Celtic Britons

The Ancient Britons were those ancient inhabitants of the island of Great Britain who spoke the Celtic Common Brittonic language, which diversified into a group of related Celtic languages such as Welsh, Cornish, Pictish, Cumbric and Breton. The Britons lived all over the island of Great Britain and on the surrounding islands and archipelagos such as the Orkneys, Shetlands, Hebrides and Isle of Man. Ireland was inhabited by a different group of Celts, speaking Goidelic (or Gaelic).

The coming of the Anglo-Saxons and Gaelic Celts from the 5th century AD onwards, and the resulting gradual spread of the collection of dialects that would become the English language and Scots Gaelic, between them eventually extinguished Brittonic from much of its former territory by the 12th century AD, leaving Brittonic speakers only in Wales, Cornwall and Brittany.

The term is usually used in reference to the people of Great Britain in the Iron Age (from approximately the 7th century BC), and through the Roman, Sub-Roman period, Middle Ages and the Tudor period,[1] although there is thought to have been little or no change to the genetic mixture at the start of the period, and relatively little by the end. During the 18th century however, and particularly after the Acts of Union 1707 the terms British and Briton would gradually come to be applied not just to the remaining Brittonic peoples themselves, but to all of the inhabitants of the United Kingdom,[2] including the English, Scottish and Northern Irish.

By about 750 AD much former Brittonic territory had been gradually absorbed by newcomers, in the form of the Anglo-Saxons (or English) and Gaelic speaking Scots, both of whom began to arrive from Continental Europe and Northern Ireland respectively in the decades following the End of Roman rule in Britain in the late 4th century AD.

However, numerous Brittonic peoples and polities continued to endure; Wales and the Welsh people remained independent and distinct after this, along with other pockets such as Kernow (Cornwall) and Dumnonia in south west England, the Kingdom of Strathclyde in southern Scotland and Cumbria, some Pictish kingdoms of central, eastern and northern Scotland such as Fortriu, as well as the Bretons in northern France, and the inhabitants of Britonia in north western Spain, both groups having migrated from Britain in the 5th century AD.[3] The first Britons probably all spoke a language that is now known as Common Brittonic which split during this period into the various descendant Brittonic languages: Welsh, Cumbric, Cornish, Breton and the related Pictish, all of which are still extant, apart from Cumbric and Pictish, although these latter two extinct languages have left extensive traces in the form of numerous place names and geographical features in northern England and Scotland.

The earliest evidence of the existence of the Britons and their language in historical sources dates to the 4th century BC, during the Iron Age, and the Britons were known to have traded with the Ancient Greeks, Phoenicians and Romans.[4] After the Roman conquest of Britain in the 1st century, a Romano-British culture emerged, and Latin and British Vulgar Latin coexisted with Brittonic.[5] Prior to, during and after the Roman era, the Britons lived throughout Britain south of the Firth of Forth. Their relationship with the Picts, who lived north of the Firth of Forth, has been the subject of much discussion, though most scholars accept that the Pictish language was indeed a form of Common Brittonic, rather than a separate Celtic language.[6]

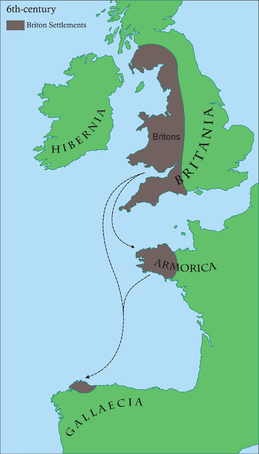

With the beginning of Anglo-Saxon settlement in the 5th century AD, the culture and language of the Britons fragmented and much of their territory was taken over by the Anglo-Saxons, or in the case of northern Britain and the Isle of Man, by Gaelic Scots. The extent to which this cultural and linguistic change was accompanied by wholesale changes in the population is still a matter of discussion. During this period some Britons migrated to mainland Europe and established significant settlements in Brittany (now part of France) as well as Britonia in modern Galicia, Spain.[4] By the 11th century, remaining Brittonic Celtic-speaking populations had split into distinct groups: the Welsh in Wales, the Cornish in Cornwall, the Bretons in Brittany, and the Brythonic people of the Hen Ogledd ("Old North") in southern Scotland and northern England in the Cumbric speaking Kingdom of Strathclyde. Common Brittonic developed into the distinct Brittonic languages: Welsh, Cumbric, Cornish and Breton.[4]

