"Wild Bill" Hickok

| "Wild Bill" Hickok | |

|---|---|

James Butler "Wild Bill" Hickok, photograph date unknown | |

| Born |

James Butler Hickok May 27, 1837 Homer, LaSalle County, Illinois (present-day Troy Grove) |

| Died |

August 2, 1876 (aged 39) Deadwood, Lawrence County, Dakota Territory (present-day Deadwood, South Dakota) |

| Cause of death | Murder by shooting |

| Resting place | Mount Moriah Cemetery, Deadwood, Dakota Territory |

| Other names | James B. Hickok, J.B. Hickok, Duck Bill, Shanghai Bill, William Hickok, William Haycock |

| Occupation | farmer, vigilante, drover, teamster, wagon master, stagecoach driver, soldier, spy, scout, detective, lawman, gunfighter, gambler, showman, performer, actor |

| Parent(s) | William Alonzo Hickok and Polly Butler |

| Signature | |

|

| |

James Butler "Wild Bill" Hickok (May 27, 1837 – August 2, 1876), also "J.B. Hickok" for his signature name, was a folk hero of the American Old West, known for his work across the frontier as a drover, wagon master, soldier, spy, scout, lawman, gunfighter, gambler, showman, and actor. He earned a great deal of notoriety in his own time, much of it bolstered by the many outlandish, often fabricated, tales he told about his life. Some contemporary reports of his exploits are known to be fictitious but, along with his own stories, remain the basis for much of his fame and reputation.

Hickok was born and raised on a farm in northern Illinois, at a time when lawlessness and vigilante activity was rampant because of the influence of the "Banditti of the Prairie". Hickok was drawn to this ruffian lifestyle and headed west, at age 18, as a fugitive from justice, working as a stagecoach driver and later as a lawman in the frontier territories of Kansas and Nebraska. He fought and spied for the Union Army during the American Civil War and gained publicity after the war as a scout, marksman, actor, and professional gambler. Over the course of his life, he was involved in several notable shootouts.

In 1876, Hickok was shot from behind and killed while playing poker in a saloon in Deadwood, Dakota Territory (present-day South Dakota), by Jack McCall, an unsuccessful gambler. The hand of cards which he supposedly held at the time of his death (including the ace of spades, the ace of clubs, the eight of spades, and the eight of clubs) has become known as the dead man's hand.

Hickok remains a popular figure in frontier history. Many historic sites and monuments commemorate his life, and he has been depicted numerous times in literature, film, and television. He is chiefly portrayed as a protagonist, though historical accounts of his actions are often controversial.

Early life

James Butler Hickok was born May 27, 1837, in Homer, Illinois (present-day Troy Grove, Illinois) to William Alonzo Hickok, a farmer and abolitionist, and his wife, Polly Butler.[1] His father was said to have used the family house, now demolished, as a station on the Underground Railroad. He was the fourth of six children. William Hickok died in 1852, when James was 15.[2] Hickok was a good shot from a young age and was recognized locally as an outstanding marksman with a pistol.[3] Photographs of Hickok depict dark hair, and all contemporaneous descriptions confirm that he had red hair.[4]

In 1855, at age 18, James Hickok fled Illinois following a fight with Charles Hudson, during which both fell into a canal (each thought, mistakenly, that he had killed the other). Hickok moved to Leavenworth in the Kansas Territory, where he joined "General" Jim Lane's Free State Army (also known as the Jayhawkers), a vigilante group active in the new territory.[5] While a Jayhawker, he met 12-year-old William Cody (later known as Buffalo Bill), who despite his age was a scout for the U.S. Army during the Utah War.[6]

Nicknames

While in Nebraska, James Hickok was derisively referred to as "Duck Bill".[7] He grew a moustache following the McCanles incident and in 1861 began calling himself Wild Bill.[8][9] He was also known before 1861 by Jayhawkers as "Shanghai Bill" because of his height and slim build.[10]

James B. Hickok used the name William Hickok from 1858 and William Haycock during the Civil War. He was arrested while using the name Haycock in 1865. He afterward resumed using his given name, James Hickok. Most newspapers referred to him as William Haycock until 1869. Military records after 1865 list him as Hickok but note that he was also known as Haycock.[11][12]

Early career

Mauled by a bear

In 1857, Hickok claimed a 160-acre (65-ha) tract in Johnson County, Kansas (near present-day Lenexa).[13] On March 22, 1858, he was elected one of the first four constables of Monticello Township. In 1859, he joined the Russell, Waddell & Majors freight company, the parent company of the Pony Express.

In 1860, he was badly injured by a bear while driving a freight team from Independence, Missouri to Santa Fe, New Mexico. According to Hickok's account, he found the road blocked by a cinnamon bear and its two cubs. Dismounting, he approached the bear and fired a shot into its head, but the bullet ricocheted from its skull, infuriating it. The bear attacked, crushing Hickok with its body. Hickok managed to fire another shot, disabling the bear's paw. The bear then grabbed his arm in its mouth, but Hickok was able to grab his knife and slash its throat, killing it.

