Bill Richmond

| Bill Richmond | |

|---|---|

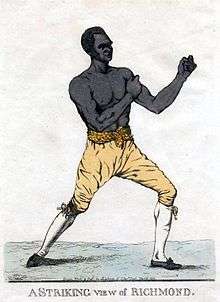

1810 depiction of Richmond | |

| Statistics | |

| Nickname(s) | The Black Terror |

| Rated at | Welterweight |

| Nationality | American |

| Born |

August 5, 1763 Cuckold's Town, New York |

| Died |

December 28, 1829 (aged 66) London, England, UK |

| Boxing record | |

| Total fights | 19 |

| Wins | 17 |

| Wins by KO | N/A |

| Losses | 2 |

| Draws | 0 |

| No contests | 0 |

Bill Richmond (August 5, 1763 – December 28, 1829) was an African-American boxer, born a slave in Richmondtown), Staten Island, New York. Although born in America, Richmond lived for the majority of his life in England, where all his boxing contests took place.

During the American Revolutionary War, Richmond, whose slave owner was the Reverend Richard Charlton, entered the service of Hugh Percy, later the second Duke of Northumberland, who took him to England in 1777.

Some historians have claimed that on September 22, 1776, Richmond was the one of the hangmen who executed Nathan Hale.[1] However, Luke G. Williams, in his biography of Richmond, entitled Richmond Unchained, claims that the Richmond who served as the hangman of Hale was not Bill Richmond, but another man of the same surname. Williams writes that: "The Richmond as hangman theory took root due to a coalescence of circumstantial evidence: numerous accounts of Hale’s execution feature references to a black or mulatto hangman named Richmond (for example, the 1856 book Life of Nathan Hale: The Martyr Spy of the American Revolution, refers to the ‘negro Richmond, the common hangman’); artwork of the execution published by Harpers Weekly in 1860 shows a black man holding the hanging rope; and then there is Richmond’s connection to Percy and the British military, as well as the proximity of Staten Island to the site of Hale’s execution in Manhattan. Given this series of coincidences, it seems a reasonable enough piece of speculation. However several hitherto ignored sources from the eighteenth century directly contradict the possibility of Richmond being involved. Quite simply, Hale’s hangman may have been black and named Richmond, but he wasn’t Bill Richmond. Rather, as reports in the Gaines Mercury and Royal Gazette indicate, he was a Pennsylvania runaway with the same surname as Bill who ended up working as the hangman for the notorious Boston Provost Marshal William Cunningham. The hangman Richmond absconded from his duties in 1781, Cunningham offering a one-guinea reward for his return a full four years after Bill Richmond’s likely departure for England." [2]

After arriving in England, Percy paid for Richmond to be educated and then apprenticed him to a cabinetmaker in York. At some stage in the early 1790s Richmond married a local white woman in Yorkshire, most likely one Mary Dunwick, in a marriage recorded in Wakefield on 29 June 1791. Richmond and his wife would go on to have several children. According to boxing writer Pierce Egan, the well-dressed, literate and self-confident Richmond was an inevitable target for race hatred during his time in Yorkshire. Egan described several occasions when Richmond became embroiled in brawls after being insulted, once after he was labeled a ‘black devil’ for being in the company of a white woman - probably a reference to Mary. According to Egan, Richmond fought and won five boxing matches during this time, defeating George 'Dockey' Moore, two unnamed soldiers, one unnamed blacksmith and Frank Myers.

By 1795, Richmond and his family had moved to London, where he was employed by Thomas Pitt, 2nd Baron Camelford, a British peer and naval officer who was renowned for his unstable and erratic behaviour. Richmond was a member of Camelford's household and possibly also gave Camelford boxing and gymnastic instruction. Several times Richmond visited prize-fights in Camelford’s company and on 23 January 1804 he issued an impromptu challenge to experienced boxer George Maddox after Maddox had defeated another opponent. The seasoned Maddox was not the sort of boxer a novice should face in his first major contest, though, and Richmond was defeated in nine rounds.

After Camelford’s death in a duel on 11 March 1804, Richmond returned to boxing. Having discovered an aptitude for teaching, he began training and seconding other fighters and was soon a regular attendee at the Fives Court, London’s leading pugilistic exhibition venue in St Martin's Street.

