Blood libel

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

Part of Jewish history |

|

Antisemitism on the Web |

|

Opposition |

|

|

Blood libel (also blood accusation)[1][2] is an accusation[3][4][5] that Jews kidnapped and murdered the children of Christians in order to use their blood as part of their religious rituals during Jewish holidays.[1][2][6] Historically, these claims – alongside those of well poisoning and host desecration – have been a major theme of the persecution of Jews in Europe.[4]

Blood libels typically say that Jews require human blood for the baking of matzos for Passover, although this element was allegedly absent in the earliest cases which claimed that (contemporary) Jews reenacted the crucifixion. The accusations often assert that the blood of the children of Christians is especially coveted, and, historically, blood libel claims have been made in order to account for the otherwise unexplained deaths of children. In some cases, the alleged victim of human sacrifice has become venerated as a martyr, a holy figure around whom a martyr cult might arise. Three of these – William of Norwich, Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln, and Simon of Trent – became objects of local cults and veneration, and in some cases they were added to the General Roman Calendar. One, Gavriil Belostoksky, was canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church.

In Jewish lore, blood libels were the impetus for the creation of the Golem of Prague by Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel in the 16th century.[7] According to Walter Laqueur:

Altogether, there have been about 150 recorded cases of blood libel (not to mention thousands of rumors) that resulted in the arrest and killing of Jews throughout history, most of them in the Middle Ages. In almost every case, Jews were murdered, sometimes by a mob, sometimes following torture and a trial.[8]

The term 'blood libel' can also refer to any unpleasant and damaging false accusation, and has taken on a broader metaphorical meaning. However, this usage remains controversial and has been protested by Jewish groups.[9][10][11]

Actual Jewish practices regarding blood and sacrifice

| “ | It has been one of history's cruel ironies that the blood libel — accusations against Jews using the blood of murdered gentile children for the making of wine and matzot — became the false pretext for numerous pogroms. And due to the danger, those who live in a place where blood libels occur are halachically exempted from using red wine, lest it be seized as "evidence" against them. | ” |

| — Pesach: What We Eat and Why We Eat It, Project Genesis[12] | ||

The supposed torture and human sacrifice alleged in the blood libels run contrary to the teachings of Judaism. According to the Bible, God commanded Abraham in the Binding of Isaac to sacrifice his son, but ultimately provided a ram as a substitute. The Ten Commandments in the Torah forbid murder. In addition, the use of blood (human or otherwise) in cooking is prohibited by the kosher dietary laws (kashrut). Blood from slaughtered animals may not be consumed, and must be drained out of the animal and covered with earth (Lev 17:12-13). According to the Book of Leviticus, blood from sacrificed animals may only be placed on the altar of the Great Temple in Jerusalem (which no longer existed at the time of the Christian blood libels). Furthermore, consumption of human flesh would violate kashrut.[13]

While animal sacrifice was part of the practice of ancient Judaism, the Tanakh (Old Testament) and Jewish teachings portray human sacrifice as one of the evils that separated the pagans of Canaan from the Hebrews (Deut 12:31, 2 Kings 16:3). Jews were prohibited from engaging in these rituals and were punished for doing so (Ex 34:15, Lev 20:2, Deut 18:12, Jer 7:31). In fact, ritual cleanliness for priests prohibited them from even being in the same room as a human corpse (Lev 21:11).

History

The earliest versions of the accusation involved Jews crucifying Christian children at Easter/Passover because of a prophecy. There is no reference to the use of blood in unleavened matzo bread, which evolves later as a major motivation for the crime.[14]

Possible precursors

Though otherwise very different from the medieval myth, there are two records of ancient stories about Jewish acts of sacrifice that have been linked to the later blood libel stories of the medieval era. The first is in the writings of the Graeco-Egyptian author Apion, who claimed that Jews sacrificed Greek victims in their temple. This accusation is known from Josephus' rebuttal of it in Against Apion. Apion states that when Antiochus Epiphanes entered the temple in Jerusalem, he discovered a Greek captive who told him he was being fattened for sacrifice. Every year, Apion claimed, the Jews would sacrifice a Greek and consume his flesh, at the same time swearing eternal hatred to Greeks.[15] Apion's claim probably repeats ideas already in circulation as similar claims are made by Posidonius and Apollonius Molon in the 1st century BC.[16] The second story concerns the murder of a Christian boy by a group of Jewish youths. Socrates Scholasticus (fl. 5th Century) reported that some Jews in a drunken frolic bound a Christian child on a cross in mockery of the death of Christ and scourged him until he died.[17]

Professor Israel Jacob Yuval of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem published an article in 1993 that argues that blood libel may have originated in the 12th century from Christian views of Jewish behavior during the First Crusade. Some Jews committed suicide and killed their own children rather than be subjected to forced conversions. Yuval investigated Christian reports of these events and found that they were greatly distorted with claims that if Jews could kill their own children they could also kill the children of Christians. Yuval rejects the blood libel story as a fantasy of some Christians which could not contain any elements of truth because of the precarious nature of the Jewish minority's existence in Christian Europe.[18][19]

Origins in England

In England in 1144, Jews of Norwich were accused of ritual murder after a boy, William of Norwich, was found dead with stab wounds in the woods. William's hagiographer, Thomas of Monmouth, claimed that every year there is an international council of Jews at which they choose the country in which a child will be killed during Easter, because, he claimed, of a Jewish prophecy that states that the killing of a Christian child each year will ensure that the Jews will be restored to the Holy Land. In 1144, England was chosen, and the leaders of the Jewish community delegated the Jews of Norwich to perform the killing. They then abducted and crucified William.[20] The legend was turned into a cult, with William acquiring the status of a martyr and pilgrims bringing offerings to the local church.[21]