Hickok was severely injured, with a crushed chest, shoulder and arm. He was bedridden for four months before being sent to Rock Creek Station in the Nebraska Territory to work as a stable hand while he recovered. The freight company had built the stagecoach stop along the Oregon Trail near Fairbury, Nebraska, on land purchased from David McCanles.[14]

McCanles shooting

On July 12, 1861, McCanles went to the Rock Creek Station office to demand an overdue property payment from Horace Wellman, the station manager. McCanles reportedly threatened Wellman, and either Hickok (who was hiding behind a curtain) or Wellman killed him.[15][16] Hickok, Wellman, and another employee, J.W. Brink, were tried for killing McCanles but were found to have acted in self-defense. McCanles may have been the first man Hickok killed.[15]

Civil War service

After the Civil War broke out in April 1861, James Hickok became a teamster for the Union Army in Sedalia, Missouri. By the end of 1861, he was a wagonmaster, but in September 1862 he was discharged for unknown reasons. He then joined General James Henry Lane's Kansas Brigade and, while serving with the brigade, saw his friend Buffalo Bill Cody, who was serving as a scout. There are no records of Hickok's whereabouts for the next year, although at least one source claims that he was a Union spy in Confederate territory during this time.[17]

In late 1863 he worked for the provost marshal of southwest Missouri as a member of the Springfield detective police. His work included identifying and counting the number of troops in uniform who were drinking while on duty, verifying hotel liquor licenses, and tracking down individuals who owed money to the cash-strapped Union Army.

In 1864, Hickok had not been paid for some time and was hired as a scout by General John B. Sanborn. In June 1865, Hickok mustered out and went to Springfield, where he gambled.[17] The 1883 History of Greene County, Missouri described him as "by nature a ruffian... a drunken, swaggering fellow, who delighted when 'on a spree' to frighten nervous men and timid women."[18]

Professional life

Duel with Davis Tutt

While in Springfield, Hickok and a local gambler named Davis Tutt had several disagreements over unpaid gambling debts and their mutual affection for the same women. Tutt stole a watch belonging to Hickok, who demanded that Tutt return it. They initially agreed not to fight over the watch, but when Hickok saw Tutt wearing it, he warned him to stay away. On July 21, 1865, the two men faced off in Springfield's town square, standing sideways before drawing and firing their weapons. Their quick-draw duel was recorded as the first of its kind.[19] Tutt's shot missed, but Hickok's struck Tutt through the heart from about 75 yards (69 m) away. Tutt called out, "Boys, I'm killed" before he collapsed and died.[20]

Two days later, Hickok was arrested for murder. The charge was later reduced to manslaughter. He was released on $2,000 bail and stood trial on August 3, 1865. At the end of the trial, Judge Sempronius H. Boyd gave the jury contradictory instructions. He first instructed the jury that a conviction was its only option under the law.[notes 1] He then instructed them that they could apply the unwritten law of the "fair fight" and acquit.[notes 2] The jury voted to acquit Hickok, resulting in public backlash and criticism of the verdict.[21]

Several weeks later, Hickok was interviewed by Colonel George Ward Nichols. The interview was published in Harper's New Monthly Magazine. Under the name "Wild Bill Hitchcock" [sic], the article recounted the "hundreds" of men whom Hickok had personally killed and other exaggerated exploits. The article was controversial wherever Hickok was known, and several frontier newspapers wrote rebuttals.[notes 3]

Deputy U.S. Marshal in Kansas

In September 1865, Hickok came in second in the election for city marshal of Springfield. Leaving Springfield, he was recommended for the position of Deputy United States Marshal at Fort Riley, Kansas. This was during the Indian wars, in which Hickok sometimes served as a scout for General George A. Custer's 7th Cavalry.[6]

In 1865, Hickok recruited six Indians to accompany him to Niagara Falls, where he put on an outdoor demonstration called The Daring Buffalo Chasers of the Plains.[2] Since the event was outdoors, he could not compel people to pay, and the venture was a financial failure.[22]:34

Killings of Native Americans

Hickok was reported to be "an inveterate hater of Indians", but it is difficult to separate fact from fiction. Witnesses confirm that while working as a scout at Fort Harker, Kansas, on May 11, 1867, he was attacked by a large group of Indians, who fled after he shot and killed two. In July, Hickok told a newspaper reporter that he had led several soldiers in pursuit of Indians who had killed four men near the fort on July 2. He reported returning with five prisoners after killing ten. Witnesses confirm that the story was true in part: the party did set out to find those who had killed the four men,[notes 4] but the group returned to the fort "without nary a dead Indian, [never] even seeing a live one".[23][24]

Shootout in Nebraska

In 1867, Hickok reportedly was involved in a dispute with drunken cowboys inside a saloon in Jefferson County, Nebraska. One of them pushed him, causing him to drop his drink. Hickok struck the man, and four of his friends rose with guns drawn. Hickok persuaded the men to step outside where he faced all four at 15 feet (4.6 m). The bartender counted down and Hickok killed three of the men with a bullet to the head and wounded the fourth. Hickok was wounded in the shoulder.[22]:40–43

Later that year, he moved to Kansas, where he ran for sheriff in Ellsworth County on November 5, 1867. He was defeated by a former soldier, E.W. Kingsbury.

