Battle of Cape Esperance

| Battle of Cape Esperance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific Theater of World War II | |||||||

The heavily damaged Japanese cruiser Aoba disembarks dead and wounded crew members near Buin, Bougainville and the Shortland Islands a few hours after the battle on October 12, 1942 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

4 cruisers 5 destroyers |

3 cruisers 2 destroyers, reinforcement convoy (indirectly involved): 6 destroyers, 2 seaplane tenders | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1 destroyer sunk 1 cruiser damaged 1 destroyer damaged 163 killed[1] |

1 cruiser sunk 1 destroyer sunk 1 cruiser damaged 341–454 killed 111 captured[2] | ||||||

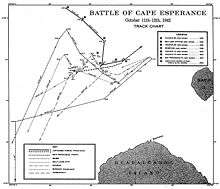

The Battle of Cape Esperance, also known as the Second Battle of Savo Island and, in Japanese sources, as the Sea Battle of Savo Island (サボ島沖海戦), took place on 11–12 October 1942 in the Pacific campaign of World War II between the Imperial Japanese Navy and United States Navy. The naval battle was the second of four major surface engagements during the Guadalcanal campaign and took place at the entrance to the strait between Savo Island and Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. Cape Esperance (9°15′S 159°42′E / 9.250°S 159.700°E) is the northernmost point on Guadalcanal, and the battle took its name from this point.

On the night of 11 October, Japanese naval forces in the Solomon Islands area—under the command of Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa—sent a major supply and reinforcement convoy to their forces on Guadalcanal. The convoy consisted of two seaplane tenders and six destroyers and was commanded by Rear Admiral Takatsugu Jojima. At the same time, but in a separate operation, three heavy cruisers and two destroyers—under the command of Rear Admiral Aritomo Gotō—were to bombard the Allied airfield on Guadalcanal (called Henderson Field by the Allies) with the object of destroying Allied aircraft and the airfield's facilities.

Shortly before midnight on 11 October, a U.S force of four cruisers and five destroyers—under the command of Rear Admiral Norman Scott—intercepted Gotō's force as it approached Savo Island near Guadalcanal. Taking the Japanese by surprise, Scott's warships sank one of Gotō's cruisers and one of his destroyers, heavily damaged another cruiser, mortally wounded Gotō, and forced the rest of Gotō's warships to abandon the bombardment mission and retreat. During the exchange of gunfire, one of Scott's destroyers was sunk and one cruiser and another destroyer were heavily damaged. In the meantime, the Japanese supply convoy successfully completed unloading at Guadalcanal and began its return journey without being discovered by Scott's force. Later on the morning of 12 October, four Japanese destroyers from the supply convoy turned back to assist Gotō's retreating, damaged warships. Air attacks by U.S. aircraft from Henderson Field sank two of these destroyers later that day.

As with the preceding naval engagements around Guadalcanal, the strategic outcome was inconclusive because neither the Japanese nor United States navies secured operational control of the waters around Guadalcanal as a result of this action. However, the Battle of Cape Esperance provided a significant morale boost to the US Navy after the disaster of Savo Island.

Background

On 7 August 1942, Allied forces (primarily U.S.) landed on Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and Florida Islands in the Solomon Islands. The objective was to deny the islands to the Japanese as bases for threatening the supply routes between the U.S. and Australia, and secure starting points for a campaign to isolate the major Japanese base at Rabaul while also supporting the Allied New Guinea campaign. The Guadalcanal campaign would last six months.[3]

Taking the Japanese by surprise, by nightfall on 8 August, the Allied forces, mainly consisting of U.S. Marines, had secured Tulagi and nearby small islands, as well as an airfield under construction at Lunga Point on Guadalcanal (later completed and named Henderson Field). Allied aircraft operating out of Henderson became known as the "Cactus Air Force" (CAF) after the Allied codename for Guadalcanal.[4]

In response, the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters assigned the Imperial Japanese Army's 17th Army—a corps-sized formation headquartered at Rabaul under Lieutenant-General Harukichi Hyakutake—with the task of retaking Guadalcanal. On 19 August, various units of the 17th Army began to arrive on the island.[5]

