Barium titanate

| Polycrystalline BaTiO3 in plastic | |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| 12047-27-7 | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| ChemSpider | 10605734 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.031.783 |

| PubChem | 6101006 |

| RTECS number | XR1437333 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| BaTiO3 | |

| Molar mass | 233.192 g |

| Appearance | white crystals |

| Odor | odorless |

| Density | 6.02 g/cm3, solid |

| Melting point | 1,625 °C (2,957 °F; 1,898 K) |

| insoluble | |

| Solubility | slightly soluble in dilute mineral acids; dissolves in concentrated hydrofluoric acid |

| Band gap | 3.2 eV (300 K, single crystal)[1] |

| Refractive index (nD) |

no2.412; ne=2.360[2] |

| Structure | |

| Tetragonal, tP5 | |

| P4mm, No. 99 | |

| Hazards | |

| R-phrases | R20/22 |

| S-phrases | S28A, S37, and S45 |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Barium titanate is the inorganic compound with the chemical formula BaTiO3. Barium titanate is a white powder and transparent as larger crystals. This titanate is a ferroelectric ceramic material, with a photorefractive effect and piezoelectric properties. It is used in capacitors, electromechanical transducers and nonlinear optics.

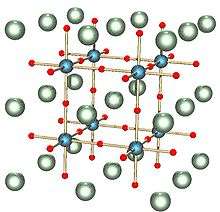

Structure

The solid can exist in five phases, listing from high temperature to low temperature: hexagonal, cubic, tetragonal, orthorhombic, and rhombohedral crystal structure. All of the phases exhibit the ferroelectric effect except the cubic phase. The high temperature cubic phase is easiest to describe, consisting of octahedral TiO6 centres that define a cube with Ti vertices and Ti-O-Ti edges. In the cubic phase, Ba2+ is located at the center of the cube, with a nominal coordination number of 12. Lower symmetry phases are stabilized at lower temperatures, associated with the movement of the Ba2+ to off-center position. The remarkable properties of this material arise from the cooperative behavior of the Ba2+ centres.

Production and handling properties

Barium titanate can be synthesized by the relatively simple sol–hydrothermal method.[3] Barium titanate can also be manufactured by heating barium carbonate and titanium dioxide. The reaction proceeds via liquid phase sintering. Single crystals can be grown around 1100 °C from molten potassium fluoride.[4] Other materials are often added for doping, e.g. to give solid solutions with strontium titanate. Reacts with nitrogen trichloride and produces a greenish or grey mixture, the ferroelectric properties of the mixture are still present in this form.

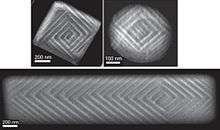

Much work has been dedicated to its morphology. Fully dense nanocrystalline barium titanate has 40% higher permittivity than the same material prepared in classic ways.[5] The addition of inclusions of barium titanate to tin has been shown to produce a bulk material with a higher viscoelastic stiffness than that of diamonds. Barium titanate goes through two phase transitions that change the crystal shape and volume. This phase change leads to composites where the barium titanates have a negative bulk modulus (Young's modulus), meaning that when a force acts on the inclusions, there is displacement in the opposite direction, further stiffening the composite.[6]

Like many oxides, barium titanate is insoluble in water but attacked by sulfuric acid. Its bulk room-temperature bandgap is 3.2 eV, but it increases to ~3.5 eV when the particle size is reduced from about 15 to 7 nm.[1]

Uses

Barium titanate is a dielectric ceramic used for capacitors. BaTiO3 ceramics with a perovskite structure are capable of dielectric constant values as high as 7,000; other ceramics, such as titanium dioxide (TiO2), have values between 20 and 70. Over a narrow temperature range, values as high as 15,000 are possible; most common ceramic and polymer materials are less than 10.[8]

It is a piezoelectric material for microphones and other transducers. The spontaneous polarization of barium titanate single crystals at room temperature range between 0.15 C/m2 in earlier studies,[9] and 0.26 C/m2 in more recent publications,[10] and its Curie temperature is between 120 and 130 °C. The differences are related to the growth technique, with earlier flux grown crystals being less pure than current crystals grown with the Czochralski process,[11] which therefore have a larger spontaneous polarization and a higher Curie temperature.

As a piezoelectric material, it was largely replaced by lead zirconate titanate, also known as PZT. Polycrystalline barium titanate displays positive temperature coefficient, making it a useful material for thermistors and self-regulating electric heating systems.

