Bundjalung

| Bundjalung people | |

|---|---|

|

Aka: Badjalang (Tindale)(Horton) Bandjalang (SIL) | |

|

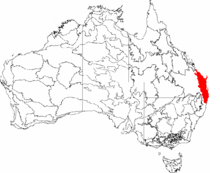

South Eastern Queensland bioregion | |

| Hierarchy | |

| Language family: | Pama–Nyungan |

| Language branch: | Bandjalangic |

| Language group: | Bundjalung |

| Group dialects: |

Arakwal[1] Baryulgal[2] Dinggabal[2] Gidabal[3] Minjungbal[2] Nganduwal[2] Njangbal[2] Waalubal[2] Wiyabal(a.k.a. Widje[4]) Wudjeebal.[2] Yugumbir[3] |

| Area (approx. 6,000 sq. km) | |

| Location: |

North-eastern New South Wales |

| Coordinates: | 29°15′S 152°55′E / 29.250°S 152.917°ECoordinates: 29°15′S 152°55′E / 29.250°S 152.917°E |

| Mountains: |

McPherson Range Mount Warning (a.k.a. Wollumbin ) |

| Rivers[4] |

Lower reaches of Clarence River a.k.a. Breimba;[5] Tweed River; Richmond River |

| Other geological: | Cape Byron |

| Urban areas:[4] |

Ballina Beaudesert Casino Gold Coast Grafton Lismore Tabulam Tweed Heads Warwick Woodenbong |

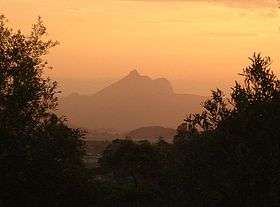

The Bundjalung people (a.k.a. Bunjalung, Badjalang & Bandjalang) are Aboriginal Australians who are the original custodians of northern coastal areas of New South Wales (Australia), located approximately 550 kilometres (340 mi) northeast of Sydney, an area that includes the Bundjalung National Park and Mount Warning (known to the Bundjalung people as Wollumbin ("rainmaker")[6]).

Bundjalung people all share in common descent from ancestors who once spoke as their first, preferred language, one or more of the dialects of the Bandjalang language.

The Arakwal people are a sub-group or tribe of the Bundjalung people of Byron Bay.[7]

Country

Norman Tindale's (1974) Catalogue of Australian Aboriginal tribes identifies the identifying Baryulgal dialect (Badjalang) country as follows:[4]

"From northern bank of Clarence River to Richmond River; at Ballina; inland to Tabulam and Baryugil, up to Bundaberg."

Religious beliefs

The Bundjalung people believe the spirits of wounded warriors are present within the mountains, their injuries having manifested themselves as scars on the mountainside, and thunderstorms in the mountains recall the sounds of those warriors' battles.[6]

Wollumbin itself is the site at which one of the chief warriors lies, and it is said his face can still be seen in the mountain's rocks when viewed from the north.[6]

Much of the Bundjalung peoples culture and heritage continues to be celebrated.[8]

Nowadays people gather annually in the Bundjalung national park as a community to celebrate as a Bundjalung People's Gathering.[8]

"We want to celebrate our Aboriginal traditions and customs. We want to share them with other people and show them our beliefs and our culture is still alive today, it hasn't been lost" - Chris Phillips, event organizer"

On these occasions traditional garments are often worn by the Bundjalung peoples, who partake in custodial dances and other performances.[8]

Land claim

In November 2007 the Federal Court made a positive determination regarding the existence of native title within Githabul country.[9]

Musical instruments

| Place names | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | |||||

| Instrument | Usage | ||||

| 1 | |||||

| Didjeridu ("Didgeridoo") | Traditionally the Didjeridu originated in Arnhem Land on the northern coastline of the Northern Territory, Australia, where it is called a 'yidaki or yiraki' in the Local Aboriginal language. The Didjeridu has some similarity to bamboo trumpets and even bronze horns developed in other cultures, though it pre-dates most of these by many millennia. | ||||

| 2 | |||||

| Gum leaf | Traditionally the leaf from a tree of the Eucalyptus family is used by Bundjalung Nation tribes as a musical instrument by holding against the lips and blowing to create a resonant vibration. Originally used in the imitation of bird-calls. | ||||

| 3 | |||||

| Bull-roarer | A bullroarer, rhombus, or turndun is a primitive ritual musical instrument, made of a small flat slip of wood, through a hole in one end of which a string is passed; swung round rapidly it makes a booming, humming noise.