Due to the threat of Allied aircraft, the Japanese were unable to use large, slow transport ships to deliver their troops and supplies to the island, and warships were used instead. These ships—mainly light cruisers or destroyers—were usually able to make the round trip down "The Slot" to Guadalcanal and back in a single night, thereby minimizing their exposure to air attacks. Delivering troops in this manner, however, prevented most of the heavy equipment and supplies, such as heavy artillery, vehicles, and much food and ammunition, from being delivered. In addition, they expended destroyers that were desperately needed for commerce defense. These high-speed runs occurred throughout the campaign and were later called the "Tokyo Express" by the Allies and "Rat Transportation" by the Japanese.[6]

Due to the heavier concentration of Japanese surface combat vessels and their well positioned logistical base at Simpson Harbor, Rabaul, and their victory at the Battle of Savo Island in early August, the Japanese had established operational control over the waters around Guadalcanal at night. However, any Japanese ship remaining within range of American aircraft at Henderson field, during the daylight hours—about 200 mi (170 nmi; 320 km)—was in danger of damaging air attack. This persisted for the months of August and September 1942. The presence of Admiral Scott's task force at Cape Esperance represented the US Navy's first major attempt to wrest night time operational control of waters around Guadalcanal away from the Japanese.[7]

The first attempt by the Japanese Army to recapture Henderson Field was on 21 August, in the Battle of the Tenaru, and the next, the Battle of Edson's Ridge, from 12–14 September; both failed.[8]

The Japanese set their next major attempt to recapture Henderson Field for 20 October and moved most of the 2nd and 38th Infantry Divisions, totalling 17,500 troops, from the Dutch East Indies to Rabaul in preparation for delivering them to Guadalcanal. From 14 September-9 October, numerous Tokyo Express runs delivered troops from the Japanese 2nd Infantry Division as well as General Hyakutake to Guadalcanal. In addition to cruisers and destroyers, some of these runs included the seaplane carrier Nisshin, which delivered heavy equipment to the island including vehicles and heavy artillery other warships could not carry because of space limitations. The Japanese Navy promised to support the Army's planned offensive by delivering the necessary troops, equipment, and supplies to the island, and by stepping up air attacks on Henderson Field and sending warships to bombard the airfield.[9]

In the meantime, Major General Millard F. Harmon—commander of United States Army forces in the South Pacific—convinced Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley—overall commander of Allied forces in the South Pacific—that the Marines on Guadalcanal needed to be reinforced immediately if the Allies were to successfully defend the island from the next expected Japanese offensive. Thus, on 8 October, the 2,837 men of the 164th Infantry Regiment from the U.S. Army's Americal Division boarded ships at New Caledonia for the trip to Guadalcanal with a projected arrival date of 13 October.[10]

To protect the transports carrying the 164th to Guadalcanal, Ghormley ordered Task Force 64 (TF 64), consisting of four cruisers (San Francisco, Boise, Salt Lake City, and Helena) and five destroyers (Farenholt, Duncan, Buchanan, McCalla, and Laffey) under U.S. Rear Admiral Norman Scott, to intercept and combat any Japanese ships approaching Guadalcanal and threatening the convoy. Scott conducted one night battle practice with his ships on 8 October, then took station south of Guadalcanal near Rennell Island on 9 October, to await word of any Japanese naval movement toward the southern Solomons.[11]

Continuing with preparations for the October offensive, Japanese Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa's Eighth Fleet staff, headquartered at Rabaul, scheduled a large and important Tokyo Express supply run for the night of 11 October. Nisshin would be joined by the seaplane carrier Chitose to deliver 728 soldiers, four large howitzers, two field guns, one anti-aircraft gun, and a large assortment of ammunition and other equipment from the Japanese naval bases in the Shortland Islands and at Buin, Bougainville, to Guadalcanal. Six destroyers, five of them carrying troops, would accompany Nisshin and Chitose. The supply convoy—called the "Reinforcement Group" by the Japanese—was under the command of Rear Admiral Takatsugu Jojima. At the same time but in a separate operation, the three heavy cruisers of Cruiser Division 6 (CruDiv6)—Aoba, Kinugasa, and Furutaka, under the command of Rear Admiral Aritomo Gotō—were to bombard Henderson Field with special explosive shells with the object of destroying the CAF and the airfield's facilities. Two screening destroyers—Fubuki and Hatsuyuki—accompanied CruDiv6. Since U.S. Navy warships had yet to attempt to interdict any Tokyo Express missions to Guadalcanal, the Japanese were not expecting any opposition from U.S. naval surface forces that night.[12]

