Battle of Liège

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

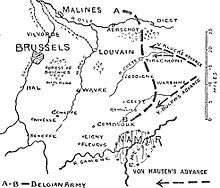

The Battle of Liège (French: Bataille de Liège) was the opening engagement of the German invasion of Belgium and the first battle of World War I. The attack on Liège city began on 5 August 1914 and lasted until 16 August, when the last fort surrendered. The length of the siege of Liège may have delayed the German invasion of France by 4–5 days. Railways needed by the German armies in eastern Belgium were closed for the duration of the siege and German troops did not appear in strength before Namur until 20 August.

Background

Strategic developments

Belgium

Belgian military planning was based on an assumption that other powers would eject an invader. The likelihood of a German invasion did not lead to France and Britain being seen as allies or for the Belgian government to intend to do more than protect its independence. The Anglo-French Entente (1904) had led the Belgians to perceive that the British attitude to Belgium had changed and that it was seen as a British protectorate. A General Staff was formed in 1910 but the Chef d'État-Major Général de l'Armée (Chief of the General Staff), Lieutenant-Général Harry Jungbluth was retired on 30 June 1912 and not replaced until May 1914 by Lieutenant-General Chevalier de Selliers de Moranville who began planning for the concentration of the army and met railway officials on 29 July. Belgian troops were to be massed in central Belgium, in front of the National redoubt of Belgium ready to face any border, while the Fortified Position of Liège and Fortified Position of Namur were left to secure the frontiers. On mobilization, the King became Commander-in-Chief and chose where the army was to concentrate. Amid the disruption of the new rearmament plan, the disorganised and poorly trained Belgian soldiers would benefit from a central position, to delay contact with an invader but it would also need fortifications for defence, which were on the frontier. A school of thought wanted a return to a frontier deployment in line with French theories of the offensive. Belgian plans became a compromise in which the field army concentrated behind the Gete river with two divisions forward at Liège and Namur.[5]

Germany

German strategy had given priority to offensive operations against France and a defensive posture against Russia since 1891. German planning was determined by numerical inferiority, the speed of mobilisation and concentration and the effect of the vast increase of the power of modern weapons. Frontal attacks were expected to be costly and protracted, leading to limited success, particularly after the French and Russians modernised their fortifications on the frontiers with Germany. Alfred von Schlieffen, Chief of the Imperial German General Staff (Oberste Heeresleitung, OHL) from 1891–1906, devised a plan to evade the French frontier fortifications with an offensive on the northern flank, which would have a local numerical superiority and obtain rapidly a decisive victory. By 1898–1899, such a manoeuvre was intended to pass swiftly through Belgium, between Antwerp and Namur and threaten Paris from the north.[6] Helmuth von Moltke the Younger succeeded Schlieffen in 1906 and was less certain that the French would conform to German assumptions. Moltke adapted the deployment and concentration plan, to accommodate an attack in the centre or an enveloping attack from both flanks as variants, by adding divisions to the left flank opposite the French frontier, from the c. 1,700,000 men which were expected to be mobilised in the Westheer (western army). The main German force would still advance through Belgium to attack southwards into France, the French armies would be enveloped on their left and pressed back over the Meuse, Aisne, Somme, Oise, Marne and Seine rivers, unable to withdraw into central France. The French would either be annihilated by the manoeuvre from the north or it would create conditions for victory in the centre or in Lorraine on the common border.[7]

Declarations of war

At midnight on 31 July – 1 August, the German government sent an ultimatum to Russia and announced a state of "Kriegsgefahr" during the day; the Turkish government ordered mobilisation and the London Stock Exchange closed. On 1 August the British government ordered the mobilisation of the navy, the German government ordered general mobilisation and declared war on Russia. Hostilities commenced on the Polish frontier, the French government ordered general mobilisation and next day the German government sent an ultimatum to Belgium, demanding passage through Belgian territory, as German troops crossed the frontier of Luxembourg. Military operations began on the French frontier, Libau was bombarded by a German light cruiser SMS Augsburg and the British government guaranteed naval protection for French coasts. On 3 August the Belgian Government refused German demands and the British Government guaranteed military support to Belgium, should Germany invade. Germany declared war on France, the British government ordered general mobilisation and Italy declared neutrality. On 4 August the British government sent an ultimatum to Germany and declared war on Germany at midnight on 4–5 August, Central European Time. Belgium severed diplomatic relations with Germany and Germany declared war on Belgium. German troops crossed the Belgian frontier and attacked Liège.[8]

