Battle of Armentières

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of Armentières (also Battle of Lille) was fought by German and Franco-British forces in northern France in October 1914, during reciprocal attempts by the armies to envelop the northern flank of their opponent, which has been called the Race to the Sea.[lower-alpha 1] Troops of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) moved north from the Aisne front in early October and then joined in a general advance with French troops further south, pushing German cavalry and Jäger back towards Lille until 19 October. German infantry reinforcements of the 6th Army arrived in the area during October.

The 6th Army began attacks from Arras north to Armentières in late October, which were faced by the BEF III Corps from Rouges Bancs, past Armentières north to the Douve river beyond the Lys. During desperate and mutually-costly German attacks, the III Corps, with some British and French reinforcements, was pushed back several times, in the 6th Division area on the right flank but managed to retain Armentières. The offensive of the German 4th Army at Ypres and the Yser was made the principal German effort and the attacks of the 6th Army were reduced to probes and holding attacks at the end of October, which gradually diminished during November.[lower-alpha 2]

Background

Strategic developments

From 17 September – 17 October, the belligerents had made reciprocal attempts to turn the northern flank of their opponent. Joffre ordered the French Second Army to move from eastern France to the north of the French Sixth Army from 2–9 September and Falkenhayn ordered the German 6th Army to move from the German-French border to the northern flank on 17 September. By the next day, French attacks north of the Aisne led to Falkenhayn ordering the Sixth Army to repulse French forces to secure the flank.[2] When the Second Army advanced it met a German attack, rather than an open flank on 24 September. By 29 September, the Second Army had been reinforced to eight corps but was still opposed by German forces near Lille, rather than advancing around the German northern flank. The German 6th Army had also found that on arrival in the north, it was forced to oppose a French offensive, rather than advance around an open northern flank and that the secondary objective of protecting the northern flank of the German armies in France had become the main task.[3]

Tactical developments

By 6 October the French needed British reinforcements to withstand German attacks around Lille. The BEF had begun to move from the Aisne to Flanders on 5 October and reinforcements from England assembled on the left flank of the Tenth Army, which had been formed from the left flank units of the Second Army on 4 October.[3] The Allies and the Germans, attempted to take more ground after the "open" northern flank had disappeared, the Franco-British attacks towards Lille in October, being followed up by attempts to advance between the BEF and the Belgian army by a new French Eighth Army. The moves of the 7th and then the 6th Army from Alsace and Lorraine had been intended to secure German lines of communication through Belgium, where the Belgian army had sortied several times during the period between the Franco-British retreat and the Battle of the Marne. In August British marines had landed at Dunkirk. In October a new 4th Army was assembled from the III Reserve Corps and the siege artillery used against Antwerp and four of the new reserve corps training in Germany.[4]

Prelude

Lille

The armament of the Lille fortress zone in 1914 consisted of 446 guns and 79,788 shells (including 3,000 × 75 mm), 9,000,000 rounds of rifle ammunition and 12 × 47 mm guns from Paris. During the Battle of Charleroi (21 August), General d'Amade garrisoned the area from Maubeuge to Dunkirk with a line of Territorial divisions. The 82nd Division held the area between the Escaut and the Scarpe, with advance posts at Lille, Deûlémont and Tournai, just over the Belgian border. The Territorials dug in but on 23 August, the BEF retreated from Mons and the Germans drove the 82nd Territorial Division out of Tournai. The German advance reached Roubaix and Tourcoing before a counter-attack by the 83rd and 84th regiments, that reoccupied Tournai during the night. Early on 24 August, the 170th Brigade organised the defence of the bridges over the Escaut but around noon, the Territorials were forced back by a German attack. The Mayor of Lille requested that Lille be declared an open city and at 5:00 p.m., the Minister of War ordered the garrison to leave the city and move between La Bassée and Aire-sur-la-Lys.[5][lower-alpha 3]

On 25 August, the German 1st Army reached the outskirts of Lille and General Herment withdrew the garrison. Maubeuge to the south was defended by 45,000 men and the Belgian army was still defending Antwerp to the north. On 2 September, German detachments entered Lille and left three days later; the town was intermittently occupied by patrols guarding the right flank of the 1st Army. After the German retreat from the Marne and the First Battle of the Aisne (13 September – 28 September), the northward manoeuvre known as the Race for the Sea commenced and on 3 October, Joffre formed the Tenth Army ( General de Maud'huy), to reinforce the northern flank of the French armies. When the XXI Corps arrived from Champagne, the 13th Division de-trained to the west of Lille. On the morning of 4 October, Chasseur battalions of the 13th Division moved to positions north and east of Lille.[5]

