mark to an unaccusative verb with accusative Case. *NOMINATIVE: assign a violation mark to an unaccusative verb with Nominative Case.[32]

Nominalization

Burzio believes that Case absorption of object case removes an agent project from the subject position which can apply from within the VP to the specifier of AP(-able) to the specifier of NP(-ity) to the specifier of the DP. It has been argued that lexical rules obey syntactic constraints and that feature-movement occurs within the lexicon.

Abbreviations

3- Third person ERG-Ergative F- Female FUT- Future IMPF- imperfect M- Masculine PERF - Perfect PST- Past PTCP- Participle PRS- present PL- Plural SG- Singular REMPST- Remote Past

References

- ↑ As this article is about Burzio's Generalization, we will adopt his terminology and refer to unaccusatives as ergative verbs

- ↑ Mackenzie, Ian (2006). Unaccusative Verbs in Romance Languages. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 187.

- ↑ Burzio, Luigi (1986). Italian Syntax. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel publishing Company.

- ↑ Hoekstra, Teun (200). "The Nature of Verbs and Burzio's Generalization" Arguments and Case: Explaining Burzio's Generalization. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 57.

- ↑ Burzio, Luigi (1986). Italian Syntax. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Company. p. 20.

- ↑ Burzio, Luigi (1986). Italian Syntax. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Company. p. 20.

- ↑ Burzio, Luigi (1986). Italian Syntax. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Company. p. 21.

- ↑ Burzio, Luigi (1986). Italian Syntax. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Company. p. 21.

- ↑ Burzio, Luigi (1986). Italian Syntax. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Company. p. 22.

- ↑ Schäfer, Florian (2009). The Causative Alternation. Language and Linguistic Compass. p. 641.

- ↑ Woolford, Ellen (2003). "Burzio's Generalization, Markedness, and locality Constraints on Nominative Objects". New Perspectives on Case Theory. 301.

- ↑ Sobin, Nicholas (2011). Syntactic Analysis: The Basics. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 54.

- ↑ Carnie, Andrew (2013). Syntax. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 232.

- ↑ Carnie, Andrew (2013). Syntax. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 325.

- ↑ Carnie, Andrew (2013) Syntax: A Generative Introduction. 3rd edition. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 340

- ↑ Carnie, Andrew (2013) Syntax: A Generative Introduction. 3rd edition. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. Chapter 11

- ↑ Torrego, Esther. (2011) "Draft of a chapter to appear in C. Boeckx (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Minimalism. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 4

- ↑ Carnie, Andrew (2013). Syntax. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p 334

- ↑ Schäfer, Florian. 2009. "The Causative Alternation." Language and Linguistics Compass 3.2: 641

- ↑ Carnie, Andrew (2013) Syntax: A Generative Introduction. 3rd edition. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. Chapter 11

- ↑ Carnie, Andrew (2013). Syntax: A Generative Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell.

- ↑ Carnie, Andrew (2013). Syntax. West Sussex, Uk: Blackwell Publishing.

- ↑ Haegeman, Liliane. (1985) "The Get-Passive and Burzio's Generalization". Lingua 64-65 (example 29a,b,c,d).

- ↑ Carnie, Andrew (2013) Syntax: A Generative Introduction. 3rd edition. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 340

- ↑ Reuland, Eric J (2000). ed. Arguments and Case: Explaining Burzio's Generalization. Vol. 34. John Benjamins. p 79

- ↑ Reuland, Eric J (2000). ed. Arguments and Case: Explaining Burzio's Generalization. Vol. 34. John Benjamins. p 81

- ↑ Torrego, Esther. (2011) "Draft of a chapter to appear in C. Boeckx (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Minimalism. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 9

- ↑ Torrego, Esther (2011). "Draft of a chapter to appear in C. Boeckx (ed.)" The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Minimalism. Oxford University Press. p. 9.

- ↑ Ura, Hiroyuki (2003). "Why Does It Behoove the Verb Behoove Not to Behave in Behalf of Burzio's Generalization?--An Analogy with Weather Verbs". 人文論究. 53 (2): 84.

- ↑ Marantz, Alec (1992). "Case and Licensing". Proceedings – Eastern States Conference on Linguistics (ESCOL. 8: 234–53.

- ↑ Legendre, Géraldine, Jane Barbara Grimshaw, and Sten Vikner, eds. Optimality-theoretic syntax. Bradford Books, 2001. p 518

- ↑ Legendre, Géraldine, Jane Barbara Grimshaw, and Sten Vikner, eds. Optimality-theoretic syntax. Bradford Books, 2001. p 518