Battle

Prelude

At 08:00 on 11 October, Jojima's reinforcement group departed the Shortland Islands anchorage to begin their 250 mi (220 nmi; 400 km) run down the Slot to Guadalcanal. The six destroyers that accompanied Nisshin and Chitose were Asagumo, Natsugumo, Yamagumo, Shirayuki, Murakumo, and Akizuki. Gotō departed the Shortland Islands for Guadalcanal at 14:00 the same day.[13]

To protect the reinforcement group's approach to Guadalcanal from the CAF, the Japanese 11th Air Fleet, based at Rabaul, Kavieng, and Buin, planned two air strikes on Henderson Field for 11 October. A "fighter sweep" of 17 Mitsubishi A6M3 Zero fighters swept over Henderson Field just after mid-day but failed to engage any U.S. aircraft. Forty-five minutes later, the second wave—45 Mitsubishi G4M2 "Betty" bombers and 30 Zeros—arrived over Henderson Field. In an ensuing air battle with the CAF, one G4M and two U.S. fighters were downed. Although the Japanese attacks failed to inflict significant damage, they did prevent CAF bombers from finding and attacking the reinforcement group. As the reinforcement group transited the Slot, relays of 11th Air Fleet Zeros from Buin provided escort. Emphasizing the importance of this convoy for Japanese plans, the last flight of the day was ordered to remain on station over the convoy until darkness, then ditch their aircraft and await pickup by the reinforcement group's destroyers. All six Zeros ditched; only one pilot was recovered.[14]

Allied reconnaissance aircraft sighted Jojima's supply convoy 210 mi (180 nmi; 340 km) from Guadalcanal between Kolombangara and Choiseul in the Slot at 14:45 on the same day, and reported it as two "cruisers" and six destroyers. Gotō's force—following the convoy—was not sighted. In response to the sighting of Jojima's force, at 16:07 Scott turned toward Guadalcanal for an interception.[15]

Scott crafted a simple battle plan for the expected engagement. His ships would steam in column with his destroyers at the front and rear of his cruiser column, searching across a 300 degree arc with SG surface radar in an effort to gain positional advantage on the approaching enemy force. The destroyers were to illuminate any targets with searchlights and discharge torpedoes while the cruisers were to open fire at any available targets without awaiting orders. The cruiser's float aircraft, launched in advance, were to find and illuminate the Japanese warships with flares. Although Helena and Boise carried the new, greatly improved SG radar, Scott chose San Francisco as his flagship.[16]

At 22:00, as Scott's ships neared Cape Hunter at the northwest end of Guadalcanal, three of Scott's cruisers launched floatplanes. One crashed on takeoff, but the other two patrolled over Savo Island, Guadalcanal, and Ironbottom Sound. As the floatplanes were launched, Jojima's force was just passing around the mountainous northwestern shoulder of Guadalcanal, and neither force sighted each other. At 22:20, Jojima radioed Gotō and told him that no U.S. ships were in the vicinity. Although Jojima's force later heard Scott's floatplanes overhead while unloading along the north shore of Guadalcanal, they failed to report this to Gotō.[17]

At 22:33, just after passing Cape Esperance, Scott's ships assumed battle formation. The column was led by Farenholt, Duncan, and Laffey, and followed by San Francisco, Boise, Salt Lake City, and Helena. Buchanan and McCalla brought up the rear. The distance between each ship ranged from 500 to 700 yd (460 to 640 m). Visibility was poor because the moon had already set, leaving no ambient light and no visible sea horizon.[18]

Gotō's force passed through several rain squalls as they approached Guadalcanal at 30 kn (35 mph; 56 km/h). Gotō's flagship Aoba led the Japanese cruisers in column, followed by Furutaka and Kinugasa. Fubuki was starboard of Aoba and Hatsuyuki to port. At 23:30, Gotō's ships emerged from the last rain squall and began appearing on the radar scopes of Helena and Salt Lake City. The Japanese, however, whose warships were not equipped with radar, remained unaware of Scott's presence.[19]

