Assiniboine

|

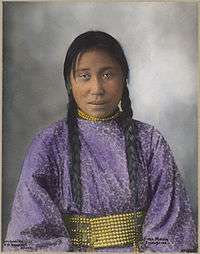

Full Moon, an Assiniboine woman, 1900 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (3,500[1]) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| Languages | |

| Assiniboine, English | |

| Religion | |

|

traditional tribal religion, Sun Dance, Native American Church, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Dakota, Stoney[1] |

The Assiniboine or Assiniboin people (/əˈsɪnᵻbɔɪn/ when singular, /əˈsɪnᵻbɔɪnz/ when plural; Ojibwe: Asinaan, "stone Sioux"; also in plural Assiniboine or Assiniboin), also known as the Hohe and known by the endonym Nakota (or Nakoda or Nakona), are a First Nations/Native American people originally from the Northern Great Plains of North America.

Today, they are centered in present-day Saskatchewan. They have also populated parts of Alberta and southwestern Manitoba in Canada, and northern Montana and western North Dakota in the United States. They were well known throughout much of the late 18th and early 19th century, and were members of the Iron Confederacy with the Cree. Images of Assiniboine people were painted by such 19th-century artists as Karl Bodmer and George Catlin.

Names

The Europeans and Americans adopted names that other tribes used for the Assiniboine; they did not until later learn the tribe's autonym, their name for themselves. In Siouan, they traditionally called themselves the Hohe Nakota. With the widespread adoption of English, however, many now use the name that became common in English. The English adopted Assiniboine, used by the Canadian French colonists. It was a transliteration into French phonetics of what they heard the Ojibwe use as a term for these western people. The Ojibwe name was asinii-bwaan (stone Sioux). The Cree called them asinîpwâta (asinîpwâta ᐊᓯᓃᐹᐧᑕ NA sg, asinîpwâtak ᐊᓯᓃᐹᐧᑕᐠ NA pl).

In the same way, Assnipwan comes from the word asinîpwâta in the western Cree dialects, from asiniy ᐊᓯᓂᐩ NA – "rock, stone" – and pwâta ᐹᐧᑕ NA – "enemy, Sioux". Early French traders in the west were often familiar with Algonquian languages. They transliterated many Cree or Ojibwe exonyms for other western Canadian indigenous peoples during the early colonial era. The English referred to the Assiniboine by adopting terms from the French spelled using English phonetics.

Other tribes associated "stone" with the Assiniboine because they primarily cooked with heated stones. They dropped hot stones into water to heat it to boiling for cooking meat. Some writers believed that the name was derived from the Ojibway term Assin, stone, and the French bouillir, to boil, but such an etymology is very unlikely.[2]

Language

Assiniboine is a Mississippi Valley Siouan language, in the Western Siouan language family. it is known as A' M̆oqazh. In the early 21st century, about 150 people speak the language[1] and most are more than 40 years old. The majority of the Assiniboine today speak only American English. The 2000 census showed 3,946 tribal members who lived in the United States.

Assiniboine are closely linked by language to the Stoney First Nations people of Alberta. The latter two tribes speak varieties of Nakota, a distant, but not mutually intelligible, variant of the Sioux language.[3]

Related peoples

The Assiniboine have many similarities to the Lakota Sioux in culture and language. They are considered to have separated from the central sub-group of the Sioux nation. Scholars believe that the Assiniboine broke away from Yanktonai Dakota in the 16th century.[4]

The Assiniboine were close allies and trading partners of the Cree, engaging in wars together against the Atsina (Gros Ventre). Together they later fought the Blackfoot. A Great Plains people, they generally went no further north than the North Saskatchewan River. They purchased a great deal of European trade goods from the Hudson's Bay Company through Cree middlemen.

History

Early history

The Assiniboine were originally part of the Great Sioux Nation which was made up of Eastern Dakota or Santee, Western Dakota or Yanktonai, and the Lakota or Teton Sioux. The Sioux were pushed gradually westward onto the plains from the woodlands of Minnesota by the Ojibwe people who acquired guns earlier from their French allies. Specifically the Assiniboine were part of the Yanktonai Sioux but split off around 1640 and headed north, where they developed into a powerful and distinct people. Before horses were introduced to the Assiniboine, they used domestic dogs as a pack animal to carry their belongings and pull their travois. The Assiniboine acquired horses by raiding and trading with neighboring plains nations such as the Crow and Sioux living further south, who obtained horses earlier.

