Bilibil people

Prior to 1904, the Bilibil people lived on an island offshore from Madang, trading clay pots along the coast from Karkar Island to western Morobe Province. The island was too small to produce enough food for the inhabitants, and the trade therefore was an essential element of their life. They moved to the mainland to their existing village site to improve their subsistence levels.

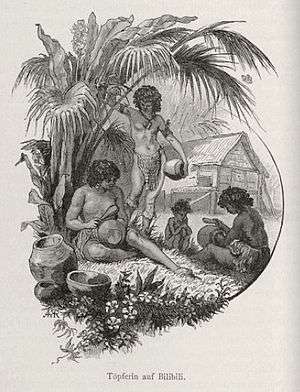

Pot making

Bilibil women make pots, which are still produced in the traditional way. Clay is collected in the bush, mixed with sand and water and left to dry. A few days later it is formed into a wet mixture and again left to dry.

Then the women pull off enough clay and shape the lip of their pot. They hollow out the inside with a stone and beat the outside with a flat board. It must then be left to dry again before the final smoothing takes place. Before they are fired, red clay is painted on the pots. This turns them a glossy red and black when they are pulled out of the fire.

These pots are put to many uses: most importantly, they are used for bride price ceremonies. Sometimes they are still bartered for food as in the old days. The inland people come down from their mountains and meet the Bilibils at a pre-arranged place. The pots are then exchanged for taro and yams from the mountains. No money is used in these exchanges.

Relationship to the ocean

Over the centuries the Bilibils have been great seamen, and they sailed their large two-masted canoes for hundreds of kilometres along the coast. They would call into many villages and trade their pots for food, wooden bowls, pigs and other trading goods.

The weather man or likon would decide what day was the best to begin the trading trip. He was believed to have special powers over the wind and the sea. If he was on a canoe when the sea became rough, he would make magic over some ginger which he cooked in an old pot and then he would spit the ginger on the waves, calling on the masalai or spirits of the sea to help them.

In 1978 they built a one-masted canoe which they sailed into Madang. It had been forty years since they had built one of these canoes and there were only four old men left who knew how to build them.

The older men taught the other men how to build the canoe. They went to the bush to gather materials. Tall trees were cut down and split in two for the plank sides of the hull which had been hollowed in another village. Smaller trees were cut for the outrigger and the supports.

Everything was lashed together with vines from the bush. A wooden cockatoo, a clan totem, was attached to the mast which was then hoisted into position. Then a shelter was built from bamboo and palm leaves on top of the platform. Finally a large sail was measured out on the ground and woven out of pandanus leaves. When attached to the mast it could be furled or unfurled like a large blind.

Previously, the men used tools made from wood, pig's bone, sharpened bamboo and stone.

In the old days the roofs of the houses came to the ground. Each clan had a men's house which the women were not allowed to enter. The men had secret meetings inside and played the magic flutes. The women thought the sound of the flutes was the voice of the spirits.

Nowadays each family lives in their own house made from bush materials. They are divided into rooms and have large airy verandahs. The houses are about two metres off the ground and the women sit underneath and make their pots.

Most of the cooking and eating is done outside and the family gathers around the cooking pot waiting for the food to cook. Yams and taro are the staple diet of the Bilibils and these are grown in large gardens behind the village. The men do the hard work of preparing the new gardens, but the women do most of the gardening.

The yams are ready for harvest in June of each year and the harvest time is celebrated with yam feasts. The yams are stored in the yam houses where some are put aside to sprout for the new crop.

Previously, the people marked the beginning of the year by the appearance of a particular cluster of stars referred to as the Pleiades; this cluster appears near June each year. The likon would stay awake at night waiting for the stars to appear and would blow on his conch shell to wake the village. It was a great time for rejoicing as they knew it was now time to harvest the yams.

The men of the village like to keep up the old traditions as much as possible. Every second year the young men go over to Bilibil Island where they are initiated into manhood. The old men instruct the youth in the way to behave now that they are adults.

They stay on the island for about twelve days and then they return across the water to Bilibil Village where they decorate themselves for a parade through the houses. They wear red laplaps now as there are not many mals or bark cloth coverings to wear. Some of the men wear dogteeth headbands and feathers. Later they have feasting and dancing until the early hours of the morning.

References

- ↑ Finsch, Otto (1888). Samoafahrten. Reisen im Kaiser Wilhelms-Land und Englisch-Neu-Guinea in den Jahren 1884 u. 1885 an Bord des Deutschen Dampfers "Samoa". Ferdinand Hirt & Sohn, Leipzig. p. 82. Retrieved 2013-05-26.