The 4th Chasseur Battalion advanced towards the suburb of Fives but was engaged by small-arms fire as it left the Lille ramparts. The Chasseurs drove the Germans back from the railway station and fortifications, taking several prisoners and some machine-guns. North of the town, the French met more German patrols near Wambrechies and Marquette and the 7th Cavalry Division skirmished in the neighbourhood of Fouquet. The new Lille garrison consisting of Territorial and Algerian mounted troops, took post to the south at Faches and Wattignies, linking with the rest of the 13th Division at Ronchin. A German attack reached the railway and on 5 October, a French counter-attack recaptured Fives, Hellemmes, Flers-lez-Lille, the fort of Mons-en-Barœul and Ronchin; to the west, cavalry engagements took place along the Ypres Canal. On 6 October, the 13th Division left two Chasseur battalions at Lille as XXI Corps moved south towards Artois and French cavalry near Deûlémont repulsed a German attack. On 7 October, the Chasseur battalions were withdrawn and the defence of Lille reverted to the Territorial and Algerian troops. From 9–10 October, the I Cavalry Corps engaged German troops between Aire-sur-la-Lys and Armentières but failed to re-open the road to Lille.[8]

At 10:00 a.m. on 9 October, a German aeroplane appeared over Lille and dropped two bombs on the General Post Office. In the afternoon, the Germans ordered all men from 18 to 48 years of age to the Béthune Gate, with instructions to leave Lille immediately.[8] Civilians from Lille, Tourcoing, Roubaix and neighbouring villages, left on foot for Dunkirk and Gravelines. Several died of exhaustion and others were taken prisoner by German Uhlans. The last train left Lille at dawn on 10 October, an hour after German artillery had begun to fire on the neighbourhood of the station, Prefecture and the Palais des Beaux Arts. After a lull since the previous afternoon, the bombardment resumed on 11 October from 9:00 a.m. until 1:00 a.m. and then continued intermittently. On 12 October, the garrison capitulated, by when 80 civilians had been killed, many fires had been started and the vicinity of the railway station destroyed. Five companies of Bavarian troops entered the town, followed throughout the day by Uhlans, Dragoons, artillery, Death's Head Hussars and infantry. [9]

Flanders terrain

The North-east of France and the south-west Belgium were known as Flanders. West of a line between Arras and Calais in the north-west, lay chalk downlands covered with soil sufficient for arable farming. East of the line, the land declines in a series of spurs into the Flanders plain, bounded by canals linking Douai, Béthune, Saint-Omer and Calais. To the south-east, canals ran between Lens, Lille, Roubaix and Courtrai, the Lys river from Courtrai to Ghent and to the north-west lay the sea. The plain was almost flat, apart from a line of low hills from Cassel, east to Mont des Cats, Mont Noir, Mont Rouge, Scherpenberg and Mount Kemmel. From Kemmel, a low ridge lay to the north-east, declining in elevation past Ypres through Wytschaete, Gheluvelt and Passchendaele, curving north then north-west to Dixmude where it merged with the plain. A coastal strip about 10 miles (16 km) wide, was near sea level and fringed by sand dunes. Inland the ground was mainly meadow, cut by canals, dykes, drainage ditches and roads built up on causeways. The Lys, Yser and upper Scheldt had been canalised and between them the water level underground was close to the surface, rose further in the autumn and filled any dip, the sides of which then collapsed. The ground surface quickly turned to a consistency of cream cheese and on the coast troops were confined to roads, except during frosts.[10]

The rest of the Flanders Plain was woods and small fields, divided by hedgerows planted with trees and cultivated from small villages and farms. The terrain was difficult for infantry operations because of the lack of observation, impossible for mounted action because of the many obstructions and difficult for artillery because of the limited view. South of La Bassée Canal around Lens and Béthune was a coal-mining district full of slag heaps, pit-heads (fosses) and miners' houses (corons). North of the canal, the city of Lille, Tourcoing and Roubaix formed a manufacturing complex, with outlying industries at Armentières, Comines, Halluin and Menin, along the Lys river, with isolated sugar beet and alcohol refineries and a steel works near Aire-sur-la-Lys. Intervening areas were agricultural, with wide roads on shallow foundations and unpaved mud tracks in France and narrow pavé roads along the frontier and in Belgium. In France, the roads were closed by the local authorities during thaws, to preserve the surface and marked by Barrières fermées, which were ignored by British lorry drivers. The difficulty of movement in the autumn absorbed much of the labour available on road maintenance, leaving field defences to be built by front-line soldiers.[11]