The Assiniboine eventually developed into a large and powerful people with a horse and warrior culture; they used the horse to hunt the vast numbers of bison that lived within and outside their territory. At the height of their power, the Assiniboine dominated territory ranging from the North Saskatchewan River in the north to the Missouri River in the south, and including portions of modern-day Saskatchewan, Alberta, and Manitoba, Canada; and North Dakota and Montana, United States of America.

Contact with Europeans & fur trade

The first person of European descent to describe the Assiniboine was an employee of the Hudson's Bay Company named Henry Kelsey in the 1690s. Later explorers and traders Jean Baptiste de La Vérendrye and his sons (1730s), Anthony Henday (1754–55), and Alexander Henry the younger (1800s) confirmed that the Assiniboine held a vast territory across the northern plains, including into the United States (which achieved independence in 1783 but did not acquire the plains until 1803 in the Louisiana Purchase from France.)

The Assiniboine became reliable and important trading partners and middlemen for fur traders and other Indians, particularly the British Hudson's Bay Company and North West Company, operating in western Canada in a vast area known then as Rupert's Land. During the later 18th century and early 19th century, south of the border in what became Montana and the Dakota territories, the Assiniboine traded with the American Fur Company and the competing Rocky Mountain Fur Company. The Assiniboine obtained guns, ammunition, metal tomahawks, metal pots, wool blankets, wool coats, wool leggings, and glass beads, as well as other goods from the fur traders in exchange for furs. Beaver furs and bison hides were the most commonly traded furs.

Increased contact with Europeans resulted in Native Americans contracting Eurasian infectious diseases that were endemic among the Europeans. They suffered epidemics with high mortality, most notably smallpox among the Assiniboine. The Assiniboine population crashed from around 10,000 people in the late 18th century to around 2600 by 1890.[5]

The Lewis and Clark Expedition was mounted by the United States in 1804-1806 to explore the Louisiana Territory, newly acquired from France. The expedition's journals mention the Assiniboine, whom the party heard about while returning from Fort Clatsop down the Missouri River. These explorers did not encounter or come in direct contact with the tribe.

Noted European and American painters traveled with traders, explorers, and expeditions for the opportunity to paint the West and its Native American peoples. Among those who encountered and painted the Assiniboine from life were painters Karl Bodmer, Paul Kane, and George Catlin.

The Iron Confederacy

The Assiniboine were a major part of an alliance of northern Plains Indian nations known as the Iron Confederacy, or Nehiyaw-Pwat, as it is known in Plains Cree. The Iron Confederacy were allies in the fur trade, particularly with the Hudson's Bay Company. Members included the Assiniboine as well as the Plains Cree, Saulteaux, Plains Ojibwe, Métis, and individual Iroquois people who traveled west as employees for the fur traders. Other Indian peoples on the northern plains, such as the Gros Ventre, were occasionally part of the confederacy.

The confederacy became the dominant force on the northern plains. It posed a major threat to Indian nations not associated with it, such as the Shoshone and Crow further south. Its members also attacked European-American settlements on the Plains. The eventual decline of the fur trade and overhunting of the bison herds by Canadian and American hunters, which destroyed the Confederacy nations' most important food source, led to the defeat and breaking up of the confederacy. It engaged in military action with Canada during the North-West Rebellion.[6]

Lifestyle

Traditionally the Assiniboine were semi-nomadic people. During the warmer months, they followed and hunted the herds of bison. The women processed and preserved the meat for winter, and used hides, tendons, and horns for clothing, bedding, tools, cord and other items. Every part of the animal was used by the people. The men hunted on horseback using bow and arrows. The tribe is known for its excellent horsemanship. They first obtained horses by trading with the Blackfeet and the Gros Ventre tribes. They worked with the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara tribes.