By 1805 Richmond was on the comeback trail, defeating Jewish boxer Youssop and vanquishing contender Jack Holmes to secure a contest against highly touted Tom Cribb. Unfortunately, Cribb and Richmond’s counter-punching styles resulted in a dull bout which Cribb won, leaving Richmond in tears. The contest solidified a grudge between the two men which would last years. Richmond didn’t box again until 1808, when several quick wins helped him land a dream fight - a rematch with Maddox. The contest, in August 1809, demonstrated Richmond’s mastery of ‘boxing on the retreat’. He battered Maddox mercilessly, earning the admiration of spectator William Windham, MP, who argued the skill and bravery on show were as impressive as that displayed by British troops in their triumph at the Battle of Talavera.

Richmond’s winnings enabled him to become landlord of the Horse and Dolphin pub near Leicester Square. It was here that he probably met Tom Molineaux, another former slave. Richmond immediately discerned Molineaux’s pugilistic potential and put his own boxing career to one side to train him, with a view to a challenge against Cribb, who was now champion.

Under Richmond’s tutelage, Molineaux demolished two contenders before squaring up to Cribb at Copthall Common in December 1810. It was an epic contest, and one of the most controversial bouts in boxing history - Cribb won, barely, amid the chaos of a ring invasion and whisperings of a long count that had allowed the champion longer than the allowable 30 seconds to recover in between rounds. Molineaux, many maintained, had been cheated.

Historians disagree about whether the alleged bias shown to Cribb was motivated by racism, nationalism or fears on the part of Cribb backers that they would lose their wagers. Certainly, before the fight there was nervousness about the prospect of a Molineaux victory, with the Chester Chronicle claiming that “many of the noble patronizers [sic.] of this accomplished art, begin to be alarmed, lest, to the eternal dishonour of our country, a negro should become the Champion of England!”

A rematch was inevitable, but by the time it happened, in October 1811, Molineaux was past his best. Cribb won with relative ease and Richmond and Molineaux’s relationship was promptly severed. Having lost money brokering and betting on the fight, Richmond had to give up the Horse and Dolphin and rebuild. He became a member of the Pugilistic Club (‘PC’), the sport’s first ‘governing body’, and returned to the ring against Jack Davis in May 1814, despite the fact he was now fifty years old.

A handsome victory against Davis encouraged Richmond to accept his riskiest challenge yet - a contest against Tom Shelton, a fancied contender around half his age. After suffering a horrendous eye injury early on, Richmond wore Shelton down after twenty-three pulsating rounds, leaping over the ropes with joy to celebrate the defining moment of his career. “Impetuous men must not fight Richmond,” Egan declared, “as in his hands they become victims to their own temerity … The older he grows, the better pugilist he proves himself … He is an extraordinary man.”

Such achievements warranted a title shot, but with Cribb inactive, Richmond opted for retirement instead. His position among England’s leading pugilists was assured; he twice exhibited his skills for visiting European royalty and was among the most respected and admired of pugilistic trainers and instructors. Even more remarkably, Richmond was one of the pugilists selected to act as an usher at the coronation of George IV in 1821, earning a letter of thanks from Lord Gwydyr and the Home Secretary Lord Sidmouth. For a black man to be given such a role at an event symbolic of white privilege was astonishing, particularly considering slavery wasn’t outlawed in the British Empire until 1833.

Touchingly, Richmond’s former rival Cribb became a close friend in the last years of his life, the two men often conversing late into the night at Cribb’s pub, the Union Arms on Panton Street. It was here that Richmond spent his last evening, before he died aged 66 in December 1829.

Further reading

Luke G. Williams, Richmond Unchained (Amberley, 2015)

See also

References

- ↑ "A CHRONOLOGY OF AFRICAN AMERICAN MILITARY SERVICE". Integration of the Armed Forces. Redstone Arsenal Historical Information. Archived from the original on March 1, 2007. Retrieved February 9, 2007.

- ↑ Williams, Luke G., Richmond Unchained, Amberley, 2015; Gaines Mercury, 4 August 1781 & Royal Gazette, 4 August 1781