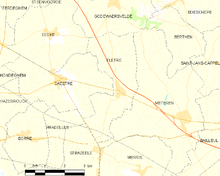

British offensive preparations

On 11 October, the British III Corps (Lieutenant-General William Pulteney), comprising the 4th and 6th divisions, arrived by rail at St. Omer and Hazebrouck and then advanced behind the left flank of II Corps, towards Bailleul and Armentières.[12] II Corps was to advance around the north of Lille and III Corps was to reach a line from Armentières to Wytschaete, with the Cavalry Corps on the left as far north as Ypres. French troops were to relieve the II Corps at Béthune, to move north and link with the right of III Corps but this did not occur. On the northern flank of III Corps, in front of the Cavalry Corps was a line of hills from Mont des Cats to Mt. Kemmel, about 400 feet (120 m) above sea level. Spurs ran south across the British line of advance and Mont des Cats and Flêtre were occupied by Höhere Kavallerie-Kommando 4 (HKK 4), with the 3rd, 6th and Bavarian Cavalry divisions, based on Bailleul. On 12 October, the British cavalry advanced to make room for III Corps and captured the Mont des Cats at dusk, having made combined attacks by hussars, lancers and a horse artillery battery during the day. Pulteney ordered III Corps to continue the advance on 13 October towards Bailleul, with the 6th Division on the right to move in three columns, on a line towards Vieux Berquin and Merris to the east of Hazebrouck and the 4th Division in two columns towards Flêtre, slightly north-east of Hazebrouck, with the Cavalry Corps advancing to the north east of the Mont des Cats.[13]

German offensive preparations

As Antwerp fell on 9 October, Falkenhayn ordered the III Reserve Corps (5th and 6th Reserve divisions and 4th Ersatz Division) westwards in pursuit of the Belgian army. With the fall of the fortress and the arrival of Franco-British forces in the area between Lille and Dunkirk, Falkenhayn ordered the 4th Army headquarters to Flanders from Lorraine and the assembly of a new army with the XXII, XXIII, XXVI and XXVII Reserve corps, to break through the Allied forces between Menin and the sea.[14] German cavalry of HKK 4 operating to the north of the 6th Army, had probed north-west as far as Ypres and towards Estaires in the Lys valley, then retired south across the Lys near Armentières, before moving south-west through Bailleul and Frelinghien to Laventie. The 3rd Cavalry Division found the road to Estaires blocked and 6th Cavalry Division moved through Deûlémont and Radinghem-en-Weppes to Prémesques and Fleurbaix. A skirmish occurred with French Chasseurs but reinforcements arrived to drive them off and c. 3,000 Belgian reservists were captured. The moves of the German cavalry united the divisions of HKK 4 with HKK 1 and HKK 2 but with so little room for manoeuvre, HKK 4 was sent north of the Lys on 11 October. Next day, HKK 4 was ordered onto the defensive as British and French cavalry advanced from the west.[15] The 6th Army had arrived piecemeal from Lorraine, the VII Corps deploying from La Bassée towards Armentières; on 15 October the XIX Corps arrived opposite Armentières, followed by the XIII Corps from Warneton to Menin. British attacks by II Corps and III Corps against the German VII and XIX corps led to the XIII Corps being moved south as a reinforcement opposite the junction of the II and III corps.[14]

After HKK 4 moved south of the Lys again on the night of 14/15 October, the 3rd Cavalry Division concentrated around Armentières, with the 6th Cavalry Division to the west and the Bavarian Cavalry Division around Sailly-sur-la-Lys and then withdrew to an area between Armentières and Laventie a day later, before being replaced by infantry units of the 6th Army as they arrived and retiring to Lille. As XIX Corps occupied Lille on 12 October, each side began a final effort to round the northern flank of its opponent. With Lille secure, the 6th Army moved the XIII Corps west around Lille, units of the 26th Division moving north of the town to occupy Menin on 14 October and began a march towards Ypres. Patrols reached Gheluvelt and Becelaere as British forces began to advance eastwards from Ypres, which according to the plans laid by Falkenhayn, were not to be opposed but allowed to advance into a trap to be sprung by the 4th Army as it advanced from Ghent into the flank and rear of the Allied armies.[16] As the 6th Army was to operate defensively during this period, more infantry was needed in the south of the army area. Falkenhayn ordered the right flank units to form a defensive flank in the north, from La Bassée to Armentières and Menin, coinciding with a growing artillery ammunition shortage, which reduced the offensive capacity of the 6th Army in any case. XIX Corps was ordered to send the 40th Division round the north of Armentières and the 24th Division to the south, which led to several engagements with the British 4th Division near Le Gheer and Ploegsteert. By 15 October, the infantry regiments of the 40th Division had reached the Lys and deployed southwards from Warneton to La Basseville and Frélinghien. The infantry dug in on rises to gain a better view of the surroundings. Soon afterwards, outposts were established at Pont Rouge and Le Touquet, to coincide with a general attack by the 4th Army further north.[16]