Action

At 23:00, the San Francisco aircraft spotted Jojima's force off Guadalcanal and reported it to Scott. Scott, believing that more Japanese ships were likely still on the way, continued his course towards the west side of Savo Island. At 23:33, Scott ordered his column to turn towards the southwest to a heading of 230°. All of Scott's ships understood the order as a column movement except Scott's own ship, San Francisco. As the three lead U.S. destroyers executed the column movement, San Francisco turned simultaneously. Boise—following immediately behind—followed San Francisco, thereby throwing the three van destroyers out of formation.[20]

At 23:32, Helena's radar showed the Japanese warships to be about 27,700 yd (25,300 m) away. At 23:35, Boise's and Duncan's radars also detected Gotō's ships. Between 23:42 and 23:44, Helena and Boise reported their contacts to Scott on San Francisco who mistakenly believed that the two cruisers were actually tracking the three U.S. destroyers that were thrown out of formation during the column turn. Scott radioed Farenholt to ask if the destroyer was attempting to resume its station at the front of the column. Farenholt replied, "Affirmative, coming up on your starboard side," further confirming Scott's belief that the radar contacts were his own destroyers.[21]

At 23:45, Farenholt and Laffey—still unaware of Gotō's approaching warships—increased speed to resume their stations at the front of the U.S. column. Duncan's crew, however, thinking that Farenholt and Laffey were commencing an attack on the Japanese warships, increased speed to launch a solitary torpedo attack on Gotō's force without telling Scott what they were doing. San Francisco's radar registered the Japanese ships, but Scott was not informed of the sighting. By 23:45, Gotō's ships were only 5,000 yd (4,600 m) away from Scott's formation and visible to Helena's and Salt Lake City's lookouts. The U.S. formation at this point was in position to cross the T of the Japanese formation, giving Scott's ships a significant tactical advantage. At 23:46, still assuming that Scott was aware of the rapidly approaching Japanese warships, Helena radioed for permission to open fire, using the general procedure request, "Interrogatory Roger" (meaning, basically, "Are we clear to act?"). Scott answered with, "Roger", only meaning that the message was received, not that he was confirming the request to act. Upon receipt of Scott's "Roger", Helena—thinking they now had permission—opened fire, quickly followed by Boise, Salt Lake City, and to Scott's further surprise, San Francisco.[22]

Gotō's force was taken almost completely by surprise. At 23:43, Aoba's lookouts sighted Scott's force, but Gotō assumed that they were Jojima's ships. Two minutes later, Aoba's lookouts identified the ships as American, but Gotō remained skeptical and directed his ships to flash identification signals. As Aoba's crew executed Gotō's order, the first American salvo smashed into Aoba's superstructure. Aoba was quickly hit by up to 40 shells from Helena, Salt Lake City, San Francisco, Farenholt, and Laffey. The shell hits heavily damaged Aoba's communications systems and demolished two of her main gun turrets as well as her main gun director. Several large-caliber projectiles passed through Aoba's flag bridge without exploding, but the force of their passage killed many men and mortally wounded Gotō.[23]

Scott—still unsure who his ships were firing at, and afraid that they might be firing on his own destroyers—ordered a ceasefire at 23:47, although not every ship complied. Scott ordered Farenholt to flash her recognition signals and upon observing that Farenholt was close to his formation, he ordered the fire resumed at 23:51.[24]

Aoba, continuing to receive damaging hits, turned to starboard to head away from Scott's formation and began making a smoke screen which led most of the Americans to believe that she was sinking. Scott's ships shifted their fire to Furutaka, which was following behind Aoba. At 23:49, Furutaka was hit in her torpedo tubes, igniting a large fire that attracted even more shellfire from the US ships. At 23:58, a torpedo from Buchanan hit Furutaka in her forward engine room, causing severe damage. During this time, San Francisco and Boise sighted Fubuki about 1,400 yd (1,300 m) away and raked her with shellfire, joined soon by most of the rest of Scott's formation. Heavily damaged, Fubuki began to sink. Kinugasa and Hatsuyuki chose turning to port rather than starboard and escaped the Americans' immediate attention.[25]

