Black Shuck

Black Shuck, Old Shuck, Old Shock or simply Shuck is the name given to a ghostly black dog which is said to roam the coastline and countryside of East Anglia. Accounts of the animal form part of the folklore of Norfolk, Suffolk, the Cambridgeshire fens and Essex.[2][3]

The name Shuck may derive from the Old English word scucca meaning "demon", or possibly from the local dialect word shucky meaning "shaggy" or "hairy".[4]

Black Shuck is one of many ghostly black dogs recorded across the British Isles.[5] Sometimes recorded as an omen of death, sometimes a more companionable animal, it is classified as a cryptid, and there are varying accounts of the animal's appearance.[4][6] Writing in 1877, Walter Rye stated that Shuck was "the most curious of our local apparitions, as they are no doubt varieties of the same animal.[7]

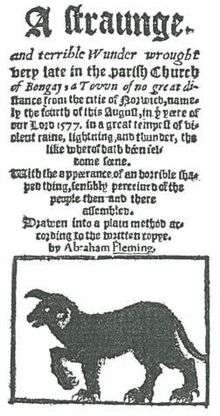

Its alleged appearance in 1577 at Bungay and Blythburgh is a particularly famous account of the beast, and images of black sinister dogs have become part of the iconography of the area and have appeared in popular culture.[1]

Folklore

For centuries, inhabitants of England have told tales of a large black dog with malevolent flaming eyes (or in some variants of the legend a single eye) that are red or alternatively green. They are described as being 'like saucers'. According to reports, the beast varies in size and stature from that of simply a large dog to being the size of a calf or even a horse.[1][6] Sometimes Black Shuck is recorded as having appeared headless, and at other times as floating on a carpet of mist.

According to folklore, the spectre haunts the landscapes of East Anglia, primarily coastline, graveyards, sideroads, crossroads, bodies of water and dark forests.[4] W. A. Dutt, in his 1901 Highways & Byways in East Anglia describes the creature thus:

He takes the form of a huge black dog, and prowls along dark lanes and lonesome field footpaths, where, although his howling makes the hearer's blood run cold, his footfalls make no sound. You may know him at once, should you see him, by his fiery eye; he has but one, and that, like the Cyclops', is in the middle of his head. But such an encounter might bring you the worst of luck: it is even said that to meet him is to be warned that your death will occur before the end of the year. So you will do well to shut your eyes if you hear him howling; shut them even if you are uncertain whether it is the dog fiend or the voice of the wind you hear. Should you never set eyes on our Norfolk Snarleyow you may perhaps doubt his existence, and, like other learned folks, tell us that his story is nothing but the old Scandinavian myth of the black hound of Odin, brought to us by the Vikings who long ago settled down on the Norfolk coast.[8]

It is Dutt's description which gave rise to one misnomer for Black Shuck as "Old Snarleyow"; in the context of his description it is a comparative to Frederick Marryat's 1837 novel Snarleyyow, or the Dog Fiend, which tells the tale of a troublesome ship's dog.[9]

According to some legends, the dog's appearance bodes ill to the beholder - for example in the Maldon and Dengie area of Essex, the most southerly point of sightings, where seeing Black Shuck means the observer's almost immediate death. However, more often than not, stories tell of Black Shuck terrifying his victims, but leaving them alone to continue living normal lives; in some cases it has supposedly happened before close relatives to the observer die or become ill.

By contrast, in other tales the animal is regarded as relatively benign and said to accompany women on their way home in the role of protector rather than a portent of ill omen.[10] Some black dogs have been said to help lost travellers find their way home and are more often helpful than threatening; Sherwood notes that benign accounts of the dog become more regular towards the end of the 19th and throughout the 20th centuries.[6]

Sightings

Appearance at Peterborough Abbey

Dr Simon Sherwood suggests that the earliest surviving description of devilish black hounds is an account of an incident in the Peterborough Abbey recorded in the Peterborough Chronicle (one version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle) around 1127:

Let no-one be surprised at the truth of what we are about to relate, for it was common knowledge throughout the whole country that immediately after [Abbot Henry of Poitou's arrival at Peterborough Abbey] - it was the Sunday when they sing Exurge Quare - many men both saw and heard a great number of huntsmen hunting. The huntsmen were black, huge and hideous, and rode on black horses and on black he-goats and the hounds were jet black with eyes like saucers and horrible. This was seen in the very deer park of the town of Peterborough and in all the woods that stretch from that same town to Stamford, and in the night the monks heard them sounding and winding their horns. Reliable witnesses who kept watch in the night declared that there might well have been as many as twenty or thirty of them winding their horns as near they could tell. This was seen and heard from the time of his arrival all through Lent and right up to Easter."[6][11]

This account also appears to describe the Europe-wide phenomenon of a Wild Hunt.

Appearance in Bungay and Blythburgh

One of the most notable reports of Black Shuck is of his appearance at the churches of Bungay and Blythburgh in Suffolk. On 4 August 1577, at Blythburgh, Black Shuck is said to have burst in through the doors of Holy Trinity Church to a clap of thunder. He ran up the nave, past a large congregation, killing a man and boy and causing the church steeple to collapse through the roof. As the dog left, he left scorch marks on the north door which can be seen at the church to this day.[12]

The encounter on the same day at St Mary's Church, Bungay was described in A Straunge and Terrible Wunder by the Reverend Abraham Fleming in 1577:

This black dog, or the divel in such a linenesse (God hee knoweth al who worketh all,) running all along down the body of the church with great swiftnesse, and incredible haste, among the people, in a visible fourm and shape, passed between two persons, as they were kneeling uppon their knees, and occupied in prayer as it seemed, wrung the necks of them bothe at one instant clene backward, in somuch that even at a mome[n]t where they kneeled, they stra[n]gely dyed.[13]

