Bhojeshwar Temple

| Bhojeshwar Temple | |

|---|---|

| |

Bhojeshwar Temple Location in India | |

| Name | |

| Other names | Bhojeśvara Mandir, Bhojeshvara Temple, Bhojpur Temple |

| Geography | |

| Coordinates | 23°06′01″N 77°34′47″E / 23.1003°N 77.5797°ECoordinates: 23°06′01″N 77°34′47″E / 23.1003°N 77.5797°E |

| Country | India |

| State/province | Madhya Pradesh |

| District | Raisen |

| Locale | Bhojpur |

| Elevation | 463 m (1,519 ft) |

| Culture | |

| Primary deity | Shiva |

| Important festivals | Maha Shivaratri |

| History and governance | |

| Date established | 11th century |

| Governing body | Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) |

The Bhojeshwar Temple is an incomplete Hindu temple in Bhojpur village of Madhya Pradesh, India. Dedicated to Shiva, it houses a 7.5 feet (2.3 m) high lingam in its sanctum.

The temple's construction is believed to have started in the 11th century, during the reign of the Paramara king Bhoja. The construction was abandoned for unknown reasons, with the architectural plans engraved on the surrounding rocks. The unfinished materials abandoned at the site, the architectural drawings carved on the rocks, and the mason's marks have helped scholars understand the temple construction techniques of 11th-century India. The temple has been designated as a Monument of National Importance by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).

History

The Bhojpur temple is believed to have been constructed by the 11th-century Paramara king Bhoja. Tradition also attributes to him the establishment of Bhojpur and the construction of now-breached dams in the area.[1] Because the temple was never completed, it lacks a dedicatory inscription. However, the name of the area ("Bhojpur") corroborates its association with Bhoja.[2]

This belief is further supported by the site's sculptures, which can be dated to the 11th century with certainty.[1] A Jain temple in Bhojpur, which shares the same sets of mason's marks with the Shiva temple, has an inscription explicitly dated to 1035 CE. Besides several literary works, historical evidence confirms that Bhoja's reign included the year 1035 CE: the Modasa copper plates (1010-11 CE) were issued by Bhoja; and the Chintamani-Sarnika (1055 CE) was composed by his court poet Dasabala. Moreover, the area around the temple once featured three dams and a reservoir. The construction of such a large Shiva temple, dams and reservoir could have only been undertaken by a powerful ruler. All this evidence appears to confirm the traditional belief that the temple was commissioned by Bhoja. Archaeology professor Kirit Mankodi dates the temple to the later part of Bhoja's reign, around mid-11th century.[3]

The Udaipur Prashasti inscription of the later Paramara rulers states that Bhoja "covered the earth with temples" dedicated to the various aspects of Shiva, including Kedareshvara, Rameshwara, Somanatha, Kala, and Rudra. Tradition also attributes the construction of a Saraswati temple to him (see Bhoj Shala). The Jain writer Merutunga, in his Prabandha-Chintamani, states that Bhoja constructed 104 temples in his capital city of Dhara alone. However, the Bhojpur temple is the only surviving shrine that can be attributed to Bhoja with some certainty.[4]

According to a legend in Merutunga's Prabandha-Chintamani, when Bhoja visited Srimala, he told the poet Magha about the "Bhojasvāmin" temple that he was about to build, and then left for Malwa (the region in which Bhojpur is located).[5] However, Magha (c. 7th century) was not a contemporary of Bhoja, and therefore, the legend is anachronistic.[6]

The temple originally stood on the banks of a reservoir 18.5 long and 7.5 miles wide.[7] This reservoir was formed through construction of 3 earth-and-stone dams during Bhoja's reign. The first dam, built on Betwa River, trapped the river waters in a depression surrounded by hills. A second dam was constructed in a gap between the hills, near present-day Mendua village. A third dam, located in present-day Bhopal, diverted more water from the smaller Kaliasot river into the Betwa dam reservoir. This man-made reservoir existed until 15th century, when Hoshang Shah emptied the lake by breaching two of the dams.[1]

Funerary monument theory

The Bhojpur temple features several peculiar elements, including the omission of a mandapa connected to the garbhagriha (sanctum), and the rectilinear roof instead of the typical curvilinear shikhara (dome tower). Three of the temple's walls feature a plain exterior; there are some carvings on the entrance wall, but these are of the 12th century style. Based on these peculiarities, researcher Shri Krishna Deva proposed that the temple was a funerary monument. Deva's hypothesis was further corroborated by the discovery of a medieval architectural text by M. A. Dhaky. This fragmentary text describes the construction of memorial temples erected over the remains of a dead person, conceived of as vehicles for ascent to the heaven. Such temples were called svargarohana-prasada ("temple commemorating the ascent to the svarga or heaven"). The text explicitly states that in such temples, a roof of receding tiers should be used instead of the typical shikhara. Kirit Mankodi notes that the superstructure of the Bhojpur temple would have been in this exact form upon its competition. He speculates that Bhoja may have started the construction of this shrine for the peace of soul of his father Sindhuraja or of his uncle Munja, who suffered a humiliating death in enemy territory.[8]

Abandonment of construction

It appears that the construction work stopped abruptly.[9] The reasons are not known, but historians speculate that the abandonment may have been triggered by a sudden natural disaster, a lack of resources, or a war. Before its restoration during 2006–07, the building lacked a roof. Based on this, archaeologist KK Muhammed theorizes that the roof could have collapsed due to a mathematical error made while calculating the load; subsequently, circumstances might have prevented Bhoja from rebuilding it.[10]

The evidence from the abandoned site has helped the scholars understand the mechanics and organisation of 11th century temple construction.[11] To the north and the east of the temple, there are several quarry sites, where unfinished architectural fragments in various stages of carving were found. Also present are the remains of a large sloping ramp erected for carrying the carved slabs from the quarries to the temple site.[4] Several carvings brought to the temple site from the quarries had been left at the site. The ASI moved these carvings to a warehouse in the 20th century.[9]

Detailed architectural plans for the finished temple are engraved on the rocks in the surrounding quarries.[12][4] These architectural plans indicate that the original intention was to build a massive temple complex with many more temples. The successful execution of these plans would have made Bhojpur one of the largest temple complexes in India.[10]

-

An unfinished statue at the site

-

Architectural fragments at one of the quarry sites

-

Carved rock fragments near the entrance

The marks of over 1,300 masons are engraved on the temple building, the quarry rocks and two other shrines in the village. This includes the names of 50 masons engraved on the various portions of the temple structure. Other marks are in the form of various symbols such as circle, crossed circle, wheel, trident, swastika, conch shell, and Nagari script characters. These marks were meant to identify the amount of work completed by individuals, families or guilds involved in the construction. The marks would have been erased while giving the finishing touches, had the temple been completed.[7]

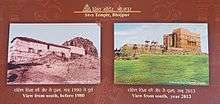

Conservation and restoration

By 1950, the building had become structurally weak because of the regular rainwater percolation and removal of the stone veneers.[13] In 1951, the site was handed over to the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) for conservation, in accordance with the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act 1904.[14] During the early 1990s, the ASI repaired the damaged steps of the platform and the sanctum, and also restored the missing ones. It also restored the facade on the north-west corner of the temple.[15]

During 2006–07, the ASI team supervised by KK Muhammed carried out a restoration of the monument. The team added a missing pillar to the structure. The 12-tonne pillar was carved out of a single stone by expert masons and sculptors in a style that matches the original. The monolith was procured from the area near Agra after a nation-wide search for material matching the stone originally used in the temple. The team was unable to procure a crane with a sufficiently long boom. So, they lifted the monolith 30 feet up with the help of a system of pulleys and levers, which took 6 months to devise.[10][13] KK Muhammed noted that two other pillars in the temple weigh 33 tonnes, and are also carved out of a single stone: it must have been very challenging for the original builders to erect these pillars without modern technology and resources.[10]

The team closed the ceiling with a new architectural component matching the original one, to stop the water percolation. This fibreglass component weighs less than the original one, thus reducing unnecessary weight which could damage the structure. To further prevent the rainwater from getting in, the ASI also closed the portion between the wall and the superstructure by placing slanting stone slabs. In addition, the ASI placed new stone veneers matching the original ones on the northern, southern and western exterior walls of the temple.[13] The ASI also cleaned the dirt that had accumulated on the temple walls over the past few centuries.[10]

Architecture

The temple lies on a platform 115 feet (35 m) long, 82 feet (25 m) wide and 13 feet (4.0 m) high. On the platform lies a sanctum containing a large lingam.[16] The sanctum plan comprises a square; on the outside, each side measures 65 feet (20 m); on the inside, each measures 42.5 feet (13.0 m).[17]

The lingam is built using three superimposed limestone blocks. The lingam is 7.5 feet (2.3 m) high and 17.8 feet (5.4 m) in circumference. It is set on a square platform, whose sides measure 21.5 feet (6.6 m).[18] The total height of the lingam, including the platform is over 40 feet (12 m).[19]

The doorway to the sanctum is 33 feet (10 m) high.[16] The wall at the entrance features sculptures of apsaras, ganas (attendants of Shiva) and river goddesses.[19]

The temple walls are window-less and are made of large sandstone blocks. The pre-restoration walls did not have any cementing material. The northern, southern and eastern walls feature three balconies, which rest on massive brackets. These are faux balconies that are purely ornamental. They are not approachable from either inside or outside of the temple, because they are located high up on the walls, and have no openings on the interior walls. The northern wall features a makara-shaped spout, which provided a drainage outlet for the liquid used to bathe the lingam.[16] Other than the sculptures on the front wall, this makara sculpture is the only carving on the external walls.[9] 8 images of goddesses were originally placed high up on the four interior walls (two on each wall); only one of these images now remains.[19]

-

Ceiling with the ASI's fibreglass component

-

Gana sculpture

-

Lingam in the sanctum

-

Sculptures at the entrance

-

Makara-shaped drainage spout

-

.jpg)

Faux balcony

-

View from the ground level

The four brackets supporting the cornerstones feature four different divine couples: Shiva-Parvati, Brahma-Shakti, Rama-Sita, and Vishnu-Lakshmi. A single couple appears on all the three faces of each bracket.[19]

While the superstructure remains incomplete, it is clear that the shikhara (dome tower) was not intended to be curvilinear. According to Kirit Mankodi, the shikhara was intended to be a low pyramid-shaped samvarana roof, usually featured in the mandapas.[19] According to Adam Hardy, the shikhara probably intended to be of phamsana (rectilinear in outline) style, although it is of bhumija (latina or curvilinear in outline) style in its detailing.[20]

The incomplete but richly carved dome is supported by four octagonal pillars, each 39.96 feet (12.18 m) high.[21][18] Each pillar is aligned with 3 pilasters. These 4 pillars and 12 pilasters are similar to the navaranga-mandapas of some other medieval temples, in which 16 pillars were organized to make up 9 compartments.[19]

The remnants of a sloping ramp can be seen on the north-eastern corner of the building. The ramp is built of sandstone slabs, each measuring 39 x 20 x 16 inches. The slabs are covered with soil and sand.[11] The ramp itself is 300 feet (91 m) long, and slopes upwards to a height of 40 feet (12 m). Originally, the ramp reached up to the temple wall, but currently, a gap exists between the two.[7]

Bhojeshwar Temple Museum

There is a small museum dedicated to Bhojeshwar Shiva Temple and it is situated nearly 200 meters from the main temple. The museum depicts the history of Bhojeshwar Temple trough posters and sketches as well as it covers the reign of Raja Bhoja. The museum describes the reign of Raja Bhoja and important books written by him as well as the mason marks. The museum also hosts a small. There is no entry fee in the museum and the museum is open for visitors from 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM.[22]

Present use

The monument is now under the protection of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).[23] Because of its proximity to the state capital Bhopal (28 km), it attracts a considerable number of tourists. In 2015, the site received the National Tourism Award (2013–14) for the "Best maintained and Disabled Friendly Monument".[24]

Despite being unfinished, the temple is in use for religious purposes. On Maha Shivaratri, thousands of devotees visit the temple.[25][26] The Government of Madhya Pradesh organises the Bhojpur Utsav cultural event at the site every year around Maha Shivaratri.[27] Past performers at the event include Kailash Kher,[28] Richa Sharma, Ganna Smirnova,[27] and Sonu Nigam.[29]

References

- 1 2 3 Mankodi 1987, p. 71.

- ↑ Willis, Michael (2001). "Inscriptions from Udayagiri: locating domains of devotion, patronage and power in the eleventh century". South Asian Studies. 17 (1): 41–53.

- ↑ Mankodi 1987, pp. 71–72.

- 1 2 3 Mankodi 1987, p. 61.

- ↑ Merutunga Ācārya (1901). The Prabandhacintāmani or Wishing-Stone of Narratives. Translated by Charles Henry Tawney. Asiatic Society. p. 49.

- ↑ Hermann Jacobi (1889). "On Bhâravi and Mâgha". Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes. Department of Oriental Studies, University of Vienna. 3: 141.

- 1 2 3 Mankodi 1987, p. 68.

- ↑ Mankodi 1987, p. 72.

- 1 2 3 Mankodi 1987, p. 64.

- 1 2 3 4 5 K. S. Shaini (11 June 2007). "Pray In The Shade". Outlook.

- 1 2 Mankodi 1987, p. 66.

- ↑ Aruna Ghose, ed. (2011). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: India. Penguin. p. 242. ISBN 9780756684440.

- 1 2 3 "Bhojpur: Conservation & Preservation". Archaeological Survey of India, Bhopal Circle. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ↑ "The Gazette of India (page 236)" (PDF). 17 February 1951.

- ↑ B. P. Singh, ed. (1996). Indian Archaeology 1991–92 – A Review (PDF). Archaeological Survey of India. p. 169.

- 1 2 3 Mankodi 1987, p. 62.

- ↑ Mankodi 1987, pp. 62–63.

- 1 2 Bhattacharya & 2007 321.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mankodi 1987, p. 63.

- ↑ Hardy 2007, p. 188.

- ↑ "Bhojpur Savite Temple". Archaeological Survey of India, Bhopal Circle. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ↑ http://knowledgeofindia.com/trip-bhojeshwar-shiva-temple-bhojpur-bhopal/

- ↑ "Alphabetical List of Monuments – Madhya Pradesh". Archaeological Survey of India. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ↑ "Gujarat bags top award for comprehensive development of tourism". DNA. 19 September 2015.

- ↑ "Mahashivratri being celebrated across Madhya Pradesh". Zee News. 7 March 2016.

- ↑ "भगवान भोले के दर्शन को सुबह 4 बजे से लगी लोगों की भीड़, भोजपुर उत्सव शुरू". Dainik Bhaksar (in Hindi). 8 March 2016.

- 1 2 "'Bhojpur Utsav' to observe Mahashivratri". The Pioneer. 26 February 2014.

- ↑ "Kailash Kher performs at Bhojpur Utsav in Bhojpur". The Times of India. 13 March 2013.

- ↑ "Sonu Nigam adds charm to Bhojpur Utsav". The Free Press Journal. 9 March 2016.

Bibliography

- Bhattacharya, Ajoy Kumar (2007). Forestry For The Next Decade. 2. Concept. ISBN 9788180694271.

- Hardy, Adam (2015). Theory and Practice of Temple Architecture in Medieval India: Bhoja's Samarāṅgaṇasūtradhāra and the Bhojpur Line Drawings. Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. ISBN 9789381406410.

- Hardy, Adam (2007). The temple architecture of India. Wiley. ISBN 978-0470028278.

- Mankodi, Kirit (1987). "Scholar-Emperor and a Funerary Temple: Eleventh Century Bhojpur". Marg. National Centre for the Performing Arts. 39 (2): 61–72.

External links

-

Media related to Bhojpur temple at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bhojpur temple at Wikimedia Commons