Belgitude

.svg.png)

.jpg)

Belgitude is a term used to express the Belgian soul and identity.

Context

Contrary to most other countries Belgians have a mixed feeling towards their identity as one people. This is a result of being occupied by many foreign European powers throughout the centuries, which led to an inferiority complex about their status and power in the world. The regions were conquered by Romans, French, Burgondia, Spain, Austria-Hungary, the French again and finally The Netherlands before becoming independent in 1830. And even then they were occupied again by the Germans during the First World War and Second World War. Another aspect contributing to belgitude is the fact that many Belgians identify more with being Flemish, Walloon or part of Brussels, but even within those groups many feel more attached to being part of a city or province than any national or community identity. There have been countless issues between the Flemish and Walloon communities throughout Belgian history that often lead to intense political discussions and crisises in Belgian parliament.

The Belgian identity is seen as an "hollow" identity: it is defined mostly by what it is not. For example, the Belgian is neither French, Dutch or German. At the time of the term's coinage, it was not accepted by the general population, and the term seemed to have "more cultural than political weight". At the time, belgitude could be synonymous with marginality.[1] Susan Bainbrigge defines it as "a term that represents [the] new approach to francophone Belgium specificity [that emerged] in the 1970s and 1980s".[1] It involved the extent of the questioning identity of Belgians with the sense of self-mockery that characterizes them.

History of the Belgian feeling of identity

During his conquest of Gaul in 54 before Christ Julius Caesar wrote in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico about the three Celtic tribes that inhabited the country, namely the Aquitani in the southwest, the Gauls of the biggest central part, who in their own language were called Celtae, and the Belgae in the north. Caesar famously wrote that the Belgae were "the bravest of the three peoples, being farthest removed from the highly developed civilization of the Roman Province, least often visited by merchants with enervating luxuries for sale, and nearest to the Germans across the Rhine, with whom they are continually at war".[2] Despite Caesar referring to the Celtic tribe the Belgae and not modern day Belgium the quote was used a lot in Belgian history books from the 1830s on while the new independent state searched for its own identity.

The most famous quote about the Belgian identity was said by the Walloon socialist politician Jules Destrée. According to Destrée, Belgium was composed of two separate entities, Flanders and Wallonia, and a feeling of Belgian nationalism was not possible, illustrated in his 1906 work "Une idée qui meurt: la patrie" (An idea that is dying: the fatherland). In the "Revue de Belgique" of 15 August 1912 he articulated this in his famous and notorious "Lettre au roi sur la séparation de la Wallonie et de la Flandre" (Letter to the king on the separation of Wallonia and Flanders), where he wrote:

Il y a en Belgique des Wallons et des Flamands. Il n'y a pas de Belges.

In Belgium there are Walloons and Flemings. There are no Belgians.

Contrary to later interpretations Destrée didn't favor separatism, but wanted a move to a federal state. King Albert I of Belgium wrote an official answer to the letter, which read: I read the letter of Destrée, which, without uncertainty, is some literature of great talent. All that he said is absolutely true, but it is not less true that administrative separation would be an evil with more disadvantages and dangers than any aspect of the current situation.[3] In 1960 Flemish politician Gaston Eyskens modified this quote, saying "Sire, il n'y a plus de Belges" (Sire, there are no more Belgians), after the first steps were taken to transform Belgian into a federal state.

Etymology

The neologism "belgitude" was coined in 1976, by Pierre Mertens and Claude Jevaeu in as issue of the Nouvelles littéraires called "L'autre Belgique".[1] It alludes to the term négritude about feeling black, expressed by Leopold Sedar Senghor. The term caught on quick enough to be referred to in Belgian singer Jacques Brel's song "Mai 1940" ("May 1940"), which was left off his final album Les Marquises in 1977, but made available in 2003. In the song Brel refers to German soldiers who occupied Belgium during World War Two and wiped out his belgitude:

D'un ciel plus bleu qua'à l'habitude, (Translation: "From a heaven bluer than usual")

Ce mai 40 a salué (Translation: "That May 1940 greeted")

Quelques Allemands disciplinés (Translation: "Several disciplined Germans")

Qui écrasaient ma belgitude, (Translation: "Who wiped out my belgitude".) [4]

In 2012 the word "Belgitude" was listed in the French encyclopedia, the Petit Larousse [5]

Examples of belgitudes

Belgitude is characterised by things that are unique to Belgian culture, such as Belgian Dutch and Belgian French. The Dutch in Belgium has many gallicisms and the French in Belgium many hollandisms, both in terms of words as well as grammar. The word "bourgemestre" (mayor) in Wallonia, for instance, is clearly inspired by the Dutch word "burgemeester" and differs considerably from the commonly accepted French word "maire". The word "plezant" ("amusing") in Flanders is a derivation of the French word "plaisant" and is hardly used in The Netherlands.[6]

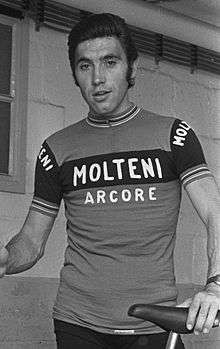

Typical foods and drinks, such as Belgian beer, moules frites, speculaas, waterzooi, witloof, Brussels sprouts, Belgian chocolate,... are also seen as examples of belgitude, because they are often promoted abroad. People who were important to Belgian history are also often cited: Ambiorix, Godfrey of Bouillon, Charles V of Spain, Adolphe Sax, Baudouin of Belgium, as are cultural icons such as Manneken Pis, the Gilles of Binche, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Peter Paul Rubens, Tintin, Inspector Maigret, the Atomium, Jacques Brel, René Magritte, Soeur Sourire, Django Reinhardt,... In the fields of sport Eddy Merckx and the Red Devils are a good example. The song "Potverdekke! (It's great to be a Belgian)" (1998) by Mr. John is also an expression of belgitude. The satirical comedy and film adaptation Sois Belge et tais-toi, the films of Jan Bucquoy and the comedy team Les Snuls are all loving and mocking tributes to the Belgian identity.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Bainbrigge, Susan (2009). Culture and identity in Belgian francophone writing: dialogue, diversity and displacement. Peter Lang. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- ↑ Julius Caesar, The Conquest of Gaul Gallico, trans. S. A. Handford, revised with a new introduction by Jane F. Gardner (Penguin Books 1982), I.1.

- ↑ (French) J'ai lu la lettre de Destrée qui, sans conteste, est un littérateur de grand talent. Tout ce qu'il dit est absolument vrai, mais il est non moins vrai que la séparation administrative serait un mal entraînant plus d'inconvénients et de dangers de tout genre que la situation actuelle. Landro, 30 août, A Jules Ingebleek, secrétaire privé du Roi et de la Reine, lettre reproduite in extenso in M-R Thielemans et E. Vandewoude, Le Roi Albert au travers de ses lettres inédites, Office international de librairie, Bruxelles, 1982, pp. 435-436.

- ↑ http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_ons003200301_01/_ons003200301_01_0174.php

- ↑ « « Belgitude » dans le Petit Larousse illustré » dans 7sur7.be, 27 juin 2011, consulté le 28 juin 2011

- ↑ http://www.vlaamsetaal.be/artikel/171/franse-invloed