This was followed by similar accusations in Gloucester (1168), Bury St Edmunds (1181) and Bristol (1183). In 1189, the Jewish deputation attending the coronation of Richard the Lionheart was attacked by the crowd. Massacres of Jews at London and York soon followed. In 1190 on March 16, 150 Jews were attacked in York and then massacred when they took refuge in the royal castle, where Clifford's Tower now stands, with some committing suicide rather than being taken by the mob.[22] The remains of 17 bodies thrown in a well in Norwich between the 12th and 13th century (five that were shown by DNA testing to likely be members of a single Jewish family) were very possibly killed as part of one of these pogroms.[23]

After the death of Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln, there were a series of trials and executions of Jews.[24] The case is mentioned by Chaucer, and thus has become well-known. The eight-year-old Hugh disappeared at Lincoln on 31 July 1255. His body was discovered on 29 August, covered with filth, in a pit or well belonging to a Jewish man named Copin or Koppin. On being promised by John of Lexington, a judge, who happened to be present, that his life should be spared, Copin is said to have confessed that the boy had been crucified by the Jews, who had assembled at Lincoln for that purpose. King Henry III, on reaching Lincoln at the beginning of October, refused to carry out the promise of John of Lexington, and had Copin executed and 91 of the Jews of Lincoln seized and sent up to London, where 18 of them were executed. The rest were pardoned at the intercession of the Franciscans (Jacobs, Jewish Ideals, pp. 192–224). Within a few decades, Jews would be expelled from all of England in 1290 and not allowed to return until 1657.

Continental Europe

The first known case outside England was in Blois, France, in 1171. This was the site of a blood libel accusation against the town's entire Jewish community that led to around 31 Jews[25] being burned to death.[26][27] The blood libel revolved around Isaac bar Eleazar, a Jewish resident of Blois, who was accused by a Christian servant of throwing a child into a watering hole. The child's body was never found, and all the Jews who lived in Blois were killed for the alleged ritual murder.[25] Thomas of Monmouth's story of the annual Jewish meeting to decide which local community would kill a Christian child also quickly spread to the continent. An early version appears in Bonum Universale de Apibus ii. 29, § 23, by Thomas of Cantimpré (a monastery near Cambray). Thomas wrote "It is quite certain that the Jews of every province annually decide by lot which congregation or city is to send Christian blood to the other congregations." Thomas of Cantimpré also believed that since the time when the Jews called out to Pontius Pilate, "His blood be on us, and on our children" (Matthew 27:25), they have been afflicted with hemorrhages:

A very learned Jew, who in our day has been converted to the (Christian) faith, informs us that one enjoying the reputation of a prophet among them, toward the close of his life, made the following prediction: 'Be assured that relief from this secret ailment, to which you are exposed, can only be obtained through Christian blood ("solo sanguine Christiano").' This suggestion was followed by the ever-blind and impious Jews, who instituted the custom of annually shedding Christian blood in every province, in order that they might recover from their malady.

Thomas added that the Jews had misunderstood the words of their prophet, who by his expression "solo sanguine Christiano" had meant not the blood of any Christian, but that of Jesus – the only true remedy for all physical and spiritual suffering. Thomas did not mention the name of the "very learned" proselyte, but it may have been Nicholas Donin of La Rochelle, who in 1240 had a disputation on the Talmud with Yechiel of Paris, and who in 1242 caused the burning of numerous Talmudic manuscripts in Paris. It is known that Thomas was personally acquainted with this Nicholas.

At Pforzheim, Baden, the corpse of a seven-year-old girl was found in the river by fishermen. The Jews were suspected, and when they were led to the corpse, blood allegedly began to flow from the wounds; led to it a second time, the face of the child became flushed, and both arms were raised. In addition to these miracles, there was the testimony of the daughter of the wicked woman who had sold the child to the Jews. A regular judicial examination did not take place; it is probable that the above-mentioned "wicked woman" was the murderer. That a judicial murder was then and there committed against the Jews in consequence of the accusation is evident from the manner in which the Nuremberg "Memorbuch" and the synagogal poems refer to the incident (Siegmund Salfeld, Das Martyrologium des Nürnberger Memorbuches (1898), pp. 15, 128–130).

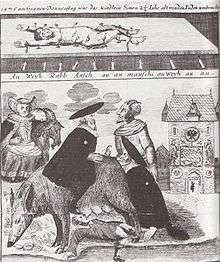

At Weissenburg, a miracle alone decided the charge against the Jews. According to the accusation, the Jews had suspended a child (whose body was found in the Lauter river) by the feet, and had opened every artery in his body to obtain all the blood. Again, supernatural claims were made: the child's wounds were said to have bled for five days afterward, despite its treatment.

At Oberwesel, "miracles" again constituted the only evidence against the Jews. The corpse of the 11-year-old Werner of Oberwesel was said to have floated up the Rhine (against the current) as far as Bacharach, emitting radiance, and being invested with healing powers. In consequence, the Jews of Oberwesel and many other adjacent localities were severely persecuted during the years 1286-89. Emperor Rudolph I, to whom the Jews had appealed for protection, issued a public proclamation to the effect that great wrong had been done to the Jews, and that the corpse of Werner was to be burned and the ashes scattered to the winds.

A statement was made, in the "Chronicle" of Konrad Justinger of 1423, that at Bern in 1294 the Jews tortured and murdered a boy called Rudolph. The historical impossibility of this widely credited story was demonstrated by Jakob Stammler, pastor of Bern, in 1888.[28] It has been speculated whether the Kindlifresserbrunnen ("Child Eater Fountain") in Bern might refer to the alleged ritual murder of 1294.

Renaissance and Baroque

Simon of Trent, aged two, disappeared, and his father alleged that he had been kidnapped and murdered by the local Jewish community. Fifteen local Jews were sentenced to death and burned. Simon was regarded locally as a saint, although he was never canonised by the church of Rome under Pope Sixtus V in 1588. His local status as a saint was removed in 1965 by Pope Paul VI.