Name

The earliest known reference to the inhabitants of Britain seems to come from 4th century BC records of the voyage of Pytheas, a Greek geographer who made a voyage of exploration around the British Isles between 330 and 320 BC. Although none of his own writings remain, writers during the time of the Roman Empire made much reference to them. Pytheas called the islands collectively αἱ Βρεττανίαι (hai Brettaniai), which has been translated as the Brittanic Isles, and the peoples of these islands of Prettanike were called the Πρεττανοί (Prettanoi), Priteni, Pritani or Pretani. The group included Ireland, which was referred to as Ierne (Insula sacra "sacred island" as the Greeks interpreted it) "inhabited by the race of Hiberni" (gens hibernorum), and Britain as insula Albionum, "island of the Albions".[7][8] The term Pritani may have reached Pytheas from the Gauls, who possibly used it as their term for the inhabitants of the islands.[8]

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was originally compiled on the orders of King Alfred the Great in approximately 890, and subsequently maintained and added to by generations of anonymous scribes until the middle of the 12th century, starts with this sentence: "The island Britain is 800 miles long, and 200 miles broad, and there are in the island five nations: English, Welsh (or British, including the Cornish), Scottish, Pictish, and Latin. The first inhabitants were the Britons, who came from Armenia, and first peopled Britain southward." ("Armenia" is impossibly a mistaken transcription of Armorica, an area in Northwestern Gaul including modern Brittany.)[9]

The Latin name in the early Roman Empire period was Britanni or Brittanni, following the Roman conquest in AD 43.[10]

The Welsh word Brython was introduced into English usage by John Rhys in 1884 as a term unambiguously referring to the P-Celtic speakers of Great Britain, to complement Goidel; hence the adjective Brythonic referring to the group of languages.[11] "Brittonic languages" is a more recent coinage (first attested 1923 according to the Oxford English Dictionary) intended to refer to the ancient Britons specifically.

Language

The Britons spoke an Insular Celtic language known as Common Brittonic. Brittonic was spoken throughout the island of Britain (in modern terms, England, Wales and Scotland), as well as offshore islands such as the Isle of Man, Scilly Isles, Orkneys, Hebrides and Shetlands.[4][12] According to early mediaeval historical tradition, such as The Dream of Macsen Wledig, the post-Roman Celtic-speakers of Armorica were colonists from Britain, resulting in the Breton language, a language related to Welsh and identical to Cornish in the early period and still used today. Thus the area today is called Brittany (Br. Breizh, Fr. Bretagne, derived from Britannia).

Common Brittonic developed from the Insular branch of the Proto-Celtic language that developed in the British Isles after arriving from the continent in the 7th century BC. The language eventually began to diverge; some linguists have grouped subsequent developments as Western and Southwestern Brittonic languages. Western Brittonic developed into Welsh in Wales and the Cumbric language in the Hen Ogledd or "Old North" of Britain, while the Southwestern dialect became Cornish in Cornwall and South West England and Breton in Armorica. Pictish is now generally accepted to descend from Common Brittonic, rather than being a separate Celtic language. Welsh and Breton survive today; Cumbric became extinct in the 12th century. Cornish had become extinct by the 19th century but has been the subject of language revitalization since the 20th century.

Archaeology and art

Ideas about the development of British Iron Age culture changed greatly in the 20th century, and remain in development. Generally cultural exchange has tended to replace migration from the continent as the explanation for changes, although Aylesford-Swarling Pottery and the Arras culture of Yorkshire are examples of developments still thought to be linked to migration.

Although the La Tène style, which defines what is called Celtic art in the Iron Age, was late in arriving in Britain, after 300 BC the ancient British seem to have had generally similar cultural practices to the Celtic cultures nearest to them on the continent. There are significant differences in artistic styles, and the greatest period of what is known as the "Insular La Tène" style, surviving mostly in metalwork, was in the century or so before the Roman conquest, and perhaps the decades after it. By this time Celtic styles seem to have been in decline in continental Europe, even before Roman invasions.

An undercurrent of British influence is found in some artefacts from the Roman period, such as the Staffordshire Moorlands Pan, and it appears that it was from this, passing to Ireland in the late Roman and post-Roman period, that the "Celtic" element in Early Medieval Insular art derived.

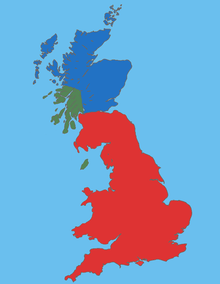

Territory

Throughout their existence, the territory inhabited by the Britons was composed of numerous ever-changing areas controlled by Brittonic tribes. The extent of their territory before and during the Roman period is unclear, but is generally believed to include the whole of the island of Great Britain, at least as far north as the Clyde-Forth isthmus, and if the Picts are included as Brittonic speaking people,[13] the entirety of Great Britain. The territory north of the Firth of Forth was largely inhabited by the Picts; little direct evidence has been left of the Pictish language, but place names and Pictish personal names recorded in the later Irish annals suggest it was indeed related to the Common Brittonic language rather than to the Goidelic (Gaelic) languages of the Irish, Scots and Manx; indeed their Goidelic Irish name, Cruithne, is cognate with Brythonic Priteni. Part of the Pictish territory was eventually absorbed into the Gaelic kingdoms of Dál Riata and Alba. The Isle of Man, Shetland, Hebrides and the Orkney islands were originally inhabited by Britons also, but eventually became respectively Manx and Scots Gaelic speaking territories.

