Battle of Birch Coulee

| Battle of Birch Coulee | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Dakota War of 1862 | |||||||

Battlefield in 2010 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Santee Sioux | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Captain Hiram P Grant |

Gray Bird Red Legs Big Eagle Mankato | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 170 | ~200 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

13 killed 47 wounded 90 horses killed | 2 | ||||||

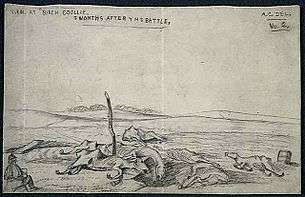

The Battle of Birch Coulee occurred September 2, 1862 during the Dakota War of 1862. After the Battle of Fort Ridgely and the Battle of New Ulm, Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley was planning to retaliate against the Sioux and to obtain the release of the settlers they were holding captive. While Sibley was training soldiers and attempting to organize supplies, he was reminded that the bodies of many settlers killed by the Indians still remained unburied on the battlefields. Sibley sent out a burial party of about 170 men from Fort Ridgely on August 31, 1862.

The battle

The troops, commanded by Captain Hiram P. Grant, left Fort Ridgely and continued to Redwood Ferry, stopping to bury about sixteen settlers' bodies along the way. Although some argue that Major Joseph Brown was in charge of the party, Brown's rank was little more than a paper commission given to Indian agents to increase their status among their Native charges. He held no military authority on the burial detail, as noted by first-hand accounts[1] which clearly indicate that Brown was with the party to look for members of his family, who had been taken prisoner by the Sioux, and to advise the detail with his expertise of the Indians. The following morning, Anderson and a group of cavalry crossed to the south side of the river, while Grant and his infantry stayed on the north side. At the end of the day, Anderson's and Grant's soldiers met up again at a campsite near Birch Coulee. The two detachments had buried 54 bodies, and since neither group had seen any Indians, they figured they were safe. Meanwhile, Chief Little Crow was leading a force of 110 northeastward from New Ulm, while his chief warrior, Gray Bird, was heading down the south side of the Minnesota River with a force of 350 Indians. Gray Bird's party and Brown's troops missed encountering each other during the day, but some Indian scouts discovered that Brown's troops were moving toward the campsite at Birch Coulee. The Sioux planned to ambush Brown's troops in the morning, thinking that only the cavalry was present and that they could be easily destroyed.

The Birch Coulee campsite was not easily defensible, since the Indians could approach from all sides and still remain under cover. Also, since the burial detail felt themselves safe, they did not take precautions against attack such as digging entrenchments and posting sentries far enough from camp to give ample warning. During the night, Gray Bird, along with chiefs Red Legs, Big Eagle, and Mankato crossed the Minnesota River and surrounded the camp. In the morning, the Indians commenced their ambush, wounding at least thirty United States soldiers and killing most of the cavalry's horses within the first few minutes. The heaviest part of the fight lasted about an hour, but the siege continued for many hours past then. Colonel Sibley could hear the sounds of the battle from Fort Ridgely, about sixteen miles away, so he sent out a relief party of 240 men. Colonel McPhail, heading up the relief party, thought he was almost completely surrounded by the Sioux and sent back for more reinforcements. Sibley returned with more reinforcements and an artillery brigade. The shelling forced the Sioux to disperse, and Sibley entered Brown's camp around 11 am on September 3. He encountered a "sickening sight", with twenty-two men and ninety horses dead, forty-seven men severely wounded, and others less severely hurt. The survivors were exhausted from a thirty-one hour siege without water or food.

Aftermath

The battle of Birch Coulee was the most deadly for the United States forces in the Dakota War of 1862. Colonel Sibley decided against taking responsibility for the disaster. In his military reports and in press dispatches he started to refer to the encounter as the 'attack on J.R. Brown's party.' The monument at Birch Coulee Battlefield correctly states that Captain Hiram P. Grant was in command, as do most first-hand accounts of the battle. Many historians mistakenly acknowledge that Brown was in command based on inaccurate reports written by Colonel Sibley. The battle may have distracted the Sioux from continuing down the Minnesota River toward more settlements, but the Americans forces learned that it was foolish to travel in hostile Indian territory with too few untrained troops.

Captain Joseph Anderson Company of Mounted Men "The Cullen Guard" went to the relief of New Ulm and was at the Battle of Birch Coulee. Casualties:

- Killed: 2nd Sergeant Robert Baxter; Privates Jacob Freeman;

- Died of Wounds: Private Richard Gibbons; Joseph Warren DeCamp

- Wounds: Farrier Thomas Barton {dangerously wounded}; Privates A.H. Bunker {wounded through both arms}; Peter Burkman {wounded in both thighs and ruptured}; James Buckingham {wounded through the left shoulder}; Geo Dashney {wounded in the right thigh}; John Martin.

The Birch Coulee battlefield is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.[2]

References

- ↑ Boyd, Robert. "Two Indian Battles". Hathi Trust. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ↑ National Park Service (2008-04-15). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- Carley, Kenneth (1976). The Sioux Uprising of 1862 (Second ed.). Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 0-87351-103-4.

External links

- Minnesota Historic Sites: Birch Coulee

- Explore Minnesota: Birch Coulee Battlefield

- Minnesota Encyclopedia article on the Battle of Birch Coulee