Brown-headed cowbird

| Brown-headed cowbird | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult male | |

| |

| Adult female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Icteridae |

| Genus: | Molothrus |

| Species: | M. ater |

| Binomial name | |

| Molothrus ater (Boddaert, 1783) | |

| |

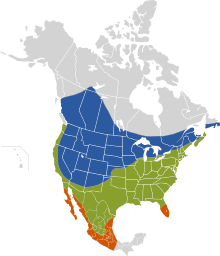

| Breeding range Year-round range Wintering range | |

The brown-headed cowbird (Molothrus ater) is a small obligate brood parasitic icterid of temperate to subtropical North America. They are permanent residents in the southern parts of their range; northern birds migrate to the southern United States and Mexico in winter, returning to their summer habitat around March or April.[2]

Etymology

The genus name Molothrus is from Ancient Greek molos, "struggle", and throsko, "to impregnate", and the specific ater is Latin for "dull black".[3] The English name "cowbird", first recorded in 1839, refers to this species often being seen near cattle.[4]

Description

The brown-headed cowbird is typical for an icterid in general shape, but is distinguished by a finch-like head and beak and is smaller than most icterids. The adult male is iridescent black in color with a brown head. The adult female is slightly smaller and is dull grey with a pale throat and very fine streaking on the underparts. The total length is 16–22 cm (6.3–8.7 in) and the average wingspan is 36 cm (14 in).[5] Body mass can range from 30–60 g (1.1–2.1 oz), with females averaging 38.8 g (1.37 oz) against the males' average of 49 g (1.7 oz).[6]

Ecology

The species lives in open or semi-open country and often travels in flocks, sometimes mixed with red-winged blackbirds (particularly in spring) and bobolinks (particularly in fall), as well as common grackles or European starlings.[2] These birds forage on the ground, often following grazing animals such as horses and cows to catch insects stirred up by the larger animals. They mainly eat seeds and insects.

Before European settlement, the brown-headed cowbird followed bison herds across the prairies. Their parasitic nesting behaviour complemented this nomadic lifestyle. Their numbers expanded with the clearing of forested areas and the introduction of new grazing animals by settlers across North America. Brown-headed cowbirds are now commonly seen at suburban birdfeeders.

Reproduction

The brown-headed cowbird is an obligate brood parasite: it lays its eggs in the nests of other small passerines (perching birds), particularly those that build cup-like nests. The brown-headed cowbird eggs have been documented in nests of at least 220 host species, including hummingbirds and raptors.[7][8] The young cowbird is fed by the host parents at the expense of their own young. Brown-headed cowbird females can lay 36 eggs in a season. More than 140 different species of birds are known to have raised young cowbirds.[9]

Unlike the common cuckoo, the brown-headed cowbird is not divided into gentes whose eggs imitate those of a particular host.

Some host species, such as the house finch, feed their young a vegetarian diet. This is unsuitable for young brown-headed cowbirds, meaning almost none survive to fledge.[10]

Male behavior and reproductive success

Social behaviors of cowbird males include aggressive, competitive singing bouts with other males and pair-bonding and monogamy with females.

By manipulating demographics so juveniles only had access to females, juvenile males developed atypical social behavior; they did not engage in the typical social singing bouts with other males, did not pair bond with females, and were promiscuous. This demonstrates that there is great flexibility in the behavior of cowbirds, and that the social environment is extremely important in structuring their behavior. Adult males housed with juvenile males were shown to have greater reproductive success compared to adult males housed with other adult males. Being housed with juvenile males honed the reproductive skills of the adult males by providing them with a more complex social environment.

This finding was further studied by comparing the behaviors and reproductive success of males exposed to a dynamic flock, consisting of changing individuals, with males exposed to a static group of individuals. The individuals that stayed with the same group (i.e., static flock) had a stable, predictable relationship between social behavior and reproductive success; the males that sang high amounts to females experienced the greatest reproductive success. The adult males that were exposed to a rotating roster of new individuals (i.e., dynamic flock) had an unpredictable relationship between social variables and reproductive success; these males were able to copulate using a much greater variety of social strategies. The males who lived in static flocks had high levels of consistency in their behaviors and reproductive success across multiple years, whereas the males in dynamic flocks experienced varying levels of dominance with other males, differing levels of singing to females, and differing levels of reproductive success.[11]

Brood parasitism

Behavior

Brown-headed cowbirds do not raise their own young, instead laying their eggs in the nests of other bird species. Because of this, cowbirds are not exposed to species-typical visual and auditory information like other birds. Despite this, cowbirds are able to develop species-typical singing, social, and breeding behaviors.[11]

Host response

The acceptance of a cowbird egg and rearing of a cowbird can be costly to a host species. In the American redstart, nests parasitized by cowbirds were found to have a higher rate of predation, likely due in part to the loud begging calls by the cowbird nestling, but also partly explained by the fact that nests likely to be parasitized are also more likely to be predated.[12]