In 43 the Roman Empire invaded Britain. The British tribes opposed the Roman legions for decades, but by 84 the Romans had decisively conquered southern Britain and had pushed into Brittonic areas of what would later become northern England and southern Scotland. In 122 they fortified the northern border with Hadrian's Wall, which spanned what is now Northern England. In 142 Roman forces pushed north again and began construction of the Antonine Wall, which ran between the Forth-Clyde isthmus, but they retreated back to Hadrian's Wall after only twenty years. Although the native Britons south of Hadrian's Wall mostly kept their land, they were subject to the Roman governors, whilst the Brittonic-Pictish Britons north of the wall remained fully independent. The Roman Empire retained control of "Britannia" until its departure about AD 410.

Shortly after the time of the Roman departure, the Germanic-speaking Anglo-Saxons began a migration to the Eastern coast of Britain, where they established their own kingdoms, and Gaelic speaking Scots migrating from what is today Ulster (Northern Ireland) did the same on the west coast of Scotland and the Isle of Man.[14][15] Eventually, the Brythonic language in these areas was replaced by the Old English of the Anglo-Saxons and Scots Gaelic.

At the same time, some Britons established themselves in what is now called Brittany. There they set up their own small kingdoms and the Breton language developed there from Brittonic Insular Celtic rather than Gaulish or Frankish. They also retained control of Wales, Cornwall and south Devon (Kernow/Dumnonia), as well as Northwest England and parts of Scotland, where kingdoms of the Hen Ogledd such as the Cumbric speaking Kingdom of Strathclyde (Ystrad Clud), Gododdin, Novant, Rheged Aeron(kingdom) and Eidyn, survived for some time in the south and east, as did Pictish kingdoms such as Fortriu, Kingdom of Cait and Kingdom of Ce in north eastern and northern Scotland.[16] A further colony, Britonia, was set up in Gallaecia in northwestern Hispania.

However, by the end of the 11th century, the Anglo-Saxons and Gaels had become the dominant cultural force in most of the Brittonic territory in Britain, and the language and culture of the native Britons was thereafter gradually replaced in those regions,[17] remaining only in Wales, Cornwall, parts of Cumbria, Strathclyde, Eastern Galloway and Brittany.

The Brittonic-Pictish polities in Scotland and northern England gradually fell to the English and Scots; Fortriu the largest Pictish kingdom had fallen by the early 10th century AD, with the Kingdom of Strathclyde (Strath-Clota) being the last of the Brittonic kingdoms of the north to fall in the 1090s, when it was effectively divided between England and Scotland.[18] Cornwall (Kernow, Dumnonia) had certainly been absorbed by England by the 1050s, although it retained a distinct Brittonic culture and language.[19] Britonia in Spanish Galicia seems to have disappeared by 900 AD.

Wales and Brittany remained independent for some time however, with Brittany finally being absorbed into France during the 1490s, and Wales united with England by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542 in the mid 16th century.

Wales, Cornwall and Brittany continued to retain a distinct Brittonic culture, identity and language, which they have maintained to the present day. The Welsh language and Breton language remain widely spoken, and the Cornish language, once close to extinction, has experienced a revival since the 20th century. The vast majority of place names and names of geographical features in Wales, Cornwall and Brittany are Brittonic, and Brittonic family and personal names remain common.

During the 19th century, a large number of Welsh farmers migrated to Patagonia in Argentina, forming a community called Y Wladfa, which today consists of over 80,000 Welsh speakers.

In addition, a Brittonic legacy remains in England, Scotland and Galicia in Spain,[20] in the form of often large numbers of Brittonic place and geographical names. Some examples of geographical Brittonic names survive in the names of rivers, such as the Thames, Clyde, Severn, Tyne, Wye, Exe, Dee, Tamar, Tweed, Avon, Trent, Tambre, Navia and River Forth. A number of place names in England and Scotland are of Brittonic rather than Anglo-Saxon or Gaelic origin, such as; London, Manchester, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Carlisle, Caithness, Aberdeen, Dundee, Barrow, Exeter, Lincoln, Dumbarton, Brent, Penge, Colchester, Durham, Dover, Pendleton, Leatherhead and York.

Britons

- King Arthur – Romano-British war leader of debatable historicity.

- Ambrosius Aurelianus (Emrys Wledig) – Romano-British War leader.

- Boudica – Queen of the Iceni, who led the failed rebellion against Roman occupation in 60 AD.