Move to Hays, Kansas

In December 1867, newspapers reported that Hickok had come to stay in Hays City, Kansas. He became a Deputy U.S. Marshal, and on March 28, 1868, he picked up eleven Union Army deserters who had been charged with stealing government property. Hickok was assigned to bring the men to Topeka for trial, and he requested a military escort from Fort Hays. He was assigned William F. Cody, a sergeant, and five privates. They arrived in Topeka on April 2.

Hickok remained in Hays through August 1868, when he brought 200 Cheyenne Indians to Hays to be viewed by "excursionists".[25]

Work as a scout

On September 1, Hickok was in Lincoln County, Kansas, where he was hired as a scout by the 10th Cavalry Regiment, a segregated African-American unit. On September 4, Hickok was wounded in the foot while rescuing several cattlemen in the Bijou Creek Basin who had been surrounded by Indians. The 10th Regiment arrived at Fort Lyon in Colorado in October and remained there for the rest of 1868.[25]

Marshal of Hays, Kansas

In July 1869, Hickok returned to Hays and was elected city marshal of Hays and sheriff of Ellis County, Kansas, in a special election held on August 23, 1869.[26] Three sheriffs had quit during the previous 18 months. Hickok may have been acting sheriff before he was elected; a newspaper reported that he arrested offenders on August 18, and the commander of Fort Hays wrote a letter to the assistant adjutant general on August 21 in which he praised Hickok for his work in apprehending deserters.[notes 5]

The regular county election was held on November 2, 1869, and Hickok, running as an independent, lost to his deputy, Peter Lanihan, running as a Democrat, but Hickok and Lanihan remained sheriff and deputy, respectively. Hickok accused a J.V. Macintosh of irregularities and misconduct during the election. On December 9, Hickok and Lanihan both served legal papers on Macintosh, and local newspapers acknowledged that Hickok had guardianship of Hays City.[27]:196

Killings as sheriff

In September 1869, his first month as sheriff, Hickok killed two men.

The first was Bill Mulvey, who was rampaging through town, drunk, shooting out mirrors and whisky bottles behind bars. Citizens warned Mulvey to behave, because Hickok was sheriff. Mulvey angrily declared that he had come to town to kill Hickok. When he saw Hickok, he leveled his cocked rifle at him. Hickok waved his hand past Mulvey at some onlookers and yelled, "Don't shoot him in the back; he is drunk." Mulvey wheeled his horse around to face those who might shoot him from behind, and before he realized he had been fooled, Hickok shot him through the temple.[6][28]

The second killed by James B. Hickok was Samuel Strawhun, a cowboy, who was causing a disturbance at 1 a.m. in a saloon on September 27 when Hickok and Lanihan went to the scene.[29] Strawhun "made remarks against Hickok", and Hickok killed him with a shot through the head. Hickok said he had "tried to restore order". At the coroner's inquest into Strawhun's death, despite "very contradictory" evidence from witnesses, the jury found the shooting justifiable.[27]:192

On July 17, 1870, James Hickok was attacked by two troopers from the 7th U.S. Cavalry, Jeremiah Lonergan and John Kyle (sometimes spelled Kile), in a saloon. Lonergan pinned Hickok to the ground, and Kyle put his gun to Hickok's ear. When Kyle's weapon misfired, Hickok shot Lonergan, wounding him in the knee, and shot Kyle twice, killing him.[notes 6] Hickok wasn't reelected to office.

Marshal of Abilene, Kansas

On April 15, 1871, Hickok became marshal of Abilene, Kansas. He replaced Marshal Tom "Bear River" Smith, who had been killed on November 2, 1870.[30]

The outlaw John Wesley Hardin arrived in Abilene at the end of a cattle drive in early 1871. Hardin was a well-known gunfighter and is known to have killed more than 27 men.[31] In his 1895 autobiography, published after his death, Hardin claimed to have been befriended by Hickok, the newly elected town marshal, after he had disarmed the marshal using the road agent's spin.[32] However, Hardin was known to exaggerate.[32] In any case, Hardin appeared to have thought highly of Hickok.[33]

James B. Hickok later said he did not know that "Wesley Clemmons" was Hardin's alias and that he was a wanted outlaw. He told Clemmons (Hardin) to stay out of trouble in Abilene and asked him to hand over his guns and Hardin complied.[34] Hardin claimed that when his cousin, Mannen Clements, was jailed for killing two cowhands, he persuaded Hickok to arrange for his escape.[35]

In August 1871, "Wild Bill" Hickok sought to arrest Hardin for killing Charles Couger in an Abilene hotel "for snoring too loud". Hardin left Kansas before Hickok could arrest him.

Shootout with Phil Coe

J.B. Hickok and Phil Coe, a saloon owner and acquaintance of Hardin's, had a dispute that resulted in a shootout. The Bull's Head Tavern in Abilene had been established by the gambler Ben Thompson and Coe, his partner, businessman and fellow gambler. The two entrepreneurs had painted a picture of a bull with a large erect penis on the side of their establishment as an advertisement. Citizens of the town complained to Hickok, who requested that Thompson and Coe remove the bull. They refused, so Hickok altered it himself. Infuriated, Thompson tried to incite John Wesley Hardin to kill Hickok, by exclaiming to Hardin that "He's a damn Yankee. Picks on rebels, especially Texans, to kill." Hardin was in town under his assumed name Wesley Clemmons but was better known to the townspeople by the alias Little Arkansas. He seemed to have respect for Hickok's abilities and replied, "If Bill needs killing why don't you kill him yourself?"[36] Hoping to intimidate Hickok, Coe allegedly stated that he could "kill a crow on the wing". Hickok's retort is one of the West's most famous sayings (though possibly apocryphal): "Did the crow have a pistol? Was he shooting back? I will be."

