Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC)

| Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Macedonian Conquest of Greece, and the Rise of Macedon | |||||||||

The Lion of Chaeronea, probably erected by the Thebans in memory of their dead. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Macedon | Athens, Thebes, Corinth, Megara, Achaea, Chalcis, Epidaurus, and Troezen | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Alexander |

Chares of Athens, Lysicles of Athens, Theagenes of Boeotia | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

30,000 infantry, 2,000 cavalry | 35,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| unknown | ~2,000 dead, ~4,000 captured | ||||||||

The Battle of Chaeronea was fought in 338 BC, near the city of Chaeronea in Boeotia, between the Macedonians led by Philip II of Macedon and an alliance of some of the Greek city-states including Athens and Thebes. The battle was the culmination of Philip's campaign in Greece (339–338 BC) and resulted in a decisive victory for the Macedonians.

Philip had brought peace to a war-torn Greece in 346 BC, by ending the Third Sacred War, and concluding his ten-year conflict with Athens for supremacy in the north Aegean, by making a separate peace. Philip's much expanded kingdom, powerful army and plentiful resources now made him the de facto leader of Greece. To many of the fiercely independent Greek city-states, Philip's power after 346 BC was perceived as a threat to their liberty, especially in Athens, where the politician Demosthenes led efforts to break away from Philip's influence. In 340 BC Demosthenes convinced the Athenian assembly to sanction action against Philip's territories and to ally with Byzantium, which Philip was besieging. These actions were against the terms of their treaty oaths and amounted to a declaration of war. In summer 339 BC, Philip therefore led his army towards South Greece, prompting the formation of an alliance of a few southern Greek states opposed to him, led by Athens and Thebes.

After several months of stalemate, Philip finally advanced into Boeotia in an attempt to march on Thebes and Athens. Opposing him, and blocking the road near Chaeronea, was the allied Greek army, similar in size and occupying a strong position. Details of the ensuing battle are scarce, but after a long fight the Macedonians crushed both flanks of the allied line, which then dissolved into a rout.

The battle has been described as one of the most decisive of the ancient world. The forces of Athens and Thebes were destroyed, and continued resistance was impossible; the war therefore came to an abrupt end. Philip was able to impose a settlement upon Greece, which all states accepted, with the exception of Sparta. The League of Corinth, formed as a result, made all participants allies of Macedon and each other, with Philip as the guarantor of the peace. In turn, Philip was voted as strategos (general) for a pan-Hellenic war against the Persian Empire, which he had long planned. However, before he was able to take charge of the campaign, Philip was assassinated, and the kingdom of Macedon and responsibility for the war with Persia passed instead to his son Alexander.

Background

In the decade following his accession in 359 BC, the Macedonian king, Philip II, had rapidly strengthened and expanded his kingdom into Thrace and Chalkidiki on the northern coast of the Aegean Sea.[1][2] He was aided in this process by the distraction of Athens and Thebes, the two most powerful city-states in Greece at that point, by events elsewhere. In particular, these events included the Social War between Athens and her erstwhile allies (357–355 BC), and the Third Sacred War which erupted in central Greece in 356 BC between the Phocians and the other members of the Delphic Amphictyonic League.[3][4] Much of Philip's expansion during this period was at the nominal expense of the Athenians, who considered the north Aegean coast as their sphere of influence, and Philip was at war with Athens from 356–346 BC.[2]

Philip was not originally a belligerent in the Sacred War, but became involved at the request of the Thessalians.[5][6] Seeing an opportunity to expand his influence into Greece proper, Philip obliged, and in 353 or 352 BC won a decisive victory over the Phocians at the Battle of Crocus Field in Thessaly.[7][8] In the aftermath, Philip was made archon of Thessaly,[9] which gave him control of the levies and revenues of the Thessalian Confederation, thereby greatly increasing his power.[10] However, Philip did not intervene further in the Sacred War until 346 BC. Early in that year, the Thebans, who had borne the brunt of the Sacred War, together with the Thessalians, asked Philip to assume the "leadership of Greece" and join them in fighting the Phocians.[11] Philip's power was by now so great that ultimately the Phocians did not even attempt to resist, and instead surrendered to him; Philip was thus able to end a particularly bloody war without any further fighting.[12] Philip allowed the Amphictyonic council the formal responsibility of punishing the Phocians, but ensured that the terms were not overly harsh; nevertheless, the Phocians were expelled from the Amphictyonic League, all their cities were destroyed, and they were resettled in villages of no more than fifty houses.[13]