Tactical developments

The Fortified Position of Liège

Liège is situated at the confluence of the Meuse, which at the city flows through a deep ravine and the Ourthe, between the Ardennes to the south and Maastricht (in the Netherlands) and Flanders to the north and west. The city lies on the main rail lines from Germany to Brussels and Paris, which von Schlieffen and von Moltke planned to use in the invasion of France. Much industrial development had taken place in Liège and the vicinity, which presented an obstacle to an invading force. The main defences were in the Position fortifiée de Liège (Fortified Position of Liège), a ring of twelve forts 6–10-kilometre (3.7–6.2 mi) from the city, built in 1892 by Henri Alexis Brialmont, the leading fortress engineer of the nineteenth century. The forts were sited about 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) apart to be mutually supporting but had been designed for frontal, rather than all-round defence.[9]

The forts were triangular or quadrangular and built of concrete, with a surrounding ditch and barbed-wire entanglements. The superstructures were buried and only mounds of concrete or masonry and soil were visible. The forts were armed with 18 × 210-millimetre (8.3 in) howitzers mounted in single gun turrets, 24 × 150-millimetre (5.9 in) guns mounted in 12 × twin turrets, 36 × 120-millimetre (4.7 in) guns distributed between 12 single and 12 twin turrets and 128 × 57-millimetre (2.2 in) quick-firers, of which 42 were mounted in single gun turrets, while the other 86 were in casements along the sides of the forts.[10] There were three patterns of fort and Fort de Lixhe was never completed and had no armament, leading to it being occupied without resistance by a German dragoon squadron.[11][12] Forts de Barchon, Boncelles, Flemalle, Fleron, Loncin and Pontisse each had 2 × 2.1 cm single turrets, a twin 15 cm turret, 2 × twin 12 cm turrets, 4 × single 5.7 cm turrets and 8 × 5.7mm in casements. Fort de Chaudfontaine/Rochette was similar but had only a 2.1 cm turret, 3 × 5.7 cm turrets and the two 12 cm turrets had a gun each. Forts de Embour, Évegnée, Hollogne, Lantin and Liers were like Chaudfontaine but had only 6 × 5.7 cm casement mounts each.[13] Each fort had retractable cupolas, mounting guns up to 6-inch (150 mm) and the main guns were mounted in steel turrets with 360° traverse but only the 57-millimetre (2.2 in) turret could be elevated. The forts contained magazines for the storage of ammunition, crew quarters for up to 500 men and electric generators for lighting. Provision had been made for the daily needs of the fortress troops but the latrines, showers, kitchens and the morgue had been built in the counterscarp, which could become untenable if fumes from exploding shells collected in the living quarters and support areas as the forts were ventilated naturally.[14]

The forts were not linked and could only communicate by telephone and telegraph, the wires for which were not buried. Smaller fortifications and trench lines in the gaps between the forts, had been planned by Brialmont but had not been built by 1914. The fortress troops were not at full strength and many men were drawn from local guard units, who had received minimal training, due to the reorganisation of the Belgian army begun in 1911, which was not due to be complete until 1926.[15] The forts also had c. 26,000 soldiers and 72 field guns of the 3rd Infantry Division and 15th Infantry Brigade to defend the gaps between forts, c. 6,000 fortress troops and members of the paramilitary Garde Civique, equipped with rifles and machine-guns.[16] The garrison of c. 32,000 men and 280 guns, was insufficient to man the forts and field fortifications. In early August 1914, the garrison commander was unsure of the troops which he would have at his disposal, since until 6 August it was possible that all of the Belgian army would advance towards the Meuse.[9]

The terrain in the fortress zone was difficult to observe, because many ravines ran between the forts. Interval defences had been built just before the battle but were insufficient to stop German infiltration. The forts were also vulnerable to attack from the rear, the direction from which the German bombardments were fired. The forts had been built to withstand shelling from 210-millimetre (8.3 in) guns, which were the largest mobile artillery in 1890 but concrete used in construction was not of the best quality and by 1914 the German army had obtained much larger 420mm howitzers, (L/12 420-millimetre (17 in) M-Gerät 14 Kurze Marine-Kanone) and Austrian 305 mm howitzers (Mörser M. 11).[17] The Belgian 3rd Division (Lieutenant-General Gérard Léman) along with the attached 15th Infantry Brigade defended Liège.[12][18] Within the division, there were five brigades and various other formations with c. 32,000 troops and 280 guns.[18][lower-alpha 1]

The Army of the Meuse

The Army of the Meuse consisted of the 11th Brigade of III Corps (Major-General von Wachter), the 14th Brigade of IV Corps (Major-General von Wussow), the 27th Brigade of VII Corps (Colonel von Massow), the 34th Brigade of IX Corps (Major-General von Kraewel), the 38th Brigade of X Corps (Colonel von Oertzen) and the 43rd Brigade of XI Corps (Major-General von Hülsen).[18] The cavalry component consisted of Höherer Kavallerie-Kommandeur II (II Cavalry Corps, Lieutenant-General Georg von der Marwitz), consisting of the 2nd (Major-General Von Krane), 4th (Lieutenant-General Von Garnier) and the 9th (Major-General Von Bulow) cavalry divisions.[19][lower-alpha 2] The Army of the Meuse (General von Emmich) had c. 59,800 troops with 100 guns and howitzers, accompanied by Erich Ludendorff as an observer for the General Staff.[9]

