Police

A police force is a constituted body of persons empowered by the state to enforce the law, protect property, and limit civil disorder.[1] Their powers include the legitimized use of force. The term is most commonly associated with police services of a sovereign state that are authorized to exercise the police power of that state within a defined legal or territorial area of responsibility. Police forces are often defined as being separate from military or other organizations involved in the defense of the state against foreign aggressors; however, gendarmerie are military units charged with civil policing.

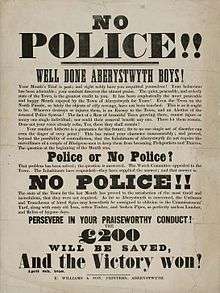

Law enforcement, however, constitutes only part of policing activity.[2] Policing has included an array of activities in different situations, but the predominant ones are concerned with the preservation of order.[3] In some societies, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, these developed within the context of maintaining the class system and the protection of private property.[4] Many police forces suffer from police corruption to a greater or lesser degree. The police force is usually a public sector service, meaning they are paid through taxes.

Alternative names for police force include constabulary, gendarmerie, police department, police service, crime prevention, protective services, law enforcement agency, civil guard or civic guard. Members may be referred to as police officers, troopers, sheriffs, constables, rangers, peace officers or civic/civil guards. In colloquial English,

As police are often interacting with individuals, slang terms are numerous. Many slang terms for police officers are decades or centuries old with lost etymology. One of the oldest, "cop," has largely lost its slang connotations and become a common colloquial term used both by the public and police officers to refer to their profession.[5]

Etymology

First attested in English in the early 15th century, initially in a range of senses encompassing '(public) policy; state; public order', the word police comes from Middle French police ('public order, administration, government'),[6] in turn from Latin politia,[7] which is the Latinisation of the Greek πολιτεία (politeia), "citizenship, administration, civil polity".[8] This is derived from πόλις (polis), "city".[9]

History

Ancient policing

Law enforcement in ancient China was carried out by "prefects" for thousands of years since it developed in both the Chu and Jin kingdoms of the Spring and Autumn period. In Jin, dozens of prefects were spread across the state, each having limited authority and employment period. They were appointed by local magistrates, who reported to higher authorities such as governors, who in turn were appointed by the emperor, and they oversaw the civil administration of their "prefecture", or jurisdiction. Under each prefect were "subprefects" who helped collectively with law enforcement in the area. Some prefects were responsible for handling investigations, much like modern police detectives. Prefects could also be women.[10] The concept of the "prefecture system" spread to other cultures such as Korea and Japan.

In ancient Greece, publicly owned slaves were used by magistrates as police. In Athens, a group of 300 Scythian slaves (the ῥαβδοῦχοι, "rod-bearers") was used to guard public meetings to keep order and for crowd control, and also assisted with dealing with criminals, handling prisoners, and making arrests. Other duties associated with modern policing, such as investigating crimes, were left to the citizens themselves.[11]

In the Roman empire, the army, rather than a dedicated police organization, provided security. Local watchmen were hired by cities to provide some extra security. Magistrates such as procurators fiscal and quaestors investigated crimes. There was no concept of public prosecution, so victims of crime or their families had to organize and manage the prosecution themselves.

Under the reign of Augustus, when the capital had grown to almost one million inhabitants, 14 wards were created; the wards were protected by seven squads of 1,000 men called "vigiles", who acted as firemen and nightwatchmen. Their duties included apprehending thieves and robbers and capturing runaway slaves. The vigiles were supported by the Urban Cohorts who acted as a heavy-duty anti-riot force and even the Praetorian Guard if necessary.

Medieval policing

In medieval Spain, Santa Hermandades, or "(holy) brotherhoods", peacekeeping associations of armed individuals, were a characteristic of municipal life, especially in Castile. As medieval Spanish kings often could not offer adequate protection, protective municipal leagues began to emerge in the twelfth century against banditry and other rural criminals, and against the lawless nobility or to support one or another claimant to a crown.

These organizations were intended to be temporary, but became a long-standing fixture of Spain. The first recorded case of the formation of an hermandad occurred when the towns and the peasantry of the north united to police the pilgrim road to Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, and protect the pilgrims against robber knights.

Throughout the Middle Ages such alliances were frequently formed by combinations of towns to protect the roads connecting them, and were occasionally extended to political purposes. Among the most powerful was the league of North Castilian and Basque ports, the Hermandad de las marismas: Toledo, Talavera, and Villarreal.

As one of their first acts after end of the War of the Castilian Succession in 1479, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile established the centrally-organized and efficient Holy Brotherhood as a national police force. They adapted an existing brotherhood to the purpose of a general police acting under officials appointed by themselves, and endowed with great powers of summary jurisdiction even in capital cases. The original brotherhoods continued to serve as modest local police-units until their final suppression in 1835.

The Vehmic courts of Germany provided some policing in the absence of strong state institutions.

In France during the Middle Ages, there were two Great Officers of the Crown of France with police responsibilities: The Marshal of France and the Constable of France. The military policing responsibilities of the Marshal of France were delegated to the Marshal's provost, whose force was known as the Marshalcy because its authority ultimately derived from the Marshal. The marshalcy dates back to the Hundred Years' War, and some historians trace it back to the early 12th century. Another organisation, the Constabulary (French: Connétablie), was under the command of the Constable of France. The constabulary was regularised as a military body in 1337. Under Francis I of France (who reigned 1515–1547), the Maréchaussée was merged with the Constabulary. The resulting force was also known as the Maréchaussée, or, formally, the Constabulary and Marshalcy of France.

The English system of maintaining public order since the Norman conquest was a private system of tithings, led by a constable, which was based on a social obligation for the good conduct of the others; more common was that local lords and nobles were responsible for maintaining order in their lands, and often appointed a constable, sometimes unpaid, to enforce the law. There was also a system investigative "juries".

The Assize of Arms of 1252, which required the appointment of constables to summon men to arms, quell breaches of the peace, and to deliver offenders to the sheriffs or reeves, is cited as one of the earliest creation of the English police.[12] The Statute of Winchester of 1285 is also cited as the primary legislation regulating the policing of the country between the Norman Conquest and the Metropolitan Police Act 1829.[12][13]

From about 1500, private watchmen were funded by private individuals and organisations to carry out police functions. They were later nicknamed 'Charlies', probably after the reigning monarch King Charles II. Thief-takers were also rewarded for catching thieves and returning the stolen property.

The first use of the word police ("Polles") in English comes from the book "The Second Part of the Institutes of the Lawes of England" published in 1642.[14]

Early modern policing

The first centrally organised police force was created by the government of King Louis XIV in 1667 to police the city of Paris, then the largest city in Europe. The royal edict, registered by the Parlement of Paris on March 15, 1667 created the office of lieutenant général de police ("lieutenant general of police"), who was to be the head of the new Paris police force, and defined the task of the police as "ensuring the peace and quiet of the public and of private individuals, purging the city of what may cause disturbances, procuring abundance, and having each and everyone live according to their station and their duties".