By 346 BC, the Athenians were war-weary, unable to match Philip's strength, and had begun to contemplate the necessity of making peace.[14] Nevertheless, when it became apparent that Philip would march south that year, the Athenians originally planned to help the Phocians (whom they were allied to) keep Philip out of central Greece, by occupying the pass of Thermopylae, where Philip's superior numbers would be of little benefit.[15] The Athenians had successfully used this tactic to prevent Philip attacking Phocis itself after his victory at Crocus Field.[16] The occupation of Thermopylae was not only for the benefit of Phocis; excluding Philip from central Greece also prevented him from marching on Athens itself.[16] However, by the end of February, the general Phalaikos was restored to power in Phocis, and he refused to allow the Athenians access to Thermopylae.[17] Suddenly unable to guarantee their own security, the Athenians were forced instead into making peace with Philip; the treaty that was agreed (the Peace of Philocrates) also made Athens reluctant allies of Macedon.[18]

For the Athenians, the treaty had been expedient, but it was never popular. Philip's actions in 346 BC had expanded his influence over all Greece, and although he had brought peace, he had come to be seen as the enemy of the traditional liberty of the city-states. The orator and politician Demosthenes had been a principal architect of the Peace of Philocrates, but almost as soon as it was agreed, he wished to be rid of it.[19] Over the next few years, Demosthenes became leader of the "war-party" in Athens, and at every opportunity he sought to undermine the peace. From 343 BC onwards, in order to try to disrupt the peace, Demosthenes and his followers used every expedition and action of Philip to argue that he was breaking the peace.[20][21] Conversely, there was at first a substantial body of feeling in Athens, led by Aeschines, that the peace, unpopular though it was, should be maintained and developed.[22] Towards the end of the decade however, the "war party" gained the ascendancy, and began to openly goad Philip; in 341 BC for instance, the Athenian general Diopithes ravaged the territory of Philip's ally Cardia, even though Philip demanded that they desist.[23] Philip's patience finally ran out when the Athenians formed an alliance with Byzantium, which Philip was at that time besieging, and he wrote the Athenians declaring war.[24] Shortly afterward Philip broke off the siege of Byzantium; Cawkwell suggests that Philip had decided to deal with Athens once and for all.[25] Philip went on campaign against the Scythians, and then began to prepare for war in Greece.[26]

Prelude

Philip's forthcoming campaign in Greece became linked with a new, fourth, Sacred War. The citizens of Amphissa in Ozolian Locris had begun cultivating land sacred to Apollo on the Crisaean Plain south of Delphi; after some internal bickering the Amphictyonic council decided to declare a sacred war against Amphissa.[27] A Thessalian delegate proposed that Philip should be made leader of the Amphictyonic effort, which therefore gave Philip a pretext to campaign in Greece; it is, however, probable that Philip would have gone ahead with his campaign anyway.[27]

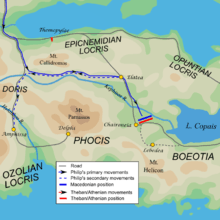

At the start of 339 BC, the Thebans had seized the town of Nicaea near Thermopylae, which Philip had garrisoned in 346 BC.[27] Philip does not appear to have treated this as a declaration of war, but it nevertheless presented him with a significant problem, blocking the main route into Greece.[27] However, a second route into central Greece was available, leading over the shoulder of Mount Callidromos and descending into Phocis.[27] However, the Athenians and Thebans had either forgotten the existence of this road, or believed that Philip would not use it; the subsequent failure to guard this road allowed Philip to slip into central Greece unhindered.[28] Philip's relatively lenient treatment of the Phocians at the end of the Third Sacred War in 346 BC now bore fruit. Reaching Elatea, he ordered the city to be re-populated, and during the next few months the whole Phocian Confederation was restored to its former state.[28] This provided Philip with a base in Greece, and new, grateful allies in the Phocians.[28] Philip probably arrived in Phocis in November 339 BC, but the Battle of Chaeronea did not occur until August 338 BC.[28] During this period Philip discharged his responsibility to the Amphicytonic council by settling the situation in Amphissa. He tricked a force of 10,000 mercenaries who were guarding the road from Phocis to Amphissa into abandoning their posts, then took Amphissa and expelled its citizens, turning it over to Delphi.[29] He probably also engaged in diplomatic attempts to avoid further conflict in Greece, although if so, he was unsuccessful.[28]