Christopher of Toledo, also known as Christopher of La Guardia or "the Holy Child of La Guardia," was a four-year-old Christian boy supposedly murdered by two Jews and three Conversos (converts to Christianity). In total, eight men were executed. It is now believed[29] that this case was constructed by the Spanish Inquisition to facilitate the expulsion of Jews from Spain. He was canonized by Pope Pius VII in 1805. Christopher has since been removed from the canon.

In a case at Tyrnau (Nagyszombat, today Trnava, Slovakia), the absurdity, even the impossibility, of the statements forced by torture from women and children shows that the accused preferred death as a means of escape from the torture, and admitted everything that was asked of them. They even said that Jewish men menstruated, and that the latter therefore practiced the drinking of Christian blood as a remedy.

At Bösing (Bazin, today Pezinok, Slovakia), it was charged that a nine-year-old boy had been bled to death, suffering cruel torture; thirty Jews confessed to the crime and were publicly burned. The true facts of the case were disclosed later, when the child was found alive in Vienna. He had been taken there by the accuser, Count Wolf of Bazin, as a means of ridding himself of his Jewish creditors at Bazin.

At Rinn, near Innsbruck, a boy named Andreas Oxner (also known as Anderl von Rinn) was said to have been bought by Jewish merchants and cruelly murdered by them in a forest near the city, his blood being carefully collected in vessels. The accusation of drawing off the blood (without murder) was not made until the beginning of the 17th century, when the cult was founded. The older inscription in the church of Rinn, dating from 1575, is distorted by fabulous embellishments – for example, that the money paid for the boy to his godfather turned into leaves, and that a lily blossomed upon his grave. The cult continued until officially prohibited in 1994, by the Bishop of Innsbruck.[30]

On 17 January 1670 Raphael Levy, a member of the Jewish community of Metz, was executed on charges of the ritual murder of a peasant child who had gone missing in the woods outside the village of Glatigny on 25 September 1669, the eve of Rosh Hashanah.[31]

19th century

The only child-saint in the Russian Orthodox Church is the six-year-old boy Gavriil Belostoksky from the village Zverki. According to the legend supported by the church, the boy was kidnapped from his home during the holiday of Passover while his parents were away. Shutko, who was a Jew from Białystok, was accused of bringing the boy to Białystok, poking him with sharp objects and draining his blood for nine days, then bringing the body back to Zverki and dumping it at a local field. A cult developed, and the boy was canonized in 1820. His relics are still the object of pilgrimage. On All Saints Day, July 27, 1997, the Belorussian state TV showed a film alleging the story is true.[32] The revival of the cult in Belarus was cited as a dangerous expression of antisemitism in international reports on human rights and religious freedoms[33][34][35][36][37] which were passed to the UNHCR.[38]

- 1823–35 Velizh blood libel: After a Christian child was found murdered outside of this small Russian town in 1823, accusations by a drunk prostitute led to the imprisonment of many local Jews. Some were not released until 1835.

- 1840 Damascus affair: In February, at Damascus, a Catholic monk named Father Thomas and his servant disappeared. The accusation of ritual murder was brought against members of the Jewish community of Damascus.

- 1840 Rhodes blood libel: The Jews of Rhodes, under the Ottoman Empire, were accused of murdering a Greek Christian boy. The libel was supported by the local governor and the European consuls posted to Rhodes. Several Jews were arrested and tortured, and the entire Jewish quarter was blockaded for twelve days. An investigation carried out by the central Ottoman government found the Jews to be innocent.

- In 1840, David Drach, the son of the Head Rabbi of Paris and a convert to Christianity, wrote in his book De L’harmonie Entre L’eglise et la Synagogue, that a Catholic priest in Damascus in that year had been ritually killed and the murder covered up by powerful Jews in Europe.

- In March 1879, ten Jewish men from a mountain village were brought to Kutaisi, Georgia to stand trial for the alleged kidnapping and murder of a Christian girl. The case attracted a great deal of attention in Russia (of which Georgia was then a part): "While periodicals as diverse in tendency as Herald of Europe and Saint Petersburg Notices expressed their amazement that medieval prejudice should have found a place in the modern judiciary of a civilized state, New Times hinted darkly of strange Jewish sects with unknown practices."[39] The trial ended in acquittal, and the orientalist Daniel Chwolson published a refutation of the blood libel.

- 1882 Tiszaeszlár blood libel: The Jews of the village of Tiszaeszlár, Hungary were accused of the ritual murder of a fourteen-year-old Christian girl, Eszter Solymosi. The case was one of the main causes of the rise of antisemitism in the country. The accused persons were eventually acquitted.

- In 1899 Hilsner Affair: Leopold Hilsner, a Jewish vagabond, was accused of murdering a nineteen-year-old Christian woman, Anežka Hrůzová, with a slash to the throat. Despite the absurdity of the charge and the relatively progressive nature of society in Austria-Hungary, Hilsner was convicted and sentenced to death. He was later convicted of an additional unsolved murder, also involving a Christian woman. In 1901, the sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. Tomáš Masaryk, a prominent Austro-Czech philosophy professor and future president of Czechoslovakia, spearheaded Hilsner's defense. He was later blamed by Czech media because of this. In March 1918, Hilsner was pardoned by Austrian emperor Charles I. He was never exonerated, and the true guilty parties were never found.

20th century and beyond

- The 1903 Kishinev pogrom, an anti-Jewish revolt, started when an anti-Semitic newspaper wrote that a Christian Russian boy, Mikhail Rybachenko, was found murdered in the town of Dubossary, alleging that the Jews killed him in order to use the blood in preparation of matzo. Around 49 Jews were killed and hundreds were wounded, with over 700 houses being looted and destroyed.

- In the 1910 Shiraz blood libel, the Jews of Shiraz, Iran, were falsely accused of murdering a Muslim girl. The entire Jewish quarter was pillaged; the pogrom left 12 Jews dead and about 50 injured.