Adams was a clergyman from London, and therefore probably only published his account based on exaggerated oral accounts. Other local accounts attribute the event to the Devil (Abrahams calls the animal "the Divel in such a likeness"). The scorch marks on the door are referred to by the locals as "the devil’s fingerprints", and the event is remembered in this verse:

All down the church in midst of fire, the hellish monster flew, and, passing onward to the quire, he many people slew.[14]

Dr David Waldron and Christopher Reeve suggest that a fierce electrical storm recorded by contemporary accounts on that date, coupled with the trauma of the ongoing Reformation, may have led to the accounts entering folklore.[15]

Hauntings of Littleport

Littleport, Cambridgeshire is home to two different legends of spectral black dogs, which have been linked to the Black Shuck folklore, but differ in significant aspects: local folklorist W.H. Barrett relates the story of a huge black dog haunting the area after being killed rescuing a local girl from a lustful friar in pre-reformation times,[16][17] while fellow folklorist Enid Porter relates stories of a black dog haunting the A10 road after its owner drowned in the nearby River Great Ouse in the 1800s.[18][19]

Appearance between Dereham and Swanton Morley

John Harries reported that in November 1945 he was followed by a black dog, which kept pace with him at speeds up to 20 mph and stopped when he stopped, as he cycled from Dereham to RAF Swanton Morley, where it vanished.[4]

Possible Exhumation

In May 2014 a large dog was excavated at Leiston Abbey and was linked to the legend of Black Shuck.[20][21] Carbon dating of the bones "indicated a date of either 1650-1690, 1730-1810 or post 1920" and the animal "was likely to have been interred when there was no surface trace of the original building remaining".[22] East Anglian poet and songwriter, Martin Newell, wrote about the discovery and retold some of the stories he heard from locals while preparing his epic poem, Black Shuck: The Ghost Dog of Eastern England:

The odd thing is that people today still claim sightings of Black Dog. While researching my own project, I was surprised at how seriously the story was taken, especially in the north of the region. “Ah, you’re writing about that now, are you?” a Norfolk shopkeeper asked me. “Well, be careful.”

One local woman told me that she’d seen Black Shuck early one summer morning in the 1950s, near Cromer, when returning from a dance. A Suffolk man said he’d seen the dog one evening on the marshes near Felixstowe. I later read an old newspaper story of an encounter in Essex. The account was given of a midwife who had been cycling home after a delivery during the 1930s. One winter’s night, she claimed, she was followed by the creature through the lanes near Tolleshunt Darcy. She added that the dog was huge and no matter how fast she pedalled it seemed to effortlessly keep up with her. The apparition, which remained silent throughout, then suddenly vanished.[23][24]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Jennifer Westwood and Jacqueline Simpson, The Lore of the Land: A Guide to England's Legends, from Spring-heeled Jack to the Witches of Warboys, Penguin, 2005, pp.687-688

- ↑ Jennifer Westwood, Jacqueline Simpson, Sophia Kingshill, The Penguin Book of Ghosts, Penguin, 2008

- ↑ Enid Porter, Cambridgeshire customs and folklore: with Fenland material provided, Taylor & Francis, 1969, p.53

- 1 2 3 4 George M. Eberhart, Mysterious Creatures: A Guide to Cryptozoology: Volume 1, 2002, p. 63

- ↑ Country Life: Volume 174, 1983

- 1 2 3 4 Dr Simon Sherwood, Apparitions of Black Dogs, University of Northampton Psychology Department, 2008

- ↑ Walter Rye, The Norfolk antiquarian miscellany, Miller and Leavins, 1877

- ↑ W. A. Dutt: Highways & Byways in East Anglia, MacMillan, 1901, p.216

- ↑ Mike Burgess, Moddey Dhoo & Snarleyow, Hidden East Anglia, 2005

- ↑ "The Tollesbury Midwife".

- ↑ G McEwan, Mystery Animals of Britain and Ireland, Robert Hale 1986, 122

- ↑ John Seymour, The companion guide to East Anglia, Collins, 1977

- ↑ Abraham Adams, A strange, and terrible wunder, London 1577, reprinted 1948

- ↑ Enid Porter, The folklore of East Anglia, Volume 1974, Part 2

- ↑ Dr. David Waldron and Christopher Reeve, Shock! The Black Dog of Bungay: A Case Study in Folklore, Hidden Design Ltd, 2010

- ↑ Barrett, Walter Henry (1963), Porter, Enid, ed., Tales from the Fens, Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 9780710010544

- ↑ James, Maureen (2014), "Of Strange Phenomena: Black Dogs, Will o' the Wykes and Lantern Men", Cambridgeshire Folk Tales, History Press, ISBN 9780752466286

- ↑ Porter, Enid (1969), Cambridgeshire Customs & Folklore, Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 9780710062017

- ↑ Codd, Daniel (2010), "The Weird Animal Kingdom: Black Shuck and Other Phantom Animals", Mysterious Cambridgeshire, JMD Media, ISBN 9781859838082

- ↑ "Leiston: Are these the bones of devil dog, Black Shuck?". East Anglian Daily Times.

- ↑ "Bones of 7ft Hound from Hell Black Shuck 'Discovered in Suffolk Countryside'". International Business Times UK.

- ↑ "Feature LA_701 Leiston Abbey". Digventures.com. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ↑ "Black Shuck". www.jardinepress.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-11-05.

- ↑ Newell, Martin (6/9/2014). "Martin Newell's Joy of Essex: Black Shuck is the hell-hound legend that won't lie down". East Anglian Daily Times. Archant Community Media Ltd. Retrieved 11/4/2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help)