Battle

BEF offensive, 13–19 October

The 4th and 6th divisions advanced on 13 October and found German troops dug in along the Meterenbecque. A corps attack from La Couronne to Fontaine Houck began at 2:00 p.m. in wet and misty weather, which by evening had captured Outtersteene and Méteren, at a cost of 708 casualties. On the right, the French II Cavalry Corps (de Mitry) attempted to support the attack but with no howitzers could not advance in level terrain, which was dotted with cottages improvised as strong points by the Germans; on the northern flank the British cavalry took Mont Noir near Bailleul. The German defenders slipped away from well-sited defences, which had been dug in front of houses, hedges and walls, to keep the soldiers invisible, earth having been scattered rather than used for a parapet, which would have been seen. Lille had fallen on 12 October, which revealed the presence of the German XIX Corps; air reconnaissance by the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) reported that long columns of German infantry, were entering Lille from Douai and leaving on the road to Armentières. It was planned that III Corps would attack the next German line of defence, before German reinforcements could reach the scene. On 14 October, rain and mist made air reconnaissance impossible but patrols found that the Germans had fallen back beyond Bailleul and crossed the Lys. The German 6th Army had been ordered to end its attacks from La Bassée to Armentières and Menin, until the new 4th Army had moved through Belgium and prolonged the German northern flank from Menin to the sea.[17]

During the day, the Allied forces completed a weak but continuous line to the North Sea, when Allenby's cavalry linked with the 3rd Cavalry Division south of Ypres. The infantry reached a line from Steenwerck to Dranoutre, after a slow advance against German rearguards, in poor visibility and close country. By evening Bailleul and Le Verrier were occupied and next day, an advance to the Lys began, against German troops and cavalry fighting delaying actions. The III Corps closed up to the river at Sailly, Bac St. Maur, Erquinghem and Pont de Nieppe, linking with the cavalry at Romarin. On 16 October, the British secured the Lys crossings and late in the afternoon, German attacks began further north at Dixmude. Next day the III Corps occupied Armentières and on 18 October, the III Corps was ordered to participate in an offensive by the BEF and the French army, by attacking down the Lys valley. Part of Pérenchies ridge was captured but much stronger German defences were encountered and the infantry were ordered to dig in.[17] On 18/19 October the III Corps held a line from Radinghem to Pont Rouge, west of Lille.[18]

German 6th Army offensive, October–November

20 October

On 19 October, Pulteney had ordered III Corps to dig in and collect as many local and divisional reserves as possible. German attacks against the 6th Division, holding a line from Radinghem to Ennetières, Prémesques and Epinette began after a one-hour bombardment from 7:00 a.m. by heavy guns and howitzers.[lower-alpha 4] The German attack was part of an offensive either side of Ypres, intended to encircle the British forces. The 6th Army attacked with the XIV, VII, XIII and XIX corps, intending to break through the Allied defences from Arras to La Bassée and Armentières.[lower-alpha 5] German infantry advanced in rushes of men in skirmish lines, covered by machine-gun fire. To the south of the 18th Brigade, a battalion of the 16th Brigade had dug in east of Radinghem while the other three dug a reserve line from Bois Blancs to Le Quesne, La Houssoie and Rue du Bois, half-way back to Bois Grenier. A German attack by the 51st Infantry Brigade at 1:00 p.m. was repulsed but the battalion fell back to the eastern edge of the village, when the German attack further north at Ennetières succeeded.[20] The main German attack was towards a salient at Ennetières held by the 18th Brigade, in disconnected positions held by advanced guards, ready for a resumption of the British advance. The brigade held a front of about 3 miles (4.8 km) with three battalions and was attacked on the right flank where the villages of Ennetières and La Vallée merged. The German attack was repulsed by small-arms fire and little ground was gained by the Germans, who were attacking across open country with little cover.[21]

Another attack was made on Ennetières at 1:00 p.m. and repulsed but on the extreme right of the brigade, five platoons were spread across 1,500 yards (1,400 m) to the junction with the 16th Brigade. The platoons had good observation to their fronts but were not in view of each other and in a drizzle of rain, the Germans attacked again at 3:00 p.m.[21] The German attack was repulsed with reinforcements and German artillery began a bombardment of the Brigade positions from the north-east until dark, then sent about three battalions of the 52nd Infantry Brigade of the 25th Reserve Division forward in the dark, to rush the British positions. The German attack broke through and Ennetières was entered by two companies of Reserve Infantry Regiment 125 from the west, four companies of Reserve Infantry Regiment 122 and a battalion of Reserve Infantry Regiment 125 broke in from the south, the British platoons being surrounded and captured. Another attack from the east, led to the British infantry east of the village retiring to the west side of the village, where they were surprised and captured by German troops advancing from La Vallée, which had fallen after 6:00 p.m. and who had been thought to be British reinforcements; some of the surrounded troops fought on until 5:15 a.m. next morning. The German infantry did not exploit the success and British troops on the northern flank were able to withdraw to a line 1-mile (1.6 km) west of Prémesques, between La Vallée and Chateau d'Hancardry.[22]