- In Kiev, a Jewish factory manager, Menahem Mendel Beilis, was accused of murdering Andrei Yushchinsky, a Christian child, and using his blood in matzos. He was acquitted by an all-Christian jury after a sensational trial in 1913.[40]

- In 1928, the Jews of Massena, New York, were falsely accused of kidnapping and killing a Christian girl in the Massena blood libel.

- Jews were frequently accused of the ritual murder of Christians for their blood in Der Stürmer, an antisemitic newspaper published in Nazi Germany. The infamous May 1934 issue of the paper was later banned by the Nazi authorities, because it went so far as to compare alleged Jewish ritual murder with the Christian rite of communion.[41]

- In 1938 the British fascist politician and veterinarian Arnold Leese published an antisemitic booklet in defense of the Blood Libel titled My Irrelevant Defense: Meditations inside Gaol and Out on Jewish Ritual Murder.

- The 1944-1946 Anti-Jewish violence in Poland, which by some estimates killed as many as 1000–2000 Jews (237 documented cases)[42]), involved, among other elements, accusations of blood libel, especially in the case of the 1946 Kielce pogrom.

- King Faisal of Saudi Arabia (r. 1964–1975) made accusations against Parisian Jews that took the form of a blood libel.[43]

- The Matzah Of Zion was written by the Syrian Defense Minister, Mustafa Tlass in 1986. The book concentrates on two issues: renewed ritual murder accusations against the Jews in the Damascus affair of 1840, and The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.[44] The book was cited at a United Nations conference in 1991 by a Syrian delegate. On October 21, 2002, the London-based Arabic paper Al-Hayat reported that the book The Matzah of Zion was undergoing its eighth reprinting and was being translated into English, French and Italian. Egyptian filmmaker Munir Radhi has announced plans to adapt the book into a film.[45]

- In 2003, a private Syrian film company created a 29-part television series Ash-Shatat ("The Diaspora"). This series originally aired in Lebanon in late 2003 and was broadcast by Al-Manar, a satellite television network owned by Hezbollah. This TV series, based on the antisemitic forgery The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, shows the Jewish people as engaging in a conspiracy to rule the world, and presents Jews as people who murder the children of Christians, drain their blood and use this blood to bake matzah.

- In early January 2005, some 20 members of the Russian State Duma publicly made a blood libel against the Jewish people. They approached the Prosecutor General’s Office and demanded that Russia "ban all Jewish organizations.” They accused all Jewish groups of being extremists and of being “anti-Christian and inhumane, which practices extend even to ritual murders.” Alluding to previous antisemitic Russian court decrees that accused the Jews of ritual murder, they wrote that “Many facts of such religious extremism were proven in courts.” The accusation included traditional antisemitic canards, such as “the whole democratic world today is under the financial and political control of international Jewry. And we do not want our Russia to be among such unfree countries”. This demand was published as an open letter to the prosecutor general, in Rus Pravoslavnaya (Russian: Русь православная, "Orthodox Russia"), a national-conservative newspaper. This group consisted of members of the ultra-nationalist Liberal Democrats, the Communist faction, and the nationalist Motherland party, with some 500 supporters. Тhe mentioned document is known as "The Letter of Five Hundred" ("Письмо пятисот").[46][47] Their supporters included editors of nationalist newspapers as well as journalists. By the end of the month this group had received stiff criticism, and retracted its demand.

- At the end of April 2005, five boys, ages 9 to 12, in Krasnoyarsk (Russia) disappeared. In May 2005, their burnt bodies were found in the city sewage. The crime was not disclosed, and in August 2007 the investigation was extended until November 18, 2007.[48] Some Russian nationalist groups claimed that the children were murdered by a Jewish sect with a ritual purpose.[49][50] Nationalist M. Nazarov, one of the authors of "The Letter of Five Hundred" alleges "the existence of a 'Hasidic sect', whose members kill children before Passover to collect their blood," using the Beilis case mentioned above as evidence. M.Nazarov also alleges that "the ritual murder requires throwing the body away rather than its concealing". "The Union of the Russian People" demanded officials thoroughly investigate the Jews, not stopping at the search in synagogues, Matzah bakeries and their offices.[51]

- During a speech in 2007, Raed Salah, the leader of the northern branch of the Islamic Movement in Israel, accused Jews of using children's blood to bake bread. "We have never allowed ourselves to knead [the dough for] the bread that breaks the fast in the holy month of Ramadan with children's blood," he said. "Whoever wants a more thorough explanation, let him ask what used to happen to some children in Europe, whose blood was mixed in with the dough of the [Jewish] holy bread." [52]

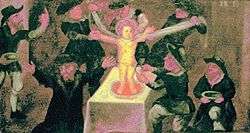

- In 2008, a Polish team of anthropologists and sociologists investigated the currency of the blood libel myth in Sandomierz where a painting depicting the blood libel adorns the Cathedral, and they discovered that these beliefs persist among Catholic and Orthodox Christians of all social classes.[53][54][55]

- In an address that aired on Al-Aqsa TV, a Hamas run TV station in Gaza, on March 31, 2010, Salah Eldeen Sultan (Arabic: صلاح الدين سلطان), founder of the American Center for Islamic Research in Columbus, Ohio, the Islamic American University in Southfield, Michigan, and the Sultan Publishing Co.[56] and described in 2005 as "one of America's most noted Muslim scholars," alleged that Jews kidnap Christians and others in order to slaughter them and use their blood for making matzos. Sultan, who is currently a lecturer of Muslim jurisprudence at the Cairo University stated that: "The Zionists kidnap several non-Muslims [sic] – Christians and others... this happened in a Jewish neighborhood in Damascus. They killed the French doctor, Toma, who used to treat the Jews and others for free, in order to spread Christianity. Even though he was their friend and they benefited from him the most, they took him on one of these holidays and slaughtered him, along with the nurse. Then they kneaded the matzos with the blood of Dr. Toma and his nurse. They do this every year. The world must know these facts about the Zionist entity and its terrible corrupt creed. The world should know this." (Translation by the Middle East Media Research Institute)[57][58][59][60][61]