During the exchange of gunfire, Farenholt received several damaging hits from both the Japanese and American ships, killing several men. She escaped from the crossfire by crossing ahead of San Francisco and passing to the disengaged side of Scott's column. Duncan—still engaged in her solitary torpedo attack on the Japanese formation—was also hit by gunfire from both sides, set afire, and looped away in her own effort to escape the crossfire.[26]

As Gotō's ships endeavored to escape, Scott's ships tightened their formation and then turned to pursue the retreating Japanese warships. At 00:06, two torpedoes from Kinugasa barely missed Boise. Boise and Salt Lake City turned on their searchlights to help target the Japanese ships, giving Kinugasa's gunners clear targets. At 00:10, two shells from Kinugasa exploded in Boise's main ammunition magazine between turrets one and two. The resulting explosion killed almost 100 men and threatened to blow the ship apart. Seawater rushed in through rents in her hull opened by the explosion and helped quench the fire before it could explode the ship's powder magazines. Boise immediately sheered out of the column and retreated from the action. Kinugasa and Salt Lake City exchanged fire with each other, each hitting the other several times, causing minor damage to Kinugasa and damaging one of Salt Lake City's boilers, reducing her speed.[27]

At 00:16, Scott ordered his ships to turn to a heading of 330° in an attempt to pursue the fleeing Japanese ships. Scott's ships, however, quickly lost sight of Gotō's ships, and all firing ceased by 00:20. The American formation was beginning to scatter, so Scott ordered a turn to 205° to disengage.[28]

Retreat

During the battle between Scott's and Gotō's ships, Jojima's reinforcement group completed unloading at Guadalcanal and began its return journey unseen by Scott's warships, using a route that passed south of the Russell Islands and New Georgia. Despite extensive damage, Aoba was able to join Kinugasa in retirement to the north through the Slot. Furutaka's damage caused her to lose power around 00:50, and she sank at 02:28, 22 mi (19 nmi; 35 km) northwest of Savo Island. Hatsuyuki picked up Furutaka's survivors and joined the retreat northward.[29]

Boise extinguished her fires by 02:40 and at 03:05 rejoined Scott's formation. Duncan—on fire—was abandoned by her crew at 02:00. Unaware of Duncan's fate, Scott detached McCalla to search for her and retired with the rest of his ships towards Nouméa, arriving in the afternoon of 13 October. McCalla located the burning, abandoned Duncan about 03:00, and several members of McCalla's crew made an attempt to keep her from sinking. By 12:00, however, they had to abandon the effort as bulkheads within Duncan collapsed causing the ship to finally sink 6 mi (5.2 nmi; 9.7 km) north of Savo Island. American servicemen in boats from Guadalcanal as well as McCalla picked up Duncan's scattered survivors from the sea around Savo. In total, 195 Duncan sailors survived; 48 did not. As they rescued Duncan's crew, the Americans came across the more than 100 Fubuki survivors, floating in the same general area. The Japanese initially refused all rescue attempts but a day later allowed themselves to be picked up and taken prisoner.[30]

Jojima—learning of the bombardment force's crisis—detached destroyers Shirayuki and Murakumo to assist Furutaka or her survivors and Asagumo and Natsugumo to rendezvous with Kinugasa, which had paused in her retreat northward to cover the withdrawal of Jojima's ships. At 07:00, five CAF Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless dive bombers attacked Kinugasa but inflicted no damage. At 08:20, 11 more SBDs found and attacked Shirayuki and Murakumo. Although they scored no direct hits, a near miss caused Murakumo to begin leaking oil, marking a trail for other CAF aircraft to follow. A short time later, seven more CAF SBDs plus six Grumman TBF-1 Avenger torpedo bombers, accompanied by 14 Grumman F4F-4 Wildcats, found the two Japanese destroyers 170 mi (150 nmi; 270 km) from Guadalcanal. In the ensuing attack, Murakumo was hit by a torpedo in her engineering spaces, leaving her without power. In the meantime, Aoba and Hatsuyuki reached the sanctuary of the Japanese base in the Shortland Islands at 10:00.[31]

