Borexino

|

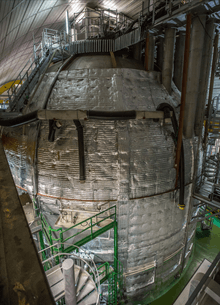

Borexino from the North side of LNGS's underground Hall C in September 2015. It is shown close to being completely wrapped in thermal insulation (seen as a silvery wrapping) as an additional effort to further improve its already unprecedented radiopurity levels. | |

| Detector characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Location | Laboratori Nazionali del Gran Sasso |

| Start of data-taking | 2007 |

| Detection technique | Liquid scintillator (PC+PPO) |

| Height | 16.9 m |

| Width | 18 m |

| Active mass(volume) |

278 tonnes (315 m3) ~100 tonnes fiducial |

Borexino is a particle physics experiment to study low energy (sub-MeV) solar neutrinos. The name Borexino is the Italian diminutive of BOREX (Boron solar neutrino experiment, the original experimental proposal with a different scintillator).[1] The experiment is located at the Laboratori Nazionali del Gran Sasso near the town of L'Aquila, Italy, and is supported by an international collaboration with researchers from Italy, the United States, Germany, France, Poland and Russia.[2] The experiment is funded by multiple national agencies including the INFN (National Institute for Nuclear Physics) and the NSF (National Science Foundation).

The detector is a high-purity liquid scintillator calorimeter. It is placed within a stainless steel sphere which holds the signal detectors (photo-multiplier tubes or PMTs) and is shielded by a water tank to protect it against external radiation and tag incoming cosmic muons that manage to penetrate the overburden of the mountain above. The primary aim of the experiment is to make a precise measurement of the beryllium-7 neutrino flux from the sun and compare it to the Standard solar model predictions. This will allow scientists to further understand the nuclear fusion processes taking place at the core of the Sun and will also help determine properties of neutrino oscillations, including the MSW effect. Other goals of the experiment are to detect boron-8, pp, pep and CNO solar neutrinos as well as anti-neutrinos from the Earth and nuclear power plants. The project may also be able to detect neutrinos from supernovae within our galaxy. Searches for rare processes and potential unknown particles are also underway. The SOX project will study the possible existence of sterile neutrinos or other anomalous effects in neutrino oscillations at short ranges. Borexino is a member of the Supernova Early Warning System.[3]

Results

As of May 2007, the Borexino detector started taking data.[4] The project first detected solar neutrinos in August 2007. This detection occurred in real-time.[5][6] The data analysis was further extended in 2008.[7]

In 2010, geoneutrinos from Earth's interior have been observed for the first time. These are anti-neutrinos produced in radioactive decays of uranium, thorium, potassium, and rubidium, although only the anti-neutrinos emitted in the 238U/232Th chains are visible because of the Inverse Beta Decay (IBD) reaction channel Borexino is sensitive to.[8][9] Additionally, a multi-source detector calibration campaign took place,[10] where several radioactive sources were inserted in the detector to study its response to known signals which are close to the expected ones to be studied.

In 2011, the experiment published a precision measurement of the beryllium-7 neutrino flux,[11][12] as well as the first evidence for the pep solar neutrinos.[13][14]

In 2012, they published the results of measurements of the speed of CERN Neutrinos to Gran Sasso. The results were consistent with the speed of light.[15] See measurements of neutrino speed. An extensive scintillator purification campaign was also performed, achieving the successful goal of further reducing the residual background radioactivity levels to unprecedented low amounts (up to 15 orders of magnitude under natural background radioactivity levels).

In 2013, they set a limit on sterile neutrino parameters.[16] They also extracted a signal of geoneutrinos,[17] which gives insight into radioactive element activity in the earth's crust,[18] a hitherto unclear field.[19]

In 2014, they published an analysis of the proton–proton fusion activity in the solar core, finding solar activity has been consistently stable on a 105-year scale.[20][21]

In 2015, an updated spectral analysis of geoneutrinos was presented,[22] and the world best limit on the electric charge non-conservation (via e−→γ+ν decay) was set.[23] Additionally, a versatile Temperature Management and Monitoring System was installed in several phases throughout 2015. It consists of the multi-sensor Latitudinal Temperature Probe System (LTPS), whose testing and first-phase installation occurred in late 2014; and the Thermal Insulation System (TIS), that minimized the thermal influence of the exterior environment on the interior fluids through the extensive insulation of the experiment's external walls.