When news first arrived that Philip was in Elatea, just three days march away, there was panic in Athens.[30] In what Cawkwell describes as his proudest moment, Demosthenes alone counseled against despair, and proposed that the Athenians should seek an alliance with the Thebans; his decree was passed, and he was sent as ambassador.[30] Philip had also sent an embassy to Thebes, requesting that the Thebans join him, or at least allow him to pass through Boeotia unhindered.[29] Since the Thebans were still not formally at war with Philip, they could have avoided the conflict altogether.[30] However, in spite of Philip's proximity, and their traditional enmity with Athens, they chose to ally with the Athenians, in the cause of liberty for Greece.[29] The Athenian army had already pre-emptively been sent in the direction of Boeotia, and was therefore able to join the Thebans within days of the alliance being agreed.[30]

The details of the campaign leading up to Chaeronea are almost completely unknown.[31] Philip was presumably prevented from entering Boeotia by way of Mount Helicon, as the Spartans had done in the run-up to the Battle of Leuctra; or by any of the other mountain passes that led into Boeotia from Phocis.[31] There were certainly some preliminary skirmishes; Demosthenes alludes to a "winter battle" and "battle on the river" in his speeches, but no other details are preserved.[31] Finally, in August 338 BC, Philip's army marched straight down the main road from Phocis to Boeotia, to assault the main allied army defending the road at Chaeronea.[31]

Opposing forces

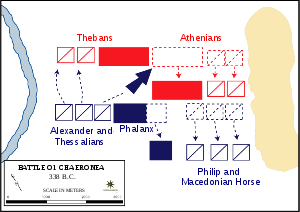

According to Diodorus, the Macedonian army numbered roughly 30,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry, a figure generally accepted by modern historians.[31][32] Philip took command of the right wing of the Macedonian army and placed his 18-year-old son Alexander (the future conqueror of the Persian Empire) in command of the left wing, accompanied by a group of Philip's experienced generals.[32]

The allied Greek army included contingents from Achaea, Corinth, Chalcis, Epidaurus, Megara and Troezen, with the majority of troops being supplied by Athens and Thebes. The Athenian contingent was led by the generals Chares and Lysicles, and the Thebans by Theagenes. No source provides exact numbers for the Greek army, although Justin suggests that the Greeks were "far superior in number of soldiers";[33] the modern view is that the numbers of the city states that fought were approximately equal to those of the Macedonians.[31] The Athenians took up positions on the left wing, the Thebans on the right, and the other allies in the centre.[34]

Strategic and tactical considerations

The Greek army had taken up a position near Chaeronea, astride the main road.[34] On the left flank, the Greek line lay across the foothills of Mount Thurion, blocking the side-road that led to Lebedea, while on the right, the line rested against the Kephisos River, near a projecting spur of Mount Aktion.[34] The Greek line, which was about 2.5 miles in length, was thus secure on both flanks. Moreover, the Greek line seems to have slanted north-eastwards across the plain in between, so that it did not face the direction of Macedonian advance full-square.[34] This prevented Philip from attempting to concentrate his force on the Greek right wing, since the advanced position of the Greek left wing would then threaten Philip's right. Although Philip could attempt to concentrate his force against the Greek left, the troops there occupied high ground, and any attack would be difficult.[34] Since the Greeks could remain on the defensive, having only to prevent Philip's advance, their position was therefore strategically and tactically very strong.[34]

Battle

Details of the battle itself are scarce, with Diodorus providing the only formal account. He says that "once joined, the battle was hotly contested for a long time and many fell on both sides, so that for a while the struggle permitted hopes of victory to both."[35] He then recounts that the young Alexander, "his heart set on showing his father his prowess" succeeded in rupturing the Greek line aided by his companions, and eventually put the Greek right wing to flight; meanwhile, Philip advanced in person against the Greek left and also put it to flight.[35]

This brief account can be filled out, if Polyaenus's account of the battle is to be believed. Polyaenus collected many snippets of information on warfare in his Strategems; some are known from other sources to be reliable, while others are demonstrably false.[36] In the absence of other evidence, it is unclear whether his passage regarding Chaeronea is to be accepted or rejected.[36] Polyaenus suggests that Philip engaged the Greek left, but then withdrew his troops; the Athenians on the Greek left followed and, when Philip held the high ground, he stopped retreating and attacked the Athenians, eventually routing them.[36][37] In another 'stratagem', Polyaenus suggests that Philip deliberately prolonged the battle, to take advantage of the rawness of the Athenian troops (his own veterans being more used to fatigue) and delayed his main attack until the Athenians were exhausted.[38] This latter anecdote also appears in the earlier Stratagems of Frontinus.[39]