This office was first held by Gabriel Nicolas de la Reynie, who had 44 commissaires de police (police commissioners) under his authority. In 1709, these commissioners were assisted by inspecteurs de police (police inspectors). The city of Paris was divided into 16 districts policed by the commissaires, each assigned to a particular district and assisted by a growing bureaucracy. The scheme of the Paris police force was extended to the rest of France by a royal edict of October 1699, resulting in the creation of lieutenants general of police in all large French cities and towns.

After the French Revolution, Napoléon I reorganized the police in Paris and other cities with more than 5,000 inhabitants on February 17, 1800 as the Prefecture of Police. On March 12, 1829, a government decree created the first uniformed police in France, known as sergents de ville ("city sergeants"), which the Paris Prefecture of Police's website claims were the first uniformed policemen in the world.[15]

In 1737, George II began paying some London and Middlesex watchmen with tax monies, beginning the shift to government control. In 1749 Henry Fielding began organizing a force of quasi-professional constables known as the Bow Street Runners. The Macdaniel affair added further impetus for a publicly salaried police force that did not depend on rewards. Nonetheless, In 1828, there were privately financed police units in no fewer than 45 parishes within a 10-mile radius of London.

The word "police" was borrowed from French into the English language in the 18th century, but for a long time it applied only to French and continental European police forces. The word, and the concept of police itself, were "disliked as a symbol of foreign oppression" (according to Britannica 1911). Before the 19th century, the first use of the word "police" recorded in government documents in the United Kingdom was the appointment of Commissioners of Police for Scotland in 1714 and the creation of the Marine Police in 1798.

Policing in London

In 1797, Patrick Colquhoun was able to persuade the West Indies merchants who operated at the Pool of London on the River Thames, to establish a police force at the docks to prevent rampant theft that was causing annual estimated losses of £500,000 worth of cargo.[16] The idea of a police, as it then existed in France, was considered as a potentially undesirable foreign import. In building the case for the police in the face of England's firm anti-police sentiment, Colquhoun framed the political rationale on economic indicators to show that a police dedicated to crime prevention was "perfectly congenial to the principle of the British constitution." Moreover, he went so far as to praise the French system, which had reached "the greatest degree of perfection" in his estimation.[17]

With the initial investment of £4,200, the new trial force of the Thames River Police began with about 50 men charged with policing 33,000 workers in the river trades, of whom Colquhoun claimed 11,000 were known criminals and "on the game." The force was a success after its first year, and his men had "established their worth by saving £122,000 worth of cargo and by the rescuing of several lives." Word of this success spread quickly, and the government passed the Marine Police Bill on 28 July 1800, transforming it from a private to public police agency; now the oldest police force in the world. Colquhoun published a book on the experiment, The Commerce and Policing of the River Thames. It found receptive audiences far outside London, and inspired similar forces in other cities, notably, New York City, Dublin, and Sydney.[16]

Colquhoun's utilitarian approach to the problem – using a cost-benefit argument to obtain support from businesses standing to benefit – allowed him to achieve what Henry and John Fielding failed for their Bow Street detectives. Unlike the stipendiary system at Bow Street, the river police were full-time, salaried officers prohibited from taking private fees.[18] His other contribution was the concept of preventive policing; his police were to act as a highly visible deterrent to crime by their permanent presence on the Thames.[17] Colquhoun's innovations were a critical development leading up to Robert Peel's "new" police three decades later.[19]

Meanwhile, the authorities in Glasgow, Scotland successfully petitioned the government to pass the Glasgow Police Act establishing the City of Glasgow Police in 1800. Other Scottish towns soon followed suit and set up their own police forces through acts of parliament.[20] In Ireland, the Irish Constabulary Act of 1822 marked the beginning of the Royal Irish Constabulary. The Act established a force in each barony with chief constables and inspectors general under the control of the civil administration at Dublin Castle. By 1841 this force numbered over 8,600 men.

Metropolitan police force

London was fast reaching a size unprecedented in world history, due to the onset of the Industrial Revolution.[21] It became clear that the locally maintained system of volunteer constables and "watchmen" was ineffective, both in detecting and preventing crime. A parliamentary committee was appointed to investigate the system of policing in London. Upon Sir Robert Peel being appointed as Home Secretary in 1822, he established a second and more effective committee, and acted upon its findings.

Royal assent to the Metropolitan Police Act 1829 was given[22] and the Metropolitan Police Service was established on September 29, 1829 in London as the first modern and professional police force in the world.[23][24][25]

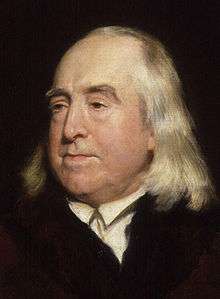

Peel, widely regarded as the father of modern policing,[26] was heavily influenced by the social and legal philosophy of Jeremy Bentham, who called for a strong and centralized, but politically neutral, police force for the maintenance of social order, for the protection of people from crime and to act as a visible deterrent to urban crime and disorder.[27] Peel decided to standardise the police force as an official paid profession, to organise it in a civilian fashion, and to make it answerable to the public.[28]

Due to public fears concerning the deployment of the military in domestic matters, Peel organised the force along civilian lines, rather than paramilitary. To appear neutral, the uniform was deliberately manufactured in blue, rather than red which was then a military colour, along with the officers being armed only with a wooden truncheon and a rattle to signal the need for assistance. Along with this, police ranks did not include military titles, with the exception of Sergeant.[29]

To distance the new police force from the initial public view of it as a new tool of government repression, Peel publicised the so-called Peelian principles, which set down basic guidelines for ethical policing:

- Every police officer should be issued an warrant card with a unique identification number to assure accountability for his actions.

- Whether the police are effective is not measured on the number of arrests but on the lack of crime.

- Above all else, an effective authority figure knows trust and accountability are paramount. Hence, Peel's most often quoted principle that "The police are the public and the public are the police."

The 1829 Metropolitan Police Act created a modern police force by limiting the purview of the force and its powers, and envisioning it as merely an organ of the judicial system. Their job was apolitical; to maintain the peace and apprehend criminals for the courts to process according to the law.[30] This was very different to the "continental model" of the police force that had been developed in France, where the police force worked within the parameters of the absolutist state as an extension of the authority of the monarch and functioned as part of the governing state.

In 1863, the Metropolitan Police were issued with the distinctive custodian helmet, and in 1884 they switched to the use of whistles that could be heard from much further away.[31] The Metropolitan Police became a model for the police forces in most countries, such as the United States, and most of the British Empire. Bobbies can still be found in many parts of the Commonwealth of Nations.[32]

Other countries

Australia

In Australia the first police force having centralised command as well as jurisdiction over an entire colony was the South Australia Police, formed in 1838 under Henry Inman.

However, whilst the New South Wales Police Force was established in 1862, it was made up from a large number of policing and military units operating within the then Colony of New South Wales and traces its links back to the Royal Marines. The passing of the Police Regulation Act of 1862 essentially tightly regulated and centralised all of the police forces operating throughout the Colony of New South Wales.

The New South Wales Police Force remains the largest police force in Australia in terms of personnel and physical resources. It is also the only police force that requires its recruits to undertake university studies at the recruit level and has the recruit pay for their own education.