Host species sometimes notice the cowbird egg, with different hosts reacting to the egg in different ways. Some, like the blue-gray gnatcatcher, abandon their nest, losing their own eggs as well. Some, like the American yellow warbler, bury the foreign egg under nest material, where it perishes.[13] And some, like the brown thrasher, physically eject of the egg from the nest.[8] Experiments with gray catbirds, a known cowbird host, have shown that this species rejects cowbird eggs more 95% of the time; for this species, the cost of accepting cowbird eggs (i.e. the loss of their own eggs or nestlings through starvation or the actions of the nestling cowbird) was far higher than the cost of rejecting those eggs (i.e. where the host might conceivably eject its own egg accidentally).[14] Brown-headed cowbird nestlings are also sometimes expelled from the nest. Nestlings of host species can also alter their behavior in response to the presence of a cowbird nestling. Song sparrow nestlings in parasitized nests alter their vocalizations in frequency and amplitude so that they resemble the cowbird nestling, and these nestlings tend to be fed equally often as nestlings in unparasitized nests.[15]

Parasite response

It seems that brown-headed cowbirds periodically check on their eggs and young after they have deposited them. Removal of the parasitic egg may trigger a retaliatory reaction termed "mafia behavior". According to a study by the Florida Museum of Natural History published in 1983, the cowbird returned to ransack the nests of a range of host species 56% of the time when their egg was removed. In addition, the cowbird also destroyed nests in a type of "farming behavior" to force the hosts to build new ones. The cowbirds then laid their eggs in the new nests 85% of the time.[16]

Human intervention

Humans sometimes engage in cowbird control programs, with the intention of protecting species negatively impacted by the cowbirds' brood parasitism. A study of nests of Bell's vireo highlighted a potential limitation of these control programs, demonstrating that removal of cowbirds from a site may create an unintended consequence of increasing cowbird productivity on that site, because with fewer cowbirds, fewer parasitized nests are deserted, resulting in greater nest success for cowbirds.[17]

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Molothrus ater". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- 1 2 Henninger, W.F. (1906). "A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio" (PDF). Wilson Bull. 18 (2): 47–60.

- ↑ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London, United Kingdom: Christopher Helm. pp. 58, 257. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ↑ "Cowbird". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Brown-headed Cowbird, Life History, All About Birds – Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved on 2013-03-09.

- ↑ CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (1992), ISBN 978-0849342585.

- ↑ Friedman and Kiff, Herbert and Lloyd F. (1985-05-16). "The parasitic cowbirds and their hosts". Proceedings of the Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology. 2 (4): 225–304.

- 1 2 Ortega, C.P. (1998) Cowbirds and Other Brood Parasites. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, ISBN 0816515271.

- ↑ Jaramillo, Alvaro; Peter Burke (1999). New World Blackbirds: The Iceterids. London: Christopher Helm. p. 382.

- ↑ Kozlovic, Daniel R.; Knapton, Richard W.; Barlow, Jon C. (1996). "Unsuitability of the House Finch as a Host of the Brown-Headed Cowbird" (PDF). The Condor. 96 (2). doi:10.2307/1369143. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

- 1 2 White, D.J.; Gersick, A.S.; Snyder-Mackler, N. (2012). "Social Networks and the Development of Social Skills in Cowbirds" (PDF). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 367 (1597): 1892–900. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0223.

- ↑ Hannon, Susan J.; Wilson, Scott; McCallum, Cindy A. (2009). "Does cowbird parasitism increase predation risk to American redstart nests?". Oikos. 118 (7): 1035–1043. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0706.2008.17383.x.

- ↑ Sealy, Spencer g. (April 1995). "Burial of cowbird eggs by parasitized yellow warblers: an empirical and experimental study". Animal Behaviour. The Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour. 49 (4): 877–889. doi:10.1006/anbe.1995.0120. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

- ↑ Lorenzana, J. C. (2001). "Fitness costs and benefits of cowbird egg ejection by Gray Catbirds". Behavioral Ecology. 12 (3): 325–329. doi:10.1093/beheco/12.3.325.

- ↑ Pagnucco, K.; Zanette, L.; Clinchy, M.; Leonard, M. L (2008). "Sheep in wolf's clothing: host nestling vocalizations resemble their cowbird competitor's". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 275 (1638): 1061–1065. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1706.

- ↑ Hoover, Jeffrey P.; . Robinson & Scott K. (2007). "Retaliatory mafia behavior by a parasitic cowbird favors host acceptance of parasitic eggs". PNAS. 104 (11): 4479–4483. doi:10.1073/pnas.0609710104.

- ↑ Kosciuch, Karl L.; Sandercock, Brett K. (2008). "Cowbird removals unexpectedly increase productivity of a brood parasite and the songbird host" (PDF). Ecological Applications. 18 (2): 537–548. doi:10.1890/07-0984.1. PMID 18488614.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brown-headed Cowbird. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Molothrus ater |

- "Brown-headed cowbird media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Brown-headed cowbird Information at Animal Diversity Web

- Brown-headed Cowbird photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Brown-headed cowbird - Molothrus ater - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter