Bene Israel

| |

| Languages | |

|---|---|

| Traditionally, Marathi; those in Israel, mostly Hebrew | |

| Religion | |

| Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Cochin Jews, Baghdadi Jews, Marathi people |

The Bene Israel ("Sons of Israel"), formerly known in India as the "Native Jew Caste",[1] are a historic community of Jews in India. It has been suggested[2] that it is made up of descendants of one of the disputed Lost Tribes and ancestors who had settled there centuries ago. In the 19th century, after the people were taught about normative (Ashkenazi/Sephardi) Judaism, they tended to migrate from villages in the Konkan area[3] to the nearby cities, primarily Mumbai,[2] but also to Pune, Ahmedabad, and Kolkata, India; and Karachi, in today's Pakistan.[4] Many gained positions with the British colonial authority of the period.

In the early part of the twentieth century, many Bene Israel became active in the new film industry, as actresses and actors, producers and directors. After India gained its independence in 1947, and Israel was established in 1948, most Bene Israel emigrated to Israel.

History

According to Bene Israel tradition, their ancestors had migrated to India after centuries of travel through western Asia from Israel and gradually assimilated to the people around them, while keeping some Jewish customs.[5] Maimonides, the Jewish philosopher, mentioned in a letter that there was a Jewish community living in India: he may have been referring to the Bene Israel.[6]

In the 18th or 19th century, an Indian Jew from Cochin named David Rahabi discovered the Bene Israel in their villages and recognized their vestigial Jewish customs.[7] Some historians have thought their ancestors may have belonged to one of the Lost Tribes of Israel,[8] but the Bene Israel have never been officially recognized by Jewish authorities as such.

Rahabi taught the people about normative Judaism. He trained some young men among them to be the religious preceptors of the community.[9] Known as Kajis, these men held a position that became hereditary, similar to the Cohanim. They became recognized as judges and settlers of disputes within the community.

One Bene Israel tradition places Rahabi's arrival at around 1000CE or 1400, although some historians believe he was not active until the 18th century. They suggest that the "David Rahabi" of Bene Israel folklore is a man named David Ezekiel Rahabi, who lived from 1694 to 1772, and resided in Cochin, then the center of the wealthy Malabar Jewish community.[10][11][12] Others suggest that the reference is to David Baruch Rahabi, who arrived in Bombay from Cochin in 1825.[13]

It is estimated that there were 6,000 Bene Israel in the 1830s; 10,000 at the turn of the 20th century; and in 1948—their peak in India—they numbered 20,000.[14] Since that time, most of the population have emigrated.

Under British colonial rule, many Bene Israel rose to prominence in India. They were less affected than other Indians by the racially discriminatory policies of the British colonists, considered somewhat outside the masses. They gained higher, better paying posts in the British Army when compared with their non-Jewish neighbours.[5] Some of these enlistees with their families later joined the British in the British Protectorate of Aden.[15]

In the early twentieth century, numerous Bene Israel became leaders in the new film industry in India. In addition, men worked as producers and actors: Ezra Mir (alias Edwin Myers) (1903-1993) became the first chief of India's Film Division, and Solomon Moses was head of the Bombay Film Lab Pvt Ltd from the 1940s to 1990s.[16] Ennoch Isaac Satamkar was a film actor and assistant director to Mehboob Khan, a prominent director of Hindi films.[17]

Given their success under the British colonial government, many Bene Israel prepared to leave India at independence in 1947. They believed that nationalism and the emphasis on indigenous religions would mean fewer opportunities for them. Most emigrated to Israel,[18] which was newly established in 1948 as a Jewish homeland.[19][20]

-

Synagogue in Pen, India.

-

Synagogue in Ahmedabad.

-

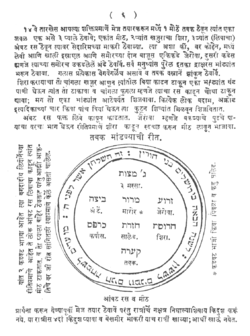

A page from a Haggada shel Pesach in Judaeo-Marathi, printed in Mumbai, 1890.

-

Bene Israel Cemetery, Mumbai.

-

Members of the Jewish community in Madhupura, Ahmedabad.

Alibag

The town of Alibag on the Konkan coast in Maharashtra is named after a Bene Israeli called Ali. Ali was a rich man and owned many coconut and mango orchards in the area. Hence the locals used to call the place "Alichi Bagh" (Marathi for "Gardens of Ali"), or simply "Alibag", and the name stuck.

Genetics

Two independent studies on Indian Jews suggest that there is a substantial genetic admixture with Middle Eastern link.[21][22] The first study dates their arrival to India more than 1100 years ago,[21] whereas another study of 18 genomewide SNP data of Bene Israel has suggested that this population originated from a mixture of Middle Eastern Jews and Indians between 26–30 generations (~850–970 years) ago.[22] The genetics of Bene Israel from India reveals both substantial Jewish and Indian ancestry and with sex bias involving mostly Jewish males and Indian females.[23]

Life in Israel

Between 1948 and 1952, some 2,300 Bene Israel immigrated to Israel.[24] Several rabbis refused to marry Bene Israel to other Jews, on grounds that they were not legitimate Jews under Orthodox law. As a result of sit-down protests and hunger strikes by Orthodox Jews, the Jewish Agency returned 337 individuals of Bene Israel in several groups to India between 1952 and 1954. Most returned to Israel after several years.[25]

In 1962, the Indian press reported that European-Jewish authorities in Israel had treated the Bene Israel with racism.[26][27] They objected to the Chief Rabbi of Israel ruling that, before registering a marriage between Indian Jews and Jews not belonging to that community, the registering rabbi should investigate the lineage of the Indian applicant for possible non-Jewish descent. In case of doubt, they should require the applicant to perform formal conversion or immersion.[26][27]

The alleged discrimination may have been based on the belief by some religious authorities that the Bene Israel were not fully Jewish because of having had intermarriage in the maternal line with Indian natives during their long separation from major communities of Jews. Others thought that was a convenient cover for racially based bias against Jews who were not Ashkenazi or Sephardim.[28] Between 1962 and 1964, the Bene Israel community staged protests against the religious policy. In 1964 the Israeli Rabbinate ruled that the Bene Israel are "full Jews in every respect".[18]

The Report of the High Level Commission on the Indian Diaspora (2012) reviewed life in Israel for the Bene Israel community. It noted that the city of Beersheba in Southern Israel has the largest community of Bene Israel, with a sizable one in Ramla. They have a new kind of transnational family.[29] Generally the Bene Israel have not been politically active and have had modest means. They have not formed continuing economic connections to India and have limited political status in Israel. Jews of Indian origin are generally regarded as Sephardic; they have become well integrated religiously with the Sephardhim community in Israel.[30] Since the late 20th century, members of Bene Israel have also settled in the United States and Canada.

Notable people

- Nissim Ezekiel, poet[31]

- David Abraham Cheulkar (1908–1982), actor in India better known as David, he starred in Boot Polish (1954) and sang "Nanhe Munne Bachche."[16]

- Ezra Mir alias Edwin Myers (1903–1993), producer, the first chief of India's Film Division, called the Information Films of India under British rule; noted in the Guinness Book of World Records as "the producer of the largest number of documentaries and short films."[16]

- Susan Solomon (known as Firoza Begum), actress in India in the 1920s and 1930s[16]

- Esther David, writer and critic

See also

References

- ↑ Fischel, Walter (1970). "Bombay in Jewish History in the Light of New Documents from the Indian Archives". Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research. 38/39: 119–144. JSTOR 3622356. (registration required (help)).

- 1 2 Weil, Shalva (2010). "Bombay". In Stillman, Norman A. Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World. Leiden: Brill.

- ↑ Weil, Shalva (1981). The Jews from the Konkan: the Bene Israel Community of India. Tel-Aviv: Beth Hatefutsoth.

- ↑ Weil, Shalva (2008). "The Jews of Pakistan". In Erlich, M. Avrum. Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora. Santa Barbara, USA: ABC CLIO.

- 1 2 Weil, Shalva (2009) [2002]. "Bene Israel Rites and Routines". In Weil, Shalva. India’s Jewish Heritage: Ritual, Art and Life-Cycle (3rd ed.). Mumbai: Marg Publications. pp. 78–89.

- ↑ Roland JG (1998) The Jewish communities of India: identity in a colonial era. 2nd ed. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers

- ↑ Weil, Shalva (1994). "Yom Kippur: the Festival of Closing the Doors". In Goodman, Hananya. Between Jerusalem & Benares: Comparative Studies in Judaism & Hinduism. New York: State University of New York Press. pp. 85–100.

- ↑ Weil, Shalva (2013). "Jews of India and Ten Lost Tribes". In Patai, Raphael; Itzhak, Haya Bar. Jewish Folklore and Traditions: A Multicultural Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO.

- ↑ Weil, Shalva (1996). "Religious Leadership vs. Secular Authority: the Case of the Bene Israel". Eastern Anthropologist. 49 (3-4): 301–316.

- ↑ "David Ezekiel Rahabi (Jewish-Indian leader)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Britannica.com. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ↑ "Bene Israel". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ↑ Shalva, Weil (2002). "Cochin Jews". In Ember, Carol R.; Ember, Melvin; Skoggard, Ian. Encyclopedia of World Cultures Supplement. New York: Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 78–80.

- ↑ Haeem Samuel Kehimkar, The History of the Bene-Israel of India (ed. Immanuel Olsvanger), Tel-Aviv : The Dayag Press, Ltd.; London : G. Salby 1937, p. 66

- ↑ Weil, Shalva. "The Bene Israel of India". The Database of Jewish Communities. Archived from the original on 7 January 2008.

- ↑ Saphir, Yaakov (1968). Even Sapir (in Hebrew). 1. Jerusalem. p. 217.

- 1 2 3 4 Menon, Harish C. (14 December 2005). "Jews, the lost tribe of Indian Cinema". IndiaGlitz.

- ↑ Religion and Society. Christian Institute for the Study of Religion and Society, Vol. 38 - India. 1991.|pages=53|note=Reference notes him as Ennoch Isaac Satamkar

- 1 2 Weil, Shalva (2008). "Jews in India". In Erlich, M. Avrum. Encyclopaedia of the Jewish Diaspora. Santa Barbara, USA: ABC CLIO.

- ↑ Roland, Joan G. (1989). Jews in British India: Identity in a Colonial Era. Hanover: University Press of New England. pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Weil, Shalva (2005). "Motherland and Fatherland as Dichotomous Diasporas: the Case of the Bene Israel". In Anteby, Lisa; Berthomiere, William; Sheffer, Gabriel. Les Diasporas 2000 ans d'histoire. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes. pp. 91–99.

- 1 2 Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Singh, Manvendra; Rai, Niraj; Kariappa, Mini; Singh, Kamayani; Singh, Ashish; Singh, Deepankar Pratap; Tamang, Rakesh; Rani, Deepa Selvi; Reddy, Alla G.; Singh, Vijay Kumar; Singh, Lalji; Thangaraj, Kumarasamy (13 January 2016). "Genetic affinities of the Jewish populations of India". 6. doi:10.1038/srep19166. PMC 4725824

. PMID 26759184.

. PMID 26759184. - 1 2 Waldman YY, Biddanda A, Davidson NR, Billing-Ross P, Dubrovsky M, Campbell CL, Oddoux C, Friedman E, Atzmon G, Halperin E, Ostrer H, Keinan A (2016)

- ↑ PLoS One 24:11(3):e0152056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152056

- ↑ Weil, Shalva. (2000) India, The Larger Immigrations from Eastern Countries, Jerusalem: Ben-Zvi Institute and the Ministry of Education. (Hebrew)

- ↑ Weil, Shalva (2011). "Bene Israel". In Baskin, Judith. Cambridge Dictionary of Judaism and Jewish Culture. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- 1 2 Abramov, S. Zalman (1976). Perpetual dilemma: Jewish religion in the Jewish State. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 277–278.

- 1 2 Smooha, Sammy (1978). Israel: Pluralism and Conflict. University of California Press. pp. 400–401.

- ↑ "How Do the Issues in the Conversion Controversy Relate to Israel?". Jcpa.org. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ↑ Weil, Shalva (2012). "The Bene Israel Indian Jewish Family in Transnational Context". Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 43 (1): 71–80.

- ↑ "Report of the High Level Commission on the Indian Diaspora" (PDF). Indian Diaspora.

- ↑ Joffe, Lawrence (9 March 2004). "Obituary: Nissim Ezekiel". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2013-09-26.

Further reading

- Esther, David. The Book of Esther, 'Penguin Global, 2003

- Isenberg, Shirley Berry. India's Bene Israel: A Comprehensive Inquiry and Sourcebook, Berkeley: Judah L. Magnes Museum, 1988

- Meera Jacob. Shulamith (1975)

- Parfitt, Tudor. (1987) The Thirteenth Gate: Travels among the Lost Tribes of Israel, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Shepard, Sadia. The Girl from Foreign: A Search for Shipwrecked Ancestors, Forgotten Histories, and a Sense of Home, Penguin Press, 2008

- Weil, Shalva. Indo-Judaic Studies in the Twenty-First Century: A Perspective from the Margin, Katz, N., Chakravarti, R., Sinha, B. M. and Weil, S. (eds) New York and Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, ISBN 978-1-4039-7629-1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bene Israel. |

- Joseph Jacobs and Joseph Ezekiel, "Beni-Israel", Jewish Encyclopedia (1901–1906)

- "Interview with Sadia Shepard", Voices on Antisemitism, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 4 June 2009

- "Bene Israel", Photo Gallery & Forum, Jews of India

- Adil Najam, "Jews in Pakistan", The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University, September 2005.

- "The Indian Jewish community and synagogues in Israel", India Jews

- "Yonati Ziv Yifatech", Bene Israel wedding hymn

- Bene Israel History

- , The History of the Bene-Israel in India, by Haeem Samuel Kahimkar (1830-1909)