Brazil

In 1566, the first police investigator of Rio de Janeiro was recruited. By the 17th century, most captaincies already had local units with law enforcement functions. On July 9, 1775 a Cavalry Regiment was created in the state of Minas Gerais for maintaining law and order. In 1808, the Portuguese royal family relocated to Brazil, because of the French invasion of Portugal. King João VI established the "Intendência Geral de Polícia" (General Police Intendancy) for investigations. He also created a Royal Police Guard for Rio de Janeiro in 1809. In 1831, after independence, each province started organizing its local "military police", with order maintenance tasks. The Federal Railroad Police was created in 1852, Federal Highway Police, was established in 1928, and Federal Police in 1967.

Canada

In Canada, the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary was founded in 1729, making it the first police force in present-day Canada. It was followed in 1834 by the Toronto Police, and in 1838 by police forces in Montreal and Quebec City. A national force, the Dominion Police, was founded in 1868. Initially the Dominion Police provided security for parliament, but its responsibilities quickly grew. The famous Royal Northwest Mounted Police was founded in 1873. The merger of these two police forces in 1920 formed the world-famous Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

Lebanon

In Lebanon, modern police were established in 1861, with creation of the Gendarmerie.[33]

India

In India, the police is under the control of respective States and union territories and is known to be under State Police Services (SPS). The candidates selected for the SPS are usually posted as Deputy Superintendent of Police or Assistant Commissioner of Police once their probationary period ends. On prescribed satisfactory service in the SPS, the officers are nominated to the Indian Police Service.[34] The service color is usually dark blue and red, while the uniform color is Khaki.[35]

United States

In British North America, policing was initially provided by local elected officials. For instance, the New York Sheriff's Office was founded in 1626, and the Albany County Sheriff's Department in the 1660s. In the colonial period, policing was provided by elected sheriffs and local militias.

In 1789 the U.S. Marshals Service was established, followed by other federal services such as the U.S. Parks Police (1791)[36] and U.S. Mint Police (1792).[37] The first city police services were established in Philadelphia in 1751,[38] Richmond, Virginia in 1807,[39] Boston in 1838,[40] and New York in 1845.[41] The U.S. Secret Service was founded in 1865 and was for some time the main investigative body for the federal government.[42]

In the American Old West, policing was often of very poor quality. The Army often provided some policing alongside poorly resourced sheriffs and temporarily organized posses. Public organizations were supplemented by private contractors, notably the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, which was hired by individuals, businessmen, local governments and the federal government. At its height, the Pinkerton Agency's numbers exceeded those of the United States Army.

In recent years, in addition to federal, state, and local forces, some special districts have been formed to provide extra police protection in designated areas. These districts may be known as neighborhood improvement districts, crime prevention districts, or security districts.[43]

In 2005, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that police do not have a constitutional duty to protect a person from harm.[44]

Development of theory

Michel Foucault claims that the contemporary concept of police as a paid and funded functionary of the state was developed by German and French legal scholars and practitioners in Public administration and Statistics in the 17th and early 18th centuries, most notably with Nicolas Delamare's Traité de la Police ("Treatise on the Police"), first published in 1705. The German Polizeiwissenschaft (Science of Police) first theorized by Philipp von Hörnigk a 17th-century Austrian Political economist and civil servant and much more famously by Johann Heinrich Gottlob Justi who produced an important theoretical work known as Cameral science on the formulation of police.[45] Foucault cites Magdalene Humpert author of Bibliographie der Kameralwissenschaften (1937) in which the author makes note of a substantial bibliography was produced of over 4000 pieces of the practice of Polizeiwissenschaft however, this maybe a mistranslation of Foucault's own work the actual source of Magdalene Humpert states over 14,000 items were produced from the 16th century dates ranging from 1520-1850.[46][47]

As conceptualized by the Polizeiwissenschaft,according to Foucault the police had an administrative,economic and social duty ("procuring abundance"). It was in charge of demographic concerns and needed to be incorporated within the western political philosophy system of raison d'état and therefore giving the superficial appearance of empowering the population (and unwittingly supervising the population), which, according to mercantilist theory, was to be the main strength of the state. Thus, its functions largely overreached simple law enforcement activities and included public health concerns, urban planning (which was important because of the miasma theory of disease; thus, cemeteries were moved out of town, etc.), and surveillance of prices.[48]

The concept of preventive policing, or policing to deter crime from taking place, gained influence in the late 18th century. Police Magistrate John Fielding, head of the Bow Street Runners, argued that "...it is much better to prevent even one man from being a rogue than apprehending and bringing forty to justice."[49]

The Utilitarian philosopher, Jeremy Bentham, promoted the views of Italian Marquis Cesare Beccaria, and disseminated a translated version of "Essay on Crime in Punishment". Bentham espoused the guiding principle of "the greatest good for the greatest number:

It is better to prevent crimes than to punish them. This is the chief aim of every good system of legislation, which is the art of leading men to the greatest possible happiness or to the least possible misery, according to calculation of all the goods and evils of life.[49]

Patrick Colquhoun's influential work, A Treatise on the Police of the Metropolis (1797) was heavily influenced by Benthamite thought. Colquhoun's Thames River Police was founded on these principles, and in contrast to the Bow Street Runners, acted as a deterrent by their continual presence on the riverfront, in addition to being able to intervene if they spotted a crime in progress.[50]

Edwin Chadwick's 1829 article, "Preventive police" in the London Review,[51] argued that prevention ought to be the primary concern of a police body, which was not the case in practice. The reason, argued Chadwick, was that "A preventive police would act more immediately by placing difficulties in obtaining the objects of temptation." In contrast to a deterrent of punishment, a preventive police force would deter criminality by making crime cost-ineffective - "crime doesn't pay". In the second draft of his 1829 Police Act, the "object" of the new Metropolitan Police, was changed by Robert Peel to the "principal object," which was the "prevention of crime."[52] Later historians would attribute the perception of England's "appearance of orderliness and love of public order" to the preventive principle entrenched in Peel's police system.[53]

Development of modern police forces around the world was contemporary to the formation of the state, later defined by sociologist Max Weber as achieving a "monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force" and which was primarily exercised by the police and the military. Marxist theory situates the development of the modern state as part of the rise of capitalism, in which the police are one component of the bourgeoisie's repressive apparatus for subjugating the working class.

Personnel and organization

Police forces include both preventive (uniformed) police and detectives. Terminology varies from country to country. Police functions include protecting life and property, enforcing criminal law, criminal investigations, regulating traffic, crowd control, and other public safety duties.

Uniformed police

Preventive Police, also called Uniform Branch, Uniformed Police, Uniform Division, Administrative Police, Order Police, or Patrol, designates the police that patrol and respond to emergencies and other incidents, as opposed to detective services. As the name "uniformed" suggests, they wear uniforms and perform functions that require an immediate recognition of an officer's legal authority, such as traffic control, stopping and detaining motorists, and more active crime response and prevention.