On October 5, 1871, "Wild Bill" Hickok was standing off a crowd during a street brawl, during which time Coe fired two shots. Hickok ordered him to be arrested for firing a pistol within the city limits. Coe claimed that he was shooting at a stray dog but suddenly turned his gun on Hickok, who fired first and killed Coe.[37] Hickok caught a glimpse of someone running toward him and quickly fired two more shots in reaction, accidentally shooting and killing Abilene Special Deputy Marshal Mike Williams, who was coming to his aid.[38] This event haunted Hickok for the remainder of his life.[39] There is another account of the Coe shootout: Theophilus Little, the mayor of Abilene and owner of the town's lumber yard, recorded his time in Abilene by writing in a notebook which was ultimately given to the Abilene Historical Society. Writing in 1911, he detailed his admiration of Hickok and included a paragraph on the shooting that differs considerably from the reported account:

"Phil" Coe was from Texas, ran the "Bull’s Head" a saloon and gambling den, sold whiskey and men’s souls. As vile a character as I ever met for some cause Wild Bill incurred Coe’s hatred and he vowed to secure the death of the Marshall. Not having the courage to do it himself, he one day filled about 200 cowboys with whiskey intending to get them into trouble with Wild Bill, hoping that they would get to shooting and in the melee shoot the marshal. But Coe "reckoned without his host". Wild Bill had learned of the scheme and cornered Coe, had his two pistols drawn on Coe. Just as he pulled the trigger one of the policemen rushed around the corner between Coe and the pistols and both balls entered his body, killing him instantly. In an instant, he pulled the triggers again sending two bullets into Coe's abdomen (Coe lived a day or two) and whirling with his two guns drawn on the drunken crowd of cowboys, "and now do any of you fellows want the rest of these bullets?" Not a word was uttered.[40]

Hickok was relieved of his duties as marshal less than two months after accidentally killing Deputy Williams, this incident being only one of a series of questionable shootings and claims of misconduct.[3]

Later life

In 1873, Buffalo Bill Cody and Texas Jack Omohundro invited Hickok to join them in a new play, Scouts of the Plains, after their earlier success.[41] Hickok and Texas Jack eventually left the show before Cody formed his Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show in 1882.[42]

In 1876, James B. Hickok was diagnosed by a doctor in Kansas City, Missouri with glaucoma and ophthalmia. His marksmanship and health were apparently in decline, as he had been arrested several times for vagrancy,[43] despite earning a good income from gambling and displays of showmanship only a few years earlier.

On March 5, 1876, J.B. Hickok married Agnes Thatcher Lake, a 50-year-old circus proprietor in Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory. Hickok left his new bride a few months later, joining Charlie Utter's wagon train to seek his fortune in the gold fields of South Dakota.[6] Martha Jane Cannary, known popularly as Calamity Jane, claimed in her autobiography that she was married to Hickok and had divorced him so he could be free to marry Agnes Lake, but no records have been found that support her account.[44] The two were believed to have met for the first time after Jane was released from the guardhouse in Fort Laramie and joined the wagon train in which Hickok was traveling. The wagon train arrived in Deadwood in July 1876.[45] Jane confirmed this account in an 1896 newspaper interview, although she claimed she had been hospitalized with illness rather than in the guardhouse.

Shortly before "Wild Bill" Hickok's death, he wrote a letter to his new wife, which read in part, "Agnes Darling, if such should be we never meet again, while firing my last shot, I will gently breathe the name of my wife—Agnes—and with wishes even for my enemies I will make the plunge and try to swim to the other shore."[46]

Death

On August 1, 1876, Hickok was playing poker at Nuttal & Mann's Saloon in Deadwood, Dakota Territory. When a seat opened up at the table, a drunk man named Jack McCall sat down to play. McCall lost heavily. Hickok encouraged McCall to quit the game until he could cover his losses and offered to give him money for breakfast. Though McCall accepted the money, he was apparently insulted.[47] The next day, Hickok was playing poker again. He usually sat with his back to a wall so he could see the entrance, but the only seat available when he joined the game was a chair facing away from the door. He asked another man at the table, Charles Rich, to change seats with him twice, but Rich refused.[48]

McCall entered the saloon, walked up behind James Butler Hickok, drew his 18-inch Sharps Improved revolver and shouted, "Damn you! Take that!" He shot Hickok in the back of the head at point-blank range.[49] Hickok died instantly. The bullet emerged through Hickok's right cheek and struck another player, riverboat Captain William Massie, in the left wrist.[50][51] Hickok may have told his friend Charlie Utter and others who were traveling with them that he thought he would be killed while in Deadwood.[52]

Jack McCall's two trials

McCall's motive for killing Hickok is the subject of speculation, largely concerning McCall's anger at Hickok giving him money for breakfast the day before, after McCall had lost heavily.[53][54]

Jack McCall was summoned before an informal "miners jury" (an ad hoc local group of miners and businessmen). McCall claimed he was avenging Hickok's earlier slaying of his brother, which may have been true. A man named Lew McCall was killed by an unknown lawman in Abilene, Kansas, but it is not known if the two men were related.[54] McCall was acquitted of the murder. The acquittal prompted editorializing in the Black Hills Pioneer: "Should it ever be our misfortune to kill a man ... we would simply ask that our trial may take place in some of the mining camps of these hills." Calamity Jane was reputed to have led a mob that threatened McCall with lynching, but at the time of Hickok’s death, Jane was being held by military authorities.[55] McCall left the area soon after and headed into Wyoming.