- During an interview which aired on Rotana Khalijiya TV on August 13, 2012, Saudi Cleric Salman Al-Odeh stated (as translated by MEMRI) that "It is well known that the Jews celebrate several holidays, one of which is the Passover, or the Matzos Holiday. I read once about a doctor who was working in a laboratory. This doctor lived with a Jewish family. One day, they said to him: 'We want blood. Get us some human blood.' He was confused. He didn't know what this was all about. Of course, he couldn't betray his work ethics in such a way, but he began inquiring, and he found that they were making matzos with human blood." Al-Odeh also stated that "[Jews] eat it, believing that this brings them close to their false god, Yahweh" and that "They would lure a child in order to sacrifice him in the religious rite that they perform during that holiday."[62][63]

- In April 2013, the Palestinian non-profit organization MIFTAH, founded by Hanan Ashrawi apologized for publishing an article which criticized US President Barack Obama for holding a Passover Seder in the White House by saying "Does Obama in fact know the relationship, for example, between ‘Passover’ and ‘Christian blood’...?! Or ‘Passover’ and ‘Jewish blood rituals?!’ Much of the chatter and gossip about historical Jewish blood rituals in Europe is real and not fake as they claim; the Jews used the blood of Christians in the Jewish Passover." MIFTAH's apology expressed its "sincerest regret."[64]

- In an interview which aired on Al-Hafez TV on May 12, 2013, Khaled Al-Zaafrani of the Egyptian Justice and Progress Party, stated (as translated by MEMRI): "It's well known that during the Passover, they [the Jews] make matzos called the "Blood of Zion." They take a Christian child, slit his throat and slaughter him. Then they take his blood and make their [matzos]. This is a very important rite for the Jews, which they never forgo... They slice it and fight over who gets to eat Christian blood." In the same interview, Al-Zaafrani stated that "The French kings and the Russian czars discovered this in the Jewish quarters. All the massacring of Jews that occurred in those countries were because they discovered that the Jews had kidnapped and slaughtered children, in order to make the Passover matzos."[65][66][67][68]

- In an interview which aired on the Al-Quds TV channel on July 28, 2014 (as translated by MEMRI), Osama Hamdan, the top representative of Hamas in Lebanon, stated that "we all remember how the Jews used to slaughter Christians, in order to mix their blood in their holy matzos. This is not a figment of imagination or something taken from a film. It is a fact, acknowledged by their own books and by historical evidence."[69] In a subsequent interview with CNN's Wolf Blitzer, Hamdan defended his comments, stating that he "has Jewish friends."[70]

- In a sermon broadcast on the official Jordanian TV channel on August 22, 2014, Sheik Bassam Ammoush, a former Minister of Administrative Development who was appointed to Jordan's House of Senate ("Majlis al-Aayan") in 2011, stated (as translated by MEMRI): "In [the Gaza Strip] we are dealing with the enemies of Allah, who believe that the matzos that they bake on their holidays must be kneaded with blood. When the Jews were in the diaspora, they would murder children in England, in Europe, and in America. They would slaughter them and use their blood to make their matzos... They believe that they are God's chosen people. They believe that the killing of any human being is a form of worship and a means to draw near their god."[71]

Views of the Catholic Church

The attitude of the Roman Catholic Church towards these accusations and the cults venerating children supposedly killed by Jews has varied over time. The Papacy generally opposed them, although it had problems in enforcing its opposition.

In 1911, the Dictionnaire apologétique de la foi catholique, an important French Catholic encyclopedia, published an analysis of the blood libel accusations.[72] This may be taken as being broadly representative of educated Catholic opinion in continental Europe at that time. The article noted that the popes had generally refrained from endorsing the blood libel, and it concluded that the accusations were unproven in a general sense, but it left open the possibility that some Jews had committed ritual murders of Christians. Other contemporary Catholic sources (notably the Jesuit periodical La Civiltà Cattolica) promoted the blood libel as truth.[73]

Today, the accusations are almost entirely discredited in Catholic circles, and the cults associated with them have fallen into disfavour. For example, Simon of Trent was deleted from the Calendar of Saints in 1965 and does not appear in the current (2000) edition of the Roman Martyrology.

Papal pronouncements

- Pope Innocent IV took action against the blood libel: "5 July 1247 "Mandate to the prelates of Germany and France to annul all measures adopted against the Jews on account of the ritual murder libel, and to prevent accusation of Arabs on similar charges" (The Apostolic See and the Jews, Documents: 492–1404; Simonsohn, Shlomo, pp. 188–189, 193–195, 208). In 1247, he wrote also that "Certain of the clergy, and princes, nobles and great lords of your cities and dioceses have falsely devised certain godless plans against the Jews, unjustly depriving them by force of their property, and appropriating it themselves;... they falsely charge them with dividing up among themselves on the Passover the heart of a murdered boy...In their malice, they ascribe every murder, wherever it chance to occur, to the Jews. And on the ground of these and other fabrications, they are filled with rage against them, rob them of their possessions without any formal accusation, without confession, and without legal trial and conviction, contrary to the privileges granted to them by the Apostolic See... Since it is our pleasure that they shall not be disturbed,... we ordain that ye behave towards them in a friendly and kind manner. Whenever any unjust attacks upon them come under your notice, redress their injuries, and do not suffer them to be visited in the future by similar tribulations" (Catholic Encyclopedia (1910), Vol. 8, pp. 393–394).

- Pope Gregory X (1271–1276) issued a letter which criticized the practice of blood libels and forbade arrests and persecution of Jews based on a blood libel, ... unless which we do not believe they be caught in the commission of the crime.[74]

- Pope Paul III, in a bull of 12 May 1540, made clear his displeasure at having learned, through the complaints of the Jews of Hungary, Bohemia and Poland, that their enemies, looking for a pretext to lay their hands on the Jews' property, were falsely attributing terrible crimes to them, in particular that of killing children and drinking their blood.