Rushing to assist Murakumo, Asagumo and Natsugumo were attacked by another group of 11 CAF SBDs and TBFs escorted by 12 fighters at 15:45. An SBD placed its bomb almost directly amidships on Natsugumo while two more near misses contributed to her severe damage. After Asagumo took off her survivors, Natsugumo sank at 16:27. The CAF aircraft also scored several more hits on the stationary Murakumo, setting her afire. After her crew abandoned ship, Shirayuki scuttled her with a torpedo, picked up her survivors, and joined the rest of the Japanese warships for the remainder of their return trip to the Shortland Islands.[32]

Aftermath and significance

Captain Kikunori Kijima—Gotō's chief of staff and commander of the bombardment force during the return trip to the Shortland Islands after Gotō's death in battle—claimed that his force had sunk two American cruisers and one destroyer. Furutaka's captain—who survived the sinking of his ship—blamed the loss of his cruiser on bad air reconnaissance and poor leadership from the 8th fleet staff under Admiral Mikawa. Although Gotō's bombardment mission failed, Jojima's reinforcement convoy was successful in delivering the crucial men and equipment to Guadalcanal. Aoba journeyed to Kure, Japan, for repairs that were completed on February 15, 1943. Kinugasa was sunk one month later during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal.[33]

Scott claimed that his force sank three Japanese cruisers and four destroyers. News of the victory was widely publicized in the American media. Boise—which was damaged enough to require a trip to the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard for repairs—was dubbed the "one-ship fleet" by the press for her exploits in the battle, although this was mainly because the names of the other involved ships were withheld for security reasons. Boise was under repair until 20 March 1943.[34]

Although a tactical victory for the U.S., Cape Esperance had little immediate strategic effect on the situation on Guadalcanal. Just two days later on the night of 13 October, the Japanese battleships Kongō and Haruna bombarded and almost destroyed Henderson Field. One day after that, a large Japanese convoy successfully delivered 4,500 troops and equipment to the island. These troops and equipment helped complete Japanese preparations for the large land offensive scheduled to begin on 23 October. The convoy of U.S. Army troops reached Guadalcanal on 13 October as planned and were key participants for the Allied side in the decisive land battle for Henderson Field that took place from 23–26 October.[35]

The Cape Esperance victory helped prevent an accurate U.S. assessment of Japanese skills and tactics in naval night fighting. The U.S. was still unaware of the range and power of Japanese torpedoes, the effectiveness of Japanese night optics, and the skilled fighting ability of most Japanese destroyer and cruiser commanders. Incorrectly applying the perceived lessons learned from this battle, U.S. commanders in future naval night battles in the Solomons consistently tried to prove that American naval gunfire was more effective than Japanese torpedo attacks. This belief was severely tested just two months later during the Battle of Tassafaronga. A junior officer on Helena later wrote, "Cape Esperance was a three-sided battle in which chance was the major winner."[36]

Notes

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 310. Breakdown of U.S. deaths are: Boise- 107, Duncan- 48, Salt Lake City- 5, and Farenholt- 3.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 309. Frank breaks down the Japanese deaths as follows: Furutaka- 258, Aoba- 79, Fubuki- 78 (with 111 captured), Murakumo- 22, and Natsugumo- 17. Hackett says 80 were killed on Aoba in addition to Gotō and 33 were killed and 110 missing on Furutaka.

- ↑ Hogue, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, pp. 235–236.

- ↑ Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 14–15 and Shaw, First Offensive, p. 18. Henderson Field was named after Major Lofton R. Henderson, a Marine aviator killed during the Battle of Midway.

- ↑ Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 96–99, Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, p. 225.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 202, 210–211.

- ↑ Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 113–114.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 141–143, 156–158, 228–246, & 681.

- ↑ Rottman, Japanese Army, p. 61; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 152; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 224, 251–254, 266–268, & 289–290; Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, p. 225–226; and Smith, Bloody Ridge, pp. 132 & 158.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 293; Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 19–20; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 147–148; and Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, p. 225.