Preventive police almost always make up the bulk of a police service's personnel. In Australia and Britain, patrol personnel are also known as "general duties" officers.[54] Atypically, Brazil's preventive police are known as Military Police.[55]

Detectives

Police detectives are responsible for investigations and detective work. Detectives may be called Investigations Police, Judiciary/Judicial Police, and Criminal Police. In the UK, they are often referred to by the name of their department, the Criminal Investigation Department (CID). Detectives typically make up roughly 15%-25% of a police service's personnel.

Detectives, in contrast to uniformed police, typically wear 'business attire' in bureaucratic and investigative functions where a uniformed presence would be either a distraction or intimidating, but a need to establish police authority still exists. "Plainclothes" officers dress in attire consistent with that worn by the general public for purposes of blending in.

In some cases, police are assigned to work "undercover", where they conceal their police identity to investigate crimes, such as organized crime or narcotics crime, that are unsolvable by other means. In some cases this type of policing shares aspects with espionage.

Despite popular conceptions promoted by movies and television, many US police departments prefer not to maintain officers in non-patrol bureaus and divisions beyond a certain period of time, such as in the detective bureau, and instead maintain policies that limit service in such divisions to a specified period of time, after which officers must transfer out or return to patrol duties. This is done in part based upon the perception that the most important and essential police work is accomplished on patrol in which officers become acquainted with their beats, prevent crime by their presence, respond to crimes in progress, manage crises, and practice their skills.

Detectives, by contrast, usually investigate crimes after they have occurred and after patrol officers have responded first to a situation. Investigations often take weeks or months to complete, during which time detectives spend much of their time away from the streets, in interviews and courtrooms, for example. Rotating officers also promotes cross-training in a wider variety of skills, and serves to prevent "cliques" that can contribute to corruption or other unethical behavior.

Auxiliary

Police may also take on auxiliary administrative duties, such as issuing firearms licenses. The extent that police have these functions varies among countries, with police in France, Germany, and other continental European countries handling such tasks to a greater extent than British counterparts.[54]

Specialized units

Specialized preventive and detective groups, or Specialist Investigation Departments exist within many law enforcement organizations either for dealing with particular types of crime, such as traffic law enforcement and crash investigation, homicide, or fraud; or for situations requiring specialized skills, such as underwater search, aviation, explosive device disposal ("bomb squad"), and computer crime.

Most larger jurisdictions also employ specially selected and trained quasi-military units armed with military-grade weapons for the purposes of dealing with particularly violent situations beyond the capability of a patrol officer response, including high-risk warrant service and barricaded suspects. In the United States these units go by a variety of names, but are commonly known as SWAT (Special Weapons And Tactics) teams.

In counterinsurgency-type campaigns, select and specially trained units of police armed and equipped as light infantry have been designated as police field forces who perform paramilitary-type patrols and ambushes whilst retaining their police powers in areas that were highly dangerous.[56]

Because their situational mandate typically focuses on removing innocent bystanders from dangerous people and dangerous situations, not violent resolution, they are often equipped with non-lethal tactical tools like chemical agents, "flashbang" and concussion grenades, and rubber bullets. The London Metropolitan police's Specialist Firearms Command (CO19)[57] is a group of armed police used in dangerous situations including hostage taking, armed robbery/assault and terrorism.

Military police

Military police may refer to:

- a section of the military solely responsible for policing the armed forces (referred to as provosts)

- a section of the military responsible for policing in both the armed forces and in the civilian population (most gendarmeries, such as the French Gendarmerie, the Italian Carabinieri, the Spanish Guardia Civil and the Portuguese Republican National Guard also known as GNR)

- a section of the military solely responsible for policing the civilian population (such as the Romanian Gendarmerie)

- the civilian preventive police of a Brazilian state (Policia Militar)

- a Special Military law enforcement Service, like the Russian Military Police

Religious police

Some Islamic societies have religious police, who enforce the application of Islamic Sharia law. Their authority may include the power to arrest unrelated men and women caught socializing, anyone engaged in homosexual behavior or prostitution; to enforce Islamic dress codes, and store closures during Islamic prayer time.[58][59]

They enforce Muslim dietary laws, prohibit the consumption or sale of alcoholic beverages and pork, and seize banned consumer products and media regarded as un-Islamic, such as CDs/DVDs of various Western musical groups, television shows and film.[58][59] In Saudi Arabia, the Mutaween actively prevent the practice or proselytizing of non-Islamic religions within Saudi Arabia, where they are banned.[58][59]

Varying jurisdictions

Police forces are usually organized and funded by some level of government. The level of government responsible for policing varies from place to place, and may be at the national, regional or local level. In some places there may be multiple police forces operating in the same area, with different ones having jurisdiction according to the type of crime or other circumstances.

For example, in the UK, policing is primarily the responsibility of a regional police force; however specialist units exist at the national level. In the US, there is typically a state police force, but crimes are usually handled by local police forces that usually only cover a few municipalities. National agencies, such as the FBI, only have jurisdiction over federal crimes or those with an interstate component.

In addition to conventional urban or regional police forces, there are other police forces with specialized functions or jurisdiction. In the United States, the federal government has a number of police forces with their own specialized jurisdictions.

Some examples are the Federal Protective Service, which patrols and protects government buildings; the postal police, which protect postal buildings, vehicles and items; the Park Police, which protect national parks, or Amtrak Police which patrol Amtrak stations and trains.

There are also some government agencies that perform police functions in addition to other duties. The U.S. Coast Guard carries out many police functions for boaters.

In major cities, there may be a separate police agency for public transit systems, such as the New York City Port Authority Police or the MTA police, or for major government functions, such as sanitation, or environmental functions.

International policing

The terms international policing, transnational policing, and/or global policing began to be used from the early 1990s onwards to describe forms of policing that transcended the boundaries of the sovereign nation-state (Nadelmann, 1993),[60] (Sheptycki, 1995).[61] These terms refer in variable ways to practices and forms for policing that, in some sense, transcend national borders. This includes a variety of practices, but international police cooperation, criminal intelligence exchange between police agencies working in different nation-states, and police development-aid to weak, failed or failing states are the three types that have received the most scholarly attention.

Historical studies reveal that policing agents have undertaken a variety of cross-border police missions for many years (Deflem, 2002).[62] For example, in the 19th century a number of European policing agencies undertook cross-border surveillance because of concerns about anarchist agitators and other political radicals. A notable example of this was the occasional surveillance by Prussian police of Karl Marx during the years he remained resident in London. The interests of public police agencies in cross-border co-operation in the control of political radicalism and ordinary law crime were primarily initiated in Europe, which eventually led to the establishment of Interpol before the Second World War. There are also many interesting examples of cross-border policing under private auspices and by municipal police forces that date back to the 19th century (Nadelmann, 1993).[60] It has been established that modern policing has transgressed national boundaries from time to time almost from its inception. It is also generally agreed that in the post–Cold War era this type of practice became more significant and frequent (Sheptycki, 2000).[63]