SOX project

The SOX experiment[24] aims at the complete confirmation or at a clear disproof of the so-called neutrino anomalies, a set of circumstantial evidences of electron neutrino disappearance observed at LSND, MiniBoone, with nuclear reactors and with solar neutrino Gallium detectors (GALLEX/GNO, SAGE). If successful, SOX will demonstrate the existence of sterile neutrino components and will open a brand new era in fundamental particle physics and cosmology. A solid signal would mean the discovery of the first particles beyond the Standard Electroweak Model and would have profound implications in our understanding of the Universe and of fundamental particle physics. In case of a negative result, it is able to close a long standing debate about the reality of the neutrino anomalies, would probe the existence of new physics in low energy neutrino interactions, would provide a measurement of neutrino magnetic moment, Weinberg angle and other basic physical parameters; and would yield a superb energy calibration for Borexino which will be very beneficial for future high-precision solar neutrino measurements.

SOX will use a powerful (~150 kCi) and innovative antineutrino generator made of Ce-144/Pr-144, and possibly a later Cr-51 neutrino generator, which would require a much shorter data-taking campaign. These generators will be located at short distance (8.5 m) from the Borexino detector -under it, in fact: in a pit built ex-profeso before the detector was erected, with the idea it could be used for the insertion of such radioactive sources- and will yield tens of thousands of clean neutrino interactions in the internal volume of the Borexino detector. The experiment is expected to start in 2017 and will take data for about two years.

References

- ↑ Georg G. Raffelt (1996). "BOREXINO". Stars As Laboratories for Fundamental Physics: The Astrophysics of Neutrinos, Axions, and Other Weakly Interacting Particles. University of Chicago Press. pp. 393–394. ISBN 0226702723.

- ↑ "Borexino Experiment". Borexino Official Website. Gran Sasso. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- ↑ Borexino Collaboration (2008). "The Borexino detector at the Laboratori Nazionali del Gran Sasso". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A. 600 (3): 568–593. arXiv:0806.2400

. Bibcode:2009NIMPA.600..568B. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2008.11.076.

. Bibcode:2009NIMPA.600..568B. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2008.11.076. - ↑ "The Borexino experiment at Gran Sasso begins the data taking". Laboratori Nazionali del Gran Sasso press release. 29 May 2007.

- ↑ Emiliano Feresin (2007). "Low-energy neutrinos spotted". Nature news. doi:10.1038/news070820-5.

- ↑ Borexino Collaboration (2007). "First real time detection of 7Be solar neutrinos by Borexino". Physics Letters B. 658 (4): 101–108. arXiv:0708.2251

. Bibcode:2008PhLB..658..101B. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2007.09.054.

. Bibcode:2008PhLB..658..101B. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2007.09.054. - ↑ Borexino Collaboration (2008). "Direct Measurement of the Be7 Solar Neutrino Flux with 192 Days of Borexino Data". Physical Review Letters. 101 (9): 091302. arXiv:0805.3843

. Bibcode:2008PhRvL.101i1302A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.091302.

. Bibcode:2008PhRvL.101i1302A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.091302. - ↑ "A first look at the Earth interior from the Gran Sasso underground laboratory". INFN press release. 11 March 2010.

- ↑ Borexino Collaboration (2010). "Observation of geo-neutrinos". Physics Letters B. 687 (4–5): 299–304. arXiv:1003.0284

. Bibcode:2010PhLB..687..299B. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2010.03.051.

. Bibcode:2010PhLB..687..299B. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2010.03.051. - ↑ Back, H.; Bellini, G.; Benziger, J.; Bick, D.; Bonfini, G.; Bravo, D.; Avanzini, M. Buizza; Caccianiga, B.; Cadonati, L. (2012-01-01). "Borexino calibrations: hardware, methods, and results". Journal of Instrumentation. 7 (10): P10018. doi:10.1088/1748-0221/7/10/P10018. ISSN 1748-0221.

- ↑ "Precision measurement of the beryllium solar neutrino flux and its day/night asymmetry, and independent validation of the LMA-MSW oscillation solution using Borexino-only data.". Borexino Collaboration press release. 11 April 2011.

- ↑ Borexino Collaboration (2011). "Precision Measurement of the Be7 Solar Neutrino Interaction Rate in Borexino". Physical Review Letters. 107 (14): 141302. arXiv:1104.1816

. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.107n1302B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.141302.

. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.107n1302B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.141302. - ↑ "Borexino Collaboration succeeds in spotting pep neutrinos emitted from the sun". PhysOrg.com. 9 February 2012.