Polyaenus's accounts have led some modern historians to tentatively propose the following synthesis of the battle. After the general engagement had been in progress for some time, Philip had his army perform a wheeling manoeuver, with the right wing withdrawing, and the whole line pivoting around its centre.[40] At the same time, wheeling forward, the Macedonian left wing attacked the Thebans on the Greek right and punched a hole in the Greek line.[40] On the Greek left, the Athenians followed Philip, their line becoming stretched and disordered;[40] the Macedonians then turned, attacked and routed the tired and inexperienced Athenians. The Greek right wing, under the assault of the Macedonian troops under Alexander's command, then also routed, ending the battle.[40]

Many historians, including Hammond and Cawkwell, place Alexander in charge of the Companion Cavalry during the battle, perhaps because of Diodorus's use of the word "companions".[41] However, there is no mention of cavalry in any ancient account of the battle, nor does there seem to have been space for it to operate against the flank of the Greek army.[41] Plutarch says that Alexander was the "first to break the ranks of the Sacred Band of the Thebans", the elite of the Theban infantry, who were stationed on the extreme right of the Greek battle line.[42] However, he also says that the Sacred Band had "met the spears of [the Macedonian] phalanx face to face".[43] This, together with the improbability that a head-on cavalry charge against the spear-armed Thebans could have succeeded (because horses will generally shy from such a barrier), has led Gaebel and others to suggest that Alexander must have been commanding a portion of the Macedonian phalanx at Chaeronea.[41]

Diodorus says that more than 1,000 Athenians died in the battle, with another 2,000 taken prisoner, and that the Thebans fared similarly.[35] Plutarch suggests that all 300 of the Sacred Band were killed at the battle, having previously been seen as invincible.[43] In the Roman period, the 'Lion of Chaeronea', an enigmatic monument on the site of the battle, was believed to mark the resting place of the Sacred Band.[44] Modern excavations found the remains of 254 soldiers underneath the monument; it is therefore generally accepted that this was indeed the grave of the Sacred Band, since it is unlikely that every member was killed.[40]

Aftermath

Cawkwell suggests that this was one of the most decisive battles in ancient history.[40] Since there was now no army which could prevent Philip's advance, the war effectively ended.[40] In Athens and Corinth, records show desperate attempts to re-build the city walls, as they prepared for siege.[45] However, Philip had no intention of besieging any city, nor indeed of conquering Greece. He wanted the Greeks as his allies for his planned campaign against the Persians, and he wanted to leave a stable Greece in his rear when he went on campaign; further fighting was therefore contrary to his aims.[45] Philip marched first to Thebes, which surrendered to him; he expelled the Theban leaders who had opposed him, recalled those pro-Macedonian Thebans who had previously been exiled, and installed a Macedonian garrison.[46] He also ordered that the Boeotian cities of Plataea and Thespiae, which Thebes had destroyed in previous conflicts, be re-founded. Generally, Philip treated the Thebans severely, making them pay for the return of their prisoners, and even to bury their dead; he did not, however, dissolve the Boeotian Confederacy.[46]

By contrast, Philip treated Athens very leniently; although the Second Athenian Confederacy was dissolved, the Athenians were allowed to keep their colony on Samos, and their prisoners were freed without ransom.[47] Philip's motives are not entirely clear, but one likely explanation is that he hoped to use the Athenian navy in his campaign against Persia, since Macedon did not possess a substantial fleet; he therefore needed to remain on good terms with the Athenians.[47] Philip also made peace with the other combatants; Corinth and Chalcis, which controlled important strategic locations both received Macedonian garrisons.[48] He then turned to deal with Sparta, which had not taken part in the conflict, but was likely to take advantage of the weakened state of the other Greek cities to try to attack its neighbours in the Peloponnese.[49] The Spartans refused Philip's invitation to engage in discussions, so Philip ravaged Lacedaemonia, but did not attack Sparta itself.[49]