After bragging about killing Hickok, McCall was re-arrested. The second trial was not considered double jeopardy because of the irregular jury in the first trial and because Deadwood was in Indian country. The new trial was held in Yankton, the capital of the Dakota Territory. Hickok's brother, Lorenzo Butler, traveled from Illinois to attend the retrial. McCall was found guilty and sentenced to death. Leander Richardson, a reporter, interviewed McCall shortly before his death and wrote an article about him for the April 1877 issue of Scribner's Monthly. Butler spoke with McCall after the trial and said he showed no remorse.[56]

As I write the closing lines of this brief sketch, word reaches me that the slayer of Wild Bill has been rearrested by the United State authorities, and after trial has been sentenced to death for willful murder. He is now at Yankton, D.T. awaiting execution. At the [second] trial it was suggested that [McCall] was hired to do his work by gamblers who feared the time when better citizens should appoint Bill the champion of law and order – a post which he formerly sustained in Kansas border life, with credit to his manhood and his courage.[notes 7][56]

Jack McCall was hanged on March 1, 1877, and buried in a Roman Catholic cemetery. The cemetery was moved in 1881, and when his body was exhumed, the noose was found still around his neck.[57]

Hickok's dead man's hand

"Wild Bill" Hickok was playing five-card draw when he was shot. He was holding two pairs, black aces and black eights. The fifth card had been discarded, and its replacement had possibly not been dealt. The identity of the fifth card is the subject of debate.[notes 8]

Burial

Charlie Utter, Hickok's friend and companion, claimed Hickok's body and placed a notice in the local newspaper, the Black Hills Pioneer, which read:

Died in Deadwood, Black Hills, August 2, 1876, from the effects of a pistol shot, J. B. Hickock [sic] (Wild Bill) formerly of Cheyenne, Wyoming. Funeral services will be held at Charlie Utter's Camp, on Thursday afternoon, August 3, 1876, at 3 o'clock P. M. All are respectfully invited to attend.

Almost the entire town attended the funeral, and Utter had Hickok buried with a wooden grave marker reading:

Wild Bill, J. B. Hickock [sic] killed by the assassin Jack McCall in Deadwood, Black Hills, August 2, 1876. Pard, we will meet again in the happy hunting ground to part no more. Good bye, Colorado Charlie, C. H. Utter.

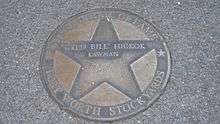

Hickok is known to have fatally shot six men and is suspected of having killed a seventh (McCanles). Despite his reputation,[58] Hickok was buried in the Ingelside Cemetery, Deadwood's original graveyard. This cemetery filled quickly, and in 1879, on the third anniversary of his original burial, Utter paid to move Hickok's remains to the new Mount Moriah Cemetery.[notes 9] Utter supervised the move and noted that, while perfectly preserved, Hickok had been imperfectly embalmed. As a result, calcium carbonate from the surrounding soil had replaced the flesh, leading to petrifaction. One of the workers, Joseph McLintock, wrote a detailed description of the re-interment. McLintock used a cane to tap the body, face, and head, finding no soft tissue anywhere. He noted that the sound was similar to tapping a brick wall, and believed the remains to weigh more than 400 lb (180 kg). William Austin, the cemetery caretaker, estimated 500 lb (230 kg), which made it difficult for the men to carry the remains to the new site. The original wooden grave marker was moved to the new site, but by 1891 it had been destroyed by souvenir hunters whittling pieces from it, and it was replaced with a statue. This, in turn, was destroyed by souvenir hunters and replaced in 1902 by a life-sized sandstone sculpture of Hickok. This, too, was badly defaced, and was then enclosed in a cage for protection. The enclosure was cut open by souvenir hunters in the 1950s, and the statue was removed.[59]

Hickok is currently interred in a ten-foot (3 m) square plot at the Mount Moriah Cemetery, surrounded by a cast-iron fence, with a U.S. flag flying nearby.[60] A monument has been built there. It has been reported that Calamity Jane was buried next to him, according to her dying wish. Four of the men on the self-appointed committee who planned Calamity's funeral (Albert Malter, Frank Ankeney, Jim Carson, and Anson Higby) later stated that, since Hickok had "absolutely no use" for Jane in this life, they decided to play a posthumous joke on him by laying her to rest by his side.[61] Potato Creek Johnny, a local Deadwood celebrity from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, is also buried next to Wild Bill.[62]