To the north of the 18th Brigade, a battalion of the 17th Brigade held a line from Epinette to Prémesques and Mont des Prémesques, which was bombarded by German artillery from 2:00–8:00 a.m. and then attacked by the 24th Division of XIX Corps, which captured Prémesques and attracted most of the reserves of the 6th Division to the left flank of its front. A defensive flank was formed after the loss of the village, which was able to prolong the defence of Mont des Prémesques, which fell at 4:30 p.m. An 11th Brigade battalion from the 4th Division, was sent forward for a counter-attack but this was then over-ruled by Pulteney, since with the loss of Ennetières and Prémesques a much larger attack was needed and there were insufficient troops available. After dark the 6th Division was ordered back to a shorter line from Touquet to Bois Blancs, Le Quesne, La Houssoie, Chateau d'Hancardry to ground about 400 yards (370 m) west of Epinette, the retirement on the right and centre being about 2 miles (3.2 km). The division had suffered c. 2,000 losses, 1,119 in the 18th Brigade but Kier was confident that the division could hold on, when the 19th Brigade and the French I Cavalry Corps arrived on the right flank during the day.[23]

On the 4th Division (Major-General H. F. M. Wilson) front to the north, a German bombardment by heavy artillery began on Armentières at 8:00 a.m. which led to the III Corps headquarters being moved back to Bailleul. Despite the orders from Pulteney for III Corps to dig in, the 4th Division was allowed to continue the attack towards Frélinghien, to gain better communications across the Lys and the 10th Brigade attacked at dawn. Trenches and houses on the southern fringe of the village were captured and fifty prisoners taken from the 89th Brigade of the 40th Division, XIX Corps but the attack used up the stock of high explosive ammunition and the attack was suspended. Towards the left of the division, the 12th Brigade, in front of Ploegsteert Wood (Plugstreet Wood) near Le Gheer was attacked from midday and as dark fell a determined German rush got forward to within 300–500 yards (270–460 m) of the British line and dug in. During the afternoon Pulteney had ordered the division to hold its advanced position if possible but not to retire further than the main line and during the evening, Lieutenant-General E. Allenby the Cavalry Corps commander requested support at Messines to the north, which with the news of the retirement of the 6th Division, left Wilson and the 4th Division in some apprehension about both flanks.[24]

21 October

The III Corps received orders from French to remain on the defensive along with II Corps, the Cavalry Corps and the 7th Division, while I Corps attacked; the trenches of III Corps were bombarded from the early morning of 21 October, particularly around Frélinghien. Two battalions of the 11th Brigade and two companies of the 12th Brigade were ordered north, to reinforce the Cavalry Corps at Hill 63, to occupy the north-west of Ploegsteert Wood as a northern flank guard. A battalion was detached to the 12th Brigade at Le Gheer during the move. Only one battalion was available, because of the need to send battalions to weak points in the line, since the corps was holding a 12-mile (19 km) line, while under attack by two German corps. At 5:15 a.m. under cover of the morning mist, the Germans attacked the 12th Brigade at Le Gheer and overran the defences of a battalion on the left, that retreated for 400 yards (370 m). When established in Le Gheer, the German infantry fired on the British defences to the south, nearly caused a panic and outflanked the Cavalry Corps to the north from St. Yves to Messines. A counter-attack was made just after 9:00 a.m. by one battalion and two squadrons of lancers, which drove back the Germans and inflicted many losses, regaining the captured trench, except near the village of Le Touquet.[25]

Forty-five British prisoners were liberated and 134 German prisoners taken. More attacks were made to complete the recapture of the rest of the trench during the day and at dusk two companies succeeded, the 12th Brigade losing 468 casualties in the fighting. German infantry made demonstrations on the rest of the 4th Division front into the night but did not attack again. Concern at General Headquarters about the state of the Cavalry Corps to the north, led to III Corps being ordered to provide reinforcements and two infantry companies and part of an engineer company were sent to Messines in the afternoon. The 12th Brigade moved its left boundary from the Lys to the Warnave stream near Ploegsteert Wood and the 11th Brigade took over part of the wood, which shortened the Cavalry Corps line by 1-mile (1.6 km). Despite frequent bombardment, no German attacks were made on the 6th Division front during the day, then at 6:00 p.m. the centre of the division was attacked by Reserve Infantry Regiment 122 of the 25th Reserve Division, which was repulsed. German infantry seen alighting from trains on the La Vallée–Armentières line were engaged with machine-gun fire and German field artillery firing from near Ennetières were driven off.[26]