Subgroups and bands

- Aegitina (‘Camp Moves to the Kill’)

- Bizebina, Bízebina (‘Gophers’ or 'Gopher People')[7]

- Cepahubi (‘Large Organs’)

- Canhdada, Cąȟtáda (‘Moldy People’, lived around Battleford (Ogíciza Wakpá) and North Battleford - known as "The Battlefords" - as neighbors of the Waziyamwincasta Band; political once part of the Upstream People of Plains Cree - today known as Battleford Stoneys part of the Mosquito, Grizzly Bear's Head, Lean Man First Nations)

- Canhewincasta, Cą́ȟe wįcášta, Chan He Winchasta (‘Wooded-Mountain People’ or ‘Wood Mountain People’ – ‘People Who live around Wood Mountain’, lived around today's Wood Mountain and in the adjoining Big Muddy Badlands to the southeast in southern Saskatchewan and northern Montana; close allies to the Insaombi (Cypress Hills Assiniboine) band,' in which territory they had their winter camps. They were once politically part of the "Downstream People" of Plains Cree and close allies of the Cree-Assiniboine / Young Dogs; today they are part of the Carry the Kettle Nakoda First Nation.

The bands of chief Manitupotis (also known as Wankanto - Little Soldier) and Hunkajuka (Hum-ja-jin-sin, Inihan Kinyen - Little Chief), together about 300 people with about 50 warriors, on June 1, 1873 were victims of the Cypress Hills Massacre. An estimated 25 to 30 Assiniboine were killed by American Wolfers to take revenge for horse-stealing Cree in Montana. This massacre led to the development of the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP), later known as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP).

- Canknuhabi (‘Ones That Carry Their Wood’), Cątų́wąbi (‘Forest Villagers, Wood Villagers’)

- Hudesabina, Húdešana, Hudesanak (‘Red Bottom’ or ‘Red Root’, split off from the Wadopabina Band in 1844, lived between the Porcupine Creek and Milk River (Asą́bi wakpá, Wakpá jukʾána) area in northern Montana and southern Alberta, Canada. Today they are an Assiniboine / Nakoda band of the federally recognized Fort Peck Assiniboine & Sioux Tribes.

- Hebina, Ye Xa Yabine (‘Rock Mountain People’, often called Strong Wood Assiniboine or Thickwood Assiniboine, separated from the main body of the Assiniboine in the mid-18th century and moved further west and northwest deep into the forests and Rocky Mountains (In-yan-he-Tonga, į́yąȟetąga – ′great mountains′) to escape smallpox. Because they stayed isolated, they developed a separate identity as Mountain Stoney-Nakoda. Today they are part of the Stoney Nakoda First Nation (Wesley First Nation, Chiniki First Nation, Bearspaw First Nation); some also reside together with other Assiniboine / Nakoda bands in the federally recognized Fort Belknap Indian Community. Some are part of the Aseniwuche Winewak Nation from Canada, which is not recognized by the government as a band.

- Hen atonwaabina (‘Little Rock Mountain People’, lived in the Little Rocky Mountains (or Little Rockies, į́yąȟe widána, į́yąȟewida; today: į́yąȟejusina) and the adjoining Plains in the Northeast of Montana; once political part of the Downstream People of Plains Cree and close allies of the Cree-Assiniboine / Young Dogs - today part of the Fort Belknap Indian Community)

- Huhumasmibi, Huhumasmlbi (‘Bone Cleaners’)

- Huhuganebabi (‘Bone Chippers’)

- Indogahwincasta (‘East People’)

- Inninaonbi, Ini'na u'mbi (‘Quiet People’)

- Insaombi, įšná ųbísʾa, Icna'umbisa (‘The Ones Who Stay Alone’, lived in Cypress Hills and adjoining Plains in southern Saskatchewan, Canada; they were also known as the Cypress Hills Assiniboine. They were close allies of the Canhewincasta band, which often wintered in the Cypress Hills. Today they are part of Carry the Kettle Nakoda First Nation.[8]

- Inyantonwanbina, Iyethkabi, Îyârhe Nakodabi, auch Mountain Village Band (‘Stone / Rock People’, ‘Mountain People.’ At the end of the 18th century they had retreated deep into the Rocky Mountains (In-yan-he-Tonga, į́yąȟetąga – ′great mountains′) and developed a separate identity as Nakoda (Stoney) (į́yąȟe wįcášta). Today they are one Assiniboine / Nakoda band of the federally recognized Fort Peck Assiniboine & Sioux Tribes.