Not a lot of empirical work on the practices of inter/transnational information and intelligence sharing has been undertaken. A notable exception is James Sheptycki's study of police cooperation in the English Channel region (2002),[64] which provides a systematic content analysis of information exchange files and a description of how these transnational information and intelligence exchanges are transformed into police case-work. The study showed that transnational police information sharing was routinized in the cross-Channel region from 1968 on the basis of agreements directly between the police agencies and without any formal agreement between the countries concerned. By 1992, with the signing of the Schengen Treaty, which formalized aspects of police information exchange across the territory of the European Union, there were worries that much, if not all, of this intelligence sharing was opaque, raising questions about the efficacy of the accountability mechanisms governing police information sharing in Europe (Joubert and Bevers, 1996).[65]

Studies of this kind outside of Europe are even rarer, so it is difficult to make generalizations, but one small-scale study that compared transnational police information and intelligence sharing practices at specific cross-border locations in North America and Europe confirmed that low visibility of police information and intelligence sharing was a common feature (Alain, 2001).[66] Intelligence-led policing is now common practice in most advanced countries (Ratcliffe, 2007)[67] and it is likely that police intelligence sharing and information exchange has a common morphology around the world (Ratcliffe, 2007).[67] James Sheptycki has analyzed the effects of the new information technologies on the organization of policing-intelligence and suggests that a number of 'organizational pathologies' have arisen that make the functioning of security-intelligence processes in transnational policing deeply problematic. He argues that transnational police information circuits help to "compose the panic scenes of the security-control society".[68] The paradoxical effect is that, the harder policing agencies work to produce security, the greater are feelings of insecurity.

Police development-aid to weak, failed or failing states is another form of transnational policing that has garnered attention. This form of transnational policing plays an increasingly important role in United Nations peacekeeping and this looks set to grow in the years ahead, especially as the international community seeks to develop the rule of law and reform security institutions in States recovering from conflict (Goldsmith and Sheptycki, 2007)[69] With transnational police development-aid the imbalances of power between donors and recipients are stark and there are questions about the applicability and transportability of policing models between jurisdictions (Hills, 2009).[70]

Perhaps the greatest question regarding the future development of transnational policing is: in whose interest is it? At a more practical level, the question translates into one about how to make transnational policing institutions democratically accountable (Sheptycki, 2004).[71] For example, according to the Global Accountability Report for 2007 (Lloyd, et al. 2007) Interpol had the lowest scores in its category (IGOs), coming in tenth with a score of 22% on overall accountability capabilities (p. 19).[72] As this report points out, and the existing academic literature on transnational policing seems to confirm, this is a secretive area and one not open to civil society involvement.

Equipment

Weapons

In many jurisdictions, police officers carry firearms, primarily handguns, in the normal course of their duties. In the United Kingdom (except Northern Ireland), Iceland, Ireland, Norway, New Zealand,[73] and Malta, with the exception of specialist units, officers do not carry firearms as a matter of course.

Police often have specialist units for handling armed offenders, and similar dangerous situations, and can (depending on local laws), in some extreme circumstances, call on the military (since Military Aid to the Civil Power is a role of many armed forces). Perhaps the most high-profile example of this was, in 1980 the Metropolitan Police handing control of the Iranian Embassy Siege to the Special Air Service.

They can also be armed with non-lethal (more accurately known as "less than lethal" or "less-lethal") weaponry, particularly for riot control. Non-lethal weapons include batons, tear gas, riot control agents, rubber bullets, riot shields, water cannons and electroshock weapons. Police officers often carry handcuffs to restrain suspects. The use of firearms or deadly force is typically a last resort only to be used when necessary to save human life, although some jurisdictions (such as Brazil) allow its use against fleeing felons and escaped convicts. A "shoot-to-kill" policy was recently introduced in South Africa, which allows police to use deadly force against any person who poses a significant threat to them or civilians.[74] With the country having one of the highest rates of violent crime, president Jacob Zuma states that South Africa needs to handle crime differently from other countries.[75]

Communications

Modern police forces make extensive use of radio communications equipment, carried both on the person and installed in vehicles, to co-ordinate their work, share information, and get help quickly. In recent years, vehicle-installed computers have enhanced the ability of police communications, enabling easier dispatching of calls, criminal background checks on persons of interest to be completed in a matter of seconds, and updating officers' daily activity log and other, required reports on a real-time basis. Other common pieces of police equipment include flashlights/torches, whistles, police notebooks and "ticket books" or citations.

Vehicles

Police vehicles are used for detaining, patrolling and transporting. The average police patrol vehicle is a specially modified, four door sedan (saloon in British English). Police vehicles are usually marked with appropriate logos and are equipped with sirens and flashing light bars to aid in making others aware of police presence.

Unmarked vehicles are used primarily for sting operations or apprehending criminals without alerting them to their presence. Some police forces use unmarked or minimally marked cars for traffic law enforcement, since drivers slow down at the sight of marked police vehicles and unmarked vehicles make it easier for officers to catch speeders and traffic violators. This practice is controversial, with for example, New York State banning this practice in 1996 on the grounds that it endangered motorists who might be pulled over by people impersonating police officers.[76]

Motorcycles are also commonly used, particularly in locations that a car may not be able to reach, to control potential public order situations involving meetings of motorcyclists and often in escort duties where motorcycle police officers can quickly clear a path for escorted vehicles. Bicycle patrols are used in some areas because they allow for more open interaction with the public. In addition, their quieter operation can facilitate approaching suspects unawares and can help in pursuing them attempting to escape on foot.

Police forces use an array of specialty vehicles such as helicopters, airplanes, watercraft, mobile command posts, vans, trucks, all-terrain vehicles, motorcycles, and armored vehicles.

Other safety equipment

Police cars may also contain fire extinguishers[77][78] or defibrillators.[79]

Strategies

The advent of the police car, two-way radio, and telephone in the early 20th century transformed policing into a reactive strategy that focused on responding to calls for service.[80] With this transformation, police command and control became more centralized.

In the United States, August Vollmer introduced other reforms, including education requirements for police officers.[81] O.W. Wilson, a student of Vollmer, helped reduce corruption and introduce professionalism in Wichita, Kansas, and later in the Chicago Police Department.[82] Strategies employed by O.W. Wilson included rotating officers from community to community to reduce their vulnerability to corruption, establishing of a non-partisan police board to help govern the police force, a strict merit system for promotions within the department, and an aggressive recruiting drive with higher police salaries to attract professionally qualified officers.[83] During the professionalism era of policing, law enforcement agencies concentrated on dealing with felonies and other serious crime, rather than broader focus on crime prevention.[84]

The Kansas City Preventive Patrol study in the 1970s found this approach to policing to be ineffective. Patrol officers in cars were disconnected from the community, and had insufficient contact and interaction with the community.[85] In the 1980s and 1990s, many law enforcement agencies began to adopt community policing strategies, and others adopted problem-oriented policing.

Broken windows policing was another, related approach introduced in the 1980s by James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling, who suggested that police should pay greater attention to minor "quality of life" offenses and disorderly conduct. This method was first introduced and made popular by New York City Mayor, Rudy Giuliani, in the early 1990s.