On the southern flank of III Corps around Fromelles, the 19th Brigade and the French cavalry took over, with the British occupying the north end of the gap between II and III corps from Le Maisnil to Fromelles and the French from the south of the village to Aubers and the junction with the 3rd Division. Around 11:00 a.m. German artillery began to bombard Le Maisnil as part of an attack on II Corps to the south. In the afternoon the village was attacked until nightfall, when a gap was forced in the Anglo-French defences and the defenders of Le Maisnil withdrew about 1,200 yards (1,100 m) to a reserve position at Bas Mesnil, leaving behind 300 men who were taken prisoner, including their wounded. The retirement was assisted by French artillery-fire, which slowed the German advance despite a 2-mile (3.2 km) gap and the isolation of a battalion near Fromelles. At midnight the 19th Brigade fell back to a line from Rouges Bancs to La Boutillerie and dug in. German troops of Infantry Regiments 122 and 125 of the 26th Division appeared to be unaware of the retirement, having strayed southwards after the capture of La Vallée earlier in the day.[27]

22–25 October

In the 6th Division area, field defences were far less developed than on the 4th Division front, since piecemeal retirements had led to positions being abandoned and new ones dug from scratch several times, from which artillery observation was unsatisfactory. Many German attacks were made from 22–23 October, particularly against the 16th Brigade, which held a south-facing salient with Le Quesne at the apex, 3 miles (4.8 km) south-east of Armentières. At dawn on 23 October, a bold German force infiltrated in a dawn mist and were only repulsed after costly hand-to-hand fighting. The 10th Brigade extended its front south to La Chapelle-d'Armentières, taking over from the 12th Brigade, which was moved into reserve at the divisional boundary and then on 24 October, the brigade relieved the 17th Brigade of the 6th Division as far as Rue du Bois, extending the 4th Division front to 8 miles (13 km).[28] By 22 October III Corps and the 19th Brigade held a line between French and British cavalry units, about 12 miles (19 km) long from Rouges Bancs, 5 miles (8.0 km) south-west of Armentières to Touquet, La Houssoie, Epinette, Houplines, Le Gheer, St. Yves and the Douve river, facing the bulk of the German XIII Corps with the 48th Reserve Division in reserve, XIX Corps and I Cavalry Corps. The XIII Corps had begun moving southwards from Menin on 18 October and had attacked the 19th Brigade at Radinghem on 21 October. It was anticipated that it would attack the area between III Corps and II Corps, which it did on 23 October and drove out the French from Fromelles, leaving the right flank of III Corps dangerously exposed until 24 October, when the Jullundur Brigade of the Lahore Division arrived and filled the gap, the French I Cavalry Corps going back into reserve.[29]

French gave orders for the III Corps to dig in and maintain its positions, which was relatively easy for the 4th Division, after the recapture of Le Gheer on 20/21 October, because German activity was limited to artillery-fire, sniping and minor attacks until 29 October. Opinion in the 4th Division was that with rifle-fire, machine-gun fire from the flanks and artillery crossfire, any German attack could be repulsed. Control of the artillery was centralised, to be brought to bear on the divisional front and further north in the Cavalry Corps area at Messines.[29] As dawn broke on 24 October, the 6th Army made a general attack from La Bassée Canal to the Lys and on the III Corps front was repulsed, except on the 16th Brigade front, which was enfiladed from the east. German troops used the cover of factory buildings to advance and overran one battalion front, until pushed back by a counter-attack. The battle continued all day and around midnight, the 16th and 18th brigade commanders agreed to a withdrawal of the 16th Brigade, for about 500 yards (460 m) to a reserve line, dug from Touquet to Flamengrie Farm if the Germans attacked again. Soon after midnight on 24/25 October, another determined German attack began and during the night of 25/26 October, the 16th Brigade stole away in the dark and rain; from 24–26 October, the 16th Brigade had lost 585 casualties.[30]

26 October – 2 November

From 25–26 October, the III Corps positions were subjected to German artillery bombardments and sniper fire but no infantry attacks. The division used the respite to dig deeper, build communication trenches and to withdraw troops from the front line into reserve, ready for local counter-attacks. After another big artillery bombardment on 27 October, the 6th Division was attacked and the 16th and 18th brigades repulsed the Germans and inflicted many casualties. A bigger German attack was made at dawn on 28 October, on an 18th Brigade battalion holding a salient east of the La Bassée–Armentières railway near Rue du Bois by infiltrating through ruined buildings. The German infantry of the XIII Corps divisions and Infantry regiments 107 and 179 from XIX Corps, overran the British battalion but were then counter-attacked and forced back, leaving many casualties behind. A lull followed on 28 October, until 2:00 a.m. on 29 October, when the 19th Brigade was attacked south of La Boutillerie, which failed except for the loss of part of the front trench, until the brigade reserve arrived and forced back the Germans, forty prisoners being taken from the 48th Reserve Division of the XXIV Corps, which had been moved into line between the XIX and XIII corps.[31]