- Minisose Swnkeebi, Miníšoše Sunkcebi (‘Missouri River Dog Band’, lived between the Milk River and the Poplar River toward the Missouri River (Miníšoše) in the border region of Montana, Alberta and Saskatchewan. Today they are one Assiniboine / Nakoda band of the federally recognized Fort Peck Assiniboine & Sioux Tribes.

- Minisatonwanbi, Miníšatonwanbi (‘Red Water People’), lived along the Red River of the North in the vicinity of today's Winnipeg toward the south banks of Lake Winnipeg and Lake Manitoba in southern Manitoba

- Osnibi, Osníbina (‘People of the Cold’, one band of Woodland Assiniboine from the North, where the weather is cold.

- Ptegabina, Psamnéwi, PwSymAWock (‘Swamp People’)

- Sahiyaiyeskabi, šahíya iyéskabina (‘Plains Cree-Speakers’, also known as Cree-Assiniboine / Young Dogs, built up from a number of bands of Plains Cree and Assiniboine. They were later joined by Plains Ojibwe (Salteaux). They had in common living and traveling in ethnically mixed bands and camps; they had switched to speaking Plains Cree instead of their former mother tongue. They were politically part of the Cree-Assiniboine / Young Dogs, part of the Downstream People of Plains Cree. Today they are part of Little Black Bear First Nation, Piapot First Nation in Canada, and of the federally recognized Landless Cree of the Fort Peck Assiniboine & Sioux Tribes and Landless Cree and Rocky Boy Cree of the Fort Belknap Indian Community in the United States. They identify today as Cree.

- Sihabi, Sihábi (‘Foot People’, also known as Foot Assiniboine, developed a separate identity as Wood Stoney-Nakoda - some as Mountain Stoney-Nakoda; as Wood Stoney-Nakoda once political part of the Beaver Hills Cree of the Upstream People of Plains Cree. Today they are known as the Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation and Paul First Nation. As Mountain Stoney-Nakoda, they were part of the Rocky / Mountain Cree of Plains Cree. Today this is Wesley First Nation under Stoney Nakoda First Nation.

- Snugabi (‘Contrary People’)

- Sunkcebi, šųkcébina (‘Dog Band’, ‘Dog Penis Band’; once political part of the Calling River / Qu'Appelle Cree of Plains Cree. Today they are part of White Bear First Nation; some are part of Carry the Kettle Nakoda First Nation)

- Tanidabi, Tanį́debina, Tanin'tabin (‘Buffalo Hip’)

- Tokanbi, Toką́kna, Tokaribi (‘Strangers’)

- Tanzinapebina, Taminapebina (‘Owners of Sharp Knives’)

- Unskaha (‘Roamers’)

- Wadopabina, Wadópana (‘Canoe Paddlers’), the Cree called them Pimiskau Wi Iniwak - ‘paddling Assiniboines’, therefore in English often called Canoe Assiniboine, Paddling Assiniboine. Today one Assiniboine / Nakoda band of the Fort Peck Assiniboine & Sioux Tribes)

- Wadopahnatonwan, Wadópaȟna Tųwą, Wado Pahanda Tonwan (‘Canoe Paddlers Who Live on the Prairie’, split from the Wadopabina band to roam the plains, the European traders called them Watopachnato - Big Devils, because they were known as cunning traders and great warriors and horse thieves; today one Assiniboine / Nakoda band of the Fort Peck Assiniboine & Sioux Tribes and Fort Belknap Indian Community)

- Waką́hežabina, in English often called Little Girls Band and by the French as Gens des Feuilles; today one Assiniboine / Nakoda band of the Fort Peck Assiniboine & Sioux Tribes)

- Wasinazinyabi, Waci'azi hyabin (‘Fat Smokers’)

- Waziyamwincasta, Wazíyam Wįcášta, Waziya Winchasta, Wiyóhąbąm Nakóda (‘People of the North’; once political part of the Parklands Cree of the Upstream People of Plains Cree - today living on Indian reserve Mosquito#109 and known as Battleford Stoneys they are part of the Mosquito, Grizzly Bear's Head, Lean Man First Nations, some of them moved about 1839 into the United States and are today part of Nakoda / Assiniboine bands of the Fort Belknap Indian Community)

- Wiciyabina, Wichiyabina (‘Ones That Go to the Dance’, therefore often called for short Wįcį́jana - Girl Band; political once part of the Calling River / Qu'Appelle Cree of the Downstream People of Plains Cree - today one Assiniboine / Nakoda band of the Fort Peck Assiniboine & Sioux Tribes)

- Wokpanbi, Wókpąnbi (‘Meat Bag’)[9]

Present situation

Today, a substantial number of Assiniboine people live jointly with other tribes, such as the Plains Cree, Saulteaux, Sioux and Gros Ventre, in several reservations in Canada and the United States. In Manitoba, the Assiniboine survive as individuals, holding no separate communal reserves.

Montana, United States

- Fort Peck (about 11,786 Hudesabina, Wadopabina, Wadopahnatonwan, Sahiyaiyeskabi, Inyantonwanbina and Fat Horse Band of the Assiniboine,[10] Sisseton, Wahpeton, Yanktonai and Hunkpapa of the Sioux live together on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation near Fort Peck in NE Montana north of the Missouri River, ca. 8,518 km², Tribal Headquarters are located in Poplar, largest community on the reservation is the city of Wolf Point)[11]

- Fort Belknap (of about 5,426 enrolled Assiniboine and Gros Ventre). The majority of the people live on the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation; some 505 live elsewhere. It is in north central Montana, and largest city is Fort Belknap Agency, ca. 2,626 km²)[12]

In March 2012, these two reservations has received 63 American bison from Yellowstone National Park, to be released to a 2,100-acre game preserve 25 miles north of Poplar. There are many other bison herds outside Yellowstone, this is one of the few genetically pure ones, in which the animals were not cross-bred with cattle. Native Americans celebrated this action for restoration of the bison. It came more than a century after the bison were nearly destroyed by overhunting by European Americans and government action to destroy the food source of the powerful Plains Indians. The Assiniboine and Gros Ventre tribes at the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation will also receive a portion of this herd. [13]

Saskatchewan, Canada

- Carry the Kettle Nakoda First Nation (the reserve Carry the Kettle Nakoda First Nation #76, also known as: 'Assiniboine #76', or Carry the Kettle #76-18,19,22, Treaty Four Reserve Grounds #77, includes ca. 350 km², in SE Saskatchewan, 80 km east of Regina and 18 km south of Sintaluta, of 2,387 registered Assiniboine only about 850 live on the reserve)[14]

- Mosquito, Grizzly Bear's Head, Lean Man First Nations (also known as Battleford Stoneys) (includes the following reserves: Mosquito #109, Cold Eagle, Grizzly Bear`s Head #110 & Lean Man #111, Mosquito Grizzly Bear`s Head Lean Man Tle #1, Tribal Headquarters and Administration are 27 km south of Battleford, ca. 127 km², in 2003 there were about 1,119 registered Assiniboine)[15]

- White Bear First Nation (reserves: White Bear #70 and Treaty Four Reserve Grounds #77 are located in SE corner of the Moose Mountain area of Saskatchewan, Tribal Headquarters are located 13 km north of Carlyle, ca. 172 km², about 1,990 Assiniboine, Saulteaux (Anishinaabe), Cree and Dakota)[16]

- Ocean Man First Nation (reserves: Ocean Man #69, 69A-I, Treaty Four Reserve Grounds #77, Tribal Headquarters are located 19 km north of Stoughton, ca. 41 km², of 454 registered Assiniboine, Cree and Saulteaux (Anishinaabe) only 170 are living on reserve grounds)[17]

- Pheasant Rump Nakota First Nation (reserve: Treaty Four Reserve Grounds #77, Tribal Headquarters are located in Kisbey, about 333 Assiniboine, Saulteaux (Anishinaabe) and Cree)[18]

Namesakes

Canada Steamship Lines named one of their new ships the CSL Assiniboine.[19]

Fort Assiniboine was a name given to a trading post opened in 1793 in Manitoba and in 1824 in Alberta

The Assiniboine River drains much of Saskatchewan and Manitoba into the Red River of the North, which, in turn, flows into the Hudson Bay via Lake Winnipeg and the Nelson River.

Gallery

-

Two young Assiniboine boys.

-

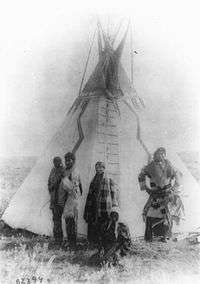

A skin lodge of an Assiniboine chief.

-

Tomb platforms of Assiniboine in trees.

-

Assiniboine in Montana, 1890–1891.

-

An Assiniboine man named Cloud Man.

-

Assiniboine baby carrier.

-

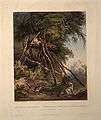

Two Assiniboine warriors, painted by Karl Bodmer.

Notable Assiniboine people

- Hank Adams (b. 1943), indigenous rights activist

- Dolly Akers, Montana legislator

- Crazy Bear (Mah-To-Wit-Ko), 1785–1856), chief and negotiator

- Juanita Growing Thunder Fogarty (b. 1969), bead artist, quillworker, and regalia maker

- Roxy Gordon (1945–2000), poet, novelist, musician and activist

- Indigenous, Nakota blues band

- Georgia Wettlin Larsen, singer

- Wi-jún-jon (1796–1872), chief

- William S. Yellow Robe, Jr. (b. 1950), playwright, author, poet

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Assiniboine. |

References

- 1 2 3 "Assiniboine." Ethnologue. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ↑ George Bryce, The Assiniboine River and its Forts, Trans. Roy. Soc. Canada, 1893, Section II, p. 69

- ↑ Ullrich, Jan (2008). New Lakota Dictionary (Incorporating the Dakota Dialects of Yankton-Yanktonai and Santee-Sisseton). Lakota Language Consortium. pp. 2–6. ISBN 0-9761082-9-1.

- ↑ for a report on the long-established blunder of misnaming “Nakota” the Yanktonai people, see the article Nakota

- ↑ "Assiniboine". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2013-05-28.

- ↑ Neal McLeod. "Cree". The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. Canadian Plains Research Centre. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ↑ Hochspringen ↑ AISRI Dictionary Database Search - Assiniboine Dictionary

- ↑ POLITICAL STRUCTURE AND STATUS AMONG THE ASSINIBOINE INDIANS

- ↑ James L. Long, William Standing: Land of Nakoda: The Story of the Assiniboine Indians, Riverbend Publishing 2004, ISBN 978-1-931832-35-9

- ↑ History of the Fort Peck Reservation Archived October 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Fort Peck Tribes

- ↑ Fort Belknap Indian Community Archived October 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Yellowstone bison return to tribal land". Great Falls Tribune. 2012-03-21. Retrieved 2012-03-23.

- ↑ Carry the Kettle First Nation

- ↑ FIRST NATION CONNECTIVITY PROFILE – 2003 Archived April 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ White Bear First Nation

- ↑ Ocean Man First Nation Archived April 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Pheasant Rump Nakota Nation Archived July 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Great Lakes and Seaway Shipping (2005). "CSL Assiniboine". Retrieved 2007-05-02.

Further reading

- Denig, Edwin Thompson, and J. N. B. Hewitt. The Assiniboine. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8061-3235-3

- Fort Belknap Curriculum Development Project. Assiniboine Memories Legends of the Nakota People. Harlem, Mont: Fort Belknap Education Dept, 1983.

- How the Summer Season Came And Other Assiniboine Indian Stories. Helena, Mont: Montana Historical Society Press, with the Fort Peck and Fort Belknap Tribes, 2003. ISBN 0-917298-94-2

- Kennedy, Dan, and James R. Stevens. Recollections of an Assiniboine Chief. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1972. ISBN 0-7710-4510-7

- Nighttraveller, Will, and Gerald Desnomie. Assiniboine Legends, Saskatoon: Saskatchewan Indian Cultural College, 1973.

- Nighttraveller, Will, and Gerald Desnomie. Assiniboine Legends, Saskatoon: Saskatchewan Indian Cultural College, 1973.

- Schilz, Thomas F. 1984. "Brandy and Beaver Pelts Assiniboine-European Trading Patterns, 1695–1805". Saskatchewan History. 37, no. 3.

- Writers' Program (Mont.), James Larpenteur Long, and Michael Stephen Kennedy. The Assiniboines From the Accounts of the Old Ones Told to First Boy (James Larpenter Long), The Civilization of the American Indian series. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961.

External links

- Lewis & Clark Corps of Discovery encounters with Assiniboine

- "Assiniboine", Minnesota State University, Mankato emuseum

- Assiniboine Community College

- Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux History, University of Montana