The concept behind this method is simple: broken windows, graffiti, and other physical destruction or degradation of property, greatly increases the chances of more criminal activities and destruction of property. When criminals see the abandoned vehicles, trash, and deplorable property, they assume that authorities do not care and do not take active approaches to correct problems in these areas. Therefore, correcting the small problems prevents more serious criminal activity.[86]

Building upon these earlier models, intelligence-led policing has emerged as the dominant philosophy guiding police strategy. Intelligence-led policing and problem-oriented policing are complementary strategies, both which involve systematic use of information.[87] Although it still lacks a universally accepted definition, the crux of intelligence-led policing is an emphasis on the collection and analysis of information to guide police operations, rather than the reverse.[88]

Power restrictions

_SV6_sedan%2C_Western_Australia_Police_(2016-11-12).jpg)

In many nations, criminal procedure law has been developed to regulate officers' discretion, so that they do not arbitrarily or unjustly exercise their powers of arrest, search and seizure, and use of force. In the United States, Miranda v. Arizona led to the widespread use of Miranda warnings or constitutional warnings.

In Miranda the court created safeguards against self-incriminating statements made after an arrest. The court held that "The prosecution may not use statements, whether exculpatory or inculpatory, stemming from questioning initiated by law enforcement officers after a person has been taken into custody or otherwise deprived of his freedom of action in any significant way, unless it demonstrates the use of procedural safeguards effective to secure the Fifth Amendment's privilege against self-incrimination"[89]

Police in the United States are also prohibited from holding criminal suspects for more than a reasonable amount of time (usually 24–48 hours) before arraignment, using torture, abuse or physical threats to extract confessions, using excessive force to effect an arrest, and searching suspects' bodies or their homes without a warrant obtained upon a showing of probable cause. The four exceptions to the constitutional requirement of a search warrant are:

- Consent

- Search incident to arrest

- Motor vehicle searches

- Exigent circumstances

In Terry v. Ohio (1968) the court divided seizure into two parts, the investigatory stop and arrest. The court further held that during an investigatory stop a police officer's search " [is] confined to what [is] minimally necessary to determine whether [a suspect] is armed, and the intrusion, which [is] made for the sole purpose of protecting himself and others nearby, [is] confined to ascertaining the presence of weapons" (U.S. Supreme Court). Before Terry, every police encounter constituted an arrest, giving the police officer the full range of search authority. Search authority during a Terry stop (investigatory stop) is limited to weapons only.[89]

Using deception for confessions is permitted, but not coercion. There are exceptions or exigent circumstances such as an articulated need to disarm a suspect or searching a suspect who has already been arrested (Search Incident to an Arrest). The Posse Comitatus Act severely restricts the use of the military for police activity, giving added importance to police SWAT units.

British police officers are governed by similar rules, such as those introduced to England and Wales under the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE), but generally have greater powers. They may, for example, legally search any suspect who has been arrested, or their vehicles, home or business premises, without a warrant, and may seize anything they find in a search as evidence.

All police officers in the United Kingdom, whatever their actual rank, are 'constables' in terms of their legal position. This means that a newly appointed constable has the same arrest powers as a Chief Constable or Commissioner. However, certain higher ranks have additional powers to authorize certain aspects of police operations, such as a power to authorize a search of a suspect's house (section 18 PACE in England and Wales) by an officer of the rank of Inspector, or the power to authorize a suspect's detention beyond 24 hours by a Superintendent.

Conduct, accountability and public confidence

The Commission for Public Complaints against the RCMP later concluded the use of tear gas against demonstrators at the summit constituted "excessive and unjustified force".[90]

Police services commonly include units for investigating crimes committed by the police themselves. These units are typically called Inspectorate-General, or in the US, "internal affairs". In some countries separate organizations outside the police exist for such purposes, such as the British Independent Police Complaints Commission.

Likewise, some state and local jurisdictions, for example, Springfield, Illinois[91] have similar outside review organizations. The Police Service of Northern Ireland is investigated by the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland, an external agency set up as a result of the Patten report into policing the province. In the Republic of Ireland the Garda Síochána is investigated by the Garda Síochána Ombudsman Commission, an independent commission that replaced the Garda Complaints Board in May 2007.

The Special Investigations Unit of Ontario, Canada, is one of only a few civilian agencies around the world responsible for investigating circumstances involving police and civilians that have resulted in a death, serious injury, or allegations of sexual assault. The agency has made allegations of insufficient cooperation from various police services hindering their investigations.[92]

In Hong Kong, any allegations of corruption within the police will be investigated by the Independent Commission Against Corruption and the Independent Police Complaints Council, two agencies which are independent of the police force.

Due to a long-term decline in public confidence for law enforcement in the United States, body cameras worn by police officers are under consideration.[93]

Use of force

Police forces also find themselves under criticism for their use of force, particularly deadly force. Specifically, tension increases when a police officer of one ethnic group harms or kills a suspect of another one. In the United States, such events occasionally spark protests and accusations of racism against police and allegations that police departments practice racial profiling.

In the United States since the 1960s, concern over such issues has increasingly weighed upon law enforcement agencies, courts and legislatures at every level of government. Incidents such as the 1965 Watts Riots, the videotaped 1991 beating by Los Angeles Police officers of Rodney King, and the riot following their acquittal have been suggested by some people to be evidence that U.S. police are dangerously lacking in appropriate controls.

The fact that this trend has occurred contemporaneously with the rise of the US civil rights movement, the "War on Drugs", and a precipitous rise in violent crime from the 1960s to the 1990s has made questions surrounding the role, administration and scope of police authority increasingly complicated.

Police departments and the local governments that oversee them in some jurisdictions have attempted to mitigate some of these issues through community outreach programs and community policing to make the police more accessible to the concerns of local communities, by working to increase hiring diversity, by updating training of police in their responsibilities to the community and under the law, and by increased oversight within the department or by civilian commissions.

In cases in which such measures have been lacking or absent, civil lawsuits have been brought by the United States Department of Justice against local law enforcement agencies, authorized under the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. This has compelled local departments to make organizational changes, enter into consent decree settlements to adopt such measures, and submit to oversight by the Justice Department.[94]

Protection of individuals

Since 1855, the Supreme Court of the United States has consistently ruled that law enforcement officers have no duty to protect any individual, despite the motto "protect and serve". Their duty is to enforce the law in general. The first such case was in 1855 (South v. State of Maryland (Supreme Court of the United States 1855). Text) and the most recent in 2005 (Town of Castle Rock v. Gonzales).[95]

In contrast, the police are entitled to protect private rights in some jurisdictions. To ensure that the police would not interfere in the regular competencies of the courts of law, some police acts require that the police may only interfere in such cases where protection from courts cannot be obtained in time, and where, without interference of the police, the realization of the private right would be impeded.[96] This would, for example, allow police to establish a restaurant guest's identity and forward it to the innkeeper in a case where the guest cannot pay the bill at nighttime because his wallet had just been stolen from the restaurant table.

In addition, there are Federal law enforcement agencies in the United States whose mission includes providing protection for executives such as the President and accompanying family members, visiting foreign dignitaries, and other high-ranking individuals.[97] Such agencies include the United States Secret Service and the United States Park Police.