It is used as the Aboriginal "bush telephone" to communicate over extended or long-distances. The instrument is called a "Burliwarni", "Ngurrarngay" and "Muypak". Bullroarers are given to men during their naming ceremonies. The bullroarer itself is not unique to Australia. It has been used in ancient Egypt and by the Inuit of Northern Canada. In New Guinea, in some of the islands of the Torres Strait (where it is swung as a fishing-charm), in Sri Lanka (where it is used as a toy and figures as a sacred instrument at Buddhist festivals), and in Sumatra (where it is used to induce the demons to carry off the soul of a woman, and so drive her mad), the bullroarer is also found. Sometimes, as among the Minangkabos of Sumatra, it is made of the frontal bone of a man renowned for his bravery. Bull-roarers are considered secret men's business by some Aboriginal tribal groups, and hence taboo for women, children, non-initiated men and/or outsiders to even hear. They are used in men's initiation ceremonies accompanied by the didgeridoo, and the sound they produced is considered by some Indigenous cultures to represent the sound of the Rainbow Serpent. The sound of the bull-roarer is said to be the voice of an ancestor, a spirit, or a deity. In the cultures of South-East Australia, the sound of the bullroarer is the voice of Daramulan, and a successful bullroarer can only be made if it has been cut from a tree containing his spirit. | ||||

| 4 | |||||

| Clap-sticks | Clapsticks are traditionally used by Bundjalung Nation tribes during a variety of ceremonies, ranging from secret ceremonies to rain-making ceremonies.

Traditionally 'Clapsticks' are percussion instruments — a must in every aboriginal performance. By varying the position of percussion, the sound will vary in pitch and tone, from soft to loud, from heartbeat, clapping,...to a metallic clank and have "echo". The aboriginal art on clap-sticks represents the local flora & fauna.[10] | ||||

| 5 | |||||

| Emu-caller | Emu callers are short, one foot, about 30 cm long didgeridoos. The emu callers were traditionally used by Bundjalung Nation tribes when hunting Eastern Australia Coastal Emus (Dromaius novaehollandiae). When striking the emu-caller at one end with the open palm it sounds like an emu. This decoy attracts the bird out of the bush making it an easy prey.[10] | ||||

Medicine

Spiritual medicine

Throughout Australia, Aborigines believe that serious illness and death is caused by spirits or persons who intentionally and deliberately cause or inflict harm towards others. Even trivial ailments, or accidents such as falling from a tree, are often attributed to malevolence. Aboriginal cultural cosmology is too constraining in meaning to allow the possibility of accidental injury and death, and when someone succumbed to misfortune, a woman or man versed in magic is called in to identify the culprit.

These spiritual doctors ware men and women of great wisdom and stature with immense power. Trained from an early age by their elders and initiated into the deepest of tribal secrets, they are the supreme authorities on spiritual matters. They can visit the skies, witness events from afar, and fight with serpents. Only they can pronounce the cause of serious illness or death, and only they, by performing sacred rites, can effect a cure.

Medicine men and women usually employ plants and herbs in their rites, occasionally practising secular medicine.

Secular medicine

The healing of trivial non-spiritual complaints, using herbs and other remedies, is still practiced by most Aboriginal People, although older women were usually the experts. To ensure success, plants and magic were often prescribed side-by-side.

Plants ware prepared as remedies in a number of ways. Leafy branches are often placed over a fire while the patient squats on top and inhaled the steam. Sprigs of aromatic leaves might be crushed and inhaled, inserted into the nasal septum, or prepared into a pillow on which the patient sleeps. To make an infusion, leaves or bark are crushed and soaked in water (sometimes for a very long time), which is then drunk, or washed over the body. Ointment is prepared by mixing crushed leaves with animal fat. Other external treatment includes rubbing down the patient with crushed seed paste, fruit pulp or animal oil, or dripping milky sap or a gummy solution over them. Most plant medicines are externally applied.

Medicine plants are always common plants. Aboriginal People carried no medicine kits and have remedies that grow at hand when needed. If a preferred herb is unavailable, there is usually a local substitute. Except for ointments, which were made by mixing crushed leaves with animal fat, medicines are rarely mixed. Very occasionally two plants are used together.

Aboriginal medicines are never quantified;— there are no measured doses or specific times of treatment. Since most remedies are applied externally, there is little risk of overdosing. Some medicines are known to vary in strength with the seasons. One area of Aboriginal medicine with no obvious Western parallel was baby medicine. Newborn babies are steamed or rubbed with oils to render them stronger. Often, mothers are also steamed.

A notable feature of Aboriginal medicine is the importance placed upon oil as a healing agent, an importance that passed to European colonists, and is reflected today in the continuing popularity of Australian Blue Cypress oil (Callitris intratropica), Eucalyptus oil, Emu oil, Goanna oil, Mutton Bird oil, Snake oil and Tea tree oil (Melaleuca oil).

Earth, mud, sand, and termite dirt are also taken as medicines. In many parts of Australia, wounds are dressed with dirt or ash. Arnhem Land aboriginal people eat small balls of white clay and pieces of termite mound to cure diarrhoea and stomach upsets.[11]

| Bush medicine | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| # | |||

| Medicine | Ailment | Treatment | |

| 1 | |||

| Gum | Burns, wounds and diarrhoea. | Traditionally, the indigenous native Bundjalung Nation Aboriginals of eastern Australia would use the resin from the trunk of a eucalyptus gum tree to treat burns, wounds and diarrhoea. The eucalyptus tree gum is high in tannin, a common astringent also found in tea-leaves and still used for treating burns. | |

| 2 | |||

| Tea tree leaves (Melaleuca alternifolia) | Wounds, infections, coughs, colds, sore throats, skin ailments | Traditionally, the indigenous native Bundjalung Nation Aboriginals of eastern Australia exposed to harsh conditions with little or no protection were observed by Europeans crushing tea tree leaf and binding it over wounds and infections with paper bark strapping. The results were staggering, infections are controlled and wounds heal rapidly.

In addition, the indigenous native Bundjalung Nation Aboriginal people use "tea trees" as a traditional medicine by inhaling the oils from the crushed leaves to treat coughs and colds. Furthermore, tea tree leaves are soaked to make an infusion to treat sore throats or skin ailments. Almost everywhere in Aboriginal Australia, herbs that were soaked in water are now boiled over fires. Aboriginal people today rarely distinguish this from a traditional practice, although they know the billycan is a white man's innovation. Boiling is much quicker than overnight soaking but it may destroy some active ingredients and increase the potency in solution of others. | |

| 3 | |||

| Paperbark | Headache | Traditionally, indigenous native Bundjalung Nation Aboriginals would chew young paperbark leaves to alleviate headache. | |

| 4 | |||

| Emu oil (Dromaius Novae-Hollandiae) | Psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis; a variety of skin conditions: bruises, burns, eczema, sun-dried skin, painful joints, swollen muscles | Traditionally, indigenous native Bundjalung Nation Aboriginals would massage emu oil into the skin to promote wound healing and to alleviate pain and disability from musculo-skeletal disorders.

The oil was collected by either hanging the emu skin from a tree or wrapping it around an affected area and allowing the heat of the sun to liquefy the emu fat to enhance absorption or penetration into the skin. An adult emu (15 months old) weighing 45 kg carries up to 10 kg of body fat, from which 7-8 L of a thick oil is obtained by rendering at temperatures up to 15 °C. | |

Notable Bundjalung people

Notable Bundjalung people include:

- Troy Cassar-Daley – born at Grafton to an Aboriginal mother and a Maltese-Australian father.[12]

- Ruby Langford Ginibi – author, lecturer in Aboriginal history, culture and politics, whose grandfather 'Sam', in a game of cricket in 1928 at Lismore, became one of only two Aboriginal cricketers to ever get Sir Donald Bradman out.[13]

- Anthony Mundine – professional boxer and multiple-time world champion. He is also a former New South Wales State of Origin representative footballer who played for St. George Illawarra Dragons and Brisbane Broncos in the Australian NRL. Before his move to boxing he was the highest paid player in the NRL.