Pistols known to have been carried by Hickok

Hickok's favorite guns were a pair of Colt 1851 Navy Model (.36 caliber) cap-and-ball revolvers. They had ivory grips and silver plating and were ornately engraved with "J.B. Hickok–1869" on the backstrap.[63] He wore his revolvers butt-forward in a belt or sash (when wearing city clothes or buckskins, respectively), and seldom used holsters per se; he drew the pistols using a "reverse", "twist" or cavalry draw, as would a cavalryman.[6]

At the time of his death Hickok was wearing a Smith & Wesson Model 2 Army Revolver. Bonhams auction company offered this pistol at auction on November 18, 2013, in San Francisco, California,[64] described as Hickok's Smith & Wesson No. 2, serial number 29963, a .32 rimfire with a six-inch barrel, blued finish and varnished rosewood grips. The gun did not sell, because the high bid ($220,000) did not meet the reserve price set by the gun's owners.[65]

In popular culture

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wild Bill Hickok. |

The 1923 Western silent film movie Wild Bill Hickok was directed by Clifford Smith and starred William S. Hart as Hickok. The film was released on November 18, 1923, by Paramount Pictures.[66][67] A print of the film is maintained in the Museum of Modern Art film archive.[68]

Hickok's birthplace is now the Wild Bill Hickok Memorial and is a listed historic site under the supervision of the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. The town of Deadwood, South Dakota reenacts Hickok's murder and McCall's capture every summer evening.[57] Hickok has remained one of the most popular and iconic figures of the American Old West and is still frequently depicted in popular culture, including literature, film, and television.

It is difficult to separate the truth from fiction about Hickok. He was the hero of the first dime novel of the Western era and in many ways one of the first comic book heroes. He kept company with others who achieved fame in this way. In dime novels, Hickok's exploits made him seem larger than life. In truth, most of the stories were greatly exaggerated or fabricated by both the writers and Hickok.

In 1979, Hickok was inducted into the Poker Hall of Fame.[69]

Notes

- ↑ Judge Boyd told the jury, "The defendant cannot set up justification that he acted in self-defense if he was willing to engage in a fight with the deceased. To be entitled to acquittal on the ground of self-defense, he must have been anxious to avoid a conflict, and must have used all reasonable means to avoid it. If the deceased and defendant engaged in a fight or conflict willingly on the part of each, and the defendant killed the deceased, he is guilty of the offense charged, although the deceased may have fired the first shot."

- ↑ Judge Boyd said, "That when danger is threatened and impending a man is not compelled to stand with his arms folded until it is too late to offer successful resistance and if the jury believe from the evidence that Tutt was a fighting character and a dangerous man and that [Defendant] was aware such was his character and that Tutt at the time he was shot by the Deft. was advancing on him with a drawn pistol and that Tutt had previously made threats of personal injury to Deft. ... and that Deft. shot Tutt to prevent the threatened impending injury [then] the jury will acquit."

- ↑ Hickok is believed to have killed five men (one by accident), was an accessory in the deaths of three others, and wounded another.

- ↑ For details, see Evening Star, July 1, 1867, which contains a garbled report of eleven men killed by Indians at Fort Harker. It also reports the death of one and the wounding of a second railroad man by Indians near Fort Harker (the two casualties are confirmed). The report of the larger number of deaths may confused this incident with another fight with Indians, at Fort Wallace, Kansas, in which a number of soldiers were killed and wounded. For the Fort Wallace fight and casualties, see The Sun, July 15, 1867.

- ↑ The "special election" may not have been legal, as a letter dated September 17 to the governor of Kansas noted that Hickok had presented a warrant for an arrest which was rejected by the Fort Hays commander, because, when asked to produce his commission, Hickok admitted that he had never received one.

- ↑ John Kyle was awarded the Medal of Honor on 8 July 1869, at Republican River, Kansas, during the Indian campaigns. Kyle John.

- ↑ McCall alleged that John Varnes, a Deadwood gambler, had paid him to murder Wild Bill. When Varnes could not be found, McCall then implicated Tim Brady in the plot. Brady, like Varnes, had disappeared from Deadwood and could not be found.

- ↑ Dead man's hand was an established poker idiom for various different hands long before Hickok died. In 1886, ten years after Hickok's death, the dead man's hand was described as "three Jacks and a pair of Tens" in a North Dakota newspaper, which attributed the term to a specific game held in Illinois 40 years earlier, indicating Hickok's hand had yet to gain widespread popularity. Eventually, Hickok's aces and eights became widely known as the dead man's hand. The History of the Dead Man's Hand Explained.

- ↑ The old cemetery was in an area that was better suited for the constant influx of new settlers to live on, so the remaining bodies there were eventually also moved up the hill to the Mount Moriah Cemetery (in the 1880s).

References

- ↑ They Called Him Wild Bill: The Life and Adventures of James Butler Hickok. pp. 4–5.

- 1 2 Odrowaz-Sypniewska, Margaret. James Butler Hickok/"Wild Bill".

- 1 2 "James Butler 'Wild Bill' Hickok, Early Deadwood". Black Hills Visitor Magazine. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ↑ Rosa, Joseph G. (1979). They Called Him Wild Bill. University Press of Oklahoma. p. 306. Reddish shades of hair appear black in early photographic processes because of their sensitivity, primarily to blue light.