The III Corps was confronted by 4–5 German divisions, that had made numerous general and probing attacks but the situation up north around Ypres, began to have repercussions. On 30 October, French ordered the corps to move all the reserves of the 4th Division north of the Lys to reinforce the Cavalry Corps, with the 6th Division organising its reserves to cover the 4th Division positions south of the river. By coincidence, big 6th Army attacks on the 4th Division front south of the river ended at the same time, which meant that the massing of reserves on the north bank could be done safely. On the north bank, a dawn bombardment was followed by a German attack on the 11th Brigade front, where one battalion was spread along 2,000 yards (1,800 m) from Le Gheer to the Douve river. No continuous trenches existed and the isolated strong-points had no communication trenches. Infantry Regiment 134 of the 40th Division began to overrun the battalion, until a counter-attack by the brigade reserve pushed the Germans back. An attack on 31 October, reached the British trenches again but the Germans retired before a counter-attack could be mounted. A battalion of the 12th Brigade from the 4th Division took over the right flank of the Cavalry Corps line, which brought the divisional front north to Messines.[32]

During November, artillery-fire, sniping and local attacks continued south of the Lys and on 1 November, the Cavalry Corps was forced out of Messines, which left the northern flank of III Corps exposed, at a time when the corps was defending a 12-mile (19 km) front with severely depleted units. Few reserves were left and Pulteney reported to the BEF headquarters, that the corps could not withstand another big attack. French sent two battalions north from II Corps and gave permission for the corps to retreat to a reserve line from Fleurbaix to Nieppe and Neuve Eglise if necessary. The daily ration of artillery ammunition was doubled from forty rounds per day for each 18-pounder and twenty per day for each 4.5-inch howitzer, which enabled the 4th and 6th divisions to maintain their front. The Battle of Armentières ended officially on 2 November but north of the Lys, fighting in the 4th Division positions up to the Douve river continued and are described in the Battle of Messines (1914).[33]

Aftermath

Analysis

| Month | Losses | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| August | 14,409 | ||

| September | 15,189 | ||

| October | 30,192 | ||

| November | 24,785 | ||

| December | 11,079 | ||

| Total | 95,654 | ||

The battles in French and Belgian Flanders were the last battles of encounter and manoeuvre on the Western front, until 1918. After the meeting engagements, the battles became a desperate defence by the British, French and Belgian armies against the offensives of the German 6th and 4th armies. No defensive system like those built in 1915 existed and both sides improvised shelter pits and short lengths of trench, which were repaired each night. Artillery was concealed by ground features only but the small number of observation aircraft on both sides and the extent of tree cover, enabled guns to remain hidden.[35] The attack by the 6th Army on 21 October, from La Bassée to St. Yves by the VII, XIII and XIX corps achieved only small advances against the 6th Division and the XIX Corps attack on the 4th Division front gained no ground but the attacks put great strain on the British defence and prevented reserves from being transferred north to Ypres.[36] British artillery adopted the French practice of night artillery fire on German communication routes, as far as 6-inch gun ammunition allowed.[37]

The German forces in Flanders were homogeneous and had unity of command, against a composite force of British, Indian, French and Belgian troops, with different languages, training, tactics, equipment and weapons. German discipline and bravery was eventually defeated by the dogged resistance of the Allied soldiers, the effectiveness of French 75 mm field guns, British skill at arms, skilful use of ground and the use of cavalry as a mobile reserve. Bold counter-attacks by small numbers of troops in reserve, drawn from areas less threatened, often had an effect disproportionate to their numbers. German commentators after the war like Oberstleutnant (Lieutenant-Colonel) Konstantin Hierl criticised the slowness of the 6th Army in forming a strategic reserve, that could have been achieved by 22 October, rather than 29 October and claimed that generals had "attack-mania", in which offensive spirit and offensive tactics were often confused.[38]

Casualties

From 15–31 October the III Corps lost 5,779 casualties, 2,069 men from the 4th Division and the remainder from the 6th Division.[33] German casualties in the Battle of Lille from 15–28 October, which included the ground defended by III Corps, were 11,300 men. Total German losses from La Bassée to the sea from 13 October – 24 November were 123,910.[39]

Notes

- ↑ According to the findings of the Battles Nomenclature Committee of 9 July 1920, four simultaneous battles occurred in October and November 1914. The Battle of La Bassée (10 October – 2 November) from the Beuvry–Béthune road to a line from Estaires to Fournes, the Battle of Armentières (13 October – 2 November) from Estaires to the Douve river, the Battle of Messines (12 October – 2 November) from the Douve to the Ypres–Comines Canal and the Battles of Ypres (19 October – 22 November), comprising the Battle of Langemarck (21–24 October), the Battle of Gheluvelt (29–31 October) and the Battle of Nonne Bosschen (11 November), from the Ypres–Comines Canal to Houthulst Forest. J. E. Edmonds, the British Official Historian, wrote that the II Corps battle at La Bassée could be taken as separate but that the other battles from Armentières to Messines and Ypres, were better understood as a battle in two parts, an offensive by III Corps and the Cavalry Corps from 12–18 October, against which the Germans retired and the offensive by the German 6th and 4th armies 19 October – 2 November, which from 30 October mainly took place north of the Lys at Armentières, from when the battles of Armentières and Messines merged with the Battles of Ypres.[1]

- ↑ Traditional British military spelling of French and Belgian places, have been used in this article.