- ↑ Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 16 and 19–20; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 295–297; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 148–149; and Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, p. 225. Since not all of the Task Force 64 warships were available, Scott's force was designated as Task Group 64.2. The U.S. destroyers were from Squadron 12, commanded by Captain Robert G. Tobin in Farenholt.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 295–296; Hackett, HIJMS Aoba: Tabular Record of Movement; Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 31 and 57; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, p. 149–151; D'Albas, Death of a Navy, p. 183; and Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, p. 226. CombinedFleet.com states Jojima commanded the reinforcement convoy. Other accounts, however, state the commanding officer of Nisshin commanded the convoy and Jojima was not present. Jojima may have issued orders to the convoy from elsewhere in the Solomon Islands or from Rabaul.

- ↑ Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 31–32 and 57; Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 296; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 150–151; and Hackett, IJN Seaplane Tender Chitose.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp.295–296; Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 32–33; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 149–150. Frank says five of the Zero pilots were not recovered, but Cook says all but one was rescued.

- ↑ Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 19 and 31; Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 296; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, p. 150; Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, p. 226; and Hackett, IJN Seaplane Tender Chitose.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 293–294; Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 22–23, 25–27, and 37; and Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, p. 149.

- ↑ Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 25–29, 33, and 60; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 298–299; Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, p. 226; and Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 152–153.

- ↑ Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 20, 26, and 36; Frank, Guadalcanal, p.298; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 152–153.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 299; Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 58–60; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 152–153.

- ↑ Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 38–42, Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 299, Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 153–156.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 299–301, Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 42–43, 45–47, 51–53, Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 154–156.

- ↑ Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 42–50, 53–56, 71, Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 300–301, D'Albas, Death of a Navy, p. 184, Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, pp. 227–228, and Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 156–157.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 301–302, Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 68–70, 83–84, Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, pp. 226–227, D'Albas, Death of a Navy, p. 186, and Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 158–160.

- ↑ Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 70–77, Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 302, Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 158–160.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 302–304, Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 73–79, 83–86, Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, p. 228, Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 160–162.

- ↑ Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 80–84, 106–108, Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 303–304, Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 161–162.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 304–305, Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 74–75, 88–95, 100–105, Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, pp. 228–229, and Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 162–165.

- ↑ Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 96–97, Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 306, Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 163–166.

- ↑ Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 58, 97–98, 111, 120, Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 306–307, D'Albas, Death of a Navy, p. 187, Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, p. 229, and Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 168–169.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 307–308, Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 95–96, 108–110, 114–130, 135–138, Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 166–169.

- ↑ Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 111, 120–122, Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 308–309, Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, p. 169.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 309, Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 130–131, Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, p. 230, and Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, p. 169.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 309–312, Hackett, HIJMS Aoba, Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 169–171.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 311, Cook, Cape Esperance, pp. 140–144, Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 170–171.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 313–324, Cook, Cape Esperance, p. 150–151, Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, p. 230, and Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, p. 171.

- ↑ Cook, Cape Esperance, p. 59, 147–151, Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 310–312, Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 170–171.

References

- Cook, Charles O. (1992). The Battle of Cape Esperance: Encounter at Guadalcanal (Reissue ed.). Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-126-2.

- D'Albas, Andrieu (1965). Death of a Navy: Japanese Naval Action in World War II. Devin-Adair Pub. ISBN 0-8159-5302-X.

- Dull, Paul S. (1978). A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941–1945. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-097-1.

- Frank, Richard B. (1990). Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 0-14-016561-4.

- Griffith, Samuel B. (1963). The Battle for Guadalcanal. Champaign, Illinois, USA: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06891-2.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1958). "Chapter 8". The Struggle for Guadalcanal, August 1942 – February 1943, vol. 5 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-58305-7.

- Rottman, Gordon L.; Dr. Duncan Anderson (consultant editor) (2005). Japanese Army in World War II: The South Pacific and New Guinea, 1942–43. Oxford and New York: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-870-7.

Further reading

- Boehm, Roy (March 8, 1999). "Blood In The Water". Newsweek. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- Hone, Thomas C. (1981). "The Similarity of Past and Present Standoff Threats". Proceedings of the U.S. Naval Institute (Vol. 107, No. 9, September 1981). Annapolis, Maryland. pp. 113–116. ISSN 0041-798X

- Hornfischer, James D. (2011). Neptune's Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal. Random House. ISBN 0-553-80670-X.

- Kilpatrick, C. W. (1987). Naval Night Battles of the Solomons. Exposition Press. ISBN 0-682-40333-4.

- Lacroix, Eric; Linton Wells (1997). Japanese Cruisers of the Pacific War. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-311-3.