Philip seems to have moved around Greece in the months after the battle, making peace with the states that opposed him, dealing with the Spartans, and installing garrisons; his movements also probably served as a demonstration of force to the other cities, that they should not try to oppose him.[47] In mid 337 BC, he seems to have camped near Corinth, and began the work to establish a league of the Greek city-states, which would guarantee peace in Greece, and provide Philip with military assistance against Persia.[47] The result, the League of Corinth, was formed in the latter half of 337 BC at a congress organised by Philip. All states signed up to the league, with the exception of Sparta.[50] The principal terms of the concord were that all members became allied to each other, and to Macedon, and that all members were guaranteed freedom from attack, freedom of navigation, and freedom from interference in internal affairs.[51] Philip, and the Macedonian garrisons installed in Greece, would act as the 'keepers of the peace'.[51] At Philip's behest, the synod of the league then declared war on Persia, and voted Philip as Strategos for the forthcoming campaign.[50]

An advance Macedonian force was sent to Persia in early 336 BC, with Philip due to follow later in the year.[50] However, before he could depart, Philip was assassinated by one of his bodyguards.[52] Alexander therefore became King of Macedon, and in a series of campaigns lasting from 334 to 323 BC, he conquered the whole Persian Empire.

Thematic appraisal

- Philip's feint withdrawal was the main tactic which stemmed all the subsequent planned manoeuvres.

- It lured on the Athenian left wing to the front and left, which thereby extended and weakened the whole line.

- This meant that a gap created somewhere along the line, probably between the center and the Theban Sacred Band on the right.

- It was through this gap Alexander and the cavalry charged. He thus made the first break in the line.

- Alexander had surrounded the Sacred Band, who refused to move and were thus annihilated.

- Philip on the other hand counter-attacked the Athenian left wing and routed it.

- The rest of the Athenian line was next rolled up from both ends.[53]

References

Citations

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, pp. 29–49.

- 1 2 Cawkwell 1978, pp. 69–90.

- ↑ Buckley 1996, p. 470.

- ↑ Hornblower 2002, p. 272.

- ↑ Buckler 1989, p. 63.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, p. 61.

- ↑ Buckler 1989, pp. 64–74.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, pp. 60–66.

- ↑ Buckler 1989, p. 78.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, p. 62.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, p. 102.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, p. 106.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, p. 107.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, p. 91.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, p. 95.

- 1 2 Buckler 1989, p. 81.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, p. 96.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, pp. 96–101.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, p. 118.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, p. 119.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, p. 133.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, p. 120.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, p. 131.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, p. 137.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, pp. 139–140.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, p. 140.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cawkwell 1978, p. 141.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cawkwell 1978, p. 142.

- 1 2 3 Cawkwell 1978, p. 144.

- 1 2 3 4 Cawkwell 1978, p. 143.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cawkwell 1978, p. 145.

- 1 2 Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca Historica, 16.85.

- ↑ Justin. Epitome of Pompeius Trogus's Philippic History, 9.3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cawkwell 1978, pp. 146–147.

- 1 2 3 Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca Historica, 16.86.

- 1 2 3 Cawkwell 1978, p. 147.

- ↑ Polyaenus. Stratagems in War, 4.2.2.

- ↑ Polyaenus. Stratagems in War, 4.2.7.

- ↑ Sextus Julius Frontinus. Stratagems, 2.1.9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cawkwell 1978, p. 148.

- 1 2 3 Gaebel 2004, pp. 155–156.

- ↑ Plutarch. Parallel Lives, "Alexander", 9.

- 1 2 Plutarch. Parallel Lives, "Pelopidas", 18.

- ↑ Pausanias. Description of Greece, 9.40.10.

- 1 2 Cawkwell 1978, p. 166.

- 1 2 Cawkwell 1978, pp. 167–168.

- 1 2 3 4 Cawkwell 1978, p. 167.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, p. 168.

- 1 2 Cawkwell 1978, p. 169.

- 1 2 3 Cawkwell 1978, p. 170.

- 1 2 Cawkwell 1978, p. 171.

- ↑ Cawkwell 1978, p. 179.

- ↑ Montagu, John Drogo (2006). Greek & Roman Warfare: Battles, Tactics, and Trickery. London: Greenhill Books. p. 148.

Sources

- Buckler, John (1989). Philip II and the Sacred War. Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-09095-9.

- Buckley, Terry (1996). Aspects of Greek History, 750-323 BC: A Source-based Approach. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-09957-9.

- Cawkwell, George (1978). Philip II of Macedon. London, United Kingdom: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-10958-6.

- Davis, Paul K. (1999). 100 Decisive Battles from Ancient Times to the Present: The World’s Major Battles and How They Shaped History. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514366-3.

- Gaebel, Robert E. (2004). Cavalry Operations in the Ancient Greek World. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3444-5.

- Hornblower, Simon (2002). The Greek World, 479-323 BC (Third ed.). London, United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16326-9.

External links