- ↑ Lille lies between the rivers Lys, Escaut and Scarpe, in the plain before the hills of Artois, between Maubeuge and the port of Dunkirk. In 1873, General Séré de Rivières, Director of the Engineering Section at the Ministry of War, began a programme of fortress-building, to reorganise the defences of the northern frontier, with Lille as one of the pivots.[6] At the end of the century, the fortifications were allowed to become derelict and by July 1914, 3,000 gunners and nearly a third of the guns had been removed. On 1 August, the Governor, General Lebas, received orders to consider Lille an open city but on 21 August, his successor General Herment, reinforced the garrison from 15,000–25,000 and then to 28,000 men, drawing units from each regiment in the 1st Region.[7]

- ↑ This section of the article is mainly derived from English language sources, which go into far less detail about German troops dispositions and intentions. German sources exist but are either not translated into English or were not available at the time of writing (September 2014).

- ↑ From 20–22 October, the German cavalry was reorganised into the I Cavalry Corps with the Guard and 4th Cavalry divisions, the IV Cavalry Corps with the 6th and 9th Cavalry divisions and the V Cavalry Corps with the 3rd and Bavarian Cavalry divisions, under the command of Lieutenant-General von Hollen. The cavalry were instructed to pin down the forces in front of them and as the XIX Corps attacked from the east, to attack the flank and rear of the opposing forces.[19]

Footnotes

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Foley 2005, p. 101.

- 1 2 Doughty 2005, pp. 98–100.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 269–270.

- 1 2 Michelin 1919c, p. 5.

- ↑ Michelin 1919c, p. 3.

- ↑ Michelin 1919c, p. 4.

- 1 2 Michelin 1919c, p. 6.

- ↑ Michelin 1919c, p. 7.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 74–76.

- ↑ Edmonds 1926, p. 408.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 94–96.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1925, pp. 121–122.

- ↑ Sheldon 2010, pp. 23–26.

- 1 2 Sheldon 2010, pp. 33–39.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1925, pp. 95–98.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 98–123.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, p. 169.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 138, 141.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1925, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 139–141.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 114–142.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 142–143.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 148–150.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 150–151.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 151–152.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, p. 227.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1925, pp. 225–226.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 227–228.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 228–229.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, p. 230.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1925, p. 231.

- ↑ War Office 1922, p. 253.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 460–461.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, p. 171.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, p. 463.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, p. 464.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, p. 468.

References

- Doughty, R. A. (2005). Pyrrhic Victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. ISBN 0-67401-880-X.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1926). Military Operations France and Belgium 1914: Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne August–October 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962523.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1925). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914: Antwerp, La Bassée, Armentières, Messines and Ypres October–November 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (1st ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 220044986.

- Foley, R. T. (2007) [2005]. German Strategy and the Path to Verdun : Erich Von Falkenhayn and the Development of Attrition, 1870–1916. Cambridge: CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-04436-3.

- Lille, Before and During the War (PDF). Michelin's Illustrated Guides to the Battlefields (1914–1918) (English ed.). London: Michelin. 1919. OCLC 629956510. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- Sheldon, J. (2010). The German Army at Ypres 1914 (1st ed.). Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84884-113-0.

- Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War, 1914–1920 (PDF). London: HMSO. 1922. OCLC 610661991. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- Strachan, H. (2001). The First World War: To Arms. I. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926191-1.

Further reading

- Books

- Beckett, I. (2006) [2003]. Ypres The First Battle, 1914 (repr. ed.). London: Longmans. ISBN 1-4058-3620-2.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1922). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914: Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne August–October 1914 (PDF). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (1st ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962523. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- Kingston, G. P. (2006). History of the 4th (British) Infantry Division, 1914–1918. London: The London Press. ISBN 1-905006-15-2.

- Marden, T. O. (1920). A Short History of the 6th Division August 1914 – March 1919 (PDF). London: Hugh Rees. ISBN 1-43753-311-6. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- Encyclopaedias

- The Times History of the War (PDF). II. London: The Times. 1914–1922. OCLC 220271012. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Armentières. |

- The Battles of La Bassée, Messines and Armentières

- Armentieres

- Battle of Armentières, 13 October – 2 November 1914