- Langelo, Vincent A. (2000). With All Our Might: The WWII History of the USS Boise (Cl-47). Eakin Pr. ISBN 1-57168-370-4.

- Lundstrom, John B. (2005). First Team And the Guadalcanal Campaign: Naval Fighter Combat from August to November 1942 (New ed.). Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-472-8.

- Miller, Thomas G. (1969). Cactus Air Force. Admiral Nimitz Foundation. ISBN 0-934841-17-9.

- Parkin, Robert Sinclair (1995). Blood on the Sea: American Destroyers Lost in World War II. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81069-7.

- Poor, Henry Varnum; Henry A. Mustin & Colin G. Jameson (1994). The Battles of Cape Esperance, 11 October 1942 and Santa Cruz Islands, 26 October 1942 (Combat Narratives. Solomon Islands Campaign, 4–5). Naval Historical Center. ISBN 0-945274-21-1.

- Morris, Frank Daniel (1943). "Pick out the biggest": Mike Moran and the men of the Boise. Houghton Mifflin Co.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Cape Esperance. |

- Hackett, Bob; Sander Kingsepp. "HIJMS Aoba: Tabular Record of Movement". Imperial Japanese Navy Page (CombinedFleet.com). Retrieved 2006-06-14.

- Hackett, Bob; Sander Kingsepp (1998–2006). "IJN Seaplane Tender Chitose: Tabular Record of Movement". Imperial Japanese Navy Page (CombinedFleet.com). Retrieved 2006-06-14.

- Hackett, Bob; Sander Kingsepp. "HIJMS Furutaka: Tabular Record of Movement". Imperial Japanese Navy Page (CombinedFleet.com). Archived from the original on 10 May 2006. Retrieved 2006-06-14.

- Hackett, Bob; Sander Kingsepp. "HIJMS Kinugasa: Tabular Record of Movement". Imperial Japanese Navy Page (CombinedFleet.com). Retrieved 2006-06-14.

- Horan, Mark. "Battle of Cape Esperance". Order of Battle. Archived from the original on 17 May 2006. Retrieved 2006-05-17.

- Hough, Frank O.; Ludwig, Verle E.; Shaw, Henry I., Jr. "Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal". History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. Archived from the original on 27 June 2006. Retrieved 2006-05-16.

- Lanzendörfer, Tim. "Stumbling Into Victory: The Battle of Cape Esperance". The Pacific War: The U.S. Navy. Retrieved 2006-05-16.

- Nevitt, Allyn D. (1998). "IJN Fubuki: Tabular Record of Movement". Imperial Japanese Navy Page (CombinedFleet.com). Retrieved 2006-06-14.

- Nevitt, Allyn D. (1998). "IJN Hatsuyuki: Tabular Record of Movement". Imperial Japanese Navy Page (CombinedFleet.com). Retrieved 2006-06-14.

- Nevitt, Allyn D. (1998). "IJN Murakumo: Tabular Record of Movement". Imperial Japanese Navy Page (CombinedFleet.com). Retrieved 2006-06-14.

- Nevitt, Allyn D. (1998). "IJN Natsugumo: Tabular Record of Movement". Imperial Japanese Navy Page (CombinedFleet.com). Archived from the original on 17 May 2006. Retrieved 2006-06-14.

- Office of Naval Intelligence (1943). "The Battle of Cape Esperance 11 October 1942". Combat Narrative. Publications Branch, Office of Naval Intelligence, United States Navy. Archived from the original on 13 May 2006. Retrieved 2006-05-17. – somewhat inaccurate on details, since it was written during the war

- Tobin, T. G. (October 23, 1942). "Report of Action off Savo Island, Solomons, Night of 11–12 October 1942.". Destroyer History Home Page (DestroyerHistory.org). Archived from the original on 2006-06-16. Retrieved 2006-06-14. – Copy of the commander of U.S. Destroyer Squadron 12's after action report.

- Tully, Anthony P. (2003). "IJN Nisshin: Tabular Record of Movement". Imperial Japanese Navy Page (CombinedFleet.com). Retrieved 2006-06-14.

Coordinates: 9°9′S 159°38′E / 9.150°S 159.633°E