- ↑ Jayhawkers were also often referred to as "Red Legs" because of the distinctive feature of their uniform leggings.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Martin, George (1975). James Garry, ed. Guns of the Gunfighters. Peterson Publishing. ISBN 0-8227-0095-6. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ↑ They Called Him Wild Bill: The Life and Adventures of James Butler Hickok. p. 51: the name was inspired by his "sweeping nose and protruding upper lip".

- ↑ "Wild Bill" Hickok Court Documents. Nebraska State Historical Society. 1861 subpoena issued to Monroe McCanles to testify against Duck Bill.

- ↑ Fido, Martin (1993). The Chronicle of Crime. p. 24 (citing an 1861 newspaper article reporting the McCanles shooting). ISBN 1-84442-623-8.

- ↑ Kelsey, D. M. (1888). Our Pioneer Heroes and Daring Deeds: The Lives and Famous Exploits of Boone ... and Other Hero Explorers, Renowned Frontier Fighters, and Early Settlers of America, from the Earliest Times to the Present. Scammell. pp. 535–.

- ↑ Miller, Nyle H. (200). Why the West Was Wild. University Press of Oklahoma. pp 184–191. ISBN 0-8061-3530-1.

- ↑ Rosa, Joseph G. (2003). Wild Bill Hickok, Gunfighter: An Account of Hickok's Gunfights. University Press of Oklahoma. ISBN 0-8061-3535-2.

- ↑ ""The Lenexa Police Department History"". Archived from the original on June 24, 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-24..

- ↑ Kelsey, D. M. (2004). Our Pioneer Heroes and Their Daring Deeds. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 355–391. ISBN 1-4179-6305-0. Originally published in 1883.

- 1 2 Rosa, Joseph G. (1987). They Called Him Wild Bill: The Life and Adventures of James Butler Hickok (second ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 45–51. ISBN 978-0806115382.

- ↑ "Rock Creek Station State Historical Park". Main Street Consulting Group. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- 1 2 Rosa, Joseph G. James 'Wild Bill' Hickok.

- ↑ The Killing of David Tutt, 1865. Springfield, Greene County, Missouri. History of Greene County, Missouri. Western Historical Company, 1983. USGenWeb Archives.net.

- ↑ "Spartacus Educational". Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- ↑ Rosa, Joseph G. (1996). pp. 116–123.

- ↑ Lubet, Steven (2001). "Legal Culture, Wild Bill Hickok and the Gunslinger Myth". UCLA Law Review, vol. 48, no. 6. Archived February 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Buel, James William (1880). Life and Marvelous Adventures of Wild Bill, the Scout.

- ↑ Miller, Nyle H. (2003). Why the West was Wild. University Press of Oklahoma. p. 185. ISBN 0-8061-3530-1.

- ↑ For confirmation that Hickok was employed as a U.S. Army scout fighting Indians in Kansas in the summer of 1867, see Ames, George Augustus, Ups and Downs of a Army Officer, p. 232.

- 1 2 Miller, Nyle H. (2003). Why the West Was Wild. University Press of Oklahoma. pp. 186–189. ISBN 0-8061-3530-1.

- ↑ "Ellsworth, Kansas History". Droversmercantile.com. Retrieved August 2, 2012.

- 1 2 Miller, Nyle H.; Rosa, Joseph W. (1963). Why the West Was Wild: A Contemporary Look at the Antics of Some Highly Publicized Kansas Cowtown Personalities. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3530-1.

- ↑ Otero, Miguel Antonio (1936). My Life on the Frontier, 1864–1882. Sunstone Press. p. 16.

- ↑ "Wild Bill Hickok: Biography". Spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk. Retrieved August 2, 2012.

- ↑ Officer Down Memorial Page: Thomas J. Smith.

- ↑ "Hardin Credited with 27 Killings". The Wichita City Eagle, August 30, 1877, p. 2, col. 6 (report of his arrest).

- 1 2 "Captor of John Wesley Hardin: John B. Armstrong / Killer of John Wesley Hardin: John Henry Selman". ancestry.com.

- ↑ Rosa, Joseph G. (1996). Wild Bill Hickok: The Man and His Myth. University Press of Kansas. p. 110.

- ↑ Border Roll Incident.

- ↑ John Wesley Hardin Collection. Texas State University.

- ↑ Hardin, John Wesley (1896). The Life of John Wesley Hardin: As Written by Himself. Seguin, Texas: Smith & Moore. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-8061-1051-6. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ↑ Shooting stray dogs within city limits was legal, and a 50-cent bounty was paid by the city for each one shot.

- ↑ "Special Deputy Marshal Mike Williams". The Officer Down Memorial Page (ODMP).

- ↑ Who Was Wild Bill Hickok?.

- ↑ Little, Theophilus. "Early Days in Abilene". Loose-leaf notebook, p. 21.

- ↑ The Life of Hon. William F. Cody, Known as Buffalo Bill, the Famous Hunter, Scout and Guide: An Autobiography. Hartford, Connecticut: F. E. Bliss, 1879. p. 329.

- ↑ Buffalo Bill Museum & Grave, Golden, Colorado.

- ↑ "The State Journal (Jefferson City, Mo.), 1872–1886. August 18, 1876, image 3". loc.gov.

