Aysheaia

| Aysheaia Temporal range: Middle Cambrian | |

|---|---|

| |

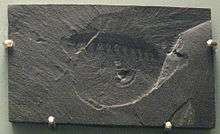

| Aysheaeia, type specimen, retouched image from Walcott 1911. | |

| |

| Reconstruction of A. pedunculata | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Lobopodia |

| Class: | Xenusia |

| Family: | Aysheaiidae |

| Genus: | Aysheaia |

| Type species | |

| Aysheaia pedunculata Walcott 1911 | |

| Species | |

| |

Aysheaia was a genus of Cambrian-aged soft-bodied, caterpillar-shaped fossil organisms with average body lengths of 1–6 cm.

Anatomy

Aysheaia has ten body segments, each of which has a pair of spiked, annulated legs. The animal is segmented, and looks somewhat like a bloated caterpillar with a few spines added on — including six finger-like projections around the mouth and two grasping legs on the "head." Each leg has a subterminal row of about six curved claws.[1] No jaw apparatus is evident.[2] A pair of legs marks the posterior end of the body, unlike in onychophorans where the anus projects posteriad; this may be an adaptation to the terrestrial habit.[2]

Ecology

Based on its association with sponge remains, it is believed that Aysheaia was a sponge grazer and may have protected itself from predators by seeking refuge within sponge colonies. Aysheaia probably used its claws to cling to sponges.

A terminal mouth is also seen in tardigrades that are omnivores or predators (but not detritovores or algavores) — this may provide an ecological signal.[2]

Affinity

Unlike many early Cambrian forms whose relationships are obscure and puzzling, Aysheaia is remarkably similar to a modern phylum, the Onychophora (velvet worms). Notable differences are the lack of jaws and antennae, and the terminal mouth.[2]

Distribution

Species of Aysheaia are known from fossils found in the middle Cambrian Burgess shale of British Columbia, and from the Wheeler Formation in Utah.[2] Similar taxa are known from the lower Cambrian Maotianshan shales of China. Other than the 20 specimens from the Greater Phyllopod bed, where they comprise 2% of the community,[3] only 19 specimens of A. pedunculata are known. A. prolata is the species from the similarly-aged Wheeler Shale Formation of Utah.

History of research

Description by Walcott (1911)

Aysheaia was described by Walcott in his 1911 work on annelid worms; Walcott imagined a that head (not observed) was present to support a polychaete affinity.[1] His attention was soon drawn to its resemblance to velvet worms (Onychophora),[1] which was formally mooted by other early workers (1920s-30s) who recognized a similarity with the onychophora,[4] although because it does not fall within the range of living onychophora, it has also been allocated to a phylum of its own.[5] Nevertheless, an Onychophoran affinity represented the common opinion until the fossil was redescribed in the late 1970s.[2]

Major redescription by Whittington, 1978

In the 1970s, Whittington undertook a thorough redescription,[1] and entertained as the tardigrade affinity picked up a couple of years earlier by Delle Cave and Simonetta,[6] and first proposed in 1958.[7] In modern parlance, his interpretation places Aysheaia in the stem group to Tardigrada + Onychophora, although the view at the time was that these two modern phyla represented a group within a polyphyletic Arthropoda.[1] A possible link to Xenusion was also proposed, although at this time the affinities of this group were unclear, and a link to the rangeomorphs had been proposed![1]

Response to Whittington (1980s)

The response to Whittington's redescription can be loosely classed into three camps: one school, predominantly Bergström, downplayed the similarities to the Onychophora and focussed on the Tardigrade interpretation; whereas others (after Simonetta and Delle Cave) recognized a group of lobopods containing Onychophora, Tardigrada, and Aysheaia (with features of both).[2] Robison preferred to interpret Onychophora as the sister group to Arthropoda, and placed Aysheaia in the Onychophoran stem group in a taxon called Protonychophora (solely containing Aysheaia). These were differentiated from Euonychophora (the crown group) by the number of lobopod legs and claws, the unusual head appendages, the absence of eyes, jaws, antennae and slime glands, the morphology of the rear of the body, and the terminal mouth.[2]

Modern era

Later work uncovered further material of Xenusion and relatives, particularly from the Chinese fossil deposits. In light of the cladistic revolution of the 1990s, Aysheaia and its relatives were recognized as early offshoots of the lineage leading to arthropods and onychophorans.