Prelude

German offensive preparations

In August 1914 it was realised that the garrison at Liège would be larger than anticipated and that prompt mobilisation had given the Belgians time to make progress on the defences between the forts. Six reinforced brigades and II Cavalry Corps under the X Corps commander, General Otto von Emmich were to be ready on 4 August the third day of mobilisation, at Aachen/Aix-la-Chapelle, Eupen and Malmédy to conduct the coup de main. The 2nd Army Quartermaster General, Major-General Erich Ludendorff, was assigned to the X Corps staff as he was familiar with the plan, having been the Chief of the Deployment Department of the General Staff. On the night of 5/6 August the force was to make a surprise attack, penetrate the fortress ring and capture the town, road and rail facilities. The invasion began on 4 August and aeroplanes, cavalry and cyclists went ahead of the infantry, with leaflets requesting calm from Belgian civilians. On the right flank, II Cavalry Corps with the cavalry Division Garnier and the 34th Infantry Brigade, advanced to take the crossings over the Meuse at Visé, to reconnoitre towards Brussels and Antwerp and prevent the Belgian army from interfering with the attack on Liège.[20]

The advance into Belgium took place in suffocatingly hot weather and was slowed by roadblocks; cavalry found that the bridge at Visé had been blown and were engaged by small-arms fire from the west bank. Jäger pushed the Belgians out of the village but the bridging train of the 34th Brigade was delayed and fire from the Liège forts made the area untenable. The 27th, 14th and 11th brigades reached their objectives from Mortroux to Julémont, Hervé and Soiron. The 9th Cavalry Division followed by the 2nd and 4th Cavalry divisions, advanced south of the Vesdre river, though many obstructions, gained footholds over the Ourthe and captured the bridge at Poulseur. The 38th Brigade reached Louveigne and Theux and the 43rd Brigade reached Stoumont and La Gleize. During a night made difficult by sniping from "civilians" and bombardment by the forts, the brigades prepared to close up to the jumping-off points for the attack next day. The cavalry of Division Garnier was unable to cross the river at Lixhe until 5:00 a.m., due to artillery fire from Liège and the 34th Brigade managed to cross by 10:30 p.m., only by leaving behind the artillery and supplies.[21]

The 27th Brigade reached its jumping-off positions from Argeteau to St. Remy and La Vaux and had mortars commence firing at the forts in the afternoon; an attack on fort Barchon was repulsed. The 14th and 11th brigades reached their objectives, with some fighting at Forêt and in the south, the 9th Cavalry Division rested its horses and held the crossings of the Ourthe and Amblève. Guarding the attacking corps from cavalry reported to be between Huy and Durbuy, rather than push on to take the Meuse crossings between Liège and Huy; the southern brigades closed up to the Ourthe at Esneux, Poulseur and Fraiture.[21] By the evening of 5 August, the coup de main was ready but it was obvious that no surprise could be obtained, given the resistance of the Belgian army "and civilians" in densely populated country, where movement had been slowed by hedges and fences. An envoy was sent to the fortress commander in Liège who replied with "Frayez-vous le passage" (You must fight your way through.). Emmich considered that delay would benefit the defenders and continued with the plan for a swift attack.[22]

Belgian defensive preparations

On 30 July the Chief of the Belgian General Staff, proposed to implement a plan to counter a violation of Belgian territory by the German army, by assembling the field army astride the Gete river between Hannut, St. Trond, Tirlemont, Hamme and Mille. The king rejected this as it was directed only at a German invasion and ordered a deployment further west from Perwez, Tirelemont, Louvain and Wavre. On 1 August the Belgians decided to place a division each in Liège and Namur and on 3 August the two fortresses were left to resist an invasion as best they could, while the rest of the field army protected Antwerp and waited for intervention by France and Britain, the other guarantors of Belgian neutrality.[23] At Liège, Léman had the 3rd Division and the 15th Brigade of the 4th Division, which had arrived from Huy on the night of 5/6 August and increased the garrison to c. 30,000 men. Léman deployed the infantry against attacks from the east and south.[24]

