Battle of Bloody Marsh

| Battle of Bloody Marsh | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Invasion of Georgia, War of Jenkins' Ear | |||||||

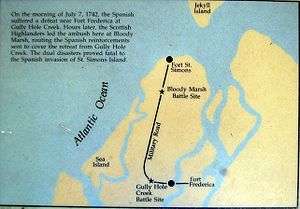

A Map of the Bloody Marsh area as it was in 1742 (North is down) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 650 soldiers, militia and native Indians[1] | 150-200+ soldiers[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Light | Roughly 200 killed[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19] | ||||||

The Battle of Bloody Marsh was a battle that took place on July 7, 1742 (new style) between Spanish and British forces on St. Simons Island, part of the Province of Georgia, resulting in a victory for the British. Part of a much larger conflict known as the War of Jenkins' Ear, the battle was for the British fortifications of Fort Frederica and Fort St. Simons, with the strategic goal the sea routes and inland waters they controlled. With the victory, the Province of Georgia established undisputed claim to the island. It is now part of the U.S. state of Georgia. The British also won the Battle of Gully Hole Creek, which took place on the island the same day.

Background

James Oglethorpe led the colonization of Georgia for Great Britain, and had chosen Savannah as the principal port for the new colony. In the 1730s, Spain and Great Britain were disputing control of the border between Georgia and La Florida, where the Spanish had several settlements and forts.

Given a heightened threat of Spanish invasion, Oglethorpe sought to increase his southern defenses. Accompanied by rangers and two Native American guides, Oglethorpe picked St. Simons Island as the site for a new town and fort. In 1734, Oglethorpe convinced the Parliament and the colonial trustees to pay for a military garrison at the fort.

The trustees also recruited a large group of colonists to settle St. Simons Island. The ships bearing the settlers and supplies arrived at Tybee Island early in 1736. From there, some went to the mainland while others traveled via periaguas (also known as pirogues) to St. Simons Island to found Frederica. The town and its fort were built on the elbow of the Frederica River to control approaches from both directions.

In 1737, Oglethorpe returned to England to acquire more funding and permission to raise a regiment of soldiers; he gained Parliamentary approval for both. He was appointed commander-in-chief of all British forces (limited as they were) in the colonies of South Carolina and Georgia. Oglethorpe subsequently recruited a company of Scots from Inverness, to migrate with their families to settle at Darien (briefly named "New Inverness") on the mainland, at the mouth of the Altamaha River.[20] The men formed a military unit known locally as the Highland Independent Company. Official British records list it as Oglethorpe's Regiment of Foot. It was ranked as 42nd Regiment of Foot (old) in 1747, and disbanded 29 May 1749 in Georgia.[21]

Two forts had been constructed about five miles apart on St. Simons Island. Between the two ran a road the width of one wagon, named Military Road. This served to supply the garrison at Fort Frederica and settlers in the nearby village from Fort St. Simons.

The battles took place after a Spanish invasion of the island. They were part of the larger conflict known as the War of Jenkins' Ear (1739 to 1748). It derived its name from an incident in 1731. A Spanish boarding party had gone aboard a British brig Rebecca, off the Florida coast, and found that its captain Robert Jenkins was smuggling. The Spanish officer cut off one of Jenkins' ears for piracy. Parliament used the nearly forgotten incident to rally public opinion to their side in 1739, but the war was due to trade and territorial competition between Britain and Spain. On October 30, 1739, Great Britain declared war on Spain.

Invasion, battle, and aftermath

Spanish governor Don Manuel de Montiano commanded the invasion force, which by some estimates totaled between 4500 and 5000 men. Of that number, roughly 1900 to 2000 were ground assault troops. Oglethorpe's forces, consisting of regulars, militia, and native Indians, numbered fewer than 1000. The garrison at Fort St. Simons resisted the invasion with cannonade, but could not prevent the landing.

On July 5, 1742 Montiano landed nearly 1900 men from 36 ships near Gascoigne Bluff, close to the Frederica River. Faced with a superior force, Oglethorpe decided to withdraw from Fort St. Simons before the Spanish could mount an assault. He ordered the small garrison to spike the guns and slight the fort (doing what damage they could), to deny the Spanish full use of the military asset. The Spanish took over the remains of the fort the following day, establishing it as their base on the island.

Battle of Gully Hole Creek

After landing troops and supplies, and consolidating their position at Fort St. Simons, the Spanish began to reconnoiter beyond their perimeter. They found the road between Fort St. Simons and Fort Frederica, but assumed the narrow track was just a farm road. On July 18, the Spanish undertook a reconnaissance in force along the road with approximately 115 men under the command of Captain Sebastian Sanchez. One and a half miles from Fort Frederica, Sanchez' column made contact with Oglethorpe's soldiers, under command of Noble Jones. The ensuing skirmish became known as the Battle of Gully Hole Creek. The British routed the Spanish, killing or capturing nearly a third of their soldiers. Oglethorpe's forces advanced along Military Road toward Fort St. Simons in pursuit of the retreating Spanish. When Spanish prisoners revealed that a larger Spanish force was advancing from the opposite direction toward Frederica, Oglethorpe left to gather reinforcements.

Battle of Bloody Marsh

The British advance party, in pursuit of the defeated Spanish force, engaged in a skirmish, then fell back in face of advancing Spanish reinforcements. When the British reached a bend in the road, Lieutenants Southerland and Macoy ordered the column to stop. They took cover in a semi-circle shaped area around a clearing behind trees and palmettos, waiting for the advancing Spanish having taken cover in the dense forest. They watched as the Spanish broke rank, stacked arms and, taking out their kettles, prepared to cook dinner. The Spanish thought they were protected because they had the marsh on one side of them and the forest on the other. The British forces opened fire from behind the cover of trees and bushes, catching the Spanish off-guard. They fired multiple volleys from behind the protection of dense forest. The attack killed roughly 200 Spaniards.[22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33] The ferocity of the fighting at Bloody Marsh was dramatic, and the battle took its name from the tradition that the marsh ran red with the blood of dead Spanish soldiers. The floor of the forest was strewn with the bodies of the dead and dying. A few Spanish officers attempted in vain to reform their ranks, but the Spanish soldiers and their allies fled, panic stricken, in multiple directions as they were hit with volley after volley of musket fire from behind the foliage. Barba himself was captured after being mortally wounded. The Battle of Bloody Marsh blunted the Spanish advance, and ultimately proved decisive. Oglethorpe was credited with the victory, though he arrived at the scene after the fighting had ceased.[34]

Oglethorpe continued to press the Spanish, trying to dislodge them from the island. A few days later, approaching a Spanish settlement on the south side, he learned of a French man who had deserted the British and gone to the Spanish. Worried that the deserter might report how small the British force was, Oglethorpe spread out his drummers, to make them sound as if they were accompanying a larger force. He wrote to the deserter, addressing him as if he were a spy for the British, saying that the man just needed to continue his stories until Britain could send more men. The prisoner who was carrying the letter took it to the Spanish officers, as Oglethorpe had hoped and the Spanish promptly executed the Frenchmen. The timely arrival of British ships reinforced a misconception among the Spanish that British reinforcements were arriving. The Spanish left St. Simons on 25 July, ending their last invasion of colonial Georgia.[35][36][37][38][39]

Aftermath

In the ensuing months, Oglethorpe considered counter-attacks against Florida, but circumstances were not favourable. The focus of the war had shifted from the Americas to Europe; arms, supplies and troops were not readily available. The region settled into an uneasy peace, occasionally punctuated by minor skirmishes. Oglethorpe was later appointed brigadier general. About 1744 he left Georgia for Britain, where he married an heiress; he lived in Britain the rest of his life. The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle ended the war in 1748 and recognised the status of Georgia as a British colony, formally ratified by Spain in the subsequent Treaty of Madrid. Its position was further secured in 1763 when Spain ceded Florida to Britain in an exchange of territory under the Treaty of Paris ending the Seven Years' War.

Wormsloe Plantation in Savannah, Georgia annually commemorates the War of Jenkins' Ear.[40]

-

Bloody Marsh in 2008

-

Bloody Marsh monument

-

Bloody Marsh plaque, July 7, 1742 (Old Style)

-

Modern map of the area

-

Bloody Marsh, with historical marker, 2015

-

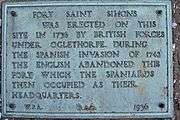

Fort St. Simons marker

See also

- Province of Georgia: about Colonial Georgia

- List of conflicts in the United States

- List of Regiments of Foot (Oglethorpe's 42nd Regiment)

- Invasion of Georgia (1742)

- Fort Frederica National Monument (the Bloody Marsh Battle Site is a unit of the Fort Frederica National Monument)

- Wormsloe Plantation

Notes

- ↑ Marley p. 261

- ↑ Marley p.262

- ↑ Georgia History Stories By Joseph Harris Chappell page 106

- ↑ Life of General Oglethorpe By Henry Bruce page 218

- ↑ Georgia Voices: A Documentary History to 1872 By Spencer Bidwell King page 23

- ↑ Colonial America by Bonnie L. Lukes (Cengage Gale, Jan 4, 1999) page 105

- ↑ Colonial America, 1607-1763 by Harry M. Ward (Prentice Hall, 1991)

- ↑ History of Georgia By Robert Preston Brooks page 77

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=QA_VAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA77&dq=History+of+Georgia++By+Robert+Preston+%22About+two+hundred+Spaniards%22&hl=en&sa=X&ei=XejuVKb7BZSZoQTH2oHoBw&ved=0CB8Q6wEwAA#v=onepage&q=History%20of%20Georgia%20%20By%20Robert%20Preston%20%22About%20two%20hundred%20Spaniards%22&f=false

- ↑ Florida's Past: People and Events That Shaped the State, Volume 1 By Gene M. Burnett page 181

- ↑ The American Colonial Wars: a concise history, 1607-1775 Nathaniel Claiborne Hale, General Society of Colonial Wars (U.S.) Hale House, 1967 page 54

- ↑ Society of Colonial Wars, 1892-1967: seventy-fifth anniversary (General Society of Colonial Wars, 1967) page 231

- ↑ Thomas Spalding of Sapelo, Ellis Merton Coulter, (Louisiana State University Press, 1940) page 278

- ↑ A History of Florida By Caroline Mays Brevard, Henry Eastman Bennett page 75

- ↑ Cate, Margaret Davis. 1943. Fort Frederica and the Battle of Bloody Marsh. The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 27, no. 2: 111-174.

- ↑ 1943. Minutes of the Proceedings Held on St. Simons Island, Georgia, in Commemoration of the Two Hundredth Anniversary of the Battle of Bloody Marsh, on July 7, 1942. The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 27, no. 2: 182-207.

- ↑ Hicky, Daniel Whitehead. 1937. Fort Frederica. The North American Review. 243, no. 2: 249.

- ↑ Cotter, John L. 1963. The Fort at Frederica. American Antiquity. 28, no. 3: 404.

- ↑ Murphy, Jordan, and Ronald C Meyer. 2008. Fort Frederica National Monument (Georgia). New York, NY: Ambrose Video Pub.

- ↑ "History of Darien, Georgia". Cityofdarienga.com. Retrieved 2012-10-16.

- ↑ Swinson (1972), p.137

- ↑ Georgia History Stories By Joseph Harris Chappell page 106

- ↑ Life of General Oglethorpe By Henry Bruce page 218

- ↑ Georgia Voices: A Documentary History to 1872 By Spencer Bidwell King page 23

- ↑ Colonial America by Bonnie L. Lukes (Cengage Gale, Jan 4, 1999) page 105

- ↑ Colonial America, 1607-1763 by Harry M. Ward (Prentice Hall, 1991)

- ↑ History of Georgia By Robert Preston Brooks page 77

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=QA_VAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA77&dq=History+of+Georgia++By+Robert+Preston+%22About+two+hundred+Spaniards%22&hl=en&sa=X&ei=XejuVKb7BZSZoQTH2oHoBw&ved=0CB8Q6wEwAA#v=onepage&q=History%20of%20Georgia%20%20By%20Robert%20Preston%20%22About%20two%20hundred%20Spaniards%22&f=false

- ↑ Florida's Past: People and Events That Shaped the State, Volume 1 By Gene M. Burnett page 181

- ↑ The American Colonial Wars: a concise history, 1607-1775 Nathaniel Claiborne Hale, General Society of Colonial Wars (U.S.) Hale House, 1967 page 54

- ↑ Society of Colonial Wars, 1892-1967: seventy-fifth anniversary (General Society of Colonial Wars, 1967) page 231

- ↑ Thomas Spalding of Sapelo, Ellis Merton Coulter, (Louisiana State University Press, 1940) page 278

- ↑ A History of Florida By Caroline Mays Brevard, Henry Eastman Bennett page 75

- ↑ A history of Georgia: from its first discovery by Europeans to the adoption of the present constitution by William Bacon Stevens page 189

- ↑ Cate, Margaret Davis. 1943. Fort Frederica and the Battle of Bloody Marsh. The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 27, no. 2: 111-174.

- ↑ 1943. Minutes of the Proceedings Held on St. Simons Island, Georgia, in Commemoration of the Two Hundredth Anniversary of the Battle of Bloody Marsh, on July 7, 1942. The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 27, no. 2: 182-207.

- ↑ Hicky, Daniel Whitehead. 1937. Fort Frederica. The North American Review. 243, no. 2: 249.

- ↑ Cotter, John L. 1963. The Fort at Frederica. American Antiquity. 28, no. 3: 404.

- ↑ Murphy, Jordan, and Ronald C Meyer. 2008. Fort Frederica National Monument (Georgia). New York, NY: Ambrose Video Pub.

- ↑ "Wormsloe Historic Site | Georgia State Parks". Gastateparks.org. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

References

- Brown, Ira L. The Georgia Colony. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1970.

- Cate, Maraget D. Our Today's and Yesterdays: a Story of Brunswick and the Coastal Islands, 1972. Spartanburg: The Reprint Company, 1979.

- Coleman, Kenneth (1991), A History of Georgia, Athens, USA: University of Georgia Press, ISBN 978-0-8203-1269-9

- Hull, Barbara. St. Simons: Enchanted Island, Atlanta: Cherokee Company, 1980.

- Ivers, Larry E. British Drums on the Southern Frontier: The Military Colonization of Georgia, 1733-1749, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1974.

- Lovell, Caroline C. The Golden Isles of Georgia, Atlanta Little, Brown and Company in Association with the Atlantic Monthly Company, 1932.

- Marley, David (1998), Wars of the Americas: a chronology of armed conflict in the New World, 1492 to the present, Santa Barbara, USA: ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-0-87436-837-6

- Martínez Láinez, Fernando; Canales, Carlos (2009), Banderas lejanas: la exploración, conquista y defensa por España del territorio de los actuales Estados Unidos, Madrid, Spain: EDAF, ISBN 978-84-414-2119-6

- Swinson, Arthur (1972). A Register of the Regiments and Corps of the British Army. London: The Archive Press. ISBN 0-85591-000-3.

- Sutherland, Patrick. "An Account of the Battle of Bloody Marsh." Georgia Records from Duke University, 1988-0015m, Georgia Archives. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- Sweet, Julie A. "Battle of Bloody Marsh." New Georgia Encyclopedia. 13 Feb. 2003. Baylor University. 26 Sept. 2007 Georgia Encyclopedia.

- "The Battle of Bloody Marsh." Our Georgia History. 27 Sept. 2007 Our Georgia History.

External links

- United States National Park Service

- An Account of the Battle of Bloody Marsh, 1742 from the collection of the Georgia Archives.

- Google Maps showing location

- President Calvin Coolidge at Battle of Bloody Marsh Monument, 1927-1928 from Vanishing Georgia, Georgia Archives, University System of Georgia

- The Spanish on Jekyll Island historical marker