- ↑ Borexino Collaboration (2011). "First Evidence of pep Solar Neutrinos by Direct Detection in Borexino". Physical Review Letters. 108 (5): 051302. arXiv:1110.3230

. Bibcode:2012PhRvL.108e1302B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.051302.

. Bibcode:2012PhRvL.108e1302B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.051302. - ↑ Borexino collaboration (2012). "Measurement of CNGS muon neutrino speed with Borexino". Physics Letters B. 716 (3–5): 401–405. arXiv:1207.6860

. Bibcode:2012PhLB..716..401A. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2012.08.052.

. Bibcode:2012PhLB..716..401A. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2012.08.052. - ↑ Bellini, G.; Benziger, J.; Bick, D.; Bonfini, G.; Bravo, D.; Buizza Avanzini, M.; Caccianiga, B.; Cadonati, L.; Calaprice, F.; Cavalcante, P.; Chavarria, A.; Chepurnov, A.; D’Angelo, D.; Davini, S.; Derbin, A.; Drachnev, I.; Empl, A.; Etenko, A.; Fomenko, K.; Franco, D.; Galbiati, C.; Gazzana, S.; Ghiano, C.; Giammarchi, M.; Göger-Neff, M.; Goretti, A.; Grandi, L.; Hagner, C.; Hungerford, E.; Ianni, Aldo; Ianni, Andrea; Kobychev, V.; Korablev, D.; Korga, G.; Kryn, D.; Laubenstein, M.; Lewke, T.; Litvinovich, E.; Loer, B.; Lombardi, F.; Lombardi, P.; Ludhova, L.; Lukyanchenko, G.; Machulin, I.; Manecki, S.; Maneschg, W.; Manuzio, G.; Meindl, Q.; Meroni, E.; Miramonti, L.; Misiaszek, M.; Mosteiro, P.; Muratova, V.; Oberauer, L.; Obolensky, M.; Ortica, F.; Otis, K.; Pallavicini, M.; Papp, L.; Perasso, L.; Perasso, S.; Pocar, A.; Ranucci, G.; Razeto, A.; Re, A.; Romani, A.; Rossi, N.; Saldanha, R.; Salvo, C.; Schönert, S.; Simgen, H.; Skorokhvatov, M.; Smirnov, O.; Sotnikov, A.; Sukhotin, S.; Suvorov, Y.; Tartaglia, R.; Testera, G.; Vignaud, D.; Vogelaar, R. B.; von Feilitzsch, F.; Winter, J.; Wojcik, M.; Wright, A.; Wurm, M.; Xu, J.; Zaimidoroga, O.; Zavatarelli, S.; Zuzel, G. "New limits on heavy sterile neutrino mixing in ^{8}B decay obtained with the Borexino detector". Physical Review D. 88 (7). arXiv:1311.5347

. Bibcode:2013PhRvD..88g2010B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.88.072010.

. Bibcode:2013PhRvD..88g2010B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.88.072010. - ↑ Borexino Collaboration (15 April 2013). "Measurement of geo-neutrinos from 1353 days of Borexino". Phys. Lett. B. arXiv:1303.2571

. Bibcode:2013PhLB..722..295B. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2013.04.030.

. Bibcode:2013PhLB..722..295B. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2013.04.030. - ↑ "Borexino has new results on geoneutrinos". CERN COURIER. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ http://www.nature.com/articles/srep33034?WT.feed_name=subjects_physical-sciences

- ↑ Borexino Collaboration (27 August 2014). "Neutrinos from the primary proton–proton fusion process in the Sun". Nature. 512 (7515): 383–386. Bibcode:2014Natur.512..383B. doi:10.1038/nature13702. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ "Borexino measures the Sun's energy in real time". CERN COURIER. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ Borexino Collaboration (7 August 2015). "Spectroscopy of geoneutrinos from 2056 days of Borexino data". Phys. Lett. D. 92 (3): 031101. arXiv:1506.04610

. Bibcode:2015PhRvD..92c1101A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.92.031101.

. Bibcode:2015PhRvD..92c1101A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.92.031101. - ↑ Agostini, M.; et al. (Borexino Coll.) (2015). "Test of Electric Charge Conservation with Borexino". Physical Review Letters. 115 (23): 231802. arXiv:1509.01223

. Bibcode:2015PhRvL.115w1802A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.231802.

. Bibcode:2015PhRvL.115w1802A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.231802. - ↑ Caminata, Alessio. "The SOX project". web.ge.infn.it. Retrieved 2016-04-22.

External links

Coordinates: 42°28′N 13°34′E / 42.46°N 13.57°E