- Warren Mundine – an advisor to the current Prime Minister, former National President of the Australian Labor Party and also a Director of the Australian Indigenous Education Foundation.

- Mark Olive – also known as the 'Black Olive' & 'Bush food crusader', a Wollongong born chef who trained in Europe, with over twenty years cooking experience, and he has his own pay TV indigenous cooking show, The Outback Cafe and is also the author of cookbooks such as Olive's Outback Cafe: A Taste of Australia.

- Johnny Jarrett (Patten) – former Australian Bantamweight boxing champion (1958 - 1962).

- Wes Patten – actor, television host, and former NRL player with the South Sydney Rabbitohs, St.George Dragons, Balmain Tigers and Gold Coast Chargers. Roles in television and film include playing opposite Cate Blanchett in Heartland (1994) and Hugo Weaving in Dirt Water Dynasty (1988). Other roles include stints on A Country Practice, Wills & Burke, and G.P.

- Albert Torrens – a former international rugby league footballer who played for the Manly-Warringah Sea Eagles, Northern Eagles and St. George Illawarra Dragons in the Australian NRL and for the Huddersfield Giants in the European Super League.

- Bronwyn Bancroft (born 1958) is an Australian artist, notable for being amongst the first Australian fashion designers invited to show her work in Paris. Born in Tenterfield, New South Wales, and trained in Canberra and Sydney, Bancroft worked as a fashion designer, and is an artist, illustrator, and arts administrator.

- Joyce Clague - political activist

See also

References

- ↑ "Bunjalung of Byron Bay (Arakwal) Indigenous Land Use Agreement". Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sharpe, Margaret C. (1994). "An all-dialect dictionary of Banjalang, an Australian language which is still in use."

- 1 2 Ethnlogue.com Accessed 20 May 2008

- 1 2 3 4 Tindale, Norman (1974) "Badjalang" in his Catalogue of Australian Aboriginal Tribes. South Australian Museum

- ↑ Bunjalung Jugun (Bunjalung Country), Jennifer Hoff, Richmond River Historical Society, 2006, ISBN 1-875474-24-2, citing Yamba Yesterday, Howland and Lee, Yamba Centenary Committee, 1985

- 1 2 3 Crossing the Great Dividing Range Archived 6 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine. from the Australian. Government's Culture and Creation Portal, retrieved 16 May 2008

- ↑ "ATNS - Agreements, Treaties and Negotiated Settlements project". www.atns.net.au. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- 1 2 3 Celebrating Indigenous Spirit from Echo News retrieved 16 May 2008

- ↑ National Native Title Tribunal (2007) "Githabul Federal Native Title Determination Brochure" Archived 1 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Aboriginal Artifacts: bullroarers, emu-callers, clap-sticks; Paintings

- ↑ Traditional Aboriginal Bush Medicine - Aboriginal Art Online

- ↑ "Troy Cassar-Daley". Talking Heads. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 4 May 2009. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ↑ Ruby Langford Ginibi. "Ginibi, Ruby Langford, 1934-". Digital Collections — Audio (Interview: transcript of sound recording). Interview with Heimans, Frank. National Library of Australia. p. 1.

External links

- Badjalang portion of Norman Tinadle's Aboriginal Tribes of Australia map Accessed 21 May 2008

- Bundjalung of Byron Bay Aboriginal Corporation, representing the Bundjalung and Arakwal people, land and waters

- Bibliography of Bundjalung language and people resources, at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- Bibliography of Arakwal language and people resources, at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- "Australia's Sacred Sites Part 5 - Byron Bay" ABC Radio's Spirit of Things (October 2002; Accessed 21 May 2008

- A Walk in the Park Series: "New South Wales - Arakwal National Park" ABC Radio (December 2004) Accessed 21 May 2008

- "Badjalang" AusAnthrop Australian Aboriginal tribal database. Accessed 20 May 2008

- Bunjalung of Byron Bay (Arakwal) Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA) Accessed 21 May 2008

- New South Wales Department of Environment and Climate Change Aboriginal cultural heritage webpage Living on the frontier Accessed 21 May 2008

- New South Wales Department of Environment and Climate Change November 2007 Media Release Wollumbin Aboriginal Consultative Group Accessed 21 May 2008