International forces

In many countries, particularly those with a federal system of government, there may be several police or police like organizations, each serving different levels of government and enforcing different subsets of the applicable law. The United States has a highly decentralized and fragmented system of law enforcement, with over 17,000 state and local law enforcement agencies.[98]

Some countries, such as Chile, Israel, the Philippines, France, Austria, New Zealand and South Africa, use a centralized system of policing.[99] Other countries have multiple police forces, but for the most part their jurisdictions do not overlap. In the United States however, several different law enforcement agencies may have authority in a particular jurisdiction at the same time, each with their own command.

Other countries where jurisdiction of multiple police agencies overlap, include Guardia Civil and the Policía Nacional in Spain, the Polizia di Stato and Carabinieri in Italy and the Police Nationale and National Gendarmerie in France.[54]

Most countries are members of the International Criminal Police Organization (Interpol), established to detect and fight transnational crime and provide for international co-operation and co-ordination of other police activities, such as notifying relatives of the death of foreign nationals. Interpol does not conduct investigations or arrests by itself, but only serves as a central point for information on crime, suspects and criminals. Political crimes are excluded from its competencies.

See also

- Chief of police

- Constable

- Criminal citation

- Criminal justice

- Fraternal Order of Police

- Highway Patrol

- Law enforcement agency

- Law enforcement and society

- Law enforcement by country

- Militsiya

- Police academy

- Police brutality

- Police certificate

- Police science

- Police state

- Police training officer

- Private police

- Public administration

- Public Security

- Riot police

- Sheriff

- State Police

- The Officer Down Memorial Page, Inc

- Vigilante

- Women in law enforcement

- Police Foundations (Local)

- Lists

- List of basic law enforcement topics

- List of countries by size of police forces

- List of law enforcement agencies

- List of protective service agencies

- Police rank

References

- ↑ "The Role and Responsibilities of the Police" (PDF). Policy Studies Institute. p. xii. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ Walker, Samuel (1977). A Critical History of Police Reform: The Emergence of Professionalism. Lexington, MT: Lexington Books. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-669-01292-7.

- ↑ Neocleous, Mark (2004). Fabricating Social Order: A Critical History of Police Power. Pluto Press. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-0-7453-1489-1.

- ↑ Siegel, Larry J. (2005). Criminolgy. Thomson Wadsworth. pp. 515, 516. Google Books Search

- ↑ Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary, 1999 CD edition

- ↑ "Police". Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ politia, Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, on Perseus Digital Library

- ↑ πολιτεία, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ↑ πόλις, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ↑ Whittaker, Jake. "UC Davis East Asian Studies". University of California, Davis. UCdavis.edu Archived October 7, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hunter, Virginia J. (1994). Policing Athens: Social Control in the Attic Lawsuits, 420-320 B.C. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4008-0392-7.

- 1 2 Clarkson, Charles Tempest; Richardson, J. Hall (1889). Police!. pp. 1–2. OCLC 60726408.

- ↑ Critchley, Thomas Alan (1978). A History of Police in England and Wales.

The Statute of Winchester was the only general public measure of any consequence enacted to regulate the policing of the country between the Norman Conquest and the Metropolitan Police Act, 1829…

- ↑ Coke, Sir Edward (1642). The second part of the Institutes of the lawes of England: Containing the exposition of many ancient, and other statutes; whereof you may see the particulars in a table following…. Printed by M. Flesher and R. Young, for E.D., R.M., W.L. and D.P. p. 77. Retrieved 2012-07-11.

- ↑ "Bicentenaire: theme expo4". prefecture-police-paris.interieur.gouv.fr. Archived from the original on May 6, 2008. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- 1 2 Dick Paterson, Origins of the Thames Police, Thames Police Museum. Retrieved 4 February 2007.

- 1 2 T. A. Critchley, A History of Police in England and Wales, 2nd edition. Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith, 38-39.

- ↑ "Police: The formation of the English Police", Encyclopædia Britannica, 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ↑ "Police: History - The Beginning Of "modern" Policing In England".

- ↑ "Glasgow Police". Scotia-news.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ↑ Kathryn Costello. "Industrial Revolution". Nettlesworth.durham.sch.uk. Archived from the original on May 1, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- ↑ "The National Archives | NDAD | Metropolitan Police". Ndad.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- ↑ "Policing Profiles of Participating and Partner States". POLIS.

- ↑ "Modern Police Force".

- ↑ "A BRIEF GUIDE TO POLICE HISTORY". Archived from the original on September 8, 2009.

- ↑ Timothy Roufa. "The History of Modern Policing: How the Modern Police Force Evolved".

- ↑ Brodeur, Jean-Paul (1992). "High Policing and Low Policing: Remarks about the Policing of Political Activities". In Kevin R. E. McCormick; Livy A. Visano. Understanding Policing. Canadian Scholars' Press. pp. 284–285, 295. ISBN 1-55130-005-2. LCCN 93178368. OCLC 27072058. OL 1500609M.

- ↑ "Metropolitan Police Service – History of the Metropolitan Police Service". Met.police.uk. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- ↑ Taylor, J. "The Victorian Police Rattle Mystery"/ Archived February 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. The Constabulary (2003)

- ↑ Brodeur, Jean-Paul (2010). The Policing Web. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2013-02-07.

- ↑ Dan Zambonini (October 24, 2009). "Joseph Hudson: Inventor of the Police and Referee Whistles".

- ↑ "Respect - Homepage". Together.gov.uk. Archived from the original on December 30, 2005. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ↑ "Historical overview". Interior Security Forces (Lebanon). Archived from the original on June 2, 2006. Retrieved June 26, 2007.

- ↑ Police Service

- ↑ "Why is the colour of the Indian police uniform khaki?". The Times of India. 3 March 2007. Retrieved 2010-05-11.

- ↑ "The history of the Park Police". National Park Service. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ↑ "United States Mint Police". United States Mint. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ↑ "Department History". Philadelphia Police Department. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ↑ "History of the Richmond Police Department". City of Richmond. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ↑ "A Brief History of The B.P.D.". City of Boston. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ↑ "New York City Police Department". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on January 18, 2010. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ↑ "Secret Service History". United States Secret Service. Archived from the original on February 19, 2010. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ↑ "Lists & Structure of Governments". Census.gov. Retrieved 2012-07-11.

- ↑ Linda Greenhouse,"Justices Rule Police Do Not Have a Constitutional Duty to Protect Someone" The New York Times June 28, 2005

- ↑ For more on Von Justi see Security Territory Population p.329 Notes 7 and 8 2007

- ↑ Security,Territory,Population pp.311-332 p.330 Note 11 2007

- ↑ Jürgen Backhaus and Richard E. Wagner, and (2005). Handbook of Public Finance. Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Michel Foucault, Security, Territory, Population, pp.311-332,pp.333-361 1977-78 course published in English 2007

- 1 2 R. J. Marin, "The Living Law." In eds., W. T. McGrath and M. P. Mitchell, The Police Function in Canada. Toronto: Methuen, 1981, 18-19. ISBN 0-458-93920-X

- ↑ Andrew T. Harris, Policing the City: Crime and Legal Authority in London, 1780-1840 PDF. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 2004, 6. ISBN 0-8142-0966-1

- ↑ Marjie Bloy, "Edwin Chadwick (1800-1890)," The Victorian Web.