Barium titanate crystals find use in nonlinear optics. The material has high beam-coupling gain, and can be operated at visible and near-infrared wavelengths. It has the highest reflectivity of the materials used for self-pumped phase conjugation (SPPC) applications. It can be used for continuous-wave four-wave mixing with milliwatt-range optical power. For photorefractive applications, barium titanate can be doped by various other elements, e.g. iron.[12]

Thin films of barium titanate display electrooptic modulation to frequencies over 40 GHz.[13]

The pyroelectric and ferroelectric properties of barium titanate are used in some types of uncooled sensors for thermal cameras.

High purity barium titanate powder is reported to be a key component of new barium titanate capacitor energy storage systems for use in electric vehicles.[14]

Natural occurrence

Barioperovskite is a very rare natural analogue of BaTiO3, found as microinclusions in benitoite.[15]

See also

References

- 1 2 Suzuki, Keigo; Kijima, Kazunori (2005). "Optical Band Gap of Barium Titanate Nanoparticles Prepared by RF-plasma Chemical Vapor Deposition". Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 44 (4A): 2081–2082. doi:10.1143/JJAP.44.2081.

- ↑ Tong, Xingcun Colin (2013). Advanced Materials for Integrated Optical Waveguides. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 357. ISBN 978-3-319-01550-7.

- ↑ Selvaraj, M.; Venkatachalapathy, V.; Mayandi, J.; Karazhanov, S.; Pearce, J. M. (2015). "Preparation of meta-stable phases of barium titanate by Sol-hydrothermal method". AIP Advances. 5 (11): 117119. doi:10.1063/1.4935645.

- ↑ Galasso, Francis S. (1973). Barium Titanate, BaTiO3. Inorganic Syntheses. 14. pp. 142–143. doi:10.1002/9780470132456.ch28. ISBN 9780470132456.

- ↑ Nyutu, Edward K.; Chen, Chun-Hu; Dutta, Prabir K.; Suib, Steven L. (2008). "Effect of Microwave Frequency on Hydrothermal Synthesis of Nanocrystalline Tetragonal Barium Titanate". The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 112 (26): 9659. doi:10.1021/jp7112818.

- ↑ Jaglinski, T.; Kochmann, D.; Stone, D.; Lakes, R. S. (2007). "Composite materials with viscoelastic stiffness greater than diamond". Science. 315 (5812): 620–2. doi:10.1126/science.1135837. PMID 17272714.

- ↑ Scott, J. F.; Schilling, A.; Rowley, S. E.; Gregg, J. M. (2015). "Some current problems in perovskite nano-ferroelectrics and multiferroics: Kinetically-limited systems of finite lateral size". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 16 (3): 036001. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/16/3/036001. PMC 5099849

. PMID 27877812.

. PMID 27877812. - ↑ Waugh, Mark D (2010). "Design solutions for DC bias in multilayer ceramic capacitors" (PDF). Electronic Engineering Times.

- ↑ von Hippel, A. (1950-07-01). "Ferroelectricity, Domain Structure, and Phase Transitions of Barium Titanate". Reviews of Modern Physics. 22 (3): 221–237. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.22.221.

- ↑ Shieh, J.; Yeh, J. H.; Shu, Y. C.; Yen, J. H. (2009-04-15). "Hysteresis behaviors of barium titanate single crystals based on the operation of multiple 90° switching systems". Materials Science and Engineering: B. Proceedings of the joint meeting of the 2nd International Conference on the Science and Technology for Advanced Ceramics (STAC-II) and the 1st International Conference on the Science and Technology of Solid Surfaces and Interfaces (STSI-I). 161 (1–3): 50–54. doi:10.1016/j.mseb.2008.11.046. ISSN 0921-5107. Retrieved 2015-11-05.

- ↑ Godefroy, Geneviève (1996). "Ferroélectricité". Techniques de l'ingénieur Matériaux pour l'électronique et dispositifs associés (in French). base documentaire : TIB271DUO. (ref. article : e1870).

- ↑ "Fe:LiNbO3 Crystal". redoptronics.com.

- ↑ Tang, Pingsheng; Towner, D.; Hamano, T.; Meier, A.; Wessels, B. (2004). "Electrooptic modulation up to 40 GHz in a barium titanate thin film waveguide modulator". Optics Express. 12 (24): 5962–7. doi:10.1364/OPEX.12.005962. PMID 19488237.

- ↑ "Nanoparticle Compatibility: New Nanocomposite Processing Technique Creates More Powerful Capacitors". gatech.edu. April 26, 2007. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ↑ Ma, Chi; Rossman, George R. (2008). "Barioperovskite, BaTiO3, a new mineral from the Benitoite Mine, California". American Mineralogist. 93: 154–157. doi:10.2138/am.2008.2636.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Barium titanate. |

- Nanoparticle Compatibility: New Nanocomposite Processing Technique Creates More Powerful Capacitors

- EEStor's "instant-charge" capacitor batteries