- St. Pius V in the bull Hebraeorum gens sola (26 February 1569), by which he expelled Jews from all the cities of the Papal States except Rome and Ancona,[75] made multiple accusations of wrong-doing against the Jews, including usury, theft, receiving stolen goods, pimping, divination and magic. He did not mention the blood libel.

- Pope Benedict XIV wrote the bull Beatus Andreas (22 February 1755) in response to an application for the formal canonization of the 15th-century Andreas Oxner, a folk saint alleged to have been murdered by Jews "out of hatred for the Christian faith". Benedict did not dispute the factual claim that Jews murdered Christian children, and in anticipating that further cases on this basis would be brought appears to have accepted it as accurate, but decreed that in such cases beatification or canonization would be inappropriate.[76]

Views of Muslims

In late 1553 or 1554, Suleiman the Magnificent, the reigning Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, issued a firman (royal decree) formally denouncing blood libels against the Jews.[77]

In 1983, Mustafa Tlass wrote and published The Matzah of Zion, which is a treatment of the Damascus affair of 1840 that repeats the ancient "blood libel", that Jews use the blood of murdered non-Jews in religious rituals such as baking Matza bread.[78] In this book, he argues that the true religious beliefs of Jews are "black hatred against all humans and religions," and that no Arab country should ever sign a peace treaty with Israel.[79] Tlass re-printed the book several times, and he stands by its conclusions. Following the book's publication, Tlass told Der Spiegel, that this accusation against Jews was valid and that his book is "an historical study ... based on documents from France, Vienna and the American University in Beirut."[79][80]

In 2003, the Egyptian newspaper Al-Ahram published a series of articles by Osama Al-Baz, a senior advisor to then Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak. Among other things, Osam Al-Baz explained the origins of the blood libel against the Jews. He said that Arabs and Muslims have never been antisemitic, as a group, but accepted that a few Arab writers and media figures attack Jews "on the basis of the racist fallacies and myths that originated in Europe". He urged people not to succumb to "myths" such as the blood libel.[81]

However, the blood libel was featured in a scene in the Syrian TV series Ash-Shatat, shown in 2003,[82][83] while in 2013 the Israeli website Arutz Sheva reported cases of Israeli Arabs asking "where Jews find the Christian blood they need to bake matza".[84]

References

- 1 2 Gottheil, Richard; Strack, Hermann L.; Jacobs, Joseph (1901–1906). "Blood Accusation". Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- 1 2 Dundes, Alan, ed. (1991). The Blood Libel Legend: A Casebook in Anti-Semitic Folklore. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-13114-2.

- ↑ Turvey, Brent E. Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis, Academic Press, 2008, p. 3. "Blood libel: An accusation of ritual murder made against one or more persons, typically of the Jewish faith".

- 1 2 Chanes, Jerome A. Antisemitism: A Reference Handbook, ABC-CLIO, 2004, pp. 34–45. "Among the most serious of these [anti-Jewish] manifestations, which reverberate to the present day, were those of the libels: the leveling of charges against Jews, particularly the blood libel and the libel of desecrating the host.

- ↑ Goldish, Matt. Jewish Questions: Responsa on Sephardic Life in the Early Modern Period, Princeton University Press, 2008, p. 8. "In the period from the twelfth to the twentieth centuries, Jews were regularly charged with blood libel or ritual murder – that Jews kidnapped and murdered the children of Christians as part of a Jewish religious ritual."

- ↑ Zeitlin, S "The Blood Accusation" Vigiliae Christianae, Vol. 50, No. 2 (1996), pp. 117–124

- ↑ Angelo S. Rappoport The Folklore of the Jews (London: Soncino Press, 1937), pp. 195–203 Archived April 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Walter Laqueur (2006): The Changing Face of Antisemitism: From Ancient Times to the Present Day, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-530429-2. p. 56

- ↑ http://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-12176503

- ↑ http://www.nationalreview.com/campaign-spot/256955/term-blood-libel-more-common-you-might-think-jim-geraghty

- ↑ http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748703583404576079823067585318

- ↑ Rutman, Rabbi Yisrael. "Pesach: What We Eat and Why We Eat It". Project Genesis Inc. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ What is kashrut; "Eating blood is forbidden. Blood is blood, whether it comes from a human being or an animal. In prohibiting the consumption of blood, the Torah seems to be concerned that it can excite a blood-lust in human beings and may desensitize us to the suffering of human beings when their blood is spilled."

- ↑ Paul R. Bartrop, Samuel Totten, Dictionary of Genocide, ABC-CLIO, 2007, p. 45.

- ↑ Louis H. Feldman, Jew and Gentile in the Ancient World:Attitudes and Interactions from Alexander to Justinian, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1993. pp. 126–27.

- ↑ Feldman, Louis H. Studies in Hellenistic Judaism, Brill, 1996, p. 293.

- ↑ "Blood libel in Syria". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- ↑ Lily Galili (February 18, 2007). "And if it's not good for the Jews?". Ha'aretz. Retrieved 2007-02-18.

- ↑ Two Nations in Your Womb: Perceptions of Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages by Israel J. Yuval; translated by Barbara Harshav and Jonathan Chipman, University of California Press, 2006

- ↑ Paper on William of Norwich presented to the Jewish Historical Society of England by Raphael Langham; Langmuir, Gavin I (1996), Toward a Definition of Antisemitism, University of California Press, pp. 216ff.

- ↑ "St. William of Norwich". Retrieved 2012-07-12.

- ↑ http://www.historyofyork.org.uk/themes/norman/the-1190-massacre

- ↑ "Jewish bodies found in medieval well in Norwich". BBC News. June 23, 2011.

- ↑ The Knight's Tale of Young Hugh of Lincoln", Gavin I. Langmuir, Speculum, Vol. 47, No. 3 (July 1972), pp. 459–482.

- 1 2 Hallo, William W.; Ruderman, David B.; Stanislawski, Michael, eds. (1984). Heritage: Civilization and the Jews: Source Reader. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Praeger Special Studies. p. 134. ISBN 978-0275916084.

- ↑ "The Martyrs of Blois". Chabad.org. 2006-06-16. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- ↑ Trachtenberg, Joshua, ed. (1943). THE DEVIL AND THE JEWS, The Medieval Conception of the Jew and its Relation to Modern Anti-Semitism. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-8276-0227-8.

- ↑ "Katholische Schweizer-Blätter," Lucerne, 1888.

- ↑ Reston, James: "Dogs of God: Columbus, the Inquisition, and the defeat of the Moors", p. 207. Doubleday, 2005. ISBN 0-385-50848-4

- ↑ Medieval Sourcebook: A Blood Libel Cult: Anderl von Rinn, d. 1462 www.fordham.edu.

- ↑ Edmund Levin, The Exoneration of Raphael Levy, Wall Street Journal, Feb. 2, 2014. Accessed 10 October 2016.

- ↑ Is the New in the Post-Soviet Space Only the Forgotten Old? by Leonid Stonov, International Director of Bureau for the Human Rights and Law-Observance in the Former Soviet Union, the President of the American Association of Jews from the former USSR)

- ↑ Belarus. International Religious Freedom Report 2003 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor

- ↑ Belarus. International Religious Freedom Report 2004 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor

- ↑ Belarus. International Religious Freedom Report 2005 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor

- ↑ Belarus. International Religious Freedom Report 2006 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor

- ↑ "F:\WORK\RELFREE\2003\91075.000" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- ↑ "U.S. Department of State Annual Report on International Religious Freedom for 2006 - Belarus". UNHCR. Archived from the original on 7 September 2007. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ Effie Ambler, Russian Journalism and Politics: The Career of Aleksei S. Suvorin, 1861-1881 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1972: ISBN 0-8143-1461-9), p. 172.

- ↑ Malamud, Bernard, ed. (1966). The Fixer. POCKET BOOKS, a Simon & Schuster division of GULF & WESTERN CORPORATION. ISBN 0-671-82568-2.

- ↑ German propaganda archive – Caricatures from Der Stürmer, Calvin College website.

- ↑ Bankier, David (2005-01-01). The Jews are Coming Back: The Return of the Jews to Their Countries of Origin After WW II. Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781571815279.

- ↑ Gerber, Gane S. (1986). "Anti-Semitism and the Muslim World". In Berger, David. History and hate: the dimensions of anti-Semitism. Philadelphia, PA: Jewish Publication Society. p. 88. ISBN 0-8276-0267-7. LCCN 86002995. OCLC 13327957.

- ↑ Frankel, Jonathan. The Damascus Affair: "Ritual Murder," Politics, and the Jews in 1840, pp. 418, 421. Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0-521-48396-4

- ↑ Goldberg, Jeffrey. Prisoners: A Story of Friendship and Terror. New York: Vintage, 2006. p. 250

- ↑ "Письмо пятисот. Вторая серия. Лучше не стало". Xeno.sova-center.ru. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- ↑ "Русская линия / Актуальные темы / "Письмо пятисот": Обращение в Генеральную прокуратуру представителей русской общественности с призывом запретить в России экстремистские еврейские организации". Rusk.ru. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- ↑ "The investigation of the murder of five schoolboys in Krasnoyarsk was extended again (Regnum, August 20, 2007)". Regnum.ru. 2007-08-20. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- ↑ ""Jewish people were accused with murder of children in Krasnoyarsk" ("Regnum", May 12, 2005)". Regnum.ru. 2005-05-16. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- ↑ "Russian nationalistic publishers "Russian Idea", the article about the antisemitic movement "Living Without the Fear of the Jews.", June 2007: "...the murder of five children in Krasnoyarsk, which bodies were bloodless. Our layer V. A. Solomatov said that there is undoubtedly a ritual murder..."". Rusidea.org. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- ↑ Hasids were accused in Krasnoyarsk children murder, the Beilis Affair was reanimated (Regnum, May 16, 2005)

- ↑ "Islamic Movement head charged with incitement to racism, violence", Haaretz, January 29, 2008.

- ↑ "Interview with two members of a Polish team of anthropologists, sociologists and one theologian researching the persistence of blood libel myths" Archived August 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Joanna Tokarska-Bakir, Sandomierz blood libel legends

- ↑ Joanna Tokarska-Bakir, Legendy o krwi, antropologia przesądu (Anthropology of Prejudice: Blood Libel Myths) Warsaw, WAB, 2008, 796 pp, 89 złotys, reviewed here by Jean-Yves Potel

- ↑ Egyptian extremists an ill wind in Arab Spring by Harry Sterling, Calgary Herald, September 2, 2011.

- ↑ Blood Libel on Hamas' Al-Aqsa TV – American Center for Islamic Research President Dr. Sallah Sultan: Jews Murder Non-Jews and Use Their Blood for Passover Matzos, MEMRI, Special Dispatch No. 2907, April 14, 2010.

- ↑ Blood Libel on Hamas TV - President of the American Center for Islamic Research Dr. Sallah Sultan: Jews Murder Non-Jews and Use Their Blood to Knead Passover Matzos, MEMRITV, clip no. 2443 – Transcript, March 31, 2010 (video clip available here).

- ↑ Islamic group invited anti-Semitic speaker Archived August 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., The Local (Sweden's News in English), March 25, 2011.

- ↑ Egypt: More Calls to Murder Israelis by Maayana Miskin, Arutz Sheva 7 (Isranelnationalnews.com), August 28, 2011.

- ↑ Why the Muslim Association doesn’t expresses reservations towards Antisemitism by Willie Silberstein, Coordination Forum for Countering Antisemitism (CFCA), April 17, 2011.

