Rika's Landing Roadhouse

|

Rika's Landing Roadhouse | |

|

| |

| |

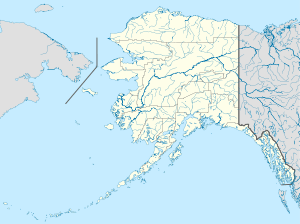

| Location | Mile 252, Richardson Hwy., Big Delta, Alaska |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 64°9′18.84″N 145°50′25.69″W / 64.1552333°N 145.8404694°WCoordinates: 64°9′18.84″N 145°50′25.69″W / 64.1552333°N 145.8404694°W |

| Area | 2.3 acres (0.93 ha) |

| Built | 1909 |

| Architectural style | Multistory Log and clapboard, tarpaper roof with dormers |

| Part of | Big Delta Historic District (#91000252) |

| NRHP Reference # | 76000364[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | September 1, 1976 |

| Designated CP | March 20, 1991 |

Rika's Landing Roadhouse, also known as Rika's Landing Site or the McCarty Roadhouse, is a roadhouse located at a historically important crossing of the Tanana River, in the Southeast Fairbanks Area, Alaska, United States. It is off mile 274.5 of the Richardson Highway in Big Delta.

The roadhouse is named after Rika Wallen, who acquired it from John Hajdukovich and operated it for many years. It became a hub of activity in that region of the interior. With the construction of the ALCAN (now Alaska) Highway and the replacement of the ferry with a bridge downstream, traffic moved away and patronage declined. The roadhouse was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976, and is now a centerpiece of Big Delta State Historical Park, also listed on the National Register.[1]

Background

The Richardson Highway, an important route through the Alaska Interior that contributed significantly to development and settlement of the region, began as a pack trail from the port at Valdez to Eagle, downstream on the Yukon River from Dawson. It was built in 1898 by the U.S. Army to provide an "all-American" route to the Klondike gold fields during the gold rush.[2] After the rush ended, the Army kept the trail open in order to connect its posts at Fort Liscum in Valdez, and Fort Egbert in Eagle. The Valdez-to-Eagle trail, and its branch to Fairbanks, became one of the most important access routes to the Alaska Interior during the Fairbanks' gold rush of 1902, and the 1903 construction of a WAMCATS telegraph line along the trail.[2] This was accomplished by men of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, directed in part by then-Lieutenant Billy Mitchell, who later rose to the rank of general.[3]

Many roadhouses, some 37 in all[4] and some now listed on the National Register of Historic Places, were built along this trail for the convenience of travelers. These roadhouses offered meals, sleeping quarters, and supplies. They were typically located about 15 to 20 miles apart.[5]

Early activity

The Tanana River was one of the major rivers to be crossed by travelers along the Valdez-Eagle trail. A ferry was established just upriver of the Tanana's confluence with the Delta River, at a location then called Bates Landing. Bates Landing was about 12 km (7.5 mi) north of the current settlement of Delta Junction, in the area known now as Big Delta. The government collected a ferry toll on the south side from all those traveling northbound.[6] The WAMCATS telegraph line was relocated to parallel the trail after a fire. McCarty Station was established at the line's crossing of the Tanana in 1907 to maintain the telegraph. Several log cabins housed the telegraph office, a dispatcher, two repairmen and their supplies.[7]

A trading post was constructed on the south bank of the Tanana, at Bates Landing in April 1904 by a prospector named Ben Bennett on his claim of 80 acres (32 ha), but Bennett sold the post and land to Daniel G. McCarty in April 1905. However since E.T. Barnette, the founder of Fairbanks, and McCarty's former employer, had financed the goods in the post, Barnette retained ownership of them. The post property, now being used as a roadhouse, soon became known as McCarty's. Another prospector named Alonzo Maxey, and a friend, built Bradley's Roadhouse to compete with McCarty's and by 1907, McCarty's had been transferred to Maxey.[8]

Hajdukovich era

In 1906,[6] or perhaps sometime after,[5][9] Jovo 'John' Hajdukovich (Montenegrin: Jovo Hajduković, Јово Хајдуковић), an entrepreneur who had come to Alaska from Montenegro in 1903,[10] sensed a business opportunity and purchased the trading post and roadhouse from Maxey. Hajdukovich built a new and bigger roadhouse in 1909 using logs floated downriver.[7] He continued to use the old trading post to store his gear.

Hadukovich had other business interests, including prospecting, freighting, acting as a hunting guide by taking hunting parties into the nearby Granite Mountains, and trading with, and advocating for, the Athabaskan natives.[11] (Later he was instrumental in founding the Tetlin Reserve.[12]) After he was appointed as US Game Commissioner for the area,[13] he could no longer personally operate the roadhouse full-time. As with many informally managed roadhouses, Hadukovich asked travelers to "make themselves at home and leave some money on the table" for what they used.[13] Despite this informality, the operations prospered.

Starting in 1904, the trail was improved and upgraded.[7][14] In 1907,[15] By 1910, the Alaska Road Commission completed the upgrade, making the trail usable as a wagon road. Major Wilds P. Richardson led the project and later became the namesake for the highway. He was promoted to general later in his career.[7]) Stages plied the road, using horse-drawn sledges in winter and wagons in summer.[15] By 1913 the roadhouse was a local center of activity for gold prospectors, local hunters, traders, and freighters.[7][16]

Meanwhile Erika 'Rika' Wallen, born Lovisa Erika Jakobson in 1874 on a farm near Örebro Sweden, immigrated with her sister in 1891 to the United States. They traveled to Minneapolis, Minnesota to join their brother Carl Jakobson. There they changed their last name to Wallen to distinguish themselves from the many other Jacobsons and Jakobsons. After Carl died in an accident, the sisters moved to San Francisco, which they heard was booming. Rika took a job as a cook for the Hills Brothers coffee family, which lasted until the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

In 1916 Rika Wallen traveled to Valdez, reportedly "because she thought Alaska would be like Sweden".[17]

Rika Wallen takes over the Roadhouse

After jobs cooking at the Kennecott copper mine and for a Fairbanks boarding house, Rika Wallen made her way to Big Delta. In 1917,[7] or 1918,[13] she was hired by Hadukovich to manage operations at his roadhouse, then still known as McCarty's.

Although Hadukovich had many business interests, he was not always solvent. For example, in later years he failed to be paid for timber he supplied to the ALCAN Highway project due to not keeping adequate records.[10] In either 1918,[10] or 1923,[7] he transferred ownership of the roadhouse to Wallen for "$10.00 and other considerations," presumably in lieu of back wages.[7] Their friendship and partnership continued for many years; historians and writers have not been able to define their relationship.[10] Following local custom of naming places for people, the roadhouse was soon named Rika's.[16] At that time, the roadhouse had eleven bedrooms, a living room, and a large kitchen/dining area.[18]

By 1925, Wallen had applied for US citizenship, and filed a homestead claim on 160 acres (65 ha).[4] She began growing food and raising livestock, including sheep, chicken, and goats. Sheep provided wool that she wove, and the goats provided milk, from which she made butter and cheese.[4] She also raised silver fox, ducks, geese, rabbits and honeybees. She cultivated grain by using a yoke of oxen for plowing.[19] Rika was a talented farmer, and she successfully grew crops where others failed. She developed a heating and ventilation system for her stable to protect the livestock through the harsh winters.[17]

When Wallen bought the roadhouse, it still had packed dirt floors and rough wood walls. To improve the interior, she scavenged wallpaper, sometimes using different patterns on different walls of the same room.[18] She made a hardwood parquet floor from wooden kerosene crates collected from the freighters and boatmen who patronized the roadhouse.[13] Her ability to grow crops and to make a pleasant space transformed the inn and its offerings. For meals, she provided fresh milk and eggs, berries, fish, game, and produce picked from the garden and nearby orchard. Afterward, travelers could go to clean, comfortable beds in the multi-story building.[4] A 1929 travelogue of the Richardson Highway described Rika's by the following: "a commodious roadhouse boasting of such luxuries as fresh milk and domestic fowls."[20]

About 1926, Rika added a wing, which she used for additional living space, a liquor store, fur storage, and the Big Delta (then known as Washburn)[4] Post Office.[18] She was appointed as the US postmaster and served until 1946.[18] Eventually Wallen also homesteaded an adjoining piece of land, bringing her holdings to 320 acres (130 ha).

End of an era

The construction of the Alaska Railroad was completed in 1922, but by the 1930s, due to effects of the Great Depression, freight traffic declined on the railroad. In 1935, the Alaska Road Commission tried to force shippers to use the railroad, and raised the toll at the Tanana ferry crossing to almost 10 dollars a ton. The truckers rebelled at this, with some violent skirmishes. Pirate ferry operations were started, lasting until the start of World War II.[21]

With the coming of the war and construction of the ALCAN Highway, which connected to the Richardson south of Big Delta, road traffic waned further. The ferry crossing was replaced by a wooden bridge, and later, a larger steel bridge was constructed downriver. This caused rerouting of the highway away from the roadhouse, drawing off traffic and travelers. Wallen operated the roadhouse through the 1940s and early 1950s, although in later years guests were by invitation only.[18] John Hajdukovich died in 1965,[10] and Rika Wallen died four years later in 1969.[9]

Big Delta State Historical Park

According to Judy Ferguson in Parallel Destinies, a biography of Hajdukovich and Wallen:

- "For fifty years, Rika was a stake in the ground for the roaming John. While John traded and prospected, Rika ran the hub of the Upper Tanana's cross-roads. Her establishment was "town" to the three hundred people who walked the trails to the Alaskan-Canadian border. John and Rika were the history of the Upper Tanana Valley."[22]

Rika's Roadhouse, the adjacent outbuildings, and property are preserved as the Big Delta State Historical Park.[7] In 1976 the roadhouse was placed on the National Register of Historic Places, and the entire cluster was listed as the "Big Delta Historic District" in 1991.[1][23] The structure was restored in 1984 by Stanton and Stanton Construction (owned and operated by brothers, Eldon and Richard Stanton). It was placed on a new foundation using original timbers, and in some areas, the packing crate floor was restored.[14] It is now operated as a "house museum"; some rooms have been fitted with 1920s-1930s period furniture and accessories donated by local residents.[7] The property also has a food service facility called the "Packhouse Pavilion" operated by a local concessionaire.[24][25]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 Valencia, Kris (2009). The Milepost 2009: Alaska Travel Planner. Morris Communications Corp. pp. 465, 482. ISBN 978-1-892154-26-2.

- ↑ Cooke, James (2002). Billy Mitchell. Lynne Rienner Publishers. pp. 33–37. ISBN 978-1-58826-082-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Interior Alaska 1896–1910 CHANGING LIFESTYLES, DIFFERENT VALUES". Alaska's History & Cultural Studies. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- 1 2 Lundberg, Murray. "Northern Roadhouses, an Introduction". ExploreNorth. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- 1 2 "History". Delta Junction - Alaska's Friendly Frontier. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Big Delta State Historical Park". Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- ↑ Lundberg, Murray. "The History of Big Delta". ExploreNorth. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- 1 2 "Delta Junction". Travel Alaska. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cook, Debbie. "Review of Parallel Destinies". Delta News Web. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ Ferguson, Judy. "Parallel Destinies, An Alaskan Odyssey". Judy Ferguson's Outpost. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ as mentioned in the review at "Alaskrafts ~ BOOK STORE ~ PARALLEL DESTINIES". furshack.com. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- 1 2 3 4 "Rika's Virtual Tour - roadhouse". Rika's Landing Concessionaire. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- 1 2 "Historic Roadhouse". Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- 1 2 "Richardson Highway". Delta Junction - Alaska's Friendly Frontier. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- 1 2 "Visitor Guide: Museums". City of Delta Junction, Alaska. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- 1 2 Winquist, Alan; Rousselow-Winquist, Jessica (2006). Touring Swedish America: where to go and what to see. Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-87351-559-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Big Delta". Vacation Country Travel Guide. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ "Alaska Highway". John Hall's Alaska. Archived from the original on November 2, 2008. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ "Rika's Virtual Tour - farm animals". Rika's Landing Concessionaire. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ "Rika's Virtual Tour - ferry". Rika's Landing Concessionaire. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ↑ "Alaskrafts ~ BOOK STORE ~ PARALLEL DESTINIES". furshack.com. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ "NRHP nomination for Big Delta Historic District" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

- ↑ "Rika's Virtual Tour - Packhouse Pavilion". Rika's Landing Concessionaire. Retrieved 2009-08-29.

- ↑ "Fodor's review". Fodor's. Retrieved 2009-08-30.

Further reading

- Ferguson, Judy (2002). Parallel Destinies. Glas Publishing, ISBN 978-0-9716044-0-7. (A biography of Rika Wallen and John Hajdukovich, written by a resident of Big Delta).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rika's Landing Roadhouse. |

- Official website of Big Delta State Historical Park

- Big Delta State Historical Park at the Alaska Department of Natural Resources Northern Area State Parks office

- NRHP document

- A pictorial tour of the Big Delta State Historical Park

- Big Delta at the Alaska Department of Commerce Community Information Database

- Itinerary of a mid-1920s visit to Alaska including a stay at Rika's

- Going Places Alaska And The Yukon For Families by Nancy Thalia Reynolds at Google Books

- Alaska Off the Beaten Path (6th edition) by Melissa Devaughn and Deb Vanasse at Google Books

- Media from Alaska's Digital Archives:

- Four pioneers photo of John, Rika, and two other pioneers late in life

- Still image of current ferry at McCarty (use of that name dates it as older than the next two images)

- Another still image of ferry crossing the Tanana, 1930, Rika's visible in background. (from Digital Alaska)

- Video clip of ferry crossing the Tanana, 1935–36, Rika's visible in background. (from Digital Alaska)