Looking from the opposite direction, Budd points out that there are no characters that exclude Aysheaia from the Arthropoda.[8] It may be premature to assign Aysheaia to the onychophora over Arthropoda, as it lacks any distinctive features of the onychophoran crown group; rather, both Onychophora and Arthropoda may have arisen from animals resembling Aysheaia and its kin.[9] Budd sees Aysheaia-like organisms as representing a paraphyletic grade from which both modern onychophoran and arthropods evolved.[8][10]

Etymology

The genus name commemorates a mountain peak named "Ayesha" due north of the Wapta Glacier. This peak was originally named Aysha in the 1904 maps of the region, and was renamed Ayesha after the heroine of Rider Haggard's 1887 novel She.[11]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Whittington, H. B. (16 November 1978). "The Lobopod animal Aysheaia pedunculata Walcott, Middle Cambrian, Burgess Shale, British Columbia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B, Biological Sciences. 284 (1000): 165–197. Bibcode:1978RSPTB.284..165W. doi:10.1098/rstb.1978.0061. JSTOR 2418243.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Robison, R. A. (1985). "Affinities of Aysheaia (Onychophora), with Description of a New Cambrian Species". Journal of Paleontology. Paleontological Society. 59 (1): 226–235. JSTOR 1304837.

- ↑ Caron, Jean-Bernard; Jackson, Donald A. (October 2006). "Taphonomy of the Greater Phyllopod Bed community, Burgess Shale". PALAIOS. 21 (5): 451–65. doi:10.2110/palo.2003.P05-070R. JSTOR 20173022.

- ↑

- BRUES, C. T. 1923. The geographical distribution of the Onychophora. American Naturalist, 57: 210-217.

- WALTON, L. B. 1927. The polychaete ancestry of the insects. American Naturalist, 61: 226-250.

- HUTCHINSON, G. E. 1930. Restudy of some Burgess Shale fossils. Proceedings of the United States National Museum, 78(11): 59.

- WALCOTT, C. D. 1931. Addenda to descriptions of Burgess Shale fossils. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 85(3): 1-46.

- ↑ Tiegs, O. W.; Manton, S. M. (1958). "The Evolution of the Arthropoda". Biological Reviews. 33 (3): 255. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1958.tb01258.x.

- ↑ DELLE CAVE, L. AND A. M. SIMONETTA. 1975. Notes on the morphology and taxonomic position of Aysheaia (Onycophora?) and of Skania (undetermined phylum). Monitore Zoologico Italiano, 9: 67-81.

- ↑ TIEGS, O. W. AND S. M. MANTON. 1958. The evolution of the Arthropoda. Biological Reviews, 33(3): 255-333.

- 1 2 Budd, G. (2001). "Tardigrades as 'Stem-Group Arthropods': The Evidence from the Cambrian Fauna". Zoologischer Anzeiger. 240 (3–4): 265–279. doi:10.1078/0044-5231-00034. ISSN 0044-5231.

- ↑ Budd, G. E.; Telford, M. J. (2009). "The origin and evolution of arthropods". Nature. 457 (7231): 812–817. Bibcode:2009Natur.457..812B. doi:10.1038/nature07890. PMID 19212398.

- ↑ Budd, G. E. (2001). "Why are arthropods segmented?". Evolution and Development. 3 (5): 332–42. doi:10.1046/j.1525-142X.2001.01041.x. PMID 11710765.

- ↑ "Ayesha Peak". British Columbia Geographical Names Information System. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

External links

"Aysheaia pedunculata". Burgess Shale Fossil Gallery. Virtual Museum of Canada. 2011.

Further reading

- Whittington, H. B. (16 November 1978). "The Lobopod animal Aysheaia pedunculata Walcott, Middle Cambrian, Burgess Shale, British Columbia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B, Biological Sciences. 284 (1000): 165–197. Bibcode:1978RSPTB.284..165W. doi:10.1098/rstb.1978.0061. JSTOR 2418243.

- Robison, R. A. (1985). "Affinities of Aysheaia (Onychophora), with Description of a New Cambrian Species". Journal of Paleontology. Paleontological Society. 59 (1): 226–235. JSTOR 1304837.