- Bonosus – a Romano-British military general and imperial pretender in 280 AD

- Cadwallon ap Cadfan – King of Gwynedd, fought against the Anglo-Saxons.

- Caratacus – a leader of the defence against the Roman conquest of Britain.

- Cartimandua – Queen of the Brigantes during and after the Roman invasion.

- Cassivellaunus – led the defence against Julius Caesar's second expedition to Britain in 54 BC.

- Conan Meriadoc – legendary founder of Brittany.

- Coel Hen – the "Old King Cole" of the popular nursery rhyme.

- Cogidubnus – a British client-king, later made a citizen of Rome and awarded Fishbourne Roman Palace.

- Commius – historical King of the Belgic nation of the Atrebates, initially in Gaul, then in Britannia, during the 1st century BC.

- Cunedda – post-Roman King and progenitor of the Kingdom of Gwynedd.

- Cunobelinus – historical King of southern Britain between the first and second Roman invasions,ruling from the stronghold of Camulodunon (modern Colchester).Called "King of the Britons" by Suetonius. The basis for Shakespeare's Cymbeline.[21]

- Gratianus – a Romano-British aristocrat and imperial usurper in 407

- King Lot – grandfather of St Kentigern, and eponymous king of Lothian.

- Mailoc – Bishop of Britonia (Galicia) in the 6th century AD

- Marcus Cunomorus – King Mark of Cornwall and Brittany

- Saint Patrick – a Romano-Briton and Christian missionary, who is the most generally recognized patron saint of Ireland or the Apostle of Ireland,

- Pelagius – an influential Christian monk and theologian, whose thought was branded heresy later in life.

- Prasutagus – husband of Boudica.

- Togodumnus – a leader of the defence against the Roman conquest of Britain.

- Urien – King of Rheged (modern Lancashire and Cumbria).

- Vortigern – warlord and King in the 5th century AD. Best known for inviting the Jutes to Kent.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Bradshaw & Roberts 2003, p. 1.

- ↑ Colley 1992, p. 1.

- ↑ b c Fraser 2009, p. 50.

- 1 2 3 4 Koch, pp. 291–292.

- ↑ Sawyer, P.H. (1998). From Roman Britain to Norman England. pp. 69–74. ISBN 0415178940.

- ↑ Forsyth, p. 9.

- ↑ Snyder, Christopher A. (2003). The Britons. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22260-X.

- 1 2 Foster (editor), R F; Donnchadh O Corrain, Professor of Irish History at University College Cork: Prehistoric and Early Christian Ireland (1 November 2001). The Oxford History of Ireland. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280202-X.

- ↑ "The Avalon Project". Yale Law School. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ↑ OED s.v. "Briton". See also Online Etymology Dictionary: Briton

- ↑ Online Etymology Dictionary: Brythonic

- ↑ While there have been attempts in the past to align the Pictish language with non-Celtic language, the current academic view is that it was Brittonic. See: Forsyth (1997) p. 37: "[T]he only acceptable conclusion is that, from the time of our earliest historical sources, there was only one language spoken in Pictland, the most northerly reflex of Brittonic."

- ↑ Forsyth 2006, p. 1447; Forsyth 1997; Fraser 2009, pp. 52–53; Woolf 2007, pp. 322–340

- ↑ John E Pattison. Is it necessary to assume an apartheid-like social structure in early Anglo-Saxon England? Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 275(1650), 2423–2429, 2008 doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0352

- ↑ Pattison, John E. (2011) "Integration versus Apartheid in post-Roman Britain: a Response to Thomas et al. (2008)," Human Biology: Vol. 83: Iss. 6, Article 9. pp. 715–733, 2011. Abstract available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol/vol83/iss6/9

- ↑ Broun, "Dunkeld", Broun, "National Identity", Forsyth, "Scotland to 1100", pp. 28–32, Woolf, "Constantine II"; cf. Bannerman, "Scottish Takeover", passim, representing the "traditional" view.

- ↑ Germanic invaders may not have ruled by apartheid New Scientist, 23 April 2008

- ↑ Charles-Edards, pp. 12, 575; Clarkson, pp. 12, 63-66, 154-58

- ↑ Williams, Ann and Martin, G. H. (tr.) (2002) Domesday Book: a complete translation, London: Penguin, pp. 341–357.

- ↑ Young, Simon (2002). Britonia: camiños novos. Noia: Toxosoutos. pp. 123–128. ISBN 978-84-95622-58-7.

- ↑ Crummy, Philip (1997) City of Victory; the story of Colchester – Britain's first Roman town. Published by Colchester Archaeological Trust (ISBN 1 897719 04 3)

References

- Forsyth, Katherine (1997). Language in Pictland (PDF). De Keltische Draak. ISBN 90-802785-5-6.

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO.

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

.jpg)