- ↑ Quoted in H. S. Cooper, "The Evolution of Canadian Police." In eds., W. T. McGrath and M. P. Mitchell, The Police Function in Canada. Toronto: Methuen, 1981, 39. ISBN 0-458-93920-X.

- ↑ Charles Reith, "Preventive Principle of Police," Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology (1931-1951), vol. 34, no. 3 (Sept.-Oct. 1943): 207.

- 1 2 3 Bayley, David H. (1979). "Police Function, Structure, and Control in Western Europe and North America: Comparative and Historical Studies". Crime & Justice. 1: 109–143. doi:10.1086/449060. NCJ 63672.

- ↑ "PMMG". Policiamilitar.mg.gov.br. Archived from the original on July 12, 2008. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ↑ p.Davies, Bruce & McKay, Gary The Men Who Persevered:The AATTV 2005 Bruce & Unwin

- ↑ formerly named SO19 "Metropolitan Police Service - Central Operations, Specialist Firearms unit (CO19)". Metropolitan Police Service. Archived from the original on September 15, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- 1 2 3 Saudi Arabia Catholic priest arrested and expelled from Riyadh - Asia News Archived March 23, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 "Middle East | Saudi minister rebukes religious police". BBC News. 2002-11-04. Retrieved 2012-07-11.

- 1 2 Nadelmann, E. A. (1993) Cops Across Borders; the Internationalization of US Law Enforcement, Pennsylvania State University Press

- ↑ Sheptycki, J. (1995) 'Transnational Policing and the Makings of a Postmodern State', British Journal of Criminology, 1995, Vol. 35 No. 4 Autumn, pp. 613-635

- ↑ Deflem, M. (2002) Policing World Society; Historical Foundations of International Police Cooperation, Oxford: Calrendon

- ↑ Sheptycki, J. (2000) Issues in Transnational Policing, London; Routledge

- ↑ Sheptycki, J. (2002) In Search of Transnational Policing, Aldershot: Ashgate

- ↑ Joubert, C. and Bevers, H. (1996) Schengen Investigated; The Hague: Kluwer Law International

- ↑ Alain, M. (2001) 'The Trapeze Artists and the Ground Crew - Police Cooperation and Intelligence Exchange Mechanisms in Europe and North America: A Comparative Empirical Study', Policing and Society, 11/1: 1-28

- 1 2 Ratcliffe, J. (2007) Strategic Thinking in Criminal Intelligence, Annadale, NSW: The Federation Press

- ↑ Sheptycki, James (2007). "High Policing in the Security Control Society". Policing. 1 (1). pp. 70–79. doi:10.1093/police/pam005. Retrieved 2011-04-09.

- ↑ Goldsmith, A. and Sheptycki, J. (2007) Crafting Transnational Policing; State-Building and Global Policing Reform, Oxford: Hart Law Publishers

- ↑ Hills, A. (2009) 'The Possibility of Transnational Policing, Policing and Society, Vol. 19 No. 3 pp. 300-317

- ↑ Sheptycki, J. (2004) 'The Accountability of Transnational Policing Institutions: The Strange Case of Interpol' The Canadian Journal of Law and Society, Vol. 19 No. 1, pp. 107-134

- ↑ Lloyd, R. Oatham, J. and Hammer, M. (2007) 2007 Global Accountability Report: London: One World Trust

- ↑ "NSW "gobsmacked" at NZ's unarmed force". Television New Zealand. 29 August 2010. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ↑ "Cops 'must shoot to kill'". Retrieved July 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "SA minister defends shoot-to-kill". BBC News. November 12, 2009. Retrieved July 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Dao, James (1996-04-18). "Pataki Curbs Unmarked Cars' Use - The". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ↑ "Police car image".

- ↑ "Car Fire Rescue, Caught On Tape". CBS News. October 19, 2005.

My partner grabbed the fire extinguisher and I ran to the car. We didn't know somebody was in there at first. And then everybody started yelling, 'There's somebody trapped! There's somebody trapped!' And, along with the help of a bunch of citizens, we were able to get him out in the nick of time.

- ↑ "Early Defibrillation". City of Rochester, Minnesota. Archived from the original on July 1, 2010.

- ↑ Reiss Jr; Albert J. (1992). "Police Organization in the Twentieth Century". Crime and Justice. 51: 51. doi:10.1086/449193. NCJ 138800.

- ↑ "Finest of the Finest". TIME Magazine. February 18, 1966. Archived from the original on October 14, 2008.

- ↑ "Guide to the Orlando Winfield Wilson Papers, ca. 1928-1972". Online Archive of California. Retrieved 2006-10-20.

- ↑ "Chicago Chooses Criminologist to Head and Clean Up the Police". United Press International/The New York Times. February 22, 1960.

- ↑ Kelling, George L., Mary A. Wycoff (December 2002). Evolving Strategy of Policing: Case Studies of Strategic Change. National Institute of Justice. NCJ 198029.

- ↑ Kelling, George L., Tony Pate, Duane Dieckman, Charles E. Brown (1974). "The Kansas City Preventive Patrol Experiment - A Summary Report" (PDF). Police Foundation.

- ↑ Kelling, George L., James Q. Wilson (March 1982). "Broken Windows". Atlantic Monthly. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Tilley, Nick (2003). "Problem-Oriented Policing, Intelligence-Led Policing and the National Intelligence Model". Jill Dando Institute of Crime Science, University College London.

- ↑ "Intelligence-led policing: A Definition". Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Archived from the original on May 15, 2006. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- 1 2 Supreme Court of the United States, Terry v. Ohio (No. 67), Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Ohio. Retrieved 2010-05-12 from law.cornell.edu

- ↑ "RCMP used 'excessive force' at Quebec summit: report". CBC News.

- ↑ Amanda Reavy. "Police review board gets started". The State Journal-Register Online.

- ↑ "Star Exclusive: Police ignore SIU's probes". Toronto Star. February 22, 2011.

- ↑ "If Police Encounters Were Filmed". The New York Times. October 22, 2013.

- ↑ Walker, Samuel (2005). The New World of Police Accountability. Sage. p. 5. ISBN 0-534-58158-7.

- ↑ "Castle Rock v. Gonzales". Cornell University Law School. Retrieved 2009-03-21.

- ↑ See e.g. § 1 section 2 of the Police Act of North Rhine-Westphalia: "Police Act of the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia". polizei-nrw.de (in German). Land Nordrhein-Westfalen. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ↑ The United States Park Police Webpage, NPS.gov

- ↑ "Law Enforcement Statistics". Bureau of Justice Statistics. Archived from the original on October 2, 2006. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ↑ Das, Dilip K., Otwin Marenin (2000). Challenges of Policing Democracies: A World Perspective. Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 90-5700-558-1.

Further reading

- Mitrani, Samuel (2014). The Rise of the Chicago Police Department: Class and Conflict, 1850-1894, University of Illinois Press, 272 pages. Interview with Sam Mitrani: The Function of Police in Modern Society: Peace or Control? (January 2015), The Real News

External links

| Look up police in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Media related to Police at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Police at Wikimedia Commons- United Nations Police Division.