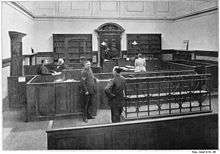

Bow Street Magistrates' Court

Bow Street Magistrates' Court became the most famous magistrates' court in England in the latter part of its 266-year existence, on the specialisation of the Old Bailey to a Crown Court. It occupied various buildings on Bow Street in Central London immediately north-west of Covent Garden. Its modern-day equivalent is a set of four courts: Westminster Magistrates' Court, Camberwell Green Magistrates Court, Highbury Corner Magistrates' Court and City of London Magistrates' Court.

History

Predecessors were in each of the four counties in which London stood, such as the Middlesex Sessions House and its main predecessor, the Old Bailey which outlived both but saw its role upgraded.

The first court at Bow Street was established in 1740,[1] when Colonel Sir Thomas de Veil, a Westminster justice, sat as a magistrate in his home at Number 4. De Veil was succeeded by novelist and playwright Henry Fielding in 1747. He was appointed a magistrate for the City of Westminster in 1748, at a time when the problem of gin consumption and resultant crime was at its height. There were eight licensed premises in the street and Fielding reported that every fourth house in Covent Garden was a gin shop. In 1749, as a response to the call to find an effective means to tackle the increasing crime and disorder, Fielding brought together eight reliable constables, known as "Mr Fielding's People",[1] who soon gained a reputation for honesty and efficiency in their pursuit of criminals. The constables came to be known as the Bow Street Runners. Fielding's blind half-brother, Sir John Fielding (known as the "Blind Beak of Bow Street"), succeeded his brother as magistrate in 1754 and refined the patrol into the first truly effective police force for the capital.[2] The early 19th century saw a dramatic increase in number and scope of the police based at Bow Street with the 1805 formation of the Bow Street Horse Patrole, which covered to the edge of London and was the first uniformed police unit in Britain, and in 1821 the Dismounted Horse Patrole which covered suburban areas.

When the Metropolitan Police Service was established in 1829, a station house was sited at numbers 25 and 27. In 1876 the Duke of Bedford let a new site on the eastern side of Bow Street to the Commissioners of HM Works and Public Buildings for an annual rent of £100. Work began in 1878 and was completed in 1881—the date of 1879 in the stonework above the door of the present building is the date on which it had been hoped that work would finish.[2][3]

In 1878 gazetteer Walter Thornbury published that the establishment, still called generally a Magistrates' House, consisted of "three magistrates, each attending two days in a week".[4] He added:

The chief magistrate has a large addition to his salary, in lieu of the fees taken at the office, which were formerly appropriated to his emolument, but are now carried to the public account. He also has £500 a year (equivalent to £42,449 in 2015) for the superintendence of the horse patrol. All the magistrates belonging to this office are in the Commission of the Peace for the Counties of Middlesex, Surrey, Kent, and Essex.[4]

Disbandment

Reasons

- During this time, following statute by Parliament, magistrates have gradually transitioned towards sending a vast amount of work, alleged either way offences, to jury system trial, i.e. at the Crown Court ('committal') having considered representations and whether the circumstances would make it of "serious character", "the punishment which a magistrates’ court would have power to inflict for it would be adequate"; and "any other circumstances which appear to the court to make" one way more suitable than the other.[5]

- The immediate location was in Georgian England seen as of logical convenience to the scene of crimes and defendants. Marked improvement in cheap public transport since the 18th century, enabled rival cross-Inner London courts to spread to both sides of the river. The Covent Garden district had seen commercialisation and a resultant loss in population, enabling better use to be put to a site which faced the front entrance to the Royal Opera House.

Closure

In its later years, the court housed the office of the Senior District Judge (Magistrates' Courts), who heard high-profile matters, such as extradition cases or those involving eminent public figures.

In 2004, the court was put up for sale by its joint owners, the Greater London Magistrates' Courts Authority and the Metropolitan Police Authority; the site facing the Royal Opera House was bought by property developer Gerry Barrett for the stated purpose to convert it to a boutique hotel in July 2005,[2] and the court closed its doors for the last time on 14 July 2006; its remaining cases moved to Horseferry Road Magistrates' Court[6] which itself closed and in general terms moved to the old Marylebone Court House and renamed to Westminster Magistrates' Court. The conversion into a hotel never materialized and it was sold to Austrian developers in 2008 who intend to retain the prison cells and establish a World Police Museum.[7] Work finally started on site in April 2015, following a long procurement process and discussions with Westminster Borough Council regarding planning permission and design approval.[8]

The final case was that of Jason John Handy, a 33-year-old alcoholic-vagrant who was accused of breaching his anti-social behaviour order. He was given a one-month conditional discharge. Ironically, this was an illegal sentence as conditional discharges are not available for ASBO breaches. The unfortunate Mr Handy was therefore detained to be re-sentenced by another court. Other cases on the last day included beggars, shoplifters, illegal minicab drivers and a terrorist hearing—the first of its kind—in which a terror suspect was accused of breaching his control order. The final day was heavily attended by members of the press and some became a little carried away by the slightly festive atmosphere and wrongly reported that a defendant by the name of "Mr Bunbury", who did not attend court, was in fact fictitious: the case was an elaborate joke on the part of the court and a completely unsuspecting solicitor, Sean Caulfield. (Mr Bunbury is a character in a work by Oscar Wilde, a previous defendant at Bow Street Magistrates' Court.)

Famous defendants

Many famous accused people have passed through Bow Street, often before committal (whether voluntary or in view of the circumstances) to be tried in the "Old Bailey" (Central Criminal Court) or other Crown Courts, or when being held on extradition or terrorism charges. These include:

- Giacomo Casanova

- Roger Casement

- Dr Crippen

- Abu Hamza al-Masri

- William Joyce

- the Kray twins

- Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst

- General Pinochet

- John Cyril Porte

- Oscar Wilde

External links

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bow Street Magistrates' Court. |

- Battle of Bow Street

- Bow Street

- Bow Street Runners

- Royal Courts of Justice

- Central Criminal Court

- City of Westminster Magistrates' Court

References

- 1 2 Jerry White (2007) London in the 19th Century, Vintage, p383

- 1 2 3 The Times, 31 July 2005, "Bow Street hits the end of the road": http://www.timesonline.co.uk/newspaper/0,,176-1714810,00.html

- ↑ BBC News, 11 July 2006, "Judge laments Bow Street closure": http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/london/5167606.stm

- 1 2 Walter Thornbury (1878). "Covent Garden : Part 3 of 3". Old and New London: Volume 3. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ↑ s.19 Magistrates Court Act 1980

- ↑ BBC News, 12 July 2006, "Bow Street bows out": http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/5169614.stm

- ↑ World Architecture News, 3 June 2011, "Neri & Hu to redevelop Bow Street Magistrates Court in Covent Garden, London": http://www.worldarchitecturenews.com/index.php?fuseaction=wanappln.projectview&upload_id=16793

- ↑ Rise Management Consulting news, 1st December 2014, "RISE APPOINTED AS CONSTRUCTION MANAGER FOR THE CONVERSION OF BOW STREET MAGISTRATES COURT INTO A LUXURY BOUTIQUE HOTEL" : "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 May 2015. Retrieved 2015-05-05.

Coordinates: 51°30′49″N 0°07′21″W / 51.51361°N 0.12250°W