- ↑ Griske, Michael (2005). The Diaries of John Hunton. Heritage Books. pp. 89, 90. ISBN 0-7884-3804-2.

- ↑ "Charlie Utter, Early Deadwood". Black Hills Visitor Magazine.

- ↑ "Famous Last Words". google.com.

- ↑ "Jack McCall - The Coward That Killed Wild Bill Hickok". Legends of America. November 2014. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Wild Bill's Death Chair". Deadwood photos. Archived from the original on March 13, 2012. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- ↑ Campagna, Jeff. "American Wonder Wild Bill Hickok Shot and Killed from Behind on This Day in History". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved June 6, 2012.

- ↑ Bozeman Avant Courier, December 22, 1876, image 1, testimony of George M. Shingle.

- ↑ Eriksmoen, Curt (September 2, 2012). "Riverboat captain 'carried' bullet that killed Hickok". The Bismarck Tribune. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ McClintock, John S. Pioneer Days in the Black Hills.

- ↑ McLaird, James D. (2008). Wild Bill Hickok and Calamity Jane: Deadwood Legends. South Dakota State Historical Society. ISBN 0977795594.

- 1 2 McManus, James (2009). Cowboys Full: The Story of Poker. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 134. ISBN 0374299242.

- ↑ Griske (2005). p. 87.

- 1 2 Richardson, Leander P. (April 1877). "A Trip to the Black Hills". Scribner's.

- 1 2 ""Jack McCall and the Murder of Wild Bill Hickok"". Archived from the original on March 13, 2012. Retrieved 2008-08-04.. Black Hills Visitor.

- ↑ Rosa, Joseph G. "Wild Bill Hickok: Pistoleer, Peace Officer and Folk Hero". History net. Accessed September 2015. Originally published in Wild West.

- ↑ Rosa, Joseph G. (1979). They Called Him Wild Bill. University Press of Oklahoma. p. 305.

- ↑ Straub, Patrick (10 November 2009). It Happened in South Dakota: Remarkable Events That Shaped History. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-7627-6171-5.

- ↑ Griske (2005). p. 89.

- ↑ Weiser, Kathy (2011). "South Dakota Legends – John Perrett, aka: Potato Creek Johnny". Legends of America. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- ↑ Photograph of Wild Bill Hickok's Colt Model 1851 Navys. Connecticut State Library, State Archives.

- ↑ "Wild Bill Hickok's Smith & Wesson No. 2 Revolver on Offer at Bonhams This Fall". Retrieved March 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Wild Bill Hickok's Death-Day Revolver Fails to Sell at California Auction". New York Daily News. Retrieved March 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Wild-Bill-Hickok - Trailer - Cast - Showtimes - NYTimes.com". nytimes.com. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ↑ "Wild Bill Hickok". afi.com. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ↑ "Wild Bill Hickok". silentera.com. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ↑ "Poker Hall of Fame". WSOP.com. Caesars Interactive Entertainment, Inc. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

Bibliography

- Bird, Roy (1979). "The Custer-Hickok Shootout in Hays City." Real West, May 1979.

- Buel, James Wilson (1881). Heroes of the Plains, or Lives and Adventures of Wild Bill, Buffalo Bill and Other Celebrated Indian Fighters. St. Louis: Historical Publishing.

- DeMattos, Jack (1980). "Gunfighters of the Real West: Wild Bill Hickok." Real West, June 1980.

- Hermon, Gregory (1987). "Wild Bill's Sweetheart: The Life of Mary Jane Owens." Real West, February 1987.

- Matheson, Richard (1996). The Memoirs of Wild Bill Hickok. Jove. ISBN 0-515-11780-3.

- Nichols, George Ward (1867). "Wild Bill." Harper's New Monthly Magazine, February 1867.

- O'Connor, Richard (1959). Wild Bill Hickok. Garden City, New York: Doubleday.

- Rosa, Joseph G. (1964, 1974). They Called Him Wild Bill: The Life and Adventures of James Butler Hickok. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1538-6.

- Rosa, Joseph G. (1977). "George Ward Nichols and the Legend of Wild Bill Hickok." Arizona and the West, Summer 1977.

- Rosa, Joseph G. (1979). "J.B. Hickok, Deputy U.S. Marshal." Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains, Winter 1979.

- Rosa, Joseph G. (1982, 1994). The West of Wild Bill Hickok. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2680-9.

- Rosa, Joseph G. (1982). "Wild Bill and the Timber Thieves." Real West, April 1982.

- Rosa, Joseph G. (1984). "The Girl and the Gunfighter: A Newly Discovered Photograph of Wild Bill Hickok." Real West, December 1984.

- Rosa, Joseph G. (1996). Wild Bill Hickok: The Man and His Myth. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0773-0.

- Rosa, Joseph G. (2003). Wild Bill Hickok Gunfighter: An Account of Hickok's Gunfights. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3535-2.

- Turner, Thadd M. Wild Bill Hickok: Deadwood City – End of Trail. Universal Publishers, 2001. ISBN 1-58112-689-1

- Wilstach, Frank Jenners (1926). Wild Bill Hickok: The Prince of Pistoleers. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Page.

External links

- Wild Bill Hickok collection at Nebraska State Historical Society

- James Butler "Wild Bill" Hickok at Find a Grave