Beer chemistry

The chemical compounds in beer give it a distinctive taste, smell and appearance. The majority of compounds in beer come from the metabolic activities of plants and yeast and so are covered by the fields of biochemistry and organic chemistry.[1] The main exception is that beer contains over 90% water and the mineral ions in the water (hardness) can have a significant effect upon the taste.[2]

Ingredients

Four main ingredients are used to make beer in the process of brewing.

Carbohydrate

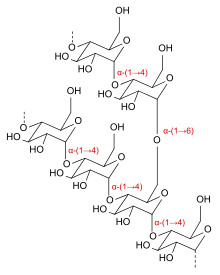

The carbohydrate source is an essential part of the beer because unicellular yeast organisms convert carbohydrates into energy to live. Yeast metabolize the carbohydrate source to form a number of compounds including ethanol. The process of brewing beer starts with malting and mashing, which breaks down the long carbohydrates in the barley grain into more simple sugars. This is important because yeast can only metabolize very short chains of sugars.[3] Long-carbohydrates are polymers, large branching linkages of the same molecule over and over. In the case of barley, we mostly see polymers called amylopectin and amylose which are made of repeating linkages of glucose. On very large time-scales (thermodynamically) these polymers would break down on their own, and there would be no need for the malting process.[4] However, the average brewer does not have years to wait, and so he speeds up this process by heating up the barley grain.[3] This heating process activates protein enzymes called amylases. The shape of these enzymes, their active site, gives them the unique and powerful ability to speed these degradation reactions to over 100,000 times faster. The reaction that takes place at the active site is called a hydrolysis reaction, which is a cleavage the linkages between the sugars. Repeated hydrolysis breaks the long amylopectin polymers into simpler sugars that can be digested by the yeast.[4]

Hops

Hops are the flowers of the hops plant Humulus lupulus. These flowers contain over 250 essential oils, which contribute to the aroma and non-bitter flavors of beer.[4] However, that distinct bitterness especially characteristic of pale ales comes from a family of compounds called alpha-acids (also called humulones) and beta-acids (also called lupulones). Generally, brewers believe that α-acids give the beer a pleasant bitterness whereas β-acids are considered less pleasant.[4] α-acids isomerize during the boiling beer boiling process in the reaction pictured. The six-member ring in the humulone isomerizes to a five-member ring, but it is not commonly discussed how this affects perceived bitterness.

Yeast

In beer, the metabolic waste of yeast is a significant factor. In aerobic conditions, the yeast will use the simple sugars from the malting process in glycolysis, and send the major organic product of glycolysis (pyruvate) into carbon dioxide and water via cellular respiration, many homebrewers use this aspect of yeast metabolism to carbonate their beers. However, under anaerobic conditions yeast cannot use the end products of glycolysis to generate energy in cellular respiration. Instead, they rely on a process called fermentation. Fermentation converts pyruvate into ethanol through the intermediate acetaldehyde.

Water

Water can often play a very important role in the way a beer tastes,[2][4] as beer is around 90% water and different brands of water can taste different. Further, the ion species present in the water can affect the metabolic pathways of yeast. For example, calcium and iron are essential in small amounts for yeast to survive in water, because these metals are usually required cofactors for yeast enzymes.[4]

Storage and degradation

A particular problem with beer is that, unlike wine, its quality tends to deteriorate as it ages. A cat urine smell and flavor called ribes, named for the genus of the black currant, tends to develop and peak.[6] A cardboard smell then dominates which is due to the release of 2-Nonenal.[7] In general, chemists believe that the "off-flavors" that come from old beers are due to reactive oxygen species. These may come in the form of oxygen free radicals, for example, which can change the chemical structures of compounds in beer that give them their taste.[7]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Barth 2013, p. 9,89.

- 1 2 Barth 2013, p. 69-88.

- 1 2 Barth 2013, p. 144.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Janson 1996.

- ↑ Marnett, Alan, The Chemistry of Skunky Beer

- ↑ Barth 2013, p. 231.

- 1 2 Bart Vanderhaegen; Hedwig Neven; Hubert Verachtert; Guy Derdelinckx (2006), "The chemistry of beer aging – a critical review", Food Chemistry, vol. 95 (3): 357–381, doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.01.006, ISSN 0308-8146

Sources

- Barth, Roger (2013), The Chemistry of Beer: The Science in the Suds, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-1-11873-379-0

- Baxter, Denise; Hughes, Paul (2001), Beer: Quality, Safety and Nutritional Aspects, Royal Society of Chemistry, ISBN 978-0-85404-588-4

- Hopkins, R (2011), Biochemistry Applied to Beer Brewing – General Chemistry of the Raw Materials of Malting and Brewing, Tobey Press, ISBN 978-1-44654-168-5

- Hornsey, Ian (2003), A History of Beer and Brewing, Royal Society of Chemistry, ISBN 978-0-85404-630-0

- Janson, Lee (1996), Brew Chem 101, Storey, ISBN 978-0-88266-940-3

- Verhagen, Leen (2010), "Beer Flavor", Comprehensive Natural Products II: Chemistry and Biology, Newnes, Vol. 3: Development & Modification of Bioactivity, pp. 967–998, ISBN 978-0-08045-382-8

- Verzele, M; De Keukeleire, D (2013), Chemistry and Analysis of Hop and Beer Bitter Acids, Elsevier, ISBN 978-1-48329-086-7

External links

- Tapping into the Chemistry of Beer and Brewing — an online lecture by Charles Bamforth, Professor of Malting & Brewing Sciences at the University of California

- Chemistry of Beer — an online course in the subject at the University of Oklahoma