Plan of attack

The terrain and fortresses at Liège favoured an attack by coup de main because the gaps between the forts had not been maintained and some areas were cut by deep ravines immune to bombardment by the fortress artillery. The General Staff assumed a Belgian garrison of 6,000 men in peacetime with c. 3,000 members of the Garde Civique.[lower-alpha 3] The plan required the 34th Brigade to attack between forts Loncin and Pontisse, the 27th Brigade to break through between the Meuse and fort Evegnée on the east bank, the 14th Brigade to penetrate between forts Evegnée and Fléron and the 11th Brigade between Fléron and Chaudfontaine, as the 38th and 43rd brigades attacked between the Ourthe and Meuse; the II Cavalry Corps was to envelop the fortress and assemble to the north-west. The terrain made an advance across country impracticable so the attackers were to form marching columns behind vanguards, with slung rifles only to be used on officers orders, white armbands and a password, ("Der Kaiser") were to be used for recognition. The outer fortress defences were to be bypassed in the dark so that Liège could be attacked during the day.[22]

Battle

German attack, 6–7 August

In the north, the 34th Brigade under Major-General von Kraewel had eight battalions less their artillery, as the rest of the brigade was on the far side of the Meuse being ferried over. The attack began at 2:30 a.m. from Hermée and was bombarded with shrapnel, which disorganised the infantry. A battalion turned against Pontisse and the rest fought their way into Herstal, where a house-to-house fight against Belgian troops "and civilians" began and then took Préalle under flanking fire from Liers and Pontisse.[lower-alpha 4] Troops under Major von der Oelsnitz got into Liège and nearly captured General Léman, the Military Governor before being killed or captured. By dawn the brigade was on high ground north-west of Herstal, with its units mixed up and having had many casualties. Belgian troops counter-attacked from Liège and the troops were bombarded by Liers and Pontisse until 10:15 a.m. when Kraewel ordered a retreat, which had to run the gauntlet between the forts and suffered many more casualties. The retreat continued all the way back to the Meuse at Lixhe, with losses of 1,180 men.[27]

.jpg)

The advance of the 27th Brigade under Colonel von Massow was hemmed in by houses, hedges and fences, which made flanking moves extremely difficult. The force was heavily bombarded by forts Wandre and Barcheron, at a defensive position beyond Argenteau, where disorganisation and confusion led to the Germans firing on each other as well as the Belgians. By dawn the brigade had reached fort Wandre but the arrival of Belgian reinforcements led Massow to order a withdrawal to Argenteau. On the left a second column was held up at Blegny, east of fort Barcheron and retired to Battice when the fate of the other columns became known. To the south-east the 11th Brigade under Major-General von Wachter attacked through St. Hadelin and Magnée, where it was also compressed into a narrow column by buildings along the road. Small-arms fire forced the Germans between the houses and delayed the advance, which did not reach Romsée until 5:30 a.m. where the Belgian 14th Regiment had been able prepare defences. The Belgians were defeated but only after artillery had been brought forward and the advance towards Beyne-Heusay bogged down.[lower-alpha 5] Uncertainty about the flanks led Wachter to order a retirement to ravines east of Magnée, to find cover from bombardment by forts Pieron and Chaudfontaine.[28]

| Liège Forts (Clockwise from N) |

|---|

| Liers |

| Pontisse |

| Barchon |

| Évegnée |

| Fleron |

| Chaudfontaine |

| Embourg |

| Boncelles |

| Flémalle |

| Hollogne |

| Loncin |

| Lantin |

South of the Vesdre, the 38th Brigade advance began on 5 August at 8:00 p.m. with the 43rd Brigade in reserve. The attackers were severely bombarded while still on the start-line and a thunderstorm, road blocks and difficult forest paths made things worse. At Esneux and Poulseur, German supplies were looted "by Belgian civilians" and had to be rescued. An engagement began in woods east of fort Boncelles and Belgian small-arms fire wounded the commander Major-General von Hülsen, hit the rear of the column and threw it into confusion. The Belgian defences were captured by morning but the brigades had become mingled; Boncelles village was captured but fire from the fort forced the Germans into woods to the north-west. Attacks were made later against high ground south and south-west of Ougrée. Skirmishing went on all day, with many casualties around fort Boncelles and as ammunition ran short the 43rd Brigade retreated to Fontin, as the 38th Brigade conformed and withdrew to Lince. The attacks from the north and south had failed and an attack by Zeppelin Z-VI from Cologne, at 3:00a.m. had little effect. The airship had been fired on by the Belgian artillery and was wrecked near Bonn, making a forced-landing due to loss of gas.[29]

In the centre the 14th Brigade advanced at 1:00 a.m., led by Emmich and Ludendorff and made a rapid advance to Retinne, where Belgian troops covered the road with machine-guns and forced the Germans under cover with many casualties. The brigade commander Major-General von Wussow and a regimental commander were wounded, which led Ludendorff to take over and rally the survivors. The Belgians were outflanked and c. 100 prisoners taken. At Queue-du-Bois the advance was stopped in house-to-house fighting, until two howitzers were brought up and the village was eventually taken around dawn. By noon the brigade reached high ground near a Carthusian convent and saw a white flag flying on the Citadel over the river. An officer was sent forward to investigate and found that the flag had been unauthorised and was repudiated by Léman. Attempts were made to contact flanking units but communications to the rear had been cut and no ammunition had been delivered, which left the force of c. 1,500 men isolated during the night.[30] During the morning, Emmich gambled that the bridges in Liège were undefended and ordered the town to be occupied. Infantry Regiment 165 crossed the river and reached the north-western gate without resistance, taking several parties of Belgian infantry prisoner. Ludendorff drove ahead of Infantry Regiment 27, under the impression that the Citadel had been captured, found himself alone with the garrison and bluffed them into surrender. The town and the Meuse bridges had been captured with most railway lines intact. Emmich sent officers to make contact with the other brigades; the 11th Brigade advanced at noon and reached Liège, through artillery-fire from fort Chaudfontaine by evening and formed a defensive line along the west side of the town. The 27th, 24th brigades and the rest of the 11th Brigade entered the town and operations began to capture the forts.[31]

Belgian defence, 6–7 August

In the morning of 5 August Captain Brinckman, the Military Attaché of the German Empire at Brussels, met the Governor of Liège under a flag of truce and demanded the surrender of the fortress.[32] Léman refused and an attack began on the east bank forts of Chaudfontaine, Fléron, Évegnée, Barchon and Pontisse, an hour later. An attack on the Meuse, below the junction with the Vesdre, failed. Between Fort Barchon and the Meuse, the Germans briefly penetrated the line but were forced back by a counter-attack of the 11th Brigade. In the late afternoon and during the night the German infantry attacked in five columns, two from the north, one from the east and two from the south. Although the attacks were supported by heavy artillery, the German infantry were repulsed with great loss.[19] The attack at the Ourthe forced back the defenders between the forts, before counter-attacks by the 12th, 9th and 15th Brigades checked the German advance.[33] Just before dawn, a small German raiding party tried to abduct the Governor from the Belgian Headquarters in Rue Ste. Foi. Alarmed by gunfire in the street, Léman and his staff rushed outside and joined the guard platoon fighting the raiding party, which was driven off with twenty dead and wounded left behind.[34]

German cavalry moved south from Visé to encircle the town and German cavalry patrols had been operating up to 20 km west of Liege, leading Léman to believe that the German II Cavalry Corps was encircling the fortified area from the north, though in fact the main body of that force was still to the east, and would not begin to cross the Meuse until 8 August, when the reservists had arrived.[35] Believing he would be trapped, he decided that the 3rd Infantry Division and 15th Infantry Brigade should withdraw westwards to the Gete, to join the Belgian field army.[36] On 6 August, the Germans carried out the first air attack on a European city, when a Zeppelin airship bombed Liège and killed nine civilians.[9] Léman believed that units from five German corps confronted the defenders and assembled the 3rd Division between forts Loncin and Hollogne to begin the withdrawal to the Gete during the afternoon and night of the 6th.[12] The fortress troops were concentrated in the forts, rather than the perimeter and Léman set up a new headquarters at noon in Fort Loncin, on the western side of the city.[37] German artillery bombarded the forts and Fort Fléron was put out of action, when its cupola-hoisting mechanism was destroyed by shell fire.[38] On the night of 6/7 August German infantry were able to advance between the forts and during the early morning of 7 August, General Ludendorff took command of the attack, ordered up a field howitzer and fought through the village of Queue-du-Bois to high ground, which overlooked Liège and captured the Citadel of Liège. Ludendorff sent a party forward to Léman under a flag of truce, to demand surrender but Léman refused.[39]

Siege

8–16 August

Bülow gave command of the siege operations at Liège to General Karl von Einem, the VII Corps commander with the IX and X Corps under his command. The three corps were ordered over the Belgian border on 8 August. At Liège, on 7 August, Emmich sent liaison officers to make contact with the brigades scattered around the town. The 11th Brigade advanced into the town and joined the troops there on the western fringe. The 27th Brigade arrived by 8 August, along with the rest of the 11th and 14th brigades. Fort Barcheron fell after a bombardment by mortars and the 34th Brigade took over the defence of the bridge over the Meuse at Lixhe. On the southern front the 38th and 43rd Brigades retreated towards Theux, after a false report that Belgian troops were attacking from Liège and Namur. On the night of 10/11 August Einem ordered that Liège be isolated on the eastern and south-eastern fronts by the IX, VII and X corps as they arrived and allotted the capture of forts Liers, Pontisse, Evegnée and Fléron to IX Corps and Chaudfontaine and Embourg to VII Corps as X Corps guarded the southern flank.[40]

Before the orders arrived, fort Evegnée was captured after a bombardment. IX Corps isolated fort Pontisse on 12 August and began a bombardment of forts Pontisse and Fléon during the afternoon, with 380-millimetre (15 in) coastal mortars and Big Bertha 420-millimetre (17 in) siege howitzers. The VII Corps heavy artillery began to fire on fort Chaudfontaine, fort Pontisse was surrendered and IX Corps crossed the Meuse to attack fort Liers.[40] Fort Liers fell in the morning of 14 August and the garrison of fort Fléron surrendered in the afternoon, after a Minenwerfer bombardment. The X Corps and the 17th Division were moved to the north and VII Corps to the south of the Liège–Brussels railway and on 15 August, a bombardment began on the forts to the west of the town. Fort Boncelles fell in the morning and fort Lantin in the afternoon; fort Loncin was devastated by the 420mm guns and Léman was captured. Forts Hollogne and Flémalle were surrendered on the morning of 16 August after a short bombardment.[41]

Aftermath

Analysis

.jpg)

By the morning of 17 August, the German 1st Army, 2nd Army and 3rd Army were free to resume their advance to the French frontier. The Belgian field army withdrew from the Gete towards Antwerp from 18–20 August and Brussels was captured unopposed on 20 August.[39] The siege of Liège had lasted for eleven days, rather than the two days anticipated by the Germans. For 18 days, Belgian resistance in the east of the country had delayed German operations, which gave an advantage to the Franco-British forces in northern France and in Belgium. In Graf Schlieffen und der Weltkrieg (1921) Wolfgang Förster wrote that the German time-table of deployment had required its armies to reach a line from Thionville to Sedan and Mons by the 22nd day of mobilisation (23 August), which was achieved ahead of schedule. In Bulletin Belge des Sciences Militaires (September 1921), a four-day delay was claimed.[39] John Buchan wrote

The triumph was moral — an advertisement to the world that the ancient faiths of country and duty could still nerve the arm for battle, and that the German idol, for all its splendour, had feet of clay.— John Buchan[42]

In the first volume of Der Weltkrieg (1925), the German official historians wrote that the Battle of Liège had ended just in time for the German armies to begin their march up the Meuse valley. The Aix-la-Chapelle–Liège railway line was operational by 15 August, although repairs had been necessary at the Nasproue tunnel and the line at Verviers, where 17 locomotives had been crashed together. The efforts of the 14th Brigade, Emmich and Ludendorff were commended and the value of the super-heavy artillery was noted.[43] In 1926 J. E. Edmonds, the British official historian, recorded that General Alexander von Kluck had considered that a delay of 4–5 days had been caused by the resistance of the Liège garrisons.[39] The most advanced corps of the 1st Army, reached a line from Kermt to Stevoort and Gorsem, 40 miles (64 km) west of Aachen (Aix La Chapelle), from 7–17 August and the resistance of the Liège garrisons, may have stopped the Germans from reaching the area by 10 August. General Karl von Bülow, commander of the German 2nd Army, wrote that Liège had been besieged by six composite brigades and a cavalry corps and on 10 August, OHL had hoped to begin the advance to the French border three days later but that the siege delayed the march until 17 August.[39]

In 1934 the British historian, Charles Cruttwell, wrote of "brave Belgian resistance" at Liège, which surprised the Germans but did not interfere with their plans and that demolitions of railway tunnels and bridges were a more serious cause of delay.[44] Sewell Tyng wrote in 1935, that the southward advance of the German armies had begun on 14 August, after all of the forts on the right bank had fallen. The eleven-day siege had come as a "bitter disappointment" to the German commanders, there had been failures of co-ordination, which had led to several incidents of German infantry firing on each other. Little liaison had taken place between the infantry and their commanders and attacking before the super-heavy artillery was ready, had caused a disproportionate number of casualties. Tyng wrote that the delay imposed on the Germans was about 48 hours, although various authorities had claimed anything from no delay to five days.[45] In 2001, Hew Strachan wrote that the German advance had been delayed by 48 hours, because the concentration of German active corps had taken until 13 August.[46] Liège was awarded the French Légion d'honneur in 1914. The effect of German and Austrian super-heavy artillery on French and Belgian fortresses in 1914, led to a loss of confidence in fortifications; much of the artillery of fortress complexes in France and Russia was removed to reinforce field armies. At the Battle of Verdun in 1916, the resilience of French forts proved to have been underestimated.[47]

Casualties

In 2009 Herwig wrote that the Belgian army had 20,000 casualties at Liège and that by 8 August the German attack had cost 5,300 men.[48] Other sources give 2,000–3,000 Belgian killed or wounded and 4,000 prisoners.[49]

Subsequent operations

On 5 August the 4th Division at the Fortified Position of Namur, received notice from Belgian cavalry units, that they were in contact with German cavalry to the north of the fortress. More German troops appeared to the south-west on 7 August. On 7 August OHL had ordered the 2nd Army units assembled near the Belgian border, to advance and send mixed brigades from the IX, VII and X corps to Liège immediately.[50] Large numbers of German troops did not arrive in the vicinity of Namur until 19–20 August, too late to forestall the arrival of the 8th Brigade, which having been isolated at Huy, had blown the bridge over the Meuse on 19 August and retired to Namur. During the day the Guards Reserve Corps of the German 2nd Army arrived to the north of the fortress zone and the XI Corps of the 3rd Army, with the 22nd Division and the 38th Division, arrived to the south-east.[51]

A siege train including one Krupp 420-millimetre (17 in) howitzer and four Austrian 305-millimetre (12.0 in) mortars, accompanied the German troops and on 20 August, Belgian outposts were driven in; next day the German super-heavy guns began to bombard the eastern and south-eastern forts. The Belgian defenders had no means of keeping the German siege guns out of range or engaging them with counter-battery fire, by evening two forts had been seriously damaged and after another 24 hours the forts were mostly destroyed. Two Belgian counter-attacks on 22 August were defeated and by the end of 23 August, the northern and eastern fronts were defenceless, with five of the nine forts in ruins. The Namur garrison withdrew at midnight to the south-west and eventually managed to rejoin the Belgian field army at Antwerp; the last fort was surrendered on 25 August.[51]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The 9th Mixed Brigade, including the 9th and 29th Regiments of the Line, along with the 43rd, 44th, and 45th Artillery Batteries. The 11th Mixed Brigade with the 11th and 31st Regiments of the Line and the 37th, 38th, and 39th Artillery Batteries. The 12th Mixed Brigade, including the 12th and 32nd Regiments of the Line, along with the 40th, 41st, and 42nd Artillery Batteries, the 14th Mixed Brigade with the 14th and 34th Regiments of the Line, and the 46th, 47th, and 48th Artillery Batteries and the 15th Mixed Brigade from 5 August, with the 1st and 4th Chasseurs à Pied Regiments, along with the 61st, 62nd, and 63rd Artillery Batteries. The Fortress Guards comprised the 9th, 11th, 12th, and 14th Reserve Infantry Regiments, an artillery regiment, four reserve batteries and various other troops, the 3rd Artillery Regiment and the 40th, 49th and 51st Artillery Batteries with the 3rd Engineer Battalion and the 3rd Telegraphist Section. The cavalry component was the 2nd Regiment of Lancers.[18]

- ↑ German Cavalry Corps were not army corps in the conventional sense but were the largest German cavalry units that operated in 1914 and were known as Höherer Kavallerie-Kommandeur, the unit in this case being HKK II.

- ↑ Garde Civique was a militia, active in cities with a population of more than 10,000 people, in fortified towns and those near border fortresses. All males from 21–50 were members with duties of "maintaining law and order and protecting the independence and territorial integrity of Belgium". The Garde was mobilised on 5 August and civilians were notified that armed resistance could only be shown by those wearing official badges.[25]

- ↑ Kraewel ordered the houses to be burnt down during the retreat and claimed that the entire population had participated in the fighting. Next day the Germans killed 27 civilians in the town. From 4–7 August, the 34th Brigade murdered at least 117 Belgian civilians.[26]

- ↑ At St. Hadelin on 6 August, the Germans killed 104 civilians, burned down Magnée and used 200 civilians from Romsée and Olne as human shields during an attack on forts Embourg and Chaudfontaine.[26]

Footnotes

- ↑ Zuber 2010, pp. 18–19, 41–42, 44, 83.

- ↑ Zuber 2010, pp. 74, 84.

- ↑ http://www.fortiff.be/ifb

- ↑ Zuber 2010, p. 86.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 209–211.

- ↑ Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 66, 69.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 190, 172–173, 178.

- ↑ Skinner & Stacke 1922, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 Strachan 2001, p. 211.

- ↑ http://www.fortiff.be/ifb

- ↑ http://www.fortiff.be/ifb/index.php?page=l5

- 1 2 3 Zuber 2010, p. 83.

- ↑ http://www.fortiff.be/ifb

- ↑ Donnell 2007, p. 36.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 210.

- ↑ Zuber 2010, pp. 74, 83.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 212.

- 1 2 3 4 Vermeulen 2000, p. a.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1926, p. 32.

- ↑ Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 96–97.

- 1 2 Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 97–98.

- 1 2 Humphries & Maker 2013, p. 99.

- ↑ Humphries & Maker 2013, p. 80.

- ↑ Humphries & Maker 2013, p. 104.

- ↑ Humphries & Maker 2013, p. 96.

- 1 2 Humphries & Maker 2013, p. 100.

- ↑ Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 101–102.

- ↑ Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 102–103.

- ↑ Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 103–105.

- ↑ Tyng 1935, p. 53.

- ↑ General Staff 1915, p. 12.

- ↑ Tyng 1935, p. 54.

- ↑ Zuber 2010, pp. 85, 93.

- ↑ Edmonds 1926, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ General Staff 1915, p. 13.

- ↑ Keegan 2000, pp. 84–85.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Edmonds 1926, p. 33.

- 1 2 Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 105–106.

- ↑ Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Buchan 1921, p. 134.

- ↑ Humphries & Maker 2013, p. 107.

- ↑ Cruttwell 1934, p. 15.

- ↑ Tyng 1935, pp. 57–59.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 121.

- ↑ Edmonds 1926, p. 36.

- ↑ Herwig 2009, pp. 117, 112.

- ↑ FB 2008.

- ↑ Humphries & Maker 2013, p. 105.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1926, pp. 35, 41.

References

Books

- Buchan, J. (1921). A History of the Great War. Edinburgh: Nelson. OCLC 4083249.

- Cruttwell, C. R. M. F. (1982) [1934]. A History of the Great War 1914–1918 (2nd, Granada ed.). Oxford: OUP. ISBN 0-586-08398-7.

- Donnell, C. (2007). The Forts of the Meuse in World War I. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-114-4.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1926). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914: Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne August–October 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents, by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962523.

- Griffiths, William R. (2003). The Great War. The West Point military history series (repr. ed.). New York: Square One. ISBN 0-757-00158-0. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- Herwig, H. (2009). The Marne, 1914: The Opening of World War I and the Battle that Changed the World. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6671-1.

- Humphries, M. O.; Maker, J. (2013). Der Weltkrieg: 1914 The Battle of the Frontiers and Pursuit to the Marne. Germany's Western Front: Translations from the German Official History of the Great War. I. Part 1 (1st ed.). Waterloo, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-1-55458-373-7.

- Keegan, J. (2000). The First World War. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-37570-045-5.

- Skinner, H. T.; Stacke, H. Fitz M. (1922). Principal Events 1914–1918 (PDF). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. London: HMSO. OCLC 17673086. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- Strachan, H. (2001). The First World War: To Arms. I. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 0-19-926191-1.

- The war of 1914 Military Operations of Belgium in Defence of the Country and to Uphold Her Neutrality (PDF). London: W. H. & L Collingridge. 1915. OCLC 8651831. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- Tyng, S. (2007) [1935]. The Campaign of the Marne 1914 (Westholme Publishing, NY ed.). New York: Longmans, Green and Co. ISBN 1-59416-042-2.

- Zuber, T. (2010). The Mons Myth: A Reassessment of the Battle. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5247-0.

Websites

- "Liège". French Battlefields: Touring the Great Battlefields of Europe. Buffalo Grove, IL: French Battlefields. 2008. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- "Index des fortifications belges" [Index of Belgian Fortifications] (in French). Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- Vermeulen, J. (2000). "Belgian Fronts" [The Fortified Position of Liège]. Le Position Fortifiée de Liège. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

Further reading

Books

- Foley, R. T. (2007) [2005]. German Strategy and the Path to Verdun: Erich von Falkenhayn and the Development of Attrition, 1870–1916. Cambridge: CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-04436-3.

- Griess, T. E. (1986). The Great War. Wayne N J: Avery Publishing. ISBN 0-89529-303-X.

- Hamelius, P. (1914). The Siege of Liège: A Personal Narrative (PDF). London: T. W. Laurie. OCLC 609053696. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- Kennedy, J. M. (1914). The Campaign Around Liège (PDF). Daily Telegraph War Books. London. OCLC 494758224. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- Marshall, S. L. A. (1964). World War I. New York: American Heritage. ISBN 0-82810-434-4.

- Reynolds, F. J. (1916). The Story of the Great War: History of the European War from Official Sources, Complete Historical Records of Events to Date (PDF). III. New York: P. F. Collier & Son. OCLC 2678548. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

Websites

- Duffy, M. (2009). "The Battle of Liège, 1914". Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- Rickard, J. (2001). "Siege of Liège, 5–16 August 1914". Retrieved 4 January 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Liège. |

- German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial

- German Official History map of the advance to Liège OÖLB

- German and Belgian Order of Battle, Lüttich (Liège) 3–7 August 1914

- Hoet, J. C. Histoire des fortifications de Liège

- The Battle of Liège, 1914

- Siege of Liège, 5–15 August 1914

- The Fortresses of Liège

- Sambre–Marne–Yser (French)