- ↑ Saudi Cleric Salman Al-Odeh: Jews Use Human Blood for Passover Matzos, MEMRITV, Clip No. 3536, (transcript), August 13, 2012.

- ↑ Saudi cleric accuses Jewish people of genocide, drinking human blood by Ilan Ben Zion, The Times of Israel, August 16, 2012.

- ↑ Palestinian non-profit belatedly apologizes for blood libel article Archived April 6, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Egyptian Politician Khaled Zaafrani: Jews Use Human Blood for Passover Matzos, MEMRITV, Clip No. 3873 (transcript), May 24, 2013 (see also: Video Clip).

- ↑ Egyptian Politician: Jews Use Human Blood for Passover Matzos by Elad Benari, Arutz Sheva, June 17, 2013.

- ↑ Egyptian politician revives Passover blood libel by Gavriel Fiske, Times of Israel, June 19, 2013.

- ↑ Egyptian Politician Smiles Giddily as He Pushes anti-Semitic Libel that Jews Use Blood of Christian Children for Passover Matzos by Sharona Schwartz, The Blaze, June 17, 2013.

- ↑ Top Hamas Official Osama Hamdan: Jews Use Blood for Passover Matzos, MEMRITV, Clip No. 4384 (transcript), July 28, 2014. (video clip available here)

- ↑ Blood libel: the myth that fuels anti-Semitism by Candida Moss and Joel Baden, special to CNN, August 6th, 2014.

- ↑ Friday Sermon by Former Jordanian Minister: Jews Use Children's Blood for Their Holiday Matzos, MEMRI Clip No. 4454 (transcript), August 22, 2014. (video clip available here).

- ↑ English translation here.

- ↑ As shown by David Kertzer in The Popes Against the Jews (New York, 2001), pp. 161–63.

- ↑ Pope Gregory X. "Medieval Sourcebook: Gregory X: Letter on Jews, (1271-76) - Against the Blood Libel". Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ↑ Gianfranco Miletto, "The Human Body as a Musical Instrument in the Sermons of Judah Moscato", in The Jewish Body: Corporeality, Society, and Identity in the Renaissance and Early Modern Period, edited by Giuseppe Veltri and Maria Diemling (Leiden, 2009), p. 384.

- ↑ Marina Caffiero, Forced Baptisms: Histories of Jews, Christians, and Converts in Papal Rome, translated by Lydia G. Cochrane (University of California Press, 2012), pp. 34-36.

- ↑ Mansel, Phillip (1998). Constantinople: City of the World's Desire, 1453–1924. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-312-18708-8.

- ↑ An Anti-Jewish Book Linked to Syrian Aide, New York Times, 15 July 1986.

- 1 2 "Literature Based on Mixed Sources - Classic Blood Libel: Mustafa Tlas' Matzah of Zion". ADL. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ↑ Blood Libel Judith Apter Klinghoffer, History News Network, 19 December 2006.

- ↑ Osama El-Baz. "Al-Ahram Weekly Online, January 2–8, 2003 (Issue No. 619)". Weekly.ahram.org.eg. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- ↑ Anti-Semitic Series airs on Arab Television, Anti Defamation League, January 9, 2004

- ↑ Clip from Ash-Shatat, MEMRI

- ↑ Blood Libel Alive and Well in the Muslim World, Arutz Sheva, March 25, 2013

Further reading

- E. M. Rose, The Murder of William of Norwich: The Origins of the Blood Libel in Medieval Europe (Oxford University Press, 2015)

- Darren O'Brien, The Pinnacle of Hatred the Blood Libel and the Jews, (The Vidal Sassoon International Center for the Study of Antisemitism, Hebrew University Magnes Press, Jerusalem, 2011).

- David Biale Blood and Belief (2007)

- Dundes, Alan (1991). The Blood Libel Legend: A Casebook in Anti-Semitic Folklore. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-13114-2.

- Jewish Encyclopedia article: (Richard Gottheil, Hermann L.Strack, Joseph Jacobs) Blood Accusation

- Leikin, Ezekiel. The Beilis Transcripts. The Anti-Semitic Trial that Shook the World. ISBN 0-87668-179-8

- R. Po-chia Hsia, "The Myth of Ritual Murder: Jews and Magic in Reformation Germany" (New Haven: Yale UP, 1988). ISBN 0-300-04120-9 (cloth), ISBN 0-300-04746-0 (pbk.).

- The Chaucer Review: Emmy Stark Zitter: Antisemitism in Chaúcer's Prioress's Tale

- Joanna Tokarska-Bakir, Legendy o krwi, antropologia przesądu (Anthropology of Prejudice: Blood Libel Myths) Warsaw, WAB, 2008, 796 pp, 89 złotys, reviewed here by Jean-Yves Potel

- Wesker, Arnold, Blood Libel in Wild Spring and Other Plays London, 1994.

- Paul Gensler: "Die Damaskusaffäre: Judeophobie in einer anonymen Damszener Chronik." Grin Verlag, 2011

External links

| Look up blood libel in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blood libel. |

- Urban Legends Reference Pages: Religion (Blood Feast)

- Example of anti-Semitic propaganda

- Resources > Medieval Jewish History > Blood Libels Jewish History Resource Center, Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- The Port Jews of Corfu and the 'Blood Libel' of 1891: A Tale of Many Centuries and of One Event Athanasios (Sakis) Gekas

- The Ritual Murder Libel and the Jew: The Report by Cardinal Lorenzo Ganganelli (Pope Clement XIV.) edited by Cecil Roth (1935)

- Raphael Langham William of Norwich The Jewish Historical Society of England

- The Life and Miracles of St William of Norwich by Thomas of Monmouth (edited by Augustus Jessopp DD)

- Antisemitic painting in Sandomierz Cathedral (17th century) Karol (Charles) de Prévôt; an Italian